Charlie Trippi: a Success Story

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1-1-17 at Los Angeles.Indd

WEEK 17 GAME RELEASE #AZvsLA Mark Dalton - Vice President, Media Relations Chris Melvin - Director, Media Relations Mike Helm - Manag er, Media Relations Matt Storey - Media Relations Coordinator Morgan Tholen - Media Relations Assistant ARIZONA CARDINALS (6-8-1) VS. LOS ANGELES RAMS (4-11) L.A. Memorial Coliseum | Jan. 1, 2017 | 2:25 PM THIS WEEK’S GAME ARIZONA CARDINALS - 2016 SCHEDULE The Cardinals conclude the 2016 season this week with a trip to Los Ange- Regular Season les to face the Rams at the LA Memorial Coliseum. It will be the Cardinals Date Opponent Loca on AZ Time fi rst road game against the Los Angeles Rams since 1994, when they met in Sep. 11 NEW ENGLAND+ Univ. of Phoenix Stadium L, 21-23 Anaheim in the season opener. Sep. 18 TAMPA BAY Univ. of Phoenix Stadium W, 40-7 Last week, Arizona defeated the Seahawks 34-31 at CenturyLink Field to im- Sep. 25 @ Buff alo New Era Field L, 18-33 prove its record to 6-8-1. The victory marked the Cardinals second straight Oct. 2 LOS ANGELES Univ. of Phoenix Stadium L, 13-17 win at Sea le and third in the last four years. QB Carson Palmer improved to 3-0 as Arizona’s star ng QB in Sea le. Oct. 6 @ San Francisco# Levi’s Stadium W, 33-21 Oct. 17 NY JETS^ Univ. of Phoenix Stadium W, 28-3 The Cardinals jumped out to a 14-0 lead a er Palmer connected with J.J. Oct. 23 SEATTLE+ Univ. of Phoenix Stadium T, 6-6 Nelson on an 80-yard TD pass in the second quarter and they held a 14-3 lead at the half. -

National College Football Awards Association

College Football Icons among Presenters for The Home Depot College Football Awards Airing Thursday, Dec. 8, at 9 p.m. ET on ESPN Presenters for this year’s The Home Depot College Football Awards - live on Thursday, Dec. 8, at 9 p.m. ET on ESPN – include five College Football Hall of Fame inductees and three former The Home Depot College Football Award winners. The show features the live presentation of nine player awards; the National College Football Awards Association (NCFAA) Contribution to College Football Award to Roy Kramer; The Home Depot Coach of the Year Award; The Allstate AFCA Good Works Team; the Disney Spirit Award; and student-athletes selected to the Walter Camp All-America Team. Presenters include: AWARD PRESENTER FINALISTS Matt Millen Dont’a Hightower, Alabama Chuck Bednarik Award Penn State, Tyrann Mathieu. LSU College Defensive Player of the Year ESPN College Football Analyst Devon Still, Penn State Fred Biletnikoff* Justin Blackmon, Oklahoma State* Biletnikoff Award Florida State, Ryan Broyles, Oklahoma Nation’s Most Outstanding Receiver Pro Football Hall of Fame Robert Woods, USC Judd Groza Randy Bullock, Texas A&M Lou Groza Collegiate Place-Kicker Ohio State, Dustin Hopkins, Florida State Nation’s Most Outstanding Placekicker Son of Lou Groza Caleb Sturgis, Florida Ray Guy* Ray Guy Award Southern Mississippi Ryan Allen, Louisiana Tech Nation’s Most Outstanding Punter Three-time Super Bowl Champion Steven Clark, Auburn Jackson Rice, Oregon Herschel Walker* Andrew Luck, Stanford Maxwell Award 1982 winner, Kellen Moore, -

December 3, 1982: Herschel Walker Wins the Heisman Trophy Learn More

December 3, 1982: Herschel Walker Wins the Heisman Trophy Learn More Suggested Readings Jim Benagh, Sports Great Herschel Walker (Hillside, N.J.: Enslow Publishers, 1990). S. H. Burchard, Herschel Walker (San Diego, Calif.: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1984). Jeff Prugh, Herschel Walker: From the Georgia Backwoods and the Heisman Trophy to the Pros (New York: Random House, 1983). Herschel Walker and Terry Todd, Herschel Walker's Basic Training (1985; reprint, New York: Doubleday, 1989). “Herschel Walker (b. 1962).” New Georgia Encyclopedia. http://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/nge/Article.jsp?id=h-2016&sug=y Herschel Walker Biography, Academy of Achievement: http://www.achievement.org/autodoc/page/wal0bio-1 Georgia Sports Hall of Fame PDF: http://gshf.org/pdf_files/inductees/football/herschel_walker.pdf www.todayingeorgiahistory.org December, 04, 1982: Herschel Walker Learn More Image Credits Vince Dooley Papers, MS 2363-23-005 Courtesy of the Georgia Historical Society Vince Dooley Papers, MS 2363-23-007 Courtesy of the Georgia Historical Society Herschel Walker and Vince Dooley, College Hall of Fame Image courtesy of University of Georgia Sports Communications Herschel Walker Heisman trophy Image courtesy of University of Georgia Sports Communications, 11871 www.todayingeorgiahistory.org Herschel Walker playing for the New Jersey Generals, 1983 Getty Images, 52286524 Herschel Walker, 1980 Image courtesy of University of Georgia Sports Communications, 197801 Herschel Walker Vince Dooley papers, MS2363-20-004 Courtesy of the Georgia Historical Society Herschel Walker Image courtesy of University of Georgia Sports Communications, 1742 Herschel Walker Image courtesy of University Georgia Sports Communications, 1750 www.todayingeorgiahistory.org Herschel Walker Image courtesy of University Georgia Sports Communications, 1752 Herschel Walker, outside Lovett Stadium, 1981 Getty Images, 52286514 Vince Dooley and Herschel Walker Image courtesy of University of Georgia Sports Communications, 11870 www.todayingeorgiahistory.org . -

Georgia Vs Clemson (9/19/1981)

Clemson University TigerPrints Football Programs Programs 1981 Georgia vs Clemson (9/19/1981) Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms Materials in this collection may be protected by copyright law (Title 17, U.S. code). Use of these materials beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. For additional rights information, please contact Kirstin O'Keefe (kokeefe [at] clemson [dot] edu) For additional information about the collections, please contact the Special Collections and Archives by phone at 864.656.3031 or via email at cuscl [at] clemson [dot] edu Recommended Citation University, Clemson, "Georgia vs Clemson (9/19/1981)" (1981). Football Programs. 150. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/fball_prgms/150 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Programs at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in Football Programs by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLEMSON h: Serving The Textile Finishing InUwBstrg LEADERS IN ENERGY CONSERVATION SUPPORTING TIGERS SINCE 1920 Manufacturers of Quality Textile Finishir)g Machir)ery MARSHALL and WlLUAMS COMPANY 46 Baker St., Providence, R. I. 02905 620 South Pleosanlburg Dr., Greenville, S. C. 29606 Area Code 401-461-3450 Area Code 803-242-6750 Contents Todav's Features Departments September 19, 1981 Today's Game and Statistics Clemson vs Georgia Today's Matchups Clemson Memorial Stadium Athletic Administration University Officials Cover Story 6 Stadium Information Jeff Davis is the leader for Clemson's de- fense and he v^^ill be tested today in his Athletic Dept. -

Hugginsscottauction Feb13.Pdf

elcome to Huggins and Scott Auctions, the Nation's fastest grow- W ing Sports & Americana Auction House. With this catalog, we are presenting another extensive list of sports cards and memo- rabilia, plus an array of historically significant Americana items. We hope you enjoy this. V E RY IMPORTA N T: DUE TO SIZE CONSTRAINTS AND T H E COST FAC TOR IN THE PRINT VERSION OF MOST CATA LOGS, WE ARE UNABLE TO INCLUDE ALL PICTURES AND ELA B O- R ATE DESCRIPTIONS ON EV E RY SINGLE LOT IN THE AUCTION. HOW EVER, OUR WEBSITE HAS NO LIMITATIONS, SO W E H AVE ADDED MANY MORE PH OTOS AND A MUCH MORE ELA B O R ATE DESCRIPTION ON V I RT UA L LY EV E RY ITEM ON OUR WEBSITE. WELL WO RTH CHECKING OUT IF YOU ARE SERIOUS ABOUT A LOT ! WEBSITE: W W W. H U G G I N S A N D S C OTT. C O M Here's how we are running our February 7, 2013 to STEP 2. A way to check if your bid was accepted is to go auction: to “My Bid List”. If the item you bid on is listed there, you are in. You can now sort your bid list by which lots you BIDDING BEGINS: hold the current high bid for, and which lots you have been Monday Ja n u a ry 28, 2013 at 12:00pm Eastern Ti m e outbid on. IF YOU HAVE NOT PLACED A BID ON AN ITEM BEFORE 10:00 pm EST (on the night the Our auction was designed years ago and still remains geared item ends), YOU CANNOT BID ON THAT ITEM toward affordable vintage items for the serious collector. -

Week 10 Game Release

WEEK 10 GAME RELEASE #BUFvsAZ Mark Dal ton - Senior Vice Presid ent, Med ia Rel ations Ch ris Mel vin - Director, Med ia Rel ations Mik e Hel m - Manag er, Med ia Rel ations Imani Sube r - Me dia Re latio ns Coordinato r C hase Russe ll - Me dia Re latio ns Coordinator BUFFALO BILLS (7-2) VS. ARIZONA CARDINALS (5-3) State Farm Stadium | November 15, 2020 | 2:05 PM THIS WEEK’S PREVIEW ARIZONA CARDINALS - 2020 SCHEDULE Arizona will wrap up a nearly month-long three-game homestand and open Regular Season the second half of the season when it hosts the Buffalo Bills at State Farm Sta- Date Opponent Loca on AZ Time dium this week. Sep. 13 @ San Francisco Levi's Stadium W, 24-20 Sep. 20 WASHINGTON State Farm Stadium W, 30-15 This week's matchup against the Bills (7-2) marks the fi rst of two games in a Sep. 27 DETROIT State Farm Stadium L, 23-26 five-day stretch against teams with a combined 13-4 record. Aer facing Buf- Oct. 4 @ Carolina Bank of America Stadium L 21-31 falo, Arizona plays at Seale (6-2) on Thursday Night Football in Week 11. Oct. 11 @ N.Y. Jets MetLife Stadium W, 30-10 Sunday's game marks just the 12th mee ng in a series that dates back to 1971. Oct. 19 @ Dallas+ AT&T Stadium W, 38-10 The two teams last met at Buffalo in Week 3 of the 2016 season. Arizona won Oct. 25 SEATTLE~ State Farm Stadium W, 37-34 (OT) three of the first four matchups between the teams but Buffalo holds a 7-4 - BYE- advantage in series aer having won six of the last seven games. -

All-Time All-America Teams

1944 2020 Special thanks to the nation’s Sports Information Directors and the College Football Hall of Fame The All-Time Team • Compiled by Ted Gangi and Josh Yonis FIRST TEAM (11) E 55 Jack Dugger Ohio State 6-3 210 Sr. Canton, Ohio 1944 E 86 Paul Walker Yale 6-3 208 Jr. Oak Park, Ill. T 71 John Ferraro USC 6-4 240 So. Maywood, Calif. HOF T 75 Don Whitmire Navy 5-11 215 Jr. Decatur, Ala. HOF G 96 Bill Hackett Ohio State 5-10 191 Jr. London, Ohio G 63 Joe Stanowicz Army 6-1 215 Sr. Hackettstown, N.J. C 54 Jack Tavener Indiana 6-0 200 Sr. Granville, Ohio HOF B 35 Doc Blanchard Army 6-0 205 So. Bishopville, S.C. HOF B 41 Glenn Davis Army 5-9 170 So. Claremont, Calif. HOF B 55 Bob Fenimore Oklahoma A&M 6-2 188 So. Woodward, Okla. HOF B 22 Les Horvath Ohio State 5-10 167 Sr. Parma, Ohio HOF SECOND TEAM (11) E 74 Frank Bauman Purdue 6-3 209 Sr. Harvey, Ill. E 27 Phil Tinsley Georgia Tech 6-1 198 Sr. Bessemer, Ala. T 77 Milan Lazetich Michigan 6-1 200 So. Anaconda, Mont. T 99 Bill Willis Ohio State 6-2 199 Sr. Columbus, Ohio HOF G 75 Ben Chase Navy 6-1 195 Jr. San Diego, Calif. G 56 Ralph Serpico Illinois 5-7 215 So. Melrose Park, Ill. C 12 Tex Warrington Auburn 6-2 210 Jr. Dover, Del. B 23 Frank Broyles Georgia Tech 6-1 185 Jr. -

17 Finalists for Hall of Fame Election

For Immediate Release For More Information, Contact: January 10, 2007 Joe Horrigan at (330) 456-8207 17 FINALISTS FOR HALL OF FAME ELECTION Paul Tagliabue, Thurman Thomas, Michael Irvin, and Bruce Matthews are among the 17 finalists that will be considered for election to the Pro Football Hall of Fame when the Hall’s Board of Selectors meets in Miami, Florida on Saturday, February 3, 2007. Joining these four finalists, are 11 other modern-era players and two players nominated earlier by the Hall of Fame’s Senior Committee. The Senior Committee nominees, announced in August 2006, are former Cleveland Browns guard Gene Hickerson and Detroit Lions tight end Charlie Sanders. The other modern-era player finalists include defensive ends Fred Dean and Richard Dent; guards Russ Grimm and Bob Kuechenberg; punter Ray Guy; wide receivers Art Monk and Andre Reed; linebackers Derrick Thomas and Andre Tippett; cornerback Roger Wehrli; and tackle Gary Zimmerman. To be elected, a finalist must receive a minimum positive vote of 80 percent. Listed alphabetically, the 17 finalists with their positions, teams, and years active follow: Fred Dean – Defensive End – 1975-1981 San Diego Chargers, 1981- 1985 San Francisco 49ers Richard Dent – Defensive End – 1983-1993, 1995 Chicago Bears, 1994 San Francisco 49ers, 1996 Indianapolis Colts, 1997 Philadelphia Eagles Russ Grimm – Guard – 1981-1991 Washington Redskins Ray Guy – Punter – 1973-1986 Oakland/Los Angeles Raiders Gene Hickerson – Guard – 1958-1973 Cleveland Browns Michael Irvin – Wide Receiver – 1988-1999 -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. IDgher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI A Bell & HoweU Information Compaiy 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 OUTSIDE THE LINES: THE AFRICAN AMERICAN STRUGGLE TO PARTICIPATE IN PROFESSIONAL FOOTBALL, 1904-1962 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State U niversity By Charles Kenyatta Ross, B.A., M.A. -

Game Release

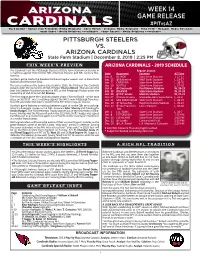

WEEK 14 GAME RELEASE #PITvsAZ Mark Dal ton - Senior Vice Presid ent, Med ia Re l ations Ch ris Mel vin - Director, Med i a Rel ations Mik e He l m - Manag e r, Me d ia Rel ations I mani Sub e r - Me dia R e latio n s Coo rdinato r C hase Russe l l - M e dia Re latio ns Coor dinat or PITTSBURGH STEELERS VS. ARIZONA CARDINALS State Farm Stadium | December 8, 2019 | 2:25 PM THIS WEEK’S PREVIEW ARIZONA CARDINALS - 2019 SCHEDULE The Cardinals host the Pi sburgh Steelers at State Farm Stadium on Sunday in Regular Season a matchup against their former NFL American Division and NFL Century Divi- Date Opponent Loca on AZ Time sion foe. Sep. 8 DETROIT State Farm Stadium T, 27-27 Sunday's game marks the Steelers third-ever regular season visit to State Farm Sep. 15 @ Bal more M&T Bank Stadium L, 23-17 Stadium and fi rst since 2011. Sep. 22 CAROLINA State Farm Stadium L, 38-20 The series between the teams dates back to 1933, the fi rst year the Cardinals Sep. 29 SEATTLE State Farm Stadium L, 27-10 played under the ownership of Hall of Famer Charles Bidwill. That was also the Oct. 6 @ Cincinna Paul Brown Stadium W, 26-23 year the Steelers franchise joined the NFL as the Pi sburgh Pirates under the Oct. 13 ATLANTA State Farm Stadium W, 34-33 ownership of Hall of Famer Art Rooney. Oct. 20 @ N.Y. Giants MetLife Stadium W, 27-21 The fi rst league game the Cardinals played under Charles Bidwill - which took Oct. -

Notre Dame Scholastic, Vol. 83, No. 04

m -^=6.^-'- »-^^ 'ante FOOTBALL NUMBER Volume 83, Number 4 December 7, 1944 Herein the Scholastic pays tribute to Coach Ed McKeever iinset) and the Fighting Irish of 1944 Price Twenty-five Cents ^he SYotre Q)ame Scholastic ^ ^^Ui^i/tc Disce Quasi Semper Victurus Vive Quasi Cras Moritums FOUNDED 1S67 It doesn't take much to get attention when you're a National Championship team, but after you drop a game or two, then, the descendancy from the ladder of fame seems to be the only alternative. But here's where the exception to the rule enters in — here at Notre Dame. For in defeat, the Fighting Irish of '44 were as great if not greater than the National Champions of '43. They left a great role to live up to, _/j those gridders of '43 when they took THE STAFF Bill Waddington leave of the scene — and consequently AL LESMEZ left a huge question mark hovering Editor-in-Chief over the campus all the winter and spring. From matur ity and experience to youth abounding with greenness— ED ITORI AL STAFF that was the fate of the Irish this season. The first re GENE DIAMOND - - - - Navy Associate Editor placement was the young Ed McKeever as head coach ROBERT RIORDAN ----- Managing Editor and with him three new additions to his staff of assist BILL WADDINGTON Sports Editor BOB OTOOLE ----- Circulation Manager ants. But this was only the beginning, for in the spring, only four monogram men had returned to the sod of COLUMN ISTS Cartier Field, until the return of Capt. -

Sports Defeat of Schroeder Flag Race Becomes * Four-Team Washington, D

Aussies Send World s Best Doubles Team After Davis Cup Clincher fknittg sports Defeat of Schroeder Flag Race Becomes * Four-Team Washington, D. C., Saturday, August 26,1950—B—9 By Young McGregor Dog Fight Shocks Americans As Red Sox March On By Will Grimsley fty th« Associated Press Attoclated Prill Sports Writer For the third time in as many FOREST HILLS, N. Y., Aug. seasons, the fence-busters from 26.—Australia sent the world’s Fenway Park are making bold best doubles team, wily John overtures to take the American Bromwich and slashing Frank Sedgman, against the United League pennant after poor starts. States today needing one victory The Sox ran out of gas the past Davis to recapture the Cup, em- two years but appear well sup- blem of international tennis plied for their latest bid. supremacy. Steve O’Neill’s men threw the Things never looked darker for race into a four-team dog fight Uncle Sam’s court covering last night as they turned back nephews, their backs nailed the league-leading Tigers, 6-2, for against the wall by a brace of bold their 11th straight victory. youngsters from Down Under who The triumph moved the Sox to within 3 V2 games of the Tigers Match on Television and reduced Detroit’s advantage The Davis Cup doubles over the runnerup Yankees and match at Forest Hills, N. Y., third-place Indians to IV2 games. will be televised starting at The Red Sox, however, trail 4 p.m. today over Station the Tigers by six games in the WNBW, channel 4.