Letter to Zinke May 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Utah Conservation Community Legislative Update

UTAH CONSERVATION COMMUNITY LEGISLATIVE UPDATE 2020 General Legislative Session Issue #5 March 1, 2020 Welcome to the 2020 Legislative Update issue will prepare you to call, email or tweet your legislators This issue includes highlights of week five, what we can with your opinions and concerns! expect in the week ahead, and information for protecting wildlife and the environment. Please direct any questions or ACTION ALERT! comments to Steve Erickson: [email protected]. The Inland Port Modifications bill - HB 347 (Rep. About the Legislative Update Gibson), is now awaiting action on the House floor, The Legislative Update is made possible by the Utah probably Monday but early in the week for sure. We’re Audubon Council and contributing organizations. Each working to get it amended as it moves forward, but it Update provides bill and budget item descriptions and will remain a bill for a project and process we can’t support. status updates throughout the Session, as well as important Session dates and key committees. For the most up-to-date Oppose HB 347! information and the names and contact information for all legislators, check the Legislature’s website at HB 233, the Depleted Uranium-funded Natural Resources Legacy Fund, will be debated and voted on in the Senate www.le.utah.gov. The Legislative Update focuses on this week. Urge legislators to pass the Fund without the legislative information pertaining to wildlife, sensitive and DE funding source- and avoid making this their legacy! invasive species, public lands, state parks, SITLA land management, energy development, renewable energy and Lastly, contact your legislators to urge them to fund bills and budgets to Clear the Air! conservation, and water issues. -

2021 State Legislator Pledge Signers

I pledge that, as a member of the state legislature, I will cosponsor, vote for, and defend the resolution applying for an Article V convention for the sole purpose of enacting term limits on Congress. The U.S. Term Limits Article V Pledge Signers 2021 State Legislators 1250 Connecticut Ave NW Suite 200 ALABAMA S022 David Livingston H073 Karen Mathiak Washington, D.C. 20036 Successfully passed a term S028 Kate Brophy McGee H097 Bonnie Rich (202) 261-3532 limits only resolution. H098 David Clark termlimits.org CALIFORNIA H103 Timothy Barr ALASKA H048 Blanca Rubio H104 Chuck Efstration H030 Ron Gillham H105 Donna McLeod COLORADO H110 Clint Crowe ARKANSAS H016 Andres Pico H119 Marcus Wiedower H024 Bruce Cozart H022 Margo Herzl H131 Beth Camp H042 Mark Perry H039 Mark Baisley H141 Dale Washburn H071 Joe Cloud H048 Tonya Van Beber H147 Heath Clark H049 Michael Lynch H151 Gerald Greene ARIZONA H060 Ron Hanks H157 Bill Werkheiser H001 Noel Campbell H062 Donald Valdez H161 Bill Hitchens H001 Judy Burges H063 Dan Woog H162 Carl Gilliard H001 Quang Nguyen H064 Richard Holtorf H164 Ron Stephens H002 Andrea Dalessandro S001 Jerry Sonnenberg H166 Jesse Petrea H002 Daniel Hernandez S010 Larry Liston H176 James Burchett H003 Alma Hernandez S023 Barbara Kirkmeyer H177 Dexter Sharper H005 Leo Biasiucci H179 Don Hogan H006 Walter Blackman CONNECTICUT S008 Russ Goodman H007 Arlando Teller H132 Brian Farnen S013 Carden Summers H008 David Cook H149 Kimberly Fiorello S017 Brian Strickland H011 Mark Finchem S021 Brandon Beach H012 Travis Grantham FLORIDA S027 Greg Dolezal H014 Gail Griffin Successfully passed a term S030 Mike Dugan H015 Steve Kaiser limits only resolution. -

Utah Conservation Community Legislative Update

UTAH CONSERVATION COMMUNITY LEGISLATIVE UPDATE 2020 General Legislative Session Issue #1 February 2, 2020 Welcome to the 2020 Legislative Update issue will prepare you to call, email or tweet your legislators This issue includes highlights of week one, what we can with your opinions and concerns! expect in the week ahead, and information for protecting wildlife and the environment. Please direct any questions or ACTION ALERT! comments to Steve Erickson: [email protected]. It’s an election year, and it appears that certain rural and About the Legislative Update trophy hunting interests and politics will attempt to wag The Legislative Update is made possible by the Utah the dog of the sixth most urbanized state yet again. HB Audubon Council and contributing organizations. Each 125 would require that the Director of the Division of Update provides bill and budget item descriptions and Wildlife Resources take immediate action to reduce predators if deer or elk herds dip below management status updates throughout the Session, as well as important objectives. Session dates and key committees. For the most up-to-date Also in the pipeline is HB 228, which would permit information and the names and contact information for all livestock owners to kill predators that harass, chase, legislators, check the Legislature’s website at disturb, harm, attack, or kill livestock on private lands or www.le.utah.gov. The Legislative Update focuses on public grazing allotments. Currently, livestock owners legislative information pertaining to wildlife, sensitive and are compensated for losses due to predation and request invasive species, public lands, state parks, SITLA land DWR remove or take offending predators. -

Utah Conservation Community Legislative Update

UTAH CONSERVATION COMMUNITY LEGISLATIVE UPDATE 2019 General Legislative Session Issue #3 February 18, 2019 Welcome to the 2019 Legislative Update issue will prepare you to call, email or tweet your legislators This issue includes highlights of week two, what we can with your opinions and concerns! expect in the week ahead, and information for protecting wildlife and the environment. Please direct any questions or ACTION ALERT! comments to Steve Erickson: [email protected]. SB 52 - Secondary Water Metering Requirements passed About the Legislative Update in committee and is headed for Senate floor votes soon . Contact Senators and urge them to support this critical The Legislative Update is made possible by the Utah water saving measure and the money that goes with it. Audubon Council and contributing organizations. Each SB 144 (see bill list below) would establish a baseline for Update provides bill and budget item descriptions and measuring the impacts of the Inland Port, and generate status updates throughout the Session, as well as important data that would inform environmental studies and policy Session dates and key committees. For the most up-to-date going forward. Let Senators know this is important! information and the names and contact information for all Public and media pressure the Governor’s efforts have legislators, check the Legislature’s website at forced needed changes to HB 220, but there’s still work www.le.utah.gov. The Legislative Update focuses on to do and it’s still a bad and unnecessary bill. Keep up the calls and emails to Senators and Governor Herbert! legislative information pertaining to wildlife, sensitive and And if you still have time and energy, weigh in on a invasive species, public lands, state parks, SITLA land priority for funding (see below) – or not funding! management, energy development, renewable energy and conservation, and water issues. -

The Utah Taxpayer

12 April 2013 Volume 38 Issue 4 THE UTAH TAXPAYER A Publication of the Utah Taxpayers Association Legislature Rejects Taxpayer Subsidies for a Convention Center Hotel April 2013 Volume 38 In the waning days of the General Session, your Taxpayers Association won one of the most heated legislative battles by defeating SB 267, sponsored by Senator Stuart Adams. Under this bill, Utah taxpayers would have had to Taxpayers Association subsidize a convention center hotel. Following a hard fought and healthy Releases 2013 Legislative legislative debate, the Senate narrowly approved the bill, but the House rejected it. Scorecard Page 2 Tourism and conventions improve Utah’s economy Utah is a destination tourist state. Our skiing is renowned the world over. My Corner: Utah Receives Temple Square, especially in the spring and at Christmas, is one of the most Only “A” Grade on Digital beautiful treasures in the country. And our national parks, state parks, monuments, etc. attract visitors from around the world. Learning Now Report Card Despite these wonderful attractions, Utah is not the destination of choice for Page 3 many national or international conventions. Orlando, Las Vegas, Dallas, Atlanta Taxpayers Association and the Washington D.C. metro area all tend to win convention business that Successful in 2013 Legislative Utah convention promoters covet. The reason Utah Assuming that Session wants these conventions is simple. Like tourists, this convention convention-goers stimulate Utah’s economy as they stay Page 4 center hotel would in hotels, eat at local restaurants, buy lift tickets, plus be such an the paraphernalia associated with vacations and The STEM Action Center: unmitigated conventions. -

United States Department of the Interior Montana March 9-12, 2017

United States Department of the Interior Official Travel Schedule of the Secretary Montana March 9-12, 2017 TRIP SUMMARY THE TRIP OF THE SECRETARY TO 1 Montana, Colorado March 9-March 12, 2017 Weather: Whitefish/Glacier Wintery Mix, High: 41ºF, Low: 26ºF / Snow, High: 21ºF, Low: 12ºF Missoula Cloudy, High: 45ºF, Low: 35ºF Time Zone: Montana Mountain Standard Time (-2 hours from DC) Advance (Glacier/Missoula): Cell Phone: Security Advance (b) (6), (b) (7)(C) Advance Rusty Roddy Advance Wadi Yakhour (b) (6) Traveling Staff: Agent in Charge (b) (6), (b) (7)(C) Press Secretary Heather Swift ## Photographer Tami Heilemann ## Attire: 2 Thursday, March 9, 2017 W ashing ton, D C → W hitefish, M T 2:45-3:15pm EST: Depart Department of the Interior en route National Airport Car: RZ 4:08pm EST- 6:15pm MST: Wheels up Washington, DC (DCA) en route Denver, CO (DEN) Flight: United Airlines 1532 Flight time: 4 hours, 7 minutes RZ Seat: 23C AiC: (b) (6), (b) (7)(C) Staff: Heather Swift, Tami Heilemann Wifi: NOTE: TIME ZONE CHANGE EST to MST (-2 hour change) 6:15-6:58pm MST: Layover in Denver, CO // 43 minute layover 6:58pm MST- 9:16pm MST: Wheels up Denver, CO (DEN) en route Kalispell, MT (FCA) Flight: United Airlines 5376 Flight time: 2 hours, 18 minutes RZ Seat: 3C AiC: (b) (6), (b) (7)(C) Staff: Heather Swift, Tami Heilemann Wifi: 9:16-9:30pm MST: Wheels down Glacier Park International Airport Location: 4170 US-2 Kalispell, MT 59901 9:30-9:50pm MST: Depart Airport en route RON Location: 409 2nd Street West Whitefish, MT 59937 Vehicle Manifest: Sec. -

House Members Tell KUTV How They Voted on Medicaid Expansion, Mostly

House members tell KUTV how they voted on Medicaid expansion, mostly BY CHRIS JONES TUESDAY OCTOBER 20TH 2015 Link: http://kutv.com/news/local/how-members-of-the-house-voted-on-medicaid-expansion-mostly Salt Lake City — (KUTV) Last Week After three years of debate, the final negotiated plan that could bring health care to nearly 125,000 poor Utahn's failed to pass out of the Republican controlled caucus At the time, Speaker of the House Greg Hughes along with other members of the house leadership, met with the media after the closed meeting. At the time, Hughes said he and Rep. Jim Dunnigan voted for the Utah Access Plus plan. A plan that had been negotiated with top Republican leaders. Reporters criticized the house leadership for holding the closed meeting and not allowing the public to hear the debate of leaders At the time Hughes suggested that reporters ask all the members of the 63 person caucus how they voted if they wanted to know exactly who voted for what "I don't think they're going to hide it. Ask em where they're at, I think they'll tell you where they are," said Hughes So that's what we did, we emailed and called every Republican lawmaker in the caucus to find out how they voted. We do know the proposal failed overwhelmingly, one lawmaker says the vote was 57-7. Here is what we found during our research: Voted NO Daniel McCay Voted YES Rich Cunningham Jake Anderegg Johnny Anderson Kraig Powell David Lifferth Raymond Ward Brad Daw Mike Noel Earl Tanner Kay Christofferson Kay McIff Greg Hughes Jon Stanard Brian Greene Mike -

Utah County Republican Party Who Should Attend Which Meetings?

Utah County Republican Party Nominating Convention 2018 Saturday, April 14, 2018 Timpview High School 3570 North 650 East Provo, Utah 84604 Schedule 7:00 am Check - In / Credentials Desk Open Activate phones and Test Vote 8:00 am Central Committee Meeting 9:00 am Convention General Session Senate District Elections (SD15) House District Elections and Meetings Reconvene for Countywide Races County Clerk/Auditor County Commissioner (Seat “A”) County Commissioner (Seat “B”) County Attorney Sheriff Who should attend which meetings? Central Committee Meeting - Members of the Central Committee consisting of all: Precinct Chairs, Precinct Vice Chairs; Legislative District Chairs, Vice Chairs, Education Officers; Steering Committee Members; Past County Party Chairs; Elected Officials residing in Utah County. Senate District Elections – All County Delegates from Senate District 15. Otherwise, please visit with the candidates in the exhibit hall. House District Caucuses – All County Delegates will meet in their House District. The following House Districts will have contested elections 6, 27, 57, 60, 61, 65 and 67. All other House Districts will have a caucus meeting and a legislative report. Convention General Session – All County Delegates and Central Committee members. Caucus Room Assignments Senate District Caucuses Senate District 15 (HDs 57, 59, 60, 61): Auditorium No Caucus for the following Senate Districts : Senate District 7 Senate District 11 Senate District 13 Senate District 14 Senate District 16 Senate District 24 Senate District -

Utah Conservation Community Legislative Update

UTAH CONSERVATION COMMUNITY LEGISLATIVE UPDATE 2017 General Legislative Session Issue #4 February 19, 2017 Welcome to the 2017 Legislative Update issue will prepare you to call, email or tweet your legislators This issue includes highlights of week four, what we can with your opinions and concerns! expect in the week ahead, and information for protecting wildlife and the environment. Please direct any questions or ACTION ALERT! comments to Steve Erickson: [email protected]. New bills emerged that deserve our support. See SB 214, About the Legislative Update SB 217 and SB 218 in the bills tracking list below. Two bad bills that escaped attention up until now are HB 280 The Legislative Update is made possible by the Utah and SB 189 (also below). Audubon Council and contributing organizations. Each Update provides bill and budget item descriptions and For Actions on the climate change resolution (SJR 9), HB status updates throughout the Session, as well as important 11, and on the inappropriate proposals endorsed by Session dates and key committees. For the most up-to-date NRAE Appropriations to fight all things federal, see information and the names and contact information for all below. legislators, check the Legislature’s website at www.le.utah.gov. The Legislative Update focuses on Calls/emails to members of the Executive Appropriations legislative information pertaining to wildlife, sensitive and Committees) will be needed throughout the remainder of invasive species, public lands, state parks, SITLA land the Session (see Budget News, below). management, energy development, renewable energy and conservation, and water issues. The Update will be distributed after each Friday of the Session. -

Utah League of Cities and Towns

UTAH LEAGUE OF CITIES AND TOWNS GENERAL LEGISLATIVE SESSION 2019 UTAH LEAGUE OF CITIES AND TOWNS GENERAL LEGISLATIVE SESSION 2 2019 ULCT Legislative Team Cameron Diehl, Executive Director [email protected] Cameron has worked for ULCT since starting as an intern in 2006, and even though he’s now the Head Honcho, he still has to take out the literal and metaphorical garbage. Rachel Otto, Director of Government Relations [email protected] Rachel joined ULCT in December of 2017. As the League’s Director of Government Relations, she manages the League’s legislative outreach and imagines what life would be like if there was such a thing as summer vacation. Roger Tew, Senior Policy Advisor [email protected] Roger has worked on the Hill for 41 sessions, more than half with ULCT. He specializes in public utilities, judicial issues, tax policy, and telecommuni- cations policy, and has amazing stories about every conceivable issue in local government. John Hiskey, Senior Policy Advisor [email protected] John knows way more than a thing or two about local government, having been in the business for 40 years. In addition to his expertise in economic development, he serves as ULCT’s liaison with law enforcement and coordinated our efforts on water policy. He’s also known to break into a Beatles song without warning. Wayne Bradshaw, Director of Policy [email protected] Wayne is the newest member of ULCT’s full-time staff and jumped in right before the session to direct our research and fiscal analysis efforts. He inexplicably enjoys complicated home improvement projects. -

Jordan Cove Energy Project Final Environmental Impact Statement

APPENDIX A Distribution List for the Notice of Availability Jordan Cove Energy Project Final EIS APPENDIX A DISTRIBUTION LIST FOR THE NOTICE OF AVAILABILITY Federal Government – Elected officials US Bureau of Indian Affairs, Northwest Regional Office, Regional Director, Stanley Speaks, OR U.S. Representative Greg Walden, OR US Bureau of Land Management, Branch Chief - U.S. Representative Kurt Schrader, OR Land, Minerals and Energy Resources, Lenore U.S. Representative Peter Defazio, OR Heppler, OR U.S. Representative Chris Stewart, UT US Bureau of Land Management, Land Realty U.S. Representative Rob Bishop, UT Specialist, Diann Rasmussen, OR U.S. Representative Doug Lamborn, CO US Bureau of Land Management, Medford District Planning and Environmental Coordinator, Miriam U.S. Representative Ed Perlmutter, CO Liberator, OR U.S. Representative Ken Buck, CO US Bureau of Land Management, Planning U.S. Representative Scott Tipton, CO Coordinator, Leslie A. Frewing, OR U.S. Senator Jeff Merkley, OR US Bureau of Land Management, Program Manager, U.S. Senator Ron Wyden, OR Cathy Harris, DC U.S. Senator Mike Lee, UT US Bureau of Reclamation, Realty Specialist, Lila Black, OR U.S. Senator Mitt Romney, UT US Coast Guard Sector North Bend, Commanding U.S. Senator Cory Gardner, CO Officer, Captain Michael T. Trimpert, OR U.S. Senator Michael Bennet, CO US Coast Guard, Captain of the Port, William U.S. Senator John Barrasso, WY Timmons, OR U.S. Senator Mike Enzi, WY US Coast Guard, Project Officer, Ken Lawrenson, U.S. Senator Lisa Murkowski, AK OR Federal -

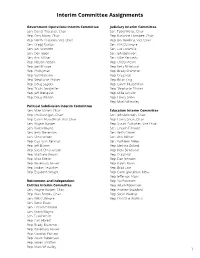

Interim Committee Assignments

Interim Committee Assignments Government Operations Interim Committee Judiciary Interim Committee Sen. Daniel Thatcher, Chair Sen. Todd Weiler, Chair Rep. Cory Maloy, Chair Rep. Karianne Lisonbee, Chair Rep. Norm Thurston, Vice Chair Rep. Jon Hawkins, Vice Chair Sen. Gregg Buxton Sen. Kirk Cullimore Sen. Jani Iwamoto Sen. Luz Escamilla Sen. Don Ipson Sen. John Johnson Sen. Ann Millner Sen. Mike Kennedy Rep. Nelson Abbott Rep. Cheryl Acton Rep. Joel Briscoe Rep. Kera Birkeland Rep. Phil Lyman Rep. Brady Brammer Rep. Val Peterson Rep. Craig Hall Rep. Stephanie Pitcher Rep. Brian King Rep. Doug Sagers Rep. Calvin Musselman Rep. Travis Seegmiller Rep. Stephanie Pitcher Rep. Jeff Stenquist Rep. Mike Schultz Rep. Doug Welton Rep. Lowry Snow Rep. Mark Wheatley Political Subdivision Interim Committee Sen. Mike McKell, Chair Education Interim Committee Rep. Jim Dunnigan, Chair Sen. John Johnson, Chair Rep. Calvin Musselman, Vice Chair Rep. Lowry Snow, Chair Sen. Wayne Harper Rep. Susan Pulsipher, Vice Chair Sen. Karen Mayne Sen. Lincoln Fillmore Sen. Jerry Stevenson Sen. Keith Grover Sen. Chris Wilson Sen. Ann Millner Rep. Gay Lynn Bennion Sen. Kathleen Riebe Rep. Jeff Burton Rep. Melissa Ballard Rep. Steve Christiansen Rep. Kera Birkeland Rep. Matthew Gwynn Rep. Craig Hall Rep. Mike Kohler Rep. Dan Johnson Rep. Rosemary Lesser Rep. Karen Kwan Rep. Jordan Teuscher Rep. Brad Last Rep. Elizabeth Weight Rep. Carol Spackman Moss Rep. Jefferson Moss Retirement and Independent Rep. Val Peterson Entities Interim Committee Rep. Adam Robertson Sen. Wayne Harper, Chair Rep. Andrew Stoddard Rep. Walt Brooks, Chair Rep. Steve Waldrip Sen. Kirk Cullimore Rep. Christine Watkins Sen. Gene Davis Sen.