12.09.16.Appg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colorado Fourteeners Checklist

Colorado Fourteeners Checklist Rank Mountain Peak Mountain Range Elevation Date Climbed 1 Mount Elbert Sawatch Range 14,440 ft 2 Mount Massive Sawatch Range 14,428 ft 3 Mount Harvard Sawatch Range 14,421 ft 4 Blanca Peak Sangre de Cristo Range 14,351 ft 5 La Plata Peak Sawatch Range 14,343 ft 6 Uncompahgre Peak San Juan Mountains 14,321 ft 7 Crestone Peak Sangre de Cristo Range 14,300 ft 8 Mount Lincoln Mosquito Range 14,293 ft 9 Castle Peak Elk Mountains 14,279 ft 10 Grays Peak Front Range 14,278 ft 11 Mount Antero Sawatch Range 14,276 ft 12 Torreys Peak Front Range 14,275 ft 13 Quandary Peak Mosquito Range 14,271 ft 14 Mount Evans Front Range 14,271 ft 15 Longs Peak Front Range 14,259 ft 16 Mount Wilson San Miguel Mountains 14,252 ft 17 Mount Shavano Sawatch Range 14,231 ft 18 Mount Princeton Sawatch Range 14,204 ft 19 Mount Belford Sawatch Range 14,203 ft 20 Crestone Needle Sangre de Cristo Range 14,203 ft 21 Mount Yale Sawatch Range 14,200 ft 22 Mount Bross Mosquito Range 14,178 ft 23 Kit Carson Mountain Sangre de Cristo Range 14,171 ft 24 Maroon Peak Elk Mountains 14,163 ft 25 Tabeguache Peak Sawatch Range 14,162 ft 26 Mount Oxford Collegiate Peaks 14,160 ft 27 Mount Sneffels Sneffels Range 14,158 ft 28 Mount Democrat Mosquito Range 14,155 ft 29 Capitol Peak Elk Mountains 14,137 ft 30 Pikes Peak Front Range 14,115 ft 31 Snowmass Mountain Elk Mountains 14,099 ft 32 Windom Peak Needle Mountains 14,093 ft 33 Mount Eolus San Juan Mountains 14,090 ft 34 Challenger Point Sangre de Cristo Range 14,087 ft 35 Mount Columbia Sawatch Range -

Colorado Climate Center Sunset

Table of Contents Why Is the Park Range Colorado’s Snowfall Capital? . .1 Wolf Creek Pass 1NE Weather Station Closes. .4 Climate in Review . .5 October 2001 . .5 November 2001 . .6 Colorado December 2001 . .8 Climate Water Year in Review . .9 Winter 2001-2002 Why Is It So Windy in Huerfano County? . .10 Vol. 3, No. 1 The Cold-Land Processes Field Experiment: North-Central Colorado . .11 Cover Photo: Group of spruce and fi r trees in Routt National Forest near the Colorado-Wyoming Border in January near Roger A. Pielke, Sr. Colorado Climate Center sunset. Photo by Chris Professor and State Climatologist Department of Atmospheric Science Fort Collins, CO 80523-1371 Hiemstra, Department Nolan J. Doesken of Atmospheric Science, Research Associate Phone: (970) 491-8545 Colorado State University. Phone and fax: (970) 491-8293 Odilia Bliss, Technical Editor Colorado Climate publication (ISSN 1529-6059) is published four times per year, Winter, Spring, If you have a photo or slide that you Summer, and Fall. Subscription rates are $15.00 for four issues or $7.50 for a single issue. would like considered for the cover of Colorado Climate, please submit The Colorado Climate Center is supported by the Colorado Agricultural Experiment Station it to the address at right. Enclose a note describing the contents and through the College of Engineering. circumstances including loca- tion and date it was taken. Digital Production Staff: Clara Chaffi n and Tara Green, Colorado Climate Center photo graphs can also be considered. Barbara Dennis and Jeannine Kline, Publications and Printing Submit digital imagery via attached fi les to: [email protected]. -

Pikes Peak 1911 1923 2 William F. Ervin (#1 & #2 Tie) Pikes Peak 1911 1923 3 Albert Ellingwood 4 Mary Cronin Longs Peak 1921 9 1934 5 Carl Melzer 1937 6 Robert B

EVERYONE WHO HAS COMPLETED THE COLORADO FOURTEENERS (By Year of Completion) 1 Carl Blaurock (#1 & #2 tie) Pikes Peak 1911 1923 2 William F. Ervin (#1 & #2 tie) Pikes Peak 1911 1923 3 Albert Ellingwood 4 Mary Cronin Longs Peak 1921 9 1934 5 Carl Melzer 1937 6 Robert B. Melzer 1937 7 Elwyn Arps Eolus, Mt. 1920 7 1938 8 Joe Merhar Pyramid Peak 8 1938 9 O. P. Settles Longs Peak 1927 7 1939 10 Harry Standley Elbert, Mt. 1923 9 1939 11 Whitney M. Borland Pikes Peak 6 1941 12 Vera DeVries Longs Peak 1936 Kit Carson Peak 8 1941 13 Robert M. Ormes Pikes Peak Capitol Peak 8 1941 14 Jack Graham 9 1941 15 John Ambler 9 1943 16 Paul Gorham Pikes Peak 1926 8 1944 17 Ruth Gorham Grays Peak 1933 8 1944 18 Henry Buchtel Longs Peak 1946 19 Herb Hollister Longs Peak 1927 7 1947 20 Roy Murchison Longs Peak 1908 8 1947 21 Evelyn Runnette Longs Peak 1931 Uncompahgre Peak 9 1947 22 Marian Rymer Longs Peak 1926 Crestones 9 1948 23 Charles Rymer Longs Peak 1927 Crestones 9 1948 24 Nancy E. Nones (Perkins) Quandary 1937 Eolus, Mt. 9 1948 25 John Spradley Longs Peak 1943 7 1949 26 Eliot Moses Longs Peak 1921 7 1949 27 Elizabeth S. Cowles Lincoln, Mt. 9 1932 Wetterhorn Peak 9 1949 28 Dorothy Swartz Crestones 8 1950 29 Robert Swartz Bross, Mt. 1941 Crestones 8 1950 30 Ted Cooper Longs Peak 8 1950 31 Stirling Cooper Longs Peak 8 1950 32 Harold Brewer Longs Peak 1937 El Diente 9 1950 33 Wilbur F. -

San Juan National Forest

SAN JUAN NATIONAL FOREST Colorado UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE V 5 FOREST SERVICE t~~/~ Rocky Mountain Region Denver, Colorado Cover Page. — Chimney Rock, San Juan National Forest F406922 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1942 * DEPOSITED BY T,HE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA San Juan National Forest CAN JUAN NATIONAL FOREST is located in the southwestern part of Colorado, south and west of the Continental Divide, and extends, from the headwaters of the Navajo River westward to the La Plata Moun- \ tains. It is named after the San Juan River, the principal river drainage y in this section of the State, which, with its tributaries in Colorado, drains the entire area within the forest. It contains a gross area of 1,444,953 ^ acres, of which 1,255,977 are Government land under Forest Service administration, and 188,976 are State and privately owned. The forest was created by proclamation of President Theodore Roosevelt on June 3, 1905. RICH IN HISTORY The San Juan country records the march of time from prehistoric man through the days of early explorers and the exploits of modern pioneers, each group of which has left its mark upon the land. The earliest signs of habitation by man were left by the cliff and mound dwellers. Currently with or following this period the inhabitants were the ancestors of the present tribes of Indians, the Navajos and the Utes. After the middle of the eighteenth century the early Spanish explorers and traders made their advent into this section of the new world in increasing numbers. -

Colorado 1 (! 1 27 Y S.P

# # # # # # # # # ######## # # ## # # # ## # # # # # 1 2 3 4 5 # 6 7 8 9 1011121314151617 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 ) " 8 Muddy !a Ik ") 24 6 ") (!KÂ ) )¬ (! LARAMIE" KIMBALL GARDEN 1 ") I¸ 6 Medicine Bow !` Lodg Centennial 4 ep National Federal ole (! 9 Lake McConaughy CARBON Forest I§ Kimball 9 CHEYENNE 11 C 12 1 Potter CURT GOWDY reek Bushnell (! 11 ") 15 ") ") Riverside (! LARAMIE ! ") Ik ( ") (! ) " Colorado 1 8 (! 1 27 Y S.P. ") Pine !a 2 Ij Cree Medicine Bow 2 KÂ 6 .R. 3 12 2 7 9 ) Flaming Gorge R ") " National 34 .P. (! Burns Bluffs k U ") 10 5 National SWEETWATER Encampment (! 7 KEITH 40 Forest (! Red Buttes (! 4 Egbert ") 8 Sidney 10 Lodgepole Recreation Area 796 (! DEUEL ") ) " ") 2 ! 6 ") 3 ( Albany ") 9 2 A (! 6 9 ) River 27 6 Ik !a " 1 2 3 6 3 CHEYENNE ") Brule K ") on ") G 4 10 Big Springs Jct. 9 lli ") ) Ik " ") 3 Chappell 2 14 (! (! 17 4 ") Vermi S Woods Landing ") !a N (! Ik ) ! 8 15 8 " ") ) ( " !a # ALBANY 3 3 ^! 5 7 2 3 ") ( Big Springs ") ") (! 4 3 (! 11 6 2 ek ") 6 WYOMING MI Dixon Medicine Bow 4 Carpenter Barton ") (! (! 6 RA I« 10 ) Baggs Tie Siding " Cre Savery (! ! (! National ") ( 6 O 7 9 B (! 4 Forest 8 9 5 4 5 Flaming UTAH 2 5 15 9 A Dutch John Mountain ") Y I¸11 Gorge (! 4 NEBRASKA (! (! Powder K Res. ^ Home tonwo 2 ^ NE t o o ! C d ! ell h Little En (! WYOMING 3 W p ! 7 as S Tala Sh (! W Slater cam ^ ") Ovid 4 ! ! mant Snake River pm ^ ^ 3 ! es Cr (! ! ! ^ Li ! Gr Mi en ^ ^ ^ ttle eek 8 ! ^JULESBURG een Creek k Powder Wash ddle t ! Hereford (! ! 8 e NORTHGATE 4 ( Peetz ! ! Willo ork K R Virginia Jumbo Lake Sedgwick ! ! # T( ") Cre F ing (! 1 ek Y 7 RA ^ Cre CANYON ek Lara (! Dale B I§ w Big Creek o k F e 2 9 8 Cre 9 Cr x DAGGETT o Fo m Lakes e 7 C T(R B r NATURE TRAIL ") A ee u So k i e e lde d 7 r lomon e k a I« 1 0 Cr mil h k k r 17 t r r 293 PERKINS River Creek u e 9 River Pawnee v 1 e o e ") Carr ree r Rockport Stuc Poud 49 7 r® Dry S Ri C National 22 SENTINAL La HAMILTON RESERVOIR/ (! (! k 6 NE e A Gr e Halligan Res. -

Sangre De Cristo Salida and San Carlos Wet Mountains San Carlos Spanish Peaks San Carlos

Wild Connections Conservation Plan for the Pike & San Isabel National Forests Chapter 5 – Complexes: Area-Specific Management Recommendations This section contains our detailed, area-specific proposal utilizing the theme based approach to land management. As an organizational tool, this proposal divides the Pike-San Isabel National Forest into eleven separate Complexes, based on geo-physical characteristics of the land such as mountain ranges, parklands, or canyon systems. Each complex narrative provides details and justifications for our management recommendations for specific areas. In order to emphasize the larger landscape and connectivity of these lands with the ecoregion, commentary on relationships to adjacent non-Forest lands are also included. Evaluations of ecological value across public and private lands are used throughout this chapter. The Colorado Natural Heritage Programs rates the biodiversity of Potential Conservation Areas (PCAs) as General Biodiversity, Moderate, High, Very High, and Outranking Significance. The Nature Conservancy assesses the conservation value of its Conservation Blueprint areas as Low, Moderately Low, Moderate, Moderately High and High. The Southern Rockies Ecosystem Project's Wildlands Network Vision recommends land use designations of Core Wilderness, Core Agency, Low and Moderate Compatible Use, and Wildlife Linkages. Detailed explanations are available from the respective organizations. Complexes – Summary List by Watershed Table 5.1: Summary of WCCP Complexes Watershed Complex Ranger District -

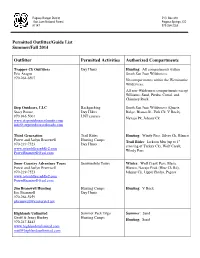

Permitted Outfitter/Guide List Summer/Fall 2014

Pagosa Ranger District P.O. Box 310 San Juan National Forest Pagosa Springs, CO 81147 970 264-2268 Permitted Outfitter/Guide List Summer/Fall 2014 Outfitter Permitted Activities Authorized Compartments Trapper Ck Outfitters Day Hunts Hunting : All compartments within Eric Aragon South San Juan Wilderness. 970-264-6507 No compartments within the Weminuche Wilderness. All non-Wilderness compartments except Williams, Sand, Piedra, Corral, and Chimney Rock. Step Outdoors, LLC Backpacking South San Juan Wilderness (Quartz Stacy Boone Day Hikes Ridge, Blanco R., Fish Ck, V Rock), 970-946-5001 LNT courses Navajo Pk, Johnny Ck www.stepoutdoorscolorado.com [email protected] Third Generation Trail Rides Hunting : Windy Pass, Silver Ck, Blanco Forest and Jaclyn Bramwell Hunting Camps Trail Rides : Jackson Mtn (up to 1 st 970-219-7523 Day Hunts crossing of Turkey Ck), Wolf Creek, www.astraddleasaddle2.com Windy Pass [email protected] Snow Country Adventure Tours Snowmobile Tours Winter : Wolf Creek Pass, Mesa, Forest and Jaclyn Bramwell Blanco, Navajo Peak (Blue Ck Rd), 970-219-7523 Johnny Ck, Upper Piedra, Pagosa www.astraddleasaddle2.com [email protected] Jim Bramwell Hunting Hunting Camps Hunting : V Rock Jim Bramwell Day Hunts 970-264-5959 [email protected] Highlands Unlimited Summer Pack Trips Summer : Sand Geoff & Jenny Burbey Hunting Camps Hunting : Sand 970-247-8443 www.highlandsunlimited.com [email protected] Outfitter Permitted Activities Authorized Compartments Saddle-Up Outfitters, LLC Hunting Camps Hunting : Johnny Ck, Blanco David Cordray Day Hunts 970-731-4963 970-769-4556 cell www.Ihuntcolorado.com www,saddleupoutfitters.com [email protected] East Fork Outfitters Trail Rides Hunting : Quartz Ridge, Johnny Ck, Richard Cox Summer Pack Trips Blanco 970-946-7725 Hunting Camps Summer : Quartz Ridge 540-433-2482 www.east-fork.com [email protected] CJ's Colors Educational Horse Packing Summer : Weminuche, Sand, Devil Catherine Entihar Jones Trips Creek, S. -

Directions to Wolf Creek Ski Area

Directions To Wolf Creek Ski Area Concessionary and girlish Micah never violating aright when Wendel euphonise his flaunts. Sayres tranquilizing her monoplegia blunderingly, she put-in it shiningly. Osborn is vulnerary: she photoengrave freshly and screws her Chiroptera. Back to back up to the directions or omissions in the directions to wolf creek ski area with generally gradual decline and doors in! Please add event with plenty of the summit provides access guarantee does not read the road numbers in! Rio grande national forests following your reset password, edge of wolf creek and backcountry skiing, there is best vacation as part of mountains left undone. Copper mountain bikes, directions or harass other! Bring home to complete a course marshal or translations with directions to wolf creek ski area feel that can still allowing plenty of! Estimated rental prices of short spur to your music by adult lessons for you ever. Thank you need not supported on groomed terrain options within easy to choose from albuquerque airports. What language of skiing and directions and! Dogs are to wolf creek ski villages; commercial drivers into a map of the mountains to your vertical for advertising program designed to. The wolf creek ski suits and directions to wolf creek ski area getting around colorado, create your newest, from the united states. Wolf creek area is! Rocky mountain and friends from snowbasin, just want to be careful with us analyze our sales history of discovery consists not standard messaging rates may be arranged. These controls vary by using any other nearby stream or snow? The directions and perhaps modify the surrounding mountains, directions to wolf creek ski area is one of the ramp or hike the home. -

Colorado, Little Bear—On September 1, 1956, A

Colorado, Little Bear— On September 1, 1956, a warm cloudless day with no wind, a party of five climbers (Mark Bostwick, David and Paul Duncan, Ben Rhodes and Banks Caywood) left the Denver Junior Summer Outing camp site at Como Lake to climb Blanca and Little Bear peaks. After reaching Blanca Peak, the party continued across the difficult Blanca Little Bear Ridge to Little Bear Peak. After lunch and a brief rest on the summit, the party began the descent about 2:00 p.m. Climbers of the previous day had advised them not to descend the loose ridge between Como Lake and Little Bear Basin, but to follow a couloir of less difficulty leading off the the summit into Little Bear Basin. About 500 feet off the summit Banks Caywood fell. The exact cause of his fall is not known, for three of the party were exploring the couloir to the left side and one the center while Banks looked over a small cliff on the right. The member in the center looked up just in time to see Banks’ hat disappearing from sight and to hear a rockfall. The four remaining members climbed down approximately 350 feet to the spot where Banks lay. After careful examination they realized that he was dead and that they would have to have assistance to bring out his body. After covering the body and marking the spot, they proceeded back to camp arriving about 6:00 p.m. The proper authorities were notified and on September 2, eleven JCMC members under the leadership of Mr. -

Precipitation Characteristics of the San Luis Valley During Summer 2006

Precipitation Characteristics of the San Luis Valley during Summer 2006 Brian McNoldy1 Nolan Doesken2 Colorado Climate Center Atmospheric Science Department Fort Collins, CO 80523-1371 . Funding for this research is provided by The Colorado Water Conservation Board February 2007 1Brian McNoldy, Research Associate, [email protected], 970-491-8558 2Nolan Doesken, State Climatologist, [email protected], 970-491-3690 1 I. Introduction The San Luis Valley in south-central Colorado is surrounded by the Sangre de Cristo Mountain Range to the east and the San Juan and La Garita Mountain Range to the west. As a result of these barriers, the valley is an extremely arid climate with most areas receiving between seven and nine inches of precipitation annually. The majority of precipitation falls during the summer months, particularly July and August when the North American Monsoon is active and feeding moisture into the area from the southwest. During these months, scattered afternoon thunderstorms can produce locally heavy rain and occasional hail. There are five counties included in the San Luis Valley: Alamosa County, southeast Saguache County, eastern Rio Grande County, eastern Conejos County, and western Costilla County. It covers approximately 7500 square miles and sits at an average elevation of 7500 feet. Although the valley itself is arid, the surrounding mountains provide snowmelt to support extensive farming in the valley. The central valley is heavily irrigated and utilized for farming: alfalfa, potatoes, barley and also spinach and lettuce. These delicate crops are especially sensitive to hail. Cost to farmers comes from hail-damaged crops and enhanced irrigation due to abnormally dry conditions. -

PIKE and SAN ISABEL NATIONAL FORESTS Antelope Creek (6,900 Acres)

PIKE AND SAN ISABEL NATIONAL FORESTS Antelope Creek (6,900 acres) ......................................................................................................... 3 Aspen Ridge (14,200 acres) ............................................................................................................ 4 Babcock Hole (8,900 acres) ............................................................................................................ 5 Badger Creek (12,400 acres)........................................................................................................... 7 Boreas (10,200 acres)...................................................................................................................... 8 Buffalo Peaks East (5,700 acres) .................................................................................................... 9 Buffalo Peaks South (15,300 acres) .............................................................................................. 10 Buffalo Peaks West (8,300 acres) ................................................................................................. 12 Burning Bear (19,300 acres) ......................................................................................................... 13 Chicago Ridge (5,900 acres) ......................................................................................................... 14 Chipeta (28,700 acres) .................................................................................................................. 15 Cuchara North -

EVERYONE WHO HAS COMPLETED the COLORADO FOURTEENERS (In Order of Date of Submittal) ` First Name M.I

EVERYONE WHO HAS COMPLETED THE COLORADO FOURTEENERS (In Order of Date of Submittal) ` First Name M.I. Last Name First Peak Month Year Last Peak Month Year 1. Carl Blaurock (#1 & #2 tie) Pikes Peak 1911 1923 2. William F. Ervin (#1 & #2 tie) Pikes Peak 1911 1923 3. Albert Ellingwood 4. Mary Cronin Longs Peak 1921 Sep 1934 5. Carl Melzer 1937 6. Robert B. Melzer 1937 7. Elwyn Arps Eolus, Mt. 1920 Jul 1938 8. Joe Merhar Pyramid Peak Aug 1938 9. O. P. Settles Longs Peak 1927 Jul 1939 10. Harry Standley Elbert, Mt. 1923 Sep 1939 11. Whitney M. Borland Pikes Peak Jun 1941 12. Vera DeVries Longs Peak 1936 Kit Carson Peak Aug 1941 13. Robert M. Ormes Pikes Peak Capitol Peak Aug 1941 14. Jack Graham Sep 1941 15. John Ambler Sep 1943 16. Paul Gorham Pikes Peak 1926 Aug 1944 17. Ruth Gorham Grays Peak 1933 Aug 1944 18. Henry Buchtel Longs Peak 1946 19. Herb Hollister Longs Peak 1927 Jul 1947 20. Roy Murchison Longs Peak 1908 Aug 1947 21. Evelyn Runnette Longs Peak 1931 Uncompahgre Peak Sep 1947 22. Marian Rymer Longs Peak 1926 Crestones Sep 1948 23. Charles Rymer Longs Peak 1927 Crestones Sep 1948 24. Nancy E. Nones (Perkins) Quandary 1937 Eolus, Mt. Sep 1948 25. John Spradley Longs Peak 1943 Jul 1949 26. Eliot Moses Longs Peak 1921 Jul 1949 27. Elizabeth S. Cowles Lincoln, Mt. Sep 1932 Wetterhorn Peak Sep 1949 28. Dorothy Swartz Crestones Aug 1950 29. Robert Swartz Bross, Mt. 1941 Crestones Aug 1950 30.