Working Paper Number 155 the Indian State in a Liberalising

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BHUJ "Ancient Temples, Tall Hills and a Deep Sense of Serenity" Bhuj Tourism

BHUJ "Ancient temples, tall hills and a deep sense of serenity" Bhuj Tourism A desert city with long history of kings and empires make Bhuj one of the most interesting and unique historical places to see. The city has a long history of kings and empires - and hence many historic places to see. The city was left in a state of devastation after the 2001 earthquake and is still in the recovery phase. Bhuj connects you to a range of civilizations and important events in South Asian history through prehistoric archaeological finds, remnants of the Indus Valley Civilization (Harappan), places associated with the Mahabharata and Alexander the Great's march into India and tombs, palaces and other buildings from the rule of the Naga chiefs, the Jadeja Rajputs, the Gujarat Sultans and the British Raj. The vibrant and dynamic history of the area gives the area a blend of ethnic cultures. In a walk around Bhuj, you can see the Hall of Mirrors at the Aina Mahal; climb the bell tower of the Prag Mahal next door; stroll through the produce market; have a famous Kutchi pau bhaji for lunch; examine the 2000-year-old Kshatrapa inscriptions in the Kutch Museum; admire the sculptures of Ramayana characters at the Ramakund stepwell; walk around Hamirsar Lake and watch children jumping into it from the lake walls as the hot afternoon sun subsides; and catch the sunset among the chhatardis of the Kutchi royal family in a peaceful field outside the center of town. This Guide includes : About Bhuj | Suggested Itinerary | Commuting tips | Top places to visit | Hotels | Restaurants | Related Stories Commuting in Bhuj Tuk-tuks (autorickshaws) are the best way to travel within the city. -

The Migration of Indians to Eastern Africa: a Case Study of the Ismaili Community, 1866-1966

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2019 The Migration of Indians to Eastern Africa: A Case Study of the Ismaili Community, 1866-1966 Azizeddin Tejpar University of Central Florida Part of the African History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Tejpar, Azizeddin, "The Migration of Indians to Eastern Africa: A Case Study of the Ismaili Community, 1866-1966" (2019). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 6324. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/6324 THE MIGRATION OF INDIANS TO EASTERN AFRICA: A CASE STUDY OF THE ISMAILI COMMUNITY, 1866-1966 by AZIZEDDIN TEJPAR B.A. Binghamton University 1971 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Spring Term 2019 Major Professor: Yovanna Pineda © 2019 Azizeddin Tejpar ii ABSTRACT Much of the Ismaili settlement in Eastern Africa, together with several other immigrant communities of Indian origin, took place in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth centuries. This thesis argues that the primary mover of the migration were the edicts, or Farmans, of the Ismaili spiritual leader. They were instrumental in motivating Ismailis to go to East Africa. -

Important Lakes in India

Important Lakes in India Andhra Pradesh Jammu and Kashmir Kolleru Lake Dal Lake Pulicat Lake - The second largest Manasbal Lake brackish – water lake or lagoon in India Mansar Lake Pangong Tso Assam Sheshnag Lake Chandubi Lake Tso Moriri Deepor Beel Wular Lake Haflong Lake Anchar Lake Son Beel Karnataka Bihar Bellandur Lake Kanwar Lake - Asia's largest freshwater Ulsoor lake oxbow lake Pampa Sarovar Karanji Lake Chandigarh Kerala Sukhna Lake Ashtamudi Lake Gujarat Kuttanad Lake Vellayani Lake Hamirsar Lake Vembanad Kayal - Longest Lake in India Kankaria Sasthamcotta Lake Nal Sarovar Narayan Sarovar Madhya Pradesh Thol Lake Vastrapur Lake Bhojtal Himachal Pradesh www.OnlineStudyPoints.comMaharashtra Brighu Lake Gorewada Lake Chandra Taal Khindsi Lake Dashair and Dhankar Lake Lonar Lake - Created by Metoer Impact Kareri and Kumarwah lake Meghalaya Khajjiar Lake Lama Dal and Chander Naun Umiam lake Macchial Lake Manipur Haryana Loktak lake Blue Bird Lake Brahma Sarovar Mizoram Tilyar Lake Palak dïl Karna Lake www.OnlineStudyPoints.com Odisha Naukuchiatal Chilika Lake - It is the largest coastal West Bengal lagoon in India and the second largest Sumendu lake in Mirik lagoon in the world. Kanjia Lake Anshupa Lake Rajasthan Dhebar Lake - Asia's second-largest artificial lake. Man Sagar Lake Nakki Lake Pushkar Lake Sambhar Salt Lake - India's largest inland salt lake. Lake Pichola Sikkim Gurudongmar Lake - One of the highest lakes in the world, located at an altitude of 17,800 ft (5,430 m). Khecheopalri Lake Lake Tsongmo Tso Lhamo Lake - 14th highest lake in the world, located at an altitude of 5,330 m (17,490 ft). -

Nesting in Paradise Bird Watching in Gujarat

Nesting in Paradise Bird Watching in Gujarat Tourism Corporation of Gujarat Limited Toll Free : 1800 200 5080 | www.gujarattourism.com Designed by Sobhagya Why is Gujarat such a haven for beautiful and rare birds? The secret is not hard to find when you look at the unrivalled diversity of eco- Merry systems the State possesses. There are the moist forested hills of the Dang District to the salt-encrusted plains of Kutch district. Deciduous forests like Gir National Park, and the vast grasslands of Kutch and Migration Bhavnagar districts, scrub-jungles, river-systems like the Narmada, Mahi, Sabarmati and Tapti, and a multitude of lakes and other wetlands. Not to mention a long coastline with two gulfs, many estuaries, beaches, mangrove forests, and offshore islands fringed by coral reefs. These dissimilar but bird-friendly ecosystems beckon both birds and bird watchers in abundance to Gujarat. Along with indigenous species, birds from as far away as Northern Europe migrate to Gujarat every year and make the wetlands and other suitable places their breeding ground. No wonder bird watchers of all kinds benefit from their visit to Gujarat's superb bird sanctuaries. Chhari Dhand Chhari Dhand Bhuj Chhari Dhand Conservation Reserve: The only Conservation Reserve in Gujarat, this wetland is known for variety of water birds Are you looking for some unique bird watching location? Come to Chhari Dhand wetland in Kutch District. This virgin wetland has a hill as its backdrop, making the setting soothingly picturesque. Thankfully, there is no hustle and bustle of tourists as only keen bird watchers and nature lovers come to Chhari Dhand. -

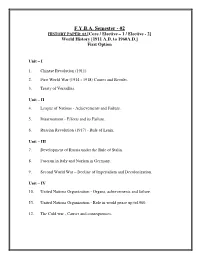

History Sem-2

F.Y.B.A. Semester - 02 HISTORY PAPER: 03 [Core / Elective – 1 / Elective - 2] World History [1911 A.D. to 1960A.D.] First Option Unit – I 1. Chinese Revolution (1911) 2. First World War (1914 - 1918) Causes and Results. 3. Treaty of Versailles. Unit – II 4. League of Nations - Achievements and Failure. 5. Disarmament - Efforts and its Failure. 6. Russian Revolution (1917) - Rule of Lenin. Unit – III 7. Development of Russia under the Rule of Stalin. 8. Fascism in Italy and Nazism in Germany. 9. Second World War – Decline of Imperialism and Decolonization. Unit – IV 10. United Nations Organization - Organs, achievements and failure. 11. United Nations Organization - Role in world peace up to1960. 12. The Cold war - Causes and consequences. REFERENCE BOOKS: 1. Revil, J.C . : World History (Longmans Green & Co. London,1962) 2. Weech, W.N. : History of the World (Asia publishing House, Bombay,1964) 3. Vairanapillai, M.S. : A Concise World History (Madura Book House,Madurai) 4. Sharma, S.R. : A Brief Survey of HumanHistory 5. Hayes, Moon & Way Land : World History (Mac Millan, New York,1957) 6. Thoms, David : World History (O.U.P. London,1956) 7. Langsam, W.C. : The World Since 1919 (Mac Millan, New York,1968) 8. Ketelby C.D.M. : A History of Modern Times from 1789 (George G. Harrap& Co. London,1966) 9. SF{X, o VFW]lGS lJ`JGM .lTCF; 10. l+5F9L4 ZFD5|;FN o lJ`J .lTCF; slCgNL ;lDlT4 ,BGF{f 11. XDF"4 ZFWFS'Q6 o N]lGIFGL SCFGL EFU !vZ 12. lJnF,\SFZ4 ;tIS[T] o I]ZM5GL VFW]lGS .lTCF; s;Z:JTL ;NG4 D{;]ZL !)*Zf 13. -

District Census Handbook, 7 Kutch

CENSUS 1961 GUJARAT DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK 7 KUTCH DISTRICT R. K. TRIVEDI Superinttndem oj Census Operations, Gujaraf PRICE Rs, 9.60 nP. DISTRICT: KUTCH , I- ~ !i; ts 0:: '( <.!> '( «2: ~ 2: UJ '":::> "' li ,_ I IJ IX I- J 15 i! l- i:! '-' ! iii tii i5 CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 LIST OF PUBLICATIONS CENTRAL GOVERNMENT PUBUCATIONS Census of India. 1961 Volume V-Gujarat is being published in the following parts: I-A General Report I-B Report on Vital Statistics and Fertility Survey I-C Subsidiary Tables II-A General Population Tables II-B(l) General Economic Tables (Tables B-1 to B-IV-C) I1-B(2) General Economic Tables (Tables B-V to B-IX) U-C Cultural and Migration Tables 111 Household Economic Tables (Tables B-X to B-XVII) IV-A Report on Housing and Establishments IV-B Housing and Establishment Tables V-A Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes V-B Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes and S~heduled Tribes (including reprints) VI Village Survey Monographs {25 Monogra~hsf i " VII-A Selected Crafts of Gujarat VII-B Fairs and Festivals VIII-A Admi nistra tion Report-EnumerationI Not for Sale VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation IX A tlas Volume X Special Report on Cities STATE GOVERNMENT PUBUCATIONS 17 District Census Handbooks in English 17 District Census Handbooks in Gujarati CONTENTS Pages PREFACE vii-xi ALPHABETICAL LIST OF VILLAGES xiii-xxii PART I (i) Introductory Essay . 1-37 (1) Location and Physical Features, (2) Administrative Set-up, (3) Local Self Government, (4) Population, (5) Housing, (6) Agriculture, (7) Livestock, (8) Irrigation, (9) Co-operation, (10) Economic Activity, (11) Industries and Power, (12) Transport and Communications, (13) Medical and Public Health, (14) Labour and Social Welfare, (15) Price Trends, (16) Community Development. -

Gujarat State Action Plan on Climate Change

Gujarat SAPCC: Draft Report GUJARAT Solar STATE ACTION PLAN ON CLIMATE CHANGE GOVERNMENT OF GUJARAT CLIMATE CHANGE DEPARTMENT Supported by The Energy and Resources Institute New Delhi & GIZ 2014 1 Gujarat SAPCC: Draft Report Contents Section 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 1.0 Introduction to Gujarat State Action Plan on Climate Change ............................................................. 3 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................................. 3 1.2 The State Action Plan on Climate Change .................................................................................... 5 2.0 Gujarat – An Overview ........................................................................................................................ 7 2.1Physiography and Climate ............................................................................................................ 7 2.2 Demography ................................................................................................................................ 8 2.3 Economic Growth and Development ........................................................................................... 9 2.4 Policies and Measures ............................................................................................................... 13 2.5 Institutions and Governance .................................................................................................... -

Geology of Kutch (Katchchh) and Ahmedabad Basin

ADS REPLY Point No. 1 District Survey Report as per the Ministry Notification S.O. No. 3611 (E) dated 25th July 2018. Reply District Survey Report has been prepared by district authorities in accordance with the MoEF Notification SO-141(E) dated 15th January 2016 on 04/08/2018, the same was submitted to MoEFCC and also enclosed herewith as AnnexureII. Ministry has amended SO-141(E) wherein the procedure for procedure for preparation of DSR for minor mineral was prescribed vide notification SO-3611(E) dated 25th July 2018 which is not availble with District Authorities. Point no.2 Status of the non-compliances of specific condition no. (ii), (xii) and (xv) and the general condition no. (VI) and (vii). Reply Status of the non-compliances of specific condition no. (ii), (xii) and (xv) and the general condition no. (VI) and (vii) is enclosed as Annexure III. 1 | Page M/s. UltraTech Cement Ltd (Unit: Sewagram Cement Works) M/s. UltraTech Cement Ltd. Index S. No. Annexures Documents Page No. 1. Annexure I Letter Issued by MoEFCC, Delhi on 6th March 2019 1-2 2. Annexure II District Survey Report as per the Ministry Notification S.O. 3-65 No. 3611 (E) dated 25th July 2018 3. Annexure III Status of the non-compliances of specific condition no. (ii), 66-128 (xii) and (xv) and the general condition no. (VI) and (vii) Annexure (a) - Wildlife compliance report. Annexure (b) - Greenbelt development/Plantation photograph. Annexure (c) – Rain water harvesting plan and Ground water study report. Annexure (d)- Water sprinkler photographs Annexure (e) - Noise level management report. -

Shri Mahaprabhuji's 84 Baithakji: 1. Shri Govindghat Baithakji Baithak Address:Near Govind Ghat, Gokul

Shri Mahaprabhuji's 84 Baithakji: 1. Shri Govindghat Baithakji Baithak Address:Near Govind Ghat, Gokul - 281303, Dist. Mathura, Uttar Pradesh. Village - Gokul Contact Person & Phone:Sureshbhai Mukhiyaji M: 093587 061 76, Amitbhai Mukhiyaji M: 096756 135 32 Nearby Railway Station:Mathura (From Mathura to Gokul 12 Km.) 2. Shri Badi Baithakji Baithak Address:Near Thakrani Ghat, Gokul - 281303, Dist. Mathura, Uttar Pradesh. Village - Gokul Contact Person & Phone:M: 097580 97 493 Nearby Railway Station:Mathura 3. Shri Shaichya Mandir Baithakji Baithak Address:Shaiya Mandir, Shri Dwarkadhish na Mandirma, Gokul - 281303, Dist. Mathura, Uttar Pradesh. Village - Gokul Contact Person & Phone:M: 097192 817 52, M: 097580 974 93 Nearby Railway Station:Mathura 4.Shri Vrundavan Bansivat Baithakji Baithak Address:Bansibat, Post Vrindaban - 281121, Dist. Mathura, Uttar Pradesh. Village - Vrindaban Contact Person & Phone:Purushotam Mukhiyaji M: 098979 793 26, 097604 498 47 Nearby Railway Station:Mathura (From Mathura 15 Km.) 5. Shri Vishram Ghat Baithakji Baithak Address:Near Vishram Ghat, Mathura - 281001, Uttar Pradesh. Village - Mathura Contact Person & Phone:Shri Vasantbhai Mukhiyaji M: 098370 166 42 Nearby Railway Station:Mathura 6. Shri Madhuvan Baithakji Baithak Address: AT Post Madhuvan - 281141, Maholi, Dist. Mathura, Uttar Pradesh. Village - MadhubanContact Person & Phone:Shri Jankiben M: 093199 912 31 Nearby Railway Station:Mathura (From Mathura 10 Km.) 7. Shri Kumudvan Baithakji Baithak Address:AT Post Kumudvan, Post Usfar (uspar or same par) - 281004, Dist. Mathura, Uttar Pradesh. Village - Kumudvan Contact Person & Phone:-- Nearby Railway Station:Mathura (From Mathura 20 Km.) 8. Shri Bahulavan Baithakji Baithak Address:Shri Bahulavan, Post Bati (Bati Gaon) - 281004 , Dist. Mathura, Uttar Pradesh. -

Religious Persecution in the Middle East; Faces of the Persecuted

S. HRG. 105±352 RELIGIOUS PERSECUTION IN THE MIDDLE EAST; FACES OF THE PERSECUTED HEARINGS BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON NEAR EASTERN AND SOUTH ASIAN AFFAIRS OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION May 1 and June 10, 1997 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Relations ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 40±890 CC WASHINGTON : 1998 COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS JESSE HELMS, North Carolina, Chairman RICHARD G. LUGAR, Indiana JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware PAUL COVERDELL, Georgia PAUL S. SARBANES, Maryland CHUCK HAGEL, Nebraska CHRISTOPHER J. DODD, Connecticut GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon JOHN F. KERRY, Massachusetts CRAIG THOMAS, Wyoming CHARLES S. ROBB, Virginia ROD GRAMS, Minnesota RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin JOHN ASHCROFT, Missouri DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California BILL FRIST, Tennessee PAUL D. WELLSTONE, Minnesota SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas JAMES W. NANCE, Staff Director EDWIN K. HALL, Minority Staff Director SUBCOMMITTEE ON NEAR EASTERN AND SOUTH ASIAN AFFAIRS SAM BROWNBACK, Kansas, Chairman GORDON H. SMITH, Oregon CHARLES S. ROBB, Virginia ROD GRAMS, Minnesota DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California JESSE HELMS, North Carolina PAUL D. WELLSTONE, Minnesota JOHN ASHCROFT, Missouri PAUL S. SARBANES, Maryland 2 CONTENTS Page RELIGIOUS PERSECUTION IN THE MIDDLE EASTÐTHURSDAY, MAY 1, 1997 Coffey, Steven J., Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of State, Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor ........................................................... 15 Phares, Dr. Walid, Professor of International -

Geological Bulletin Univ. Peshawar Vol. 35, Pp. 9-26,2002 M. ASIF

Geological Bulletin Univ. Peshawar Vol. 35, pp. 9-26,2002 M. ASIF KHAN', IFTIKHAR A .ABBASIZ,SHAMSUL HADI', AMANULLAH LAGHAR13 & ROGER BILHAM4 National Centre of Excellence in Geology, University of Peshawar 2Departmentof Geology, University of Peshawar Department of Geology, University of Sindh, Jamshoro "Department of Geological Sciences, University of Colorado, Boulder, USA ABSTRACT: The Bhuj Earthquake ofJanuary 26,2001 had devastating efects in India in terms of life andproperty loss. The epicenter beingwithin 150 krn from Pakistan'sSE border, shocks were felt over a wide region in Pakistan, resulting in wide-spread damage to buildings and a life loss of around 15people in the southeastern Sindh province ofPakistan. Thispaperpresents results of a field visit to the Thar-Nagar Parkar region ofSE Pakistan, outliningfeatures related with liquefaction andgroundfailuresas a consequence of the Bhuj Earthquake. These includesand blows in the inter- dunal depressions and Zateral spreadingat the crests and margins of the stable dunes. It has been noticed that a 170 km long belt of about 15 km width at thesouthern fringes of the Thar desert adjacent to the Great Rann of Kuchchh suffered widespread liquefaction, that resulted in damage to mud houses and cane huts in several villages, including the Tobo village (southeast ofDiplo) where25 30 such houses were completely orpartially collapsed. Na liquefaction was noticed at Nagar Parkar town (with bedrock asfoundation) as well as in the northemparts of the Thar desert (probably due to low water -

Report of the Committee for Gardens of Medicinal Plants Appointed by the Government of Gujarat

GUJARAT STATE Report of the Committee for Gardens of Medicinal Plants appointed by the Government of Gujarat * GOVERNMENT CENTRAL PRESS, AHMEDABAD 1969 [Price Rs. 1-40 Ps.] GUJARAT STATE Report of the Committee for Gardens of Medicinal Plants appointed by . the Government of Gujarat * THE COMMITTEE FOR GARDENS OF MEDICINAL PLANTS GUJARAT STATE Page No. 1 II Chairman ll RASIKLAL J. PARIKH H 17 Member• 24 Vaidya Shri Vasantbhai H. Gandhi Shri Zinabhai Darji, Vaidya Shri Shantibhai P. Joshi Presiden! : District Pancho: so Surat. · Vaidya Shri Vaghjibhai K. Solanki 38 Vaidya Shri Dalpat R. Vasani Shri Chunibhai Desaibhai Desai 411 Vaidya Shri Jivraj R. Siddhapura Shri S. J. Coelho, The Director of Industries 47 Gujarat State. 1 1)2 Shri R. D. Joshi, The Chief Conservator of Fore~ 116 Gujarat State, Baroda. 119 Shri B. V. Patel, Convener. The Director of Drugs Control Administration, . Gujarat State. o-188-(1) CONTENTS OHAPTER l'age No, I Appointment and Scope of the Committee. 1 II The Committee goes into action. II m Procedure adopted by the Committee, 9 IV Outline of the proceedinga. u v The Dange. 17 VI Gir and Girnar. 24 VII Kutch so VIII Danta and Jesor. sa IX Bhavnagar, Victoria Park. 411 X Vansda-Dharampur. 47 XI Pavagadh and Chhota Udepur. 1!2 XII Shetrunjaya and Ghela Somnath. 158 XIII Vijaynagar. 119 XIV Osam and Bardo ( Kileshvar ) 62 XV Ratan Mahal, Santrampur and Deogadh Barla. 69 XVI Batpuda and Narmada river bank region. 72 XVII- Conclusion. 81 XVIII- Summary of recommendations. Appendicee. 86 CHAPTER--I APPOINTMENT AND SCOPE OF THE COMMITTEE The Government of Gujarat had appointed a Committee for Gardens of Medicinal Plants under its.