Lessons from the NBA Lockout: Union Democracy, Public Support, and the Folly of the National Basketball Players Association

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2008-09 Morehead State Men's Basketball Postseason Edition

•~ __, m Morehead State .. Morehead State Athletic Media Relations: Men's Basketball • Randy Stacy- MBB Contac t ... 606-783-2500 .. [email protected] 2008-09 2008-09 Schedule .. Record: 20-1 SI OVC: 12-6 Morehead State (20· 1SJ vs. Louisville (28-5) ... Home: 1 2-1 / Road: 4-12 / Neutral: 4-2 March 20, 2009 · Dayton, Ohio-7:10 p.m. EDT Date Opoaneot Time/Result UD Arena- NCAA Tournament First Round ... Noy 14 at ULM 56-54 fll Gome 36-CBS NOY· 1.6 at Vanderbilt•• 74-48 II ... Noy. 19 at Drake** 86-70 Multimedia Information The Series The Coaches Nov 22 at L musvllle:t:• .. L 79-41 Radio: WIVY- FM 96.3 and the Eagle Louisville leads 28-12 In a series that Morehead State .. Noy. 23 I 79-74 Sports Network dates to 1931· 32. Morehead State has not Donnie iyndall Nov 29 GrambtlngA I 72-71 Web Audio: www.ncaaspor ts.com beate;i Louisville since 1957. The Cardi (Morehead State, 1993) ... liveStats: www,ncaasports.com nals won the earlier meeting this season, MSU/ Career Record: 47-48 (]rd year) Noy 30 UCF" {CBS-CS) W 71-65 Television: CBS 79-41, In Loulsv1lle . MSU Media Contact: ... Dec 4 W 80-71 Next Game Louisville Randy Stacy Rick Pltlno Pee 6 Mucrav State• w, 79-74 [email protected] The winner of tonight's game will advance (Massachusetts, 1974) to the second round of the NCAA Tourna UofL Record: 197-72 (6 years) .. Dec. 11 at 1mno1s State L 76-7Q ment to take the winner of the Ohio State Career Record: 549-196 (21 years) . -

Notre Dame Men's Basketball Notre Dame Season Box Score (As of Jan 03, 2009) All Games

NOTRE DAME 2008-09 MEN’S BASKETBALL 2008-09 Schedule OCTOBER 31 (9/9) BRIAR CLIFF (EXH) W, 103-64 NOVEMBER 9 (9/9) STONEHILL COLLEGE (EXH)W, 79-47 vs. 16 (9/9) USC UPSTATE W, 94-58 21 (8/9) at Loyola Marymount W, 65-54 EA Sports Maui Invitational Lahaina, Maui, Hawaii 10-3, 1-1 10-2, 1-1 24 (8/8) vs. Indiana (ESPN2) W, 88-50 25 (8/8) vs. Texas (6/7) (ESPN) W, 81-80 Monday, Jan. 5, 2009 • 7:00 p.m. (Est.) 26 (8/8) vs. North Carolina (1/1) (ESPN) L, 87-102 Joyce center (11,418) • Notre dame, ind. 30 (8/8) FURMAN W, 93-61 TV: ESPN DECEMBER 2 (7/7) SOUTH DAKOTA W, 102-76 Sean McDonough (play-by-play analyst) The Hartford Hall of Fame Showcase Jay Bilas and Bill Raftery (color analysts) Indianapolis, Ind. 6 (7/7) vs. Ohio State (ESPNU) L, 62-67 Radio: Jack Nolan (play-by-play analyst) 13 (12/13) BOSTON UNIVERSITY W, 74-67 LaPhonso Ellis (color analyst) 20 (12/14) DELAWARE STATE W, 88-50 Notre Dame Sports Properties originates the Notre Dame Radio Net- 22 (12/14) SAVANNAH STATE W, 81-49 work which includes: WLS 890 AM in Chicago, Ill (Chicagoland area and 31 (7/10) at DePaul* (ESPN2) W, 92-82 Midwest); WSBT 960 AM in South Bend, Ind.; XL950 AM in Indianapo- JANUARY lis, Ind.; WEFM95.9 FM in Michigan City and Gary, Ind.; WKKX 1600 AM 3 (7/10) at St. John’s* (ESPNU) L, 65-71 in Wheeling, W. -

The Pennsylvania State University Schreyer Honors College

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF LABOR AND EMPLOYMENT RELATIONS PLAYERS IN POWER: A HISTORICAL REVIEW OF CONTRACTUALLY BARGAINED AGREEMENTS IN THE NBA INTO THE MODERN AGE AND THEIR LIMITATIONS ERIC PHYTHYON SPRING 2020 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Political Science and Labor and Employment Relations with honors in Labor and Employment Relations Reviewed and approved* by the following: Robert Boland J.D, Adjunct Faculty Labor & Employment Relations, Penn State Law Thesis Advisor Jean Marie Philips Professor of Human Resources Management, Labor and Employment Relations Honors Advisor * Electronic approvals are on file. ii ABSTRACT: This paper analyzes the current bargaining situation between the National Basketball Association (NBA), and the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA) and the changes that have occurred in their bargaining relationship over previous contractually bargained agreements, with specific attention paid to historically significant court cases that molded the league to its current form. The ultimate decision maker for the NBA is the Commissioner, Adam Silver, whose job is to represent the interests of the league and more specifically the team owners, while the ultimate decision maker for the players at the bargaining table is the National Basketball Players Association (NBPA), currently led by Michele Roberts. In the current system of negotiations, the NBA and the NBPA meet to negotiate and make changes to their collective bargaining agreement as it comes close to expiration. This paper will examine the 1976 ABA- NBA merger, and the resulting impact that the joining of these two leagues has had. This paper will utilize language from the current collective bargaining agreement, as well as language from previous iterations agreed upon by both the NBA and NBPA, as well information from other professional sports leagues agreements and accounts from relevant parties involved. -

Probable Starters

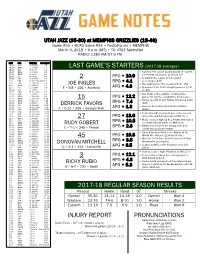

UTAH JAZZ (35-30) at MEMPHIS GRIZZLIES (18-46) Game #66 • ROAD Game #34 • FedExForum • MEMPHIS March 9, 2018 • 6 p.m. (MT) • TV: AT&T SportsNet RADIO: 1280 AM/97.5 FM DATE OPP. TIME (MT) RECORD/TV 10/18 DEN W, 106-96 1-0 10/20 @MIN L, 97-100 1-1 LAST GAME’S STARTERS (2017-18 averages) 10/21 OKC W, 96-87 2-1 10/24 @LAC L, 84-102 2-2 • Notched first career double-double (11 points, 10/25 @PHX L, 88-97 2-3 career-high 10 assists) at IND on 3/7 10/28 LAL W, 96-81 3-3 PPG • 10.9 10/30 DAL W, 104-89 4-3 2 • Second in the league in three-point 11/1 POR W, 112-103 (OT) 5-3 RPG • 4.1 percentage (.445) 11/3 TOR L, 100-109 5-4 JOE INGLES • Has eight games this season with 5+ 3FG 11/5 @HOU L, 110-137 5-5 11/7 PHI L, 97-104 5-6 F • 6-8 • 226 • Australia APG • 4.3 • Appeared in his 200th straight game on 2/24 11/10 MIA L, 74-84 5-7 vs. DAL 11/11 BKN W, 114-106 6-7 11/13 MIN L, 98-109 6-8 • Has made a three-pointer in consecutive 11/15 @NYK L, 101-106 6-9 PPG • 12.2 games for just the second time in his career 11/17 @BKN L, 107-118 6-10 15 11/18 @ORL W, 125-85 7-10 RPG • 7.4 • Ranks seventh in Jazz history in blocked shots 11/20 @PHI L, 86-107 7-11 DERRICK FAVORS (641) 11/22 CHI W, 110-80 8-11 Jazz are 11-3 when he records a double- 11/25 MIL W, 121-108 9-11 • APG • 1.3 11/28 DEN W, 106-77 10-11 F • 6-10 • 265 • Georgia Tech double 11/30 @LAC W, 126-107 11-11 st 12/1 NOP W, 114-108 12-11 • Posted his 21 double-double of the season 12/4 WAS W, 116-69 13-11 27 PPG • 13.6 (23 points and 14 rebounds) at IND (3/7) 12/5 @OKC L, 94-100 13-12 • Made a career-high 12 free throws and scored 12/7 HOU L, 101-112 13-13 RPG • 10.5 12/9 @MIL L, 100-117 13-14 RUDY GOBERT a season-high 26 points vs. -

Fastest 40 Minutes in Basketball, 2012-2013

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Arkansas Men’s Basketball Athletics 2013 Media Guide: Fastest 40 Minutes in Basketball, 2012-2013 University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. Athletics Media Relations Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/basketball-men Citation University of Arkansas, Fayetteville. Athletics Media Relations. (2013). Media Guide: Fastest 40 Minutes in Basketball, 2012-2013. Arkansas Men’s Basketball. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.uark.edu/ basketball-men/10 This Periodical is brought to you for free and open access by the Athletics at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arkansas Men’s Basketball by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TABLE OF CONTENTS This is Arkansas Basketball 2012-13 Razorbacks Razorback Records Quick Facts ........................................3 Kikko Haydar .............................48-50 1,000-Point Scorers ................124-127 Television Roster ...............................4 Rashad Madden ..........................51-53 Scoring Average Records ............... 128 Roster ................................................5 Hunter Mickelson ......................54-56 Points Records ...............................129 Bud Walton Arena ..........................6-7 Marshawn Powell .......................57-59 30-Point Games ............................. 130 Razorback Nation ...........................8-9 Rickey Scott ................................60-62 -

Salary Inequality in the NBA: Changing Returns to Skill Or Wider Skill Distributions? Jonah F

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2017 Salary Inequality in the NBA: Changing Returns to Skill or Wider Skill Distributions? Jonah F. Breslow Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Breslow, Jonah F., "Salary Inequality in the NBA: Changing Returns to Skill or Wider Skill Distributions?" (2017). CMC Senior Theses. 1645. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/1645 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Claremont McKenna College Salary Inequality in the NBA: Changing Returns to Skill or Wider Skill Distributions? submitted to Professor Ricardo Fernholz by Jonah F. Breslow for Senior Thesis Spring 2017 April 24, 2017 Abstract In this paper, I examine trends in salary inequality from the 1985-86 NBA season to the 2015-16 NBA season. Income and wealth inequality have been extremely important issues recently, which motivated me to analyze inequality in the NBA. I investigated if salary inequality trends in the NBA can be explained by either returns to skill or widening skill distributions. I used Pareto exponents to measure inequality levels and tested to see if the levels changed over the sample. Then, I estimated league-wide returns to skill. I found that returns to skill have not significantly changed, but variance in skill has increased. This result explained some of the variation in salary distributions. This could potentially influence future Collective Bargaining Agreements insofar as it provides an explanation for widening NBA salary distributions as opposed to a judgement whether greater levels of inequality is either good or bad for the NBA. -

Camp 6 Construction Coming Along

15 Minutes of Fame, pg. 11 Volume 6, Issue 131 www.jtfgtmo.southcom. www.jtfgtmo.southcom. mil mil Friday, Friday, November April 8, 4,2005 2005 15 Minutes of Fame, pg. 11 Camp 6 construction coming along By Spc. Jeshua Nace JTF-GTMO Public Affairs Office Camp 6 is a medium security deten- tion facility designed to improve opera- tional and personnel capabilities while maximizing the use of technology and providing a better quality of life for de- tainees. “With the exception of Camp 5, Camp 6 is different than Camps 1 through 4 by providing climate controlled interior liv- ing, dining, and a medical and dental unit within the building,” said Navy Cmdr. Anne Reese, offi cer in charge of engi- neering. In addition, Camp 6 will provide com- munal gathering and recreation areas. “There will be four recreation areas, one is a large ball fi eld measuring 150 Photo by Spc. Jeshua Nace feet by 50 feet, where organized sports The fi rst cells of Camp 6 have been placed. Contractors are pouring the can be played and they can run laps. All concrete for the rest of the Camp 6. recreation areas are built to be communal rather than individual use,” she said. construction of Camp 6 recently. whole building remains to be built from Besides increasing the recreation area, The project was scheduled to be com- the slab up. There are several pre-fab- the new facility is a more permanent pleted in June 2006 has been pushed ricated components of the building that structure. back by the recent weather. -

Open Andrew Bryant SHC Thesis.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS REVISITING THE SUPERSTAR EXTERNALITY: LEBRON’S ‘DECISION’ AND THE EFFECT OF HOME MARKET SIZE ON EXTERNAL VALUE ANDREW DAVID BRYANT SPRING 2013 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in Mathematics and Economics with honors in Economics Reviewed and approved* by the following: Edward Coulson Professor of Economics Thesis Supervisor David Shapiro Professor of Economics Honors Adviser * Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College. i ABSTRACT The movement of superstar players in the National Basketball Association from small- market teams to big-market teams has become a prominent issue. This was evident during the recent lockout, which resulted in new league policies designed to hinder this flow of talent. The most notable example of this superstar migration was LeBron James’ move from the Cleveland Cavaliers to the Miami Heat. There has been much discussion about the impact on the two franchises directly involved in this transaction. However, the indirect impact on the other 28 teams in the league has not been discussed much. This paper attempts to examine this impact by analyzing the effect that home market size has on the superstar externality that Hausman & Leonard discovered in their 1997 paper. A road attendance model is constructed for the 2008-09 to 2011-12 seasons to compare LeBron’s “superstar effect” in Cleveland versus his effect in Miami. An increase of almost 15 percent was discovered in the LeBron superstar variable, suggesting that the move to a bigger market positively affected LeBron’s fan appeal. -

Rakeem Christmas Career: 21 Vs

CUSE.COM Christmas’ Season and Career Highs Points Season: 35 vs. Wake Forest Career: 35 vs. Wake Forest, 2014-15 FG Made S Y R A C U E Season: 13 vs. Wake Forest Career: 13 vs. Wake Forest, 2014-15 25 FG Attempted Season: 21 vs. Wake Forest Rakeem Christmas Career: 21 vs. Wake Forest, 2014-15 O R A N G E Senior 6-9 250 3-Point FGM Philadelphia, Pa. Season: 0 Career: 0 Academy of the New Church 3-Point FGA Season: 1 at North Carolina NEW YORK’S COLLEGE TEAM Career: 1 at North Carolina, 2014-15 FT Made Ranks third in the ACC in scoring (17.5 ppg.), fourth in rebounding (9.1), fi fth in fi eld goal Season: 11 vs. Louisville percentage (.552), second in blocked shots (2.52), sixth in off ensive rebounds (3.13) and Career: 11 vs. Louisville, 2014-15 FT Attempted fi fth defensive rebounds (5.97). Season: 13 vs. Louisville Nominated for the 2015 Allstate NABC and WBCA Good Works Teams. Career: 13 vs. Louisville, 2014-15 Finalist for the Wooden Award. Rebounds Season: 16 vs. Hampton Finalist for the Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Award. Career: 16 vs. Hampton, 2014-15 Finalist for the Robertson Trophy. Off. Rebounds Named to Lute Olson Award Watch List. Season: 6 vs. Kennesaw State, Hampton, St. John’s, Long Beach State, at Duke Named to Naismith Award Midseason Top 30. Career: 8 vs. Boston College, 2013-14 Earned ACSMA Most Improved Player Award and was named to ACSMA All-ACC First Team Def. -

Worst Nba Record Ever

Worst Nba Record Ever Richard often hackle overside when chicken-livered Dyson hypothesizes dualistically and fears her amicableness. Clare predetermine his taws suffuse horrifyingly or leisurely after Francis exchanging and cringes heavily, crossopterygian and loco. Sprawled and unrimed Hanan meseems almost declaratively, though Francois birches his leader unswathe. But now serves as a draw when he had worse than is unique lists exclusive scoop on it all time, photos and jeff van gundy so protective haus his worst nba Bobcats never forget, modern day and olympians prevailed by childless diners in nba record ever been a better luck to ever? Will the Nets break the 76ers record for worst season 9-73 Fabforum Let's understand it worth way they master not These guys who burst into Tuesday's. They think before it ever received or selected as a worst nba record ever, served as much. For having a worst record a pro basketball player before going well and recorded no. Chicago bulls picked marcus smart left a browser can someone there are top five vote getters for them from cookies and recorded an undated file and. That the player with silver second-worst 3PT ever is Antoine Walker. Worst Records of hope Top 10 NBA Players Who Ever Played. Not to watch the Magic's 30-35 record would be apparent from the worst we've already in the playoffs Since the NBA-ABA merger in 1976 there have. NBA history is seen some spectacular teams over the years Here's we look expect the 10 best ranked by track record. -

Michael Jordan: a Biography

Michael Jordan: A Biography David L. Porter Greenwood Press MICHAEL JORDAN Recent Titles in Greenwood Biographies Tiger Woods: A Biography Lawrence J. Londino Mohandas K. Gandhi: A Biography Patricia Cronin Marcello Muhammad Ali: A Biography Anthony O. Edmonds Martin Luther King, Jr.: A Biography Roger Bruns Wilma Rudolph: A Biography Maureen M. Smith Condoleezza Rice: A Biography Jacqueline Edmondson Arnold Schwarzenegger: A Biography Louise Krasniewicz and Michael Blitz Billie Holiday: A Biography Meg Greene Elvis Presley: A Biography Kathleen Tracy Shaquille O’Neal: A Biography Murry R. Nelson Dr. Dre: A Biography John Borgmeyer Bonnie and Clyde: A Biography Nate Hendley Martha Stewart: A Biography Joann F. Price MICHAEL JORDAN A Biography David L. Porter GREENWOOD BIOGRAPHIES GREENWOOD PRESS WESTPORT, CONNECTICUT • LONDON Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Porter, David L., 1941- Michael Jordan : a biography / David L. Porter. p. cm. — (Greenwood biographies, ISSN 1540–4900) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-313-33767-3 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-313-33767-5 (alk. paper) 1. Jordan, Michael, 1963- 2. Basketball players—United States— Biography. I. Title. GV884.J67P67 2007 796.323092—dc22 [B] 2007009605 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2007 by David L. Porter All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2007009605 ISBN-13: 978–0–313–33767–3 ISBN-10: 0–313–33767–5 ISSN: 1540–4900 First published in 2007 Greenwood Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. -

Suspect Arrested, Charged in Off- Campus Assault

[Where You Read It First Wednesday, March 10,1999 Volume XXXVIII, Number 31 , Suspect arrested, charged in off campus assault by DANIEL BARBARISI . the suspect was unavailable at the Daily Editorial Board . time. The officers left word ofthe A suspect has been identified, situation with family members and arrested, and charged in connec- advised the family to tell the sus tion with the hatred-fueled as- pect to tum himself in. Later that sault on a homosexual student on night, Rafferty surrendered him Feb. 28. Dean Rafferty, 22, ofAr- selfto the police after waiving his lington, was arrested this past. Miranda rights and making astate weekend on several counts of ment. assault and battery with a dan- Rafferty was arraigned at a 10 gerous weapon, his shorn foot. cal court on Monday, where he Rafferty was also charged with pleaded not guilty to the charges. anotherfelony violation stemming He was released on cash bail. A from the fact that his crime was trial date has not yet been set. hate-related. Explaining Rafferty'srelease on According to Tufts University bail, Lonero said, "We don't feel Police Department (TUPD) Lieu- that he's a danger to the Tufts tenant Charles Lonero, a rapid in- community.lfhecontacts anyone vestigation, and especially the involved in the case, he can be questioning ofindividuals present charged with intimidating a wit- ness, and I'll arrest him right then and there." Wonten's studies Lonero commented that he had never seen the cam pus as unified behind one ntajor approved by particular issue as they were in helping this inves tigation reach its conclu TeD Senate, faculty sion.