Student Personality Characteristics and Optimal College Learning Conditions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

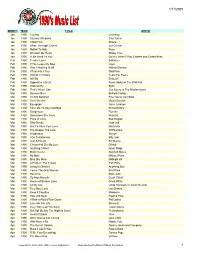

311 Creatures

311 Creatures (For A While) 10 Years After I'd Love To Change The World 10,000 Maniacs Because The Night 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants 10,000 Maniacs Like The Weather 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are Days 10,000 Maniacs Trouble Me 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc The Things We Do For Love 112 Come See Me 112 Cupid 112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 112 Peaches & Cream 112Super Cat Na Na Na 1910 Fruitgum Co. 1 2 3 Red Light 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 2Pac California Love 2Pac Changes 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac How Do You Want It 2Pau Heart And Soul 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Be Like That 3 Doors Down Duck And Run 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down The Road I'm On 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 3 Of Hearts Arizon Rain 311 All Mixed Up 311 Amber 311 Down 311 I'll Be Here Awhile 311 You Wouldn't Believe 38 Special Caught Up In You 38 Special Hold On Loosely 38 Special Rockin' Into The Night 38 Special Second Chance 38 Special Wild Eyed Southern Boys 3LW I Do 3LW No More Baby 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3rd Stroke No Light 4 Non Blondes What's Up 4 PM Sukiyaki 4 Runner Cain's Blood 4 Runner Ripples 4Him Basics Of Life 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 cent pimp 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Wanksta 5th Dimension Aquarius 5th Dimension Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 5th Dimension One Less Bell To Answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up And Away 5th Dimension Wedding Bell Blues 69 Boyz Tootie Roll 702 Get It Together 702 Steelo 702 Where My -

To All the Ends of the Earth

September 26 , 2008 · Volume 56 · Issue 2 THEA California BANNER Baptist University Campus Publication LEE LYONS PAGE 3 ∙ SODOKU PAGE 7∙ SOCCER 16 ∙ TO ALL THE ENDS OF THE EARTH BY ALYSSA ISGETT Though USP trips will only be CULTURE & PERSPECTIVE EDITOR ten days over Thanksgiving break, Spring break, and early May for “But you will receive power Summer vacation, three week trips when the Holy Spirit comes may be added in the future. “At the on you; and you will be my end of the year, we will evaluate witnesses in Jerusalem, and in how the trips go and the student all Judea and Samaria, and to the response to the trips,” Dobbins ends of the earth,” Acts 1:8. said. The Office of Mobilization The New York trips will mostly has added a new set of mission work with new churches. The team opportunities for students to live will do ethnography, going out out the great commission. “Our talking to people, seeing who is desire is to be holistic in that in the community and what the we are obedient to minister to different needs are. Much of the trip the ends of the earth as well as will consist of servant evangelism. locally,” Jared Dobbins, Assistant The same goes for Baltimore and Director of Global Mobilization, to some degree, San Diego. The said. Utah and Hawaii teams will work Many students at California with University students. The Baptist University have either Utah team will stay directly across experienced first hand or heard from Weber University and have of International Service Projects. -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

© 2017 Star Party Karaoke 17 Cross Canadian Ragweed 45 Shinedown 98.6 Keith 247 Artful Dodger Feat

Numbers Song Title © 2017 Star Party Karaoke 17 Cross Canadian Ragweed 45 Shinedown 98.6 Keith 247 Artful Dodger Feat. Melanie Blatt 409 Beach Boys, The 911 Wyclef Jean & Mary J Blige 1969 Keith Stegall 1979 Smashing Pumpkins, The 1982 Randy Travis 1985 Bowling For Soup 1999 Prince 1999 Wilkinsons, The 5678 Step #1 Crush Garbage 1, 2 Step Ciara Feat. Missy Elliott 1, 2, 3 Redlight 1910 Fruitgum Co 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys, The 100 Years Five For Fighting 100 Years From Now Huey Lewis & The News 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 16th Avenue Lacy J Dalton 18 & Life Skid Row 18 Till I Die Bryan Adams 18 Yellow Roses Bobby Darin 19-2000 Gorillaz 19th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc 20th Century Fox Doors, The 21 Questions 50 Cent Feat Nate Dogg 24 Hours At A Time Marshall Tucker Band, The 24-7 Kevon Edmonds 25 Miles Edwin Starr 25 Minutes Michael Learns To Rock 25 Minutes To Go Johnny Cash 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The 29 Nights Danni Leigh 29 Palms Robert Plant 3 Strange Days School Of Fish 30 Days In The Hole Humble Pie 30,000 Pounds Of Bananas Harry Chapin 32 Flavours Alana Davis 4 In The Morning Gwen Stefani 4 Seasons Of Loneiness Boyz 2 Men 4 To 1 In Atlanta Tracy Byrd 4+20 Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young 42nd Street Broadway Show “42nd Street” 455 Rocket Kathy Mattea 4th Of July Shooter Jennings 5 Miles To Empty Brownstone 50,000 Names George Jones 50/50 Lemar 500 Miles (Away From Home) Bobby Bare -

Triller Network Acquires Verzuz: Exclusive

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE APRIL 13, 2020 | PAGE 4 OF 19 ON THE CHARTS JIM ASKER [email protected] Bulletin SamHunt’s Southside Rules Top Country YOURAlbu DAILYms; BrettENTERTAINMENT Young ‘Catc NEWSh UPDATE’-es Fifth AirplayMARCH 9, 2021 Page 1 of 25 Leader; Travis Denning Makes History INSIDE Triller Network Acquires Sam Hunt’s second studio full-length, and first in over five years, Southside sales (up 21%) in the tracking week. On Country Airplay, it hops 18-15 (11.9 mil- (MCA Nashville/Universal Music Group Nashville), debuts at No. 1 on Billboard’s lion audience impressions, up 16%). Top Country• Verzuz Albums Founders chart dated April 18. In its first week (endingVerzuz: April 9), it Exclusive earnedSwizz 46,000 Beatz equivalent & album units, including 16,000 in album sales, ac- TRY TO ‘CATCH’ UP WITH YOUNG Brett Youngachieves his fifth consecutive cordingTimbaland to Nielsen Talk Music/MRC Data. andBY total GAIL Country MITCHELL Airplay No. 1 as “Catch” (Big Machine Label Group) ascends SouthsideTriller Partnership: marks Hunt’s second No. 1 on the 2-1, increasing 13% to 36.6 million impressions. chart‘This and fourthPuts a top Light 10. It followsVerzuz, freshman the LPpopular livestream music platform creat- in music todayYoung’s than Verzuz,” first of six said chart Bobby entries, Sarnevesht “Sleep With,- MontevalloBack on, which Creatives’ arrived at theed summit by Swizz in No Beatz- and Timbaland, has been acquired executive chairmanout You,” andreached co-owner No. 2 in of December Triller, in 2016. an- He vember 2014 and reigned for nineby weeks. Triller To Network, date, parent company of the Triller app. -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

1990S Playlist

1/11/2005 MONTH YEAR TITLE ARTIST Jan 1990 Too Hot Loverboy Jan 1990 Steamy Windows Tina Turner Jan 1990 I Want You Shana Jan 1990 When The Night Comes Joe Cocker Jan 1990 Nothin' To Hide Poco Jan 1990 Kickstart My Heart Motley Crue Jan 1990 I'll Be Good To You Quincy Jones f/ Ray Charles and Chaka Khan Feb 1990 Tender Lover Babyface Feb 1990 If You Leave Me Now Jaya Feb 1990 Was It Nothing At All Michael Damian Feb 1990 I Remember You Skid Row Feb 1990 Woman In Chains Tears For Fears Feb 1990 All Nite Entouch Feb 1990 Opposites Attract Paula Abdul w/ The Wild Pair Feb 1990 Walk On By Sybil Feb 1990 That's What I Like Jive Bunny & The Mastermixers Mar 1990 Summer Rain Belinda Carlisle Mar 1990 I'm Not Satisfied Fine Young Cannibals Mar 1990 Here We Are Gloria Estefan Mar 1990 Escapade Janet Jackson Mar 1990 Too Late To Say Goodbye Richard Marx Mar 1990 Dangerous Roxette Mar 1990 Sometimes She Cries Warrant Mar 1990 Price of Love Bad English Mar 1990 Dirty Deeds Joan Jett Mar 1990 Got To Have Your Love Mantronix Mar 1990 The Deeper The Love Whitesnake Mar 1990 Imagination Xymox Mar 1990 I Go To Extremes Billy Joel Mar 1990 Just A Friend Biz Markie Mar 1990 C'mon And Get My Love D-Mob Mar 1990 Anything I Want Kevin Paige Mar 1990 Black Velvet Alannah Myles Mar 1990 No Myth Michael Penn Mar 1990 Blue Sky Mine Midnight Oil Mar 1990 A Face In The Crowd Tom Petty Mar 1990 Living In Oblivion Anything Box Mar 1990 You're The Only Woman Brat Pack Mar 1990 Sacrifice Elton John Mar 1990 Fly High Michelle Enuff Z'Nuff Mar 1990 House of Broken Love Great White Mar 1990 All My Life Linda Ronstadt (f/ Aaron Neville) Mar 1990 True Blue Love Lou Gramm Mar 1990 Keep It Together Madonna Mar 1990 Hide and Seek Pajama Party Mar 1990 I Wish It Would Rain Down Phil Collins Mar 1990 Love Me For Life Stevie B. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

Examining the Role Hip-Hop Texts Play in Viewing the World

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Department of Middle-Secondary Education and Middle-Secondary Education and Instructional Instructional Technology (no new uploads as of Technology Dissertations Jan. 2015) Fall 1-10-2014 Wordsmith: Examining the role hip-hop texts play in viewing the world Crystal LaVoulle Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/msit_diss Recommended Citation LaVoulle, Crystal, "Wordsmith: Examining the role hip-hop texts play in viewing the world." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2014. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/msit_diss/119 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Middle-Secondary Education and Instructional Technology (no new uploads as of Jan. 2015) at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Middle-Secondary Education and Instructional Technology Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ACCEPTANCE This dissertation, WORDSMITH: EXAMINING THE ROLE HIP-HOP TEXTS PLAY IN VIEWING THE WORLD, by CRYSTAL LAVOULLE, was prepared under the direction of the candidate’s Dissertation Advisory Committee. It is accepted by the committee members in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Philosophy, in the College of Education, Georgia State University. The Dissertation Advisory Committee and the student’s Department Chairperson, as representatives of the faculty, certify that this dissertation has met all standards of excellence and scholarship as determined by the faculty. The Dean of the College of Education concurs. _________________________________ _________________________________ Peggy Albers, Ph.D. Tisha Y. Lewis, Ph.D. Committee Chair Committee Member _________________________________ _________________________________ Kimberly Glenn, Ph.D. -

“Thank You” Music Video by Mkto a Final Project

EXTENDED ESSAY OF THE CONFLICTS BETWEEN TWO GENERATIONS REFLECTED IN “THANK YOU” MUSIC VIDEO BY MKTO A FINAL PROJECT In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement For S-1 Degree in American Cultural Studies In English Department, Faculty of Humanities Diponegoro University Submitted by: Nissa Soraya 13020111130067 FACULTY OF HUMANITIES DIPONEGORO UNIVERSITY SEMARANG 2015 PRONOUNCEMENT I state truthfully that this project is compiled by me without taking the results from other research in any university, in S-1, S-2, and S-3 degree and diploma. In addition, I ensure that I do not take the materials from other publications or someone’s work except for the references mentioned in the references. Semarang, 14 November 2015 Nissa Soraya ii APPROVAL Approved by Advisor, Drs. Siswo Harsono, M. Hum. NIP. 19640418 199001 1 001 iii VALIDATION Approved by Strata I Final Project Examination Committee Faculty of Humanities Diponegoro University on January 2016 Chair Person First Member Arido Laksono, S.S, M. Hum. Sukarni Suryaningsih, S.S, M. Hum NIP. 19750711 199903 1 002 NIP. 19721223 199802 2 001 Second Member Third Member Prof. Dr. Nurdien H. Kistanto, M.A. Dra. Cut Aja Puan Ellisafni, M. Ed. NIP. 19521103 198012 1 001 NIP. 19551003 197812 2 001 iv MOTTO AND DEDICATION Hope. It is the only thing stronger than fear. A little hope is effective. A lot of hope is dangerous. A spark is fine, as long as it's contained. (The Hunger Games (2012)) Friendship is always a sweet responsibility, never an opportunity. (Kahlil Gibran) Instead of giving up before even trying, I plan on properly going through with it till the end. -

DJ Song List

978-256-1899 DJ Example List BY ARTIST Artist Title Disc Poloma Polka 203 A 03 Pennsylvania Polka 203 A 06 My Melody Of Love Polka 203 A 10 Mexican Hat Dance 201 B 07 La Raspa 201 B 01 Just Because 203 A 09 It’s A Small World Polka 203 A 08 Hava Nagila 202 A 04 Happy Birthday 202 A 01 Domino Polka 203 A 02 Clarinet Polka 203 A 07 Cherry Pink & Apple Blossom 201 B 02 Champaigne Polka 203 A 02 Bunny Hop 201 B 08 Beer Barrel Polka 203 A 05 Baruska 203 A 04 1 Giant Leap feat My Culture POct02-12 1. PlusWilliams 1 CherryMy Culture Bomb T552-11 1000 Clowns (Not The) Greatest Rapper T470-13 10,000 Maniacs More Than This T382-06 10,000 Maniacs More Than This RH 4312 10,000 Maniacs Rainy Day (Edit) T403-11 10,000 Maniacs Trouble Me 89 A 06 112 Come See Me T362-16 112 Cupid (Radio Mix) T376-08 112 Only You T330-15 112 Your Letter (Radio Mix) T491-08 112 It’s Over Now (Radio Edit) T563-09 112 Peaches & Cream PJuly01-17 112 (f/ Lil' Z) Anywhere (Radio Mix) T465-12 112 f/Mase Love Me (Radio Mix) T454-11 12 Volt Sex Hook It Up T557-14 15 Distracted T549-19 1910 Fruitgum Compa Simon Says 205 B 03 2 Elvissa Oh La La La (Radio Mix) T392-12 2 Live Crew Banned In The Sea 94 B 04 2 Pac Changes (Radio Edit) T459-10 2 Pac I Wonder If Heaven Got A Ghetto T408-13 2 Pac F/KC & Jo Jo How Do You Want It T334-14 2 Pistols f./T-Pain & Dizm She Got It *Promo Only Clean Edit* PFeb08-10 April 23, 2013 Page 1 2 Skinee J’s Grown Up PApril02-16 2 Unlimited Get Ready For This Dance Mix 4-14 2 Unlimited Tribal Dance Dance Mix USA 15 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone Dance Mix USA -

![Freewaves: KUCI 88.9 FM Spring [1983] Program Guide](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6097/freewaves-kuci-88-9-fm-spring-1983-program-guide-5206097.webp)

Freewaves: KUCI 88.9 FM Spring [1983] Program Guide

FREEWAVES-KUCI".9 FM SPRING PRDGRAMGUI,DE I T • · )ff!.~1~ I '-A~ '. ( ~ .' :<l~~~\" " o • k " ;: .,:i!)ir· ~ ' .' . ~11IJ,J ':;7 . .. ~..., . " .. .. ..,~..,. ' -.:, /;;,\;;;j!N;~\~;: . #,11;•• >. .. ~~: , g; .,;.. '. -' PhotobyDon In side: .. Exclusive psychedelic Furs Interview ' Bangles Interview . KUCI SpeciaJprogramming Music Genre Exploration ,Drangecounty's Finest Alternative '.~'. :. : ~.~" '~ Album Reviews NewMusic Tries loCapture Markel bands of the '80s. On Feline, the Strang MÙOD OF DEFIANCE - Now an L.P . tween comprehensibility and obscurity. Cover Deceiving, lers mix '80s synthetic technology with Early L.A. punk sound with a female sing The two songs I enjoyed most, "Molasses Music Average old world European romance, to come up er. "Giri in a Painting" and "Afternoon- . Run" and "Plaza Real," were written by with a distinct 'heavy metal meets My Garden" are great post-punk tunes, Zawinu!. I am disappointed in his compo Single Bullet Theory- psychedelia' fee!. The Stranglers are one similar to "Public Image" with Patti sitions on this album because I know he Single Bullet Theory (Nemperor) of the few bands who are able to deal Smith. (Underground Records) can turn out better stuff Ii.ke "Birdland." If Ali I can say is, I wish the music was as with heavy emotional or political themes you like electronic instruments, if you Iike good as the album cover. Emblazoned 'Nithout appearing word-heavy or mud DREAM SYNDICATE - "Days of Wine space sounds, if you dabble in the avant upon the cover are a dozen multi-colored dling through trite overworked Iyrics. and Roses." My favorite band of 1982,. garde, this album is for yOu. If you like water pistols.