The Reasons for the Foundation of a British Settlement at Botany Bay in 1788

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

University of Wollongong Campus News 12 April 1985

THE UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG CAMPUS NEWS A WEEKLY INFORMATION SHEET 12 APRIL, 1985 Deadline for copy 12 noon Monday Distributed each Friday. Editor: Giles Pickford, tel. (042) 270073 HELPING IN THE PSYCHOLOGY DEPARTMENT A substantial research project, examining the processes involved in helping and being helped is in its second year. The project which is currently funded by a Uni- versity Research Grant, is conducted by Associate Professor Linda Viney, Dr. Rachael Henry and Dr. Beverly Walker. The initial aim is to develop a model depicting the various aspects of the help giving/help getting relationship. Following the trialing phase, it is hoped the model can be tested out in the various real life helping professions. An ARGS submission has been prepared, which if fruitful will assist in realizing this goal. At present the Department is seeking assistance from people who could devote a few hours to enable data collection. All information is confidential and respond- Associate Professor Viney ents are primarily asked to retell some experiences where they have helped somebody or received help be interested in participating, know someone who from someone. While we are looking for subjects of all could, or if you would just like some more information ages, we are finding it most difficult to locate subjects please contact Levinia Crooks, ext. 3640 Ph. 270640, in the 15-18, 30-50 and 60-80 age ranges. Should you or come to room 106 in the Psychology Department. *******************************************************************************************.****** GRADUATION SPEAKERS Friday, 3rd May 2.30 p.m. Education The following speakers have been confirmed for the Occasional Address: Professor Grant Harman, Head, Graduation Ceremonies being held 1-3 May, 1985. -

Macrobrachium Intermedium in Southeastern Australia: Spatial Heterogeneity and the Effects of Species of Seagrass

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 75: 239-249, 1991 Published September 11 Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. Demographic patterns of the palaemonid prawn Macrobrachium intermedium in southeastern Australia: spatial heterogeneity and the effects of species of seagrass Charles A. Gray* School of Biological Sciences, University of Sydney, 2006, NSW. Australia ABSTRACT. The effects of species of seagrass (Zostera capricorni and Posidonia australis) on spatial and temporal heterogeneity in the demography of estuarine populations of the palaemonid prawn Macrobrachium intermedium across 65 km of the Sydney region, southeastern Australia, were examined. Three estuaries were sampled in 1983 and 1984 to assess the magnitude of intra- and inter- estuary variability in demographic characteristics among populations. Species of seagrass had no effect on the demographic patterns of populations: differences in the magnitude and directions of change in abundances, recruitment, reproductive characteristics, size structures and growth were as great among populations within each species of seagrass as those between the 2 seagrasses Abiotic factors, such as the location of a meadow in relation to depth of water and distance offshore, and the interactions of these factors with recruiting larvae are hypothesised to have greater influence than the species of seagrass in determining the distribution and abundance of these prawns. Spatial and temporal heterogeneity in demography was similar across all spatial scales sampled: among meadows (50 m to 3 km apart) in an estuary and among meadows in all 3 estuaries (10 to 65 km apart). Variability in demographic processes among populations in the Sydney region was most likely due to stochastic factors extrinsic to the seagrasses then~selves.I conclude that the demography of seagrass-dwelling estuarine populations of M. -

Jellyfish Catostylus Mosaicus (Rhizostomeae) in New South Wales, Australia

- MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 196: 143-155,2000 Published April 18 Mar Ecol Prog Ser l Geographic separation of stocks of the edible jellyfish Catostylus mosaicus (Rhizostomeae) in New South Wales, Australia K. A. Pitt*, M. J. Kingsford School of Biological Sciences, Zoology Building, A08 University of Sydney, New South Wales 2006, Australia ABSTRACT: The population structure of the commercially harvested jellyfish Catostylus mosaicus (Scyphozoa, Rhizostomeae) was investigated in estuaries and bays in New South Wales, Australia. Variations in abundance and recruitment were studied in 6 estuaries separated by distances ranglng from 75 to 800 km. Patterns of abundance differed greatly among estuaries and the rank abundance among estuaries changed on 5 out of the 6 times sampling occurred. Great variation in the timing of recruitment was also observed among estuaries. Variations in abundance and recruitment were as extreme among nearby estuaries as distant ones. Broad scale sampling and detailed time series of abundance over a period of 2.7 yr at 2 locations showed no consistent seasonal trend in abundance at 1 location, but there was some indication of seasonality at the second location. At Botany Bay, the abun- dance of medusae increased with distance into the estuary and on 19 out of the 30 times sampling occurred medusae were found at sites adjacent to where rivers enter the bay. Medusae were found to be strong swimmers and this may aid medusae in maintaining themselves in the upper-reaches of estu- aries, where advection from an estuary is least likely. Variability in patterns of abundance and recruit- ment suggested regulation by processes occurring at the scale of individual estuaries and, combined with their relatively strong swimming ability, supported a model of population retention within estuar- ies. -

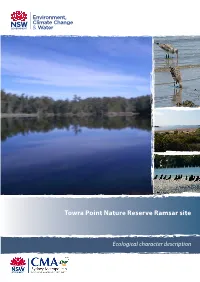

Towra Point Nature Reserve Ramsar Site: Ecological Character Description in Good Faith, Exercising All Due Care and Attention

Towra Point Nature Reserve Ramsar site Ecological character description Disclaimer The Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water NSW (DECCW) has compiled the Towra Point Nature Reserve Ramsar site: Ecological character description in good faith, exercising all due care and attention. DECCW does not accept responsibility for any inaccurate or incomplete information supplied by third parties. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the information in this publication for any particular purpose. Readers should seek appropriate advice about the suitability of the information to their needs. The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or of the Minister for Environment Protection, Heritage and the Arts. Acknowledgements Phil Straw, Australasian Wader Studies Group; Bob Creese, Bruce Pease, Trudy Walford and Rob Williams, Department of Primary Industries (NSW); Simon Annabel and Rob Lea, NSW Maritime; Geoff Doret, Ian Drinnan and Brendan Graham, Sutherland Shire Council; John Dahlenburg, Sydney Metropolitan Catchment Management Authority. Symbols for conceptual diagrams are courtesy of the Integration and Application Network (ian.umces.edu/symbols), University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. This publication has been prepared with funding provided by the Australian Government to the Sydney Metropolitan Catchment Management Authority through the Coastal Catchments Initiative Program. © State of NSW, Department of Environment, Climate Change and Water NSW, and Sydney Metropolitan Catchment Management Authority DECCW and SMCMA are pleased to allow the reproduction of material from this publication on the condition that the source, publisher and authorship are appropriately acknowledged. -

Coastal Storms in Nsw and Their Effect on the Coast

I I. COASTAL STORMS IN N.s.w. .: AUGUST & NOVEMBER 1986 .1 and Their Effect on the Coast I 'I I 1'1 ! I I I I I I I I I I , . < May 198,8 , 'I " I I : COASTAL STORMS· IN N.s.w. I AUGUST & NOVEMBER 1986 I and Their Effect on the Coast I I I I I 1: 1 I I I I I M.N. CLARKE M.G. GEARY I Chief Engineer Principal Engineer I Prepared by : University of N.S.W. Water Research Laboratory I bID IPTIID311IIcr: ~Th'¥@~ , I May 1988 ------..! Coaat a Rivera Branch I I I I CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ( ii ) I LIST OF TABLES (iv) 1. INTRODUCTION I 2. SUMMARY 2 3. ENVIRONMENTAL CONDITIONS 5 I 3.1 METEOROLOGICAL DATA 5 3.2 TIDE LEVELS 7 3.3 WAVE HEIGHTS AND PERIODS 10 I 3.4 STORM mSTORY - AUGUST 1985 TO AUGUST 1986 13 4. WAVE RUN-UP 15 I 4.1 MANLY WARRINGAH BEACHES 15 4.2 BATEMANS BAY BEACHES 15 I 4.3 THEORETICAL ASSESSMENT 16 4.4 COMPARISON OF MEASURED AND THEORETICAL RUN-UP LEVELS 23 5. BEACH SURVEYS 25 ·1 5.1 GOSFORD BEACHES 25 5.2 MANLY W ARRINGAH BEACHES 28 I 5.3 BATEMANS BAY BEACHES 29 6. OFFSHORE SURVEYS . 30 6.1 SURVEY METHODS 30 I 6.2 GOSFORD BEACHES 30 6.3 WARRINGAH BEACHES 31 I 6.4 ASSESSMENT OF ACCURACY OF OFFSHORE SURVEYS 32 7. OFFSHORE SEDIMENT SAMPLES - GOSFORD BEACHES 34 7.1 SAMPLE COLLECTION 34 I 7.2 SAMPLE CLASSIFICATION 34 , 7.3 SAMPLE DESCRIPTIONS 34 I 7.4 COMPARISON OF 1983/84 AND POST STORM OFFSHORE DATA 36 8. -

![An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales [Volume 1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2437/an-account-of-the-english-colony-in-new-south-wales-volume-1-822437.webp)

An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales [Volume 1]

An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales [Volume 1] With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners &c. of the Native Inhabitants of that Country. To Which are Added, Some Particulars of New Zealand: Complied by Permission, From the Mss. of Lieutenant-Governor King Collins, David (1756-1810) A digital text sponsored by University of Sydney Library Sydney 2003 colacc1 http://purl.library.usyd.edu.au/setis/id/colacc1 © University of Sydney Library. The texts and images are not to be used for commercial purposes without permission Prepared from the print edition published by T. Cadell Jun. and W. Davies 1798 All quotation marks are retained as data. First Published: 1798 F263 Australian Etext Collections at Early Settlement prose nonfiction pre-1810 An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales [Volume 1] With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners &c. of the Native Inhabitants of that Country. To Which are Added, Some Particulars of New Zealand: Complied by Permission, From the Mss. of Lieutenant-Governor King Contents. Introduction. SECT. PAGE I. TRANSPORTS hired to carry Convicts to Botany Bay. — The Sirius and the Supply i commissioned. — Preparations for sailing. — Tonnage of the Transports. — Numbers embarked. — Fleet sails. — Regulations on board the Transports. — Persons left behind. — Two Convicts punished on board the Sirius. — The Hyæna leaves the Fleet. — Arrival of the Fleet at Teneriffe. — Proceedings at that Island. — Some Particulars respecting the Town of Santa Cruz. — An Excursion made to Laguna. — A Convict escapes from one of the Transports, but is retaken. — Proceedings. — The Fleet leaves Teneriffe, and puts to Sea. -

Regional Pest Management Strategy 2012-2017: Metro North East

Regional Pest Management Strategy 2012–17: Metro North East Region A new approach for reducing impacts on native species and park neighbours © Copyright State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage With the exception of photographs, the Office of Environment and Heritage and State of NSW are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial use, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specific permission is required for the reproduction of photographs. The New South Wales National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) is part of the Office of Environment and Heritage. Throughout this strategy, references to NPWS should be taken to mean NPWS carrying out functions on behalf of the Director General of the Department of Premier and Cabinet, and the Minister for the Environment. For further information contact: Metro North East Region Metropolitan and Mountains Branch National Parks and Wildlife Service Office of Environment and Heritage PO Box 3031 Asquith NSW 2077 Phone: (02) 9457 8900 Report pollution and environmental incidents Environment Line: 131 555 (NSW only) or [email protected] See also www.environment.nsw.gov.au/pollution Published by: Office of Environment and Heritage 59–61 Goulburn Street, Sydney, NSW 2000 PO Box A290, Sydney South, NSW 1232 Phone: (02) 9995 5000 (switchboard) Phone: 131 555 (environment information and publications requests) Phone: 1300 361 967 (national parks, climate change and energy efficiency information and publications requests) Fax: (02) 9995 5999 TTY: (02) 9211 4723 Email: [email protected] Website: www.environment.nsw.gov.au ISBN 978 1 74293 625 3 OEH 2012/0374 August 2013 This plan may be cited as: OEH 2012, Regional Pest Management Strategy 2012–17, Metro North East Region: a new approach for reducing impacts on native species and park neighbours, Office of Environment and Heritage, Sydney. -

COOK, CUNNINGHAM, HUGHES, MACARTHUR, THROSBY And

BELLS LIN E OF RD RD Riv g C K Y IL k RD ay 1 L Howes Cape Three Points Creek L R Bellbird Hill Hawkesbury D RD R Pie Dish Hill Y Y Cogra Hill DEMONDR Campbells O RR R FE Ettalong RD Mourawaring Point RLY E Bar P L MANS oint M WISE D G D O R R R C E Umina SCENIC E N L A R L T F I THE Belubula Chifley Dam E O V - T K R C D RD S A E E Coxs IN S Bombi Point Y W L E Carcoar N Y RD A A Lake Y G L ON B BELLS W T H PA N I Hawkesbury River A Grose D M R Fish I Grose TA S T A NORTHERN E C River E V K River U C A R R River C R AJ O O F Broken Bay NG R River E River RD B L I D HORNSBY WESTERN W D L W R O IND Y SOR FW RIC BLACKTOW HMON N D W River RD O IC River T IF C JENOLAN A P ITT E N RD T P L S RD T BAY S D A 2 C R D IE Campbells R R W Pittwater A E U N Q Lake C D A R M Rowlands River D R Y E PITTWATER W N BLACKTOWN -IN BAULKHAM HILLS D River D Y S 9 O G S R ALS ESBURY TO Y HAWK N E RD JO H N H D E G R LITHGOW W R A R Y E 2 R R BA E I D L C R W R R T H COOK, CUNNINGHAM, HUGHES, D E I S M C MACQUARIERiver S T H 1 E A O R N M N C D MACKELLAR Lake Oberon O RD N VA S L T D E E A N D 3 V E A M R ON R E A A E G H C MITCHELL H H MACKELLAR W T 10 Y Nepean R R Duckmaloi O L N MACARTHUR, THROSBY and WERRIWA Y MITCHELL R L STERN Y W WE IN MAIN D RD N I D F S 3 F B R O O O R B R R O E Little River E B S W S T E T STLIN GREENWAYK PKW RD M7 CA VALE Y ST Fish LE 7 THE Y A H W N I H O Campbells LL M W CALARE Kedumba RD P W Little BLACKTOWN A NORTH River R WARRINGAH Y BRADFIELDKU-RING-GAI Y C BLUE D I F CHIFLEY I Lane C MAIN BRADFIELD JENOLAN LINDSAY CALARE CHIFLEYRLY -

And Domestic Politics, 1800-1804. by Charles John Fedorak London

The Addington Ministry and the Interaction of Foreign Policy and Domestic Politics, 1800-1804. by Charles John Fedorak London School of Economics and Political Science Submitted in requirement for the degree of PhD, University of London, 1990. UMI Number: U048269 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U048269 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 TH"£Sc S F 776y 2 Abstract Historians have generally dismissed the ministry of Henry Addington as an absurd interlude in the political career of William Pitt, the Younger, and the few attempts to rehabilitate Addington have been unable to overcome the weight of this negative historiography. The focus of contemporary and historical criticism has centred on the foreign and war policies of the ministry, but this has failed to take into account the serious and interrelated diplomatic, military, social, and political problems faced by the government. Social unrest caused largely by high prices of grain, political pressure from interests that had been hurt by the closure of European markets to British trade, and a poor diplomatic and strategic position meant that peace was highly desirable but that concessions were necessary to obtain it. -

Historic Oddities & Strange Events 1St Series

Historic Oddities & Strange Events 1st Series By Sabine Baring Gould Historic Oddities & Strange Events, 1st Series I. — THE DISAPPEARANCE OF BATHURST THE mystery of the disappearance of Benjamin Bathurst on November 25, 1809, is one which can never with certainty be cleared up. At the time public opinion in England was convinced that he had been secretly murdered by order of Napoleon, and the Times in a leader on January 23, 1810, so decisively asserted this, that the Moniteur of January 29 ensuing, in sharp and indignant terms repudiated the charge. Nevertheless, not in England only, but in Germany, was the impression so strong that Napoleon had ordered the murder, if murder had been committed, that the Emperor saw fit, in the spring of the same year, solemnly to assure the wife of the vanished man, on his word of honour, that he knew nothing about the disappearance of her husband. Thirty years later Varnhagen von Ense, a well-known German author, reproduced the story and reiterated the accusation against Napoleon, or at all events against the French. Later still, the Spectator, in an article in 1862, gave a brief sketch of the disappearance of Bathurst, and again repeated the charge against French police agents or soldiers of having made away with the Englishman. At that time a skeleton was said to have been discovered in the citadel of Magdeburg with the hands bound, in an upright position, and the writer of the article sought to identify the skeleton with the lost man. We shall see whether other discoveries do not upset this identification, and afford us another solution of the problem—What became of Benjamin Bathurst? Benjamin Bathurst was the third son of Dr. -

Admiral Arthur Phillip.Pdf

Admiral Arthur Phillip, R.N. (1738 – 1814) A brief story by Angus Ross for the Bread Street Ward Club, 2019 One of the famous people born in Bread Street was Admiral Arthur Phillip, R.N, the Founder of Australia and first Governor of New South Wales (1788-1792). His is a fascinating story that only recently has become a major subject of research, especially around his naval exploits, but also his impact in the New Forest where he lived mid-career and also around Bath, where he finally settled and died. I have studied records from the time Phillip sailed to Australia, a work published at the end of the 19c and finally from more recent research. Some events are reported differently by different observes or researchers so I have taken the most likely record for this story. Arthur Phillip in later life His Statue in Watling Street, City of London I have tried to balance the amount of detail without ending up with too long a story. It is important to understand the pre-First Fleet Phillip to best understand how he was chosen and was so well qualified and experienced to undertake the journey and to establish the colony. So, from a range of accounts written in various times, this story aims to identify the important elements of Phillip’s development ending in his success in taking out that First Fleet, made up primarily of convicts and marines, to start the first settlement. I have concluded this story with something about the period after he returned from Australia and what recognition of his life and achievements are available to see today. -

Their Stories

NORTH YORKSHIRE’S UNSUNG HEROES THEIR STORIES Acknowledgements We are indebted to the men and women who have given their time to share their valuable stories and kindly allowed us to take copies of their personal photographs. We are also extremely grateful to them for allowing their personal histories to be recorded for the benefit of current and future generations. In addition, we would like to thank Dr Tracy Craggs, who travelled the length and breadth of North Yorkshire to meet with each of the men and women featured in this book to record their stories. We would also like to thank her – on behalf of the Unsung Heroes – for her time, enthusiasm and kindness. © Copyright Community First Yorkshire, 2020 All rights reserved. The people who have shared their stories for this publication have done so with the understanding that they will not be reproduced without prior permission of the publisher. Any unauthorised copying or reproduction will constitute an infringement of copyright. Contents Foreword 3 Introduction 4 Their stories 5 – 45 Glossary 46 NORTH YORKSHIRE’S UNSUNG HEROES I THEIR STORIES Foreword North Yorkshire has a strong military history and a continuing armed forces presence. The armed forces are very much part of our local lives – whether it’s members of our own families, the armed forces’ friends in our children’s schools, the military vehicles on the A1, or the jets above our homes. The serving armed forces are visible in our county – but the older veterans, our unsung heroes, are not necessarily so obvious. With the Ex-Forces Support North Yorkshire project we wanted to raise the profile of older veterans across North Yorkshire.