University of Massachusetts Amherst Fifth-‐Year Interim Report to The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Institutional Self-Study September 2009

Institutional Self-Study September 2009 Submitted to the New England Association of Schools and Colleges Commission on Institutions of Higher Education Institutional Self-Study September 2009 Submitted to the New England Association of Schools and Colleges Commission on Institutions of Higher Education This publication in electronic format, with embedded online references, may be found at www.umass.edu/neasc by clicking “Self-Study.” A complete listing of URLs for those references, listed by Standard in order of appearance, may be found in the appendices to this report under “Document Library.” Questions or requests for additional information may be directed to the Self-Study chair: Bryan C. Harvey Associate Provost for Planning and Assessment University of Massachusetts 359 Whitmore Administration Building Amherst, MA 01003 [email protected] 413/545-2554 (Office) 413-559-8237 (Cell) TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTORY MATERIALS Institutional Characteristics i Introduction and Overview ix NARRATIVE Standard One: Mission and Purposes 1 Standard Two: Planning and Evaluation 4 Standard Three: Organization and Governance 16 Standard Four: The Academic Program 25 Standard Five: Faculty 52 Standard Six: Students 76 Standard Seven: Library and Other Information Resources 95 Standard Eight: Physical Resources 108 Standard Nine: Financial Resources 119 Standard Ten: Public Disclosure 129 Standard Eleven: Integrity 134 APPENDIX The Framework for Excellence Organizational Chart and UMass at a Glance 2008 Financial Report CIHE Data Forms Student Achievement and Success Forms Public Disclosure Form Document Library Institutional Characteristics This form is to be completed and placed at the beginning of the self-study report: Date: July 1, 2009 1. Corporate name of institution: University of Massachusetts Amherst 2. -

University of Massachusetts

UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS VOTES BOARD OF TRUSTEES SEPTEMBER 19, 2012 UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS BOARD OF TRUSTEES COMMITTEE: Administration and Finance – September 12, 2012 ACTION ITEM #b,1: University Capital Plan DATE: BoT – September 19, 2012 DOC. & VOTE I.D. #: T12-062 VOTED: Pursuant to Trustee policy T93-122, to approve the following capital projects identified in Appendix A of the University Capital Plan as described in Doc. T12-062: Projects for Board of Trustee Approval A. Projects New to the Capital Plan with activity to commence by FY14: Cost Estimate FY13-17 Campus Priority Project Name August 2012 Spending Amherst 36 Water tank repairs $1,000,000 $1,000,000 Amherst 41 Whitmore deferred maintenance $14,000,000 $14,000,000 Boston BI.03 Healey Building: Replace Plaza Level Waterproofing $4,000,000 $4,000,000 Boston BI.07 Clark Athletic Center Ice Rink: Replace Chiller Unit $1,000,000 $1,000,000 Boston BI.08 Clark Athletic Center: Repair South-facing Façade on Ice Rink facility $1,000,000 $1,000,000 Boston BI.14.02 Service and Supply Building: Install Fire Suppression System and Upgrade Fire Alarm System $2,300,000 $2,300,000 Dartmouth 7 Security Installation Project $7,000,000 $7,000,000 Lowell 18 Alumni Hall Renovations $5,000,000 $5,000,000 Lowell 20 Transportation & Parking Improvements $4,000,000 $4,000,000 Med School 9 Steam Chiller Replacement 3 $4,000,000 $4,000,000 Total of New Projects that will be Active in FY13 and FY14 $43,300,000 $43,300,000 B. -

Campus Chronicle April 25, 2003 3 Homeland Security Potential Assessed Daniel J

■ Science becomes art at polymer research center, page 4 Inside ■ Engineering students, professor restore historic bridges, page 7 The Campus Chronicle Vol. XVIII, No. 30 April 25, 2003 for the Amherst campus of the University of Massachusetts News Briefs House panel Open meetings set with dean candidate proposes The search committee for a new dean of the School of $78.9m cut Public Health and Health Sci- ences has scheduled several Daniel J. Fitzgibbons C open meetings next week HRONICLE STAFF with one of the candidates The University system could for the post, Steven Zeisel. lose $78.9 million in state funding Zeisel, who is associate next year under the $22.5 billion dean for research in the budget proposal unveiled Wed- school of public health at the nesday by House Ways and University of North Carolina, Means Committee Chairman John Chapel Hill, will participate in H. Rogers (D-Norwood). The House budget package an open meeting with faculty Eric M. Beekman Neil Immerman Max Page and staff on Thursday, May calls for cutting the five-campus 1, 3-4 p.m. in 165-169 Lin- system’s maintenance appropria- coln Campus Center. A ses- tion from $438,276,144 to sion for students will follow 3 awarded Guggenheim Fellowships $356,470,020 or 18 percent. Last year, the University re- at 4 p.m. in the same room. Barbara Pitoniak this outstanding achievement,” contributions to the study of ceived a maintenance appropria- On Friday, May 2, Zeisel NEWS OFFICE STAFF said Charlena Seymour, interim Dutch language and literature and tion of $445.6 million, but will make an academic pre- Three faculty members have senior vice chancellor for Aca- his efforts to promote an appre- subequent cuts ordered by the sentation, “Choline and brain been awarded fellowships from demic Affairs and provost. -

University of Massachusetts Building Authority Preliminary Official Statement Dated January 9, 2017

PRELIMINARY OFFICIAL STATEMENT DATED JANUARY 9, 2017 NEW ISSUES – BOOK-ENTRY ONLY Ratings: Fitch: “AA” Moody’s: “Aa2” S&P: “AA-” In the opinion of Mintz, Levin, Cohn, Ferris, Glovsky and Popeo, P.C., Bond Counsel, under existing law, assuming continued compliance with certain provisions of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended, interest on the Series 2017-1 Bonds and the Series 2017-3 Bonds (together, the “Tax Exempt Bonds”) will not be included in the gross income of holders of such Tax Exempt Bonds for federal income tax purposes. While interest on the Tax Exempt Bonds will not constitute a preference item for purposes of computation of the alternative minimum tax imposed on certain individuals and corporations, interest on the Tax Exempt Bonds will be included in “adjusted current earnings” of corporate holders of the Tax Exempt Bonds and therefore will be taken into account in computing the alternative minimum tax imposed on certain corporations. Interest on the Series 2017-2 Bonds will be included in the gross income of holders of such Bonds for federal income tax purposes. In the opinion of Bond Counsel, interest on the Bonds and any profit made on the sale thereof are exempt from Massachusetts personal income taxes, and the Bonds are exempt from Massachusetts personal property taxes. See “TAX MATTERS” herein. UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS BUILDING AUTHORITY R $166,225,000* $19,540,000* $166,495,000* Project Revenue Bonds Project Revenue Bonds Refunding Revenue Bonds Senior Series 2017-1 Senior Series 2017-2 (Federally Taxable) -

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs 100 Cambridge Street, Suite 900 Boston, MA 02114 Charles D

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs 100 Cambridge Street, Suite 900 Boston, MA 02114 Charles D. Baker GOVERNOR Tel: (617) 626-1000 Karyn E. Polito Fax: (617) 626-1081 LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR http://www.mass.gov/eea Kathleen A. Theoharides SECRETARY September 25, 2020 CERTIFICATE OF THE SECRETARY OF ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENTAL AFFAIRS ON THE NOTICE OF PROJECT CHANGE PROJECT NAME : University of Massachusetts Amherst 2012-2021 Capital Improvement Projects – Campus Pond Dredge Project PROJECT MUNICIPALITY : Amherst PROJECT WATERSHED : Connecticut EEA NUMBER : 15069 PROJECT PROPONENT : University of Massachusetts - Amherst DATE NOTICED IN MONITOR : August 26, 2020 Pursuant to the Massachusetts Environmental Policy Act (MEPA; M.G.L. c. 30, ss. 61-62I) and Section 11.10 of the MEPA regulations (301 CMR 11.00) as amended by a Special Review Procedure (SRP) dated June 22, 2012, I have reviewed the Notice of Project Change (NPC) and hereby determine that this project change does not require an Environmental Impact Report (EIR). As noted below, I am requiring the Proponent to consult with the MEPA Office regarding the need for an update on planning efforts and implementation of or modifications to the Campus Master Plan and implementation of future capital improvements projects at UMass Amherst. Original Project Description and Procedural History In June 22, 2012, Secretary Richard K. Sullivan established a Special Review Procedure (SPR) to guide MEPA review of future capital improvement projects at the University of Massachusetts Amherst Campus (UMass Amherst). The SRP required the submittal of an Expanded Environmental Notification Form (EENF) to describe projects planned for implementation within a ten-year planning horizon. -

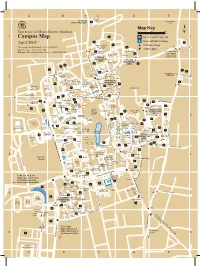

2009 CAMPUS MAP LAYERS 4-2009 UPDATED.Ai

Wysocki To Rt. 63N House 44 Renaissance North Village Apts Center Map Key 0 500 1,000 University of Massachusetts Amherst Feet Campus Map 44 31 Numbered Parking Lots 66 P Metered/Public Parking April 2009 24 Marks Meadow 44 PVTA Bus Stops University Switchboard - (413) 545-0111 Elementary 47 TILLSON ROAD School Tour Service - (413) 545-4237 Furcolo µ Traffic Lights 66 Montague McNamara To Tillson Farm & Robsham Memorial Visitors Center - (413) 545-0306 House North 47 Intermediate N North Processing O A Brown C Cashin RTH NORTH Facility (IPF) RESIDENTIAL PL SYLVAN E AREA A North North RESIDENTIAL S 27 B 44 A D AREA 68 NT 31 E DU S N TREE LA Totman N 26 MA 13 ST T A 24 43 E IVE DR Mobile To Mather, OLYMPIA DRIVE ORS Johnson VERN SPE, CO GO Computer Classrooms Dwight Science Leach Lewis µHamlin Engineering NORTHEAST Lab Astronomy Conte 24 Engineering Polymer RESIDENTIAL 45 Gunness Research LEDERLE Arnold 43 PVTA Lab 2 Duda AREA Auxiliary Center GRADUATE 43 Thatcher Bus Lyon T Services 65 RESEARCH H Observatory Garage CENTER Crabtree A Warehouse Marston T Robotics Knowlton C Marcus H Worcester E Thayer R Forest & Transit HO L Dining R D West 63 S Parks Bldg Facility 65 OAD W Paige Knowles Experiment East 65 O Goessmann R T Station Experiment H 65 W Station Holdsworth A 49 25 Y PARKING 49 ORCHARD HIL µ Bowditch 65 L DR. OFFICE Hatch Integrated 49 41 Agricultural Stockbridge Draper Grayson 49 (Bowker Aud) Science Bldg Engineering Dickinson 12 65 Chenoweth ORCHARD HILL 25 LINCOLN Chancellor's CAMPUS Hasbrouck 63 RESIDENTIAL Cold Flint CENTER -

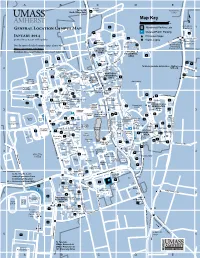

Map Key LOT 0 500 1,000 Feet

Wysocki To Rt. 63N, North Village Apts, House 44 Renaissance Agricultural Learning Center Center PURPLE Map Key LOT 0 500 1,000 Feet Amherst Fire 44 31 Numbered Parking Lots Department GENERAL LOCATION CAMPUS MAP P Metered/Public Parking 66 24 September 2018 44 PVTA Bus Stops TILLSON ROAD For the more detailed campus map, 47 Ó Traffic Lights Ó please visit: https://my.umass.edu/campusmap Furcolo UMass Police 66 Montague McNamara Campus Boundaries Department House North 47 To Tillson Farm Robsham Memorial Visitors Center - (413) 545-0306 N North & Intermediate O A Brown C Cashin RT NORTH Processing H RESIDENTIAL Facility (IPF) P SYLVAN L E AREA A North North RESIDENTIAL S 27 B 44 A D AREA 68 N T 31 E KS S N T A R L Totman N 26 E MA 13 E ST T A 24 43 E VE DRI To Mather, CO ORS Johnson VERN OLYMPIA DRIVE GO Computer Dwight Science Leach Lewis Hamlin For safe and convenient parking, it Engineering NORTHEAST Lab Astronomy Conte is essential that parking be controlled. 24 Engineering Polymer RESIDENTIAL Unless otherwise noted, posted tow 45 Gunness Research LEDERLE Arnold 43 PVTA Lab 2 Duda AREA zones are enforced by ticketing and Auxiliary Center GRADUATE 43 Thatcher Bus Lyon T towing 24 hours a day. Careful attention Services 65 RESEARCH H Observatory Garage CENTER A while parking your vehicle can prevent Warehouse Robotics Marston Crabtree T C it from being ticketed and towed. Marcus Knowlton H Physical Worcester E 65 R Forest & Transit HO Sciences Bldg L Dining R PURPLE D 63 S Parks Bldgs Facility 65 OAD W Paige Knowles Goessmann West 65 O LOTS R Experiment East T H Experiment W 65 Station Holdsworth A 49 25 Y Station PARKING 49 ORCHARD HIL Bowditch 65 L DR. -

The Campus Chronicle Nov. 15, 2002

■ ROTC cadets conduct exercises at West Point, page 4 Inside ■ Emergency closing and snow parking information, page 6 The Campus Chronicle Vol.XVIII, No. 12 November 15, 2002 for the Amherst campus of the University of Massachusetts News Briefs Library offers around Lecture examines immigration and the clock reference help economic policy Emily Silverman Northeastern University, Tufts A free public lecture, “Im- SPECIAL TO THE CHRONICLE University, University of Con- migration Policy and the necticut, University of New American Economy,” by It’s 2 a.m., the Library’s closed George Borjas, Robert W. and a weary undergraduate needs Hampshire, and Williams College. Scrivner Professor of Eco- some research assistance for a pa- The BLC ASK 24/7 service is nomics and Social Policy at per that’s due in a few hours. But staffed by professional reference the John F. Kennedy School there’s no need to panic — help is librarians located in the BLC mem- of Government at Harvard just a mouse click away through a ber libraries and by professional University, is scheduled for new collaboration between 10 reference librarians from around Thursday, Nov. 21 at 4 p.m. New England colleges and univer- the world. Librarians from the BLC in Memorial Hall. sities. participating libraries will cover Borjas’ research on immi- Starting this week, the campus the BLC ASK 24/7 service week- gration’s economic impact is days from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. widely considered to play a Library system began offering The live reference service of- central role in national and in- professional librarian reference as- ternational discussions about sistance 24 hours a day, seven fers an educational alternative to immigration policy, according days a week in real time via the the Web search engines used by to John Hird, director of the World Wide Web. -

Map Key General Location Campus

Wysocki To Rt. 63N House 44 Renaissance North Village Apts Center Map Key 0 500 1,000 Feet Amherst Fire 44 General Location Campus Map 31 Numbered Parking Lots Department 66 P Metered/Public Parking 24 January 2014 44 PVTA Bus Stops 47 TILLSON ROAD printed twice a year with updates Furcolo Traffic Lights UMass Police 66 Montague McNamara To Tillson Farm & House Department North 47 Intermediate For the more detailed campus map, please visit: NORTH PLEASANT STREET North A Brown Processing C Cashin https://go.umass.edu/map/ NORTH Facility (IPF) RESIDENTIAL Robsham Memorial Visitors Center - (413) 545-0306 AREA SYLVAN North North RESIDENTIAL 27 D B AREA 44 68 31 E DU N LA 26 Totman AN TM 13 AS 24 43 E VE DRI To Undergraduate Admissions - Mather, ORS Johnson VERN SPE, CO OLYMPIA DRIVE GO Computer Dwight Science Leach Lewis Hamlin Engineering NORTHEAST Lab Astronomy Conte 24 Engineering Polymer RESIDENTIAL 45 Gunness Research LEDERLE Arnold 43 PVTA Lab 2 Duda AREA Auxiliary Center GRADUATE 43 Thatcher Bus Lyon T Services 65 RESEARCH H Observatory Garage CENTER Crabtree A Warehouse Marston T Robotics Knowlton C Marcus H Worcester E Thayer R Forest & Transit HO L Dining R D West 63 S Parks Bldg Facility 65 OAD W Paige Knowles Experiment East 65 O Goessmann R T Station Experiment H 65 W Station Holdsworth A 49 25 Y PARKING 49 ORCHARD HIL Bowditch 65 L DR. OFFICE Hatch Integrated Stockbridge 49 41 Agricultural Draper Science Bldg Grayson 49 Bowditch (Bowker Aud) Engineering Dickinson 12 Greenhouses 65 Chenoweth Life ORCHARD HILL 25 LINCOLN Science Lab. -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 446 613 HE 033 454 TITLE University of Massachusetts Amherst Factbook, 1996-1998. INSTITUTION Massachusetts Univ., Amherst. Office of Institutional Research. PUB DATE 1998-00-00 NOTE 91p. AVAILABLE FROM Univ. of Massachusetts Amherst, Office of Institutional Research, 237 Whitmore, Amherst, MA 01003. Tel: 413-545-0941; e-mail: [email protected]. PUB TYPE Numerical/Quantitative Data (110)-- Reports - Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Higher Education; *Institutional Characteristics; School Demography; *School Statistics; State Universities; Tables (Data) IDENTIFIERS *University of Massachusetts Amherst ABSTRACT This factbook is a retrospective of the University of Massachusetts Amherst from 1996 through 1998 and includes many data tables and figures. It provides answers to many of the most commonly asked questions about the campus and serves as a source of comparative information over time. Detailed information is provided in the following categories: organization, admissions, enrollment, student statistics, degrees, faculty and staff, finances, and miscellaneous.(EV) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Office of Educational Research and Improvement PERMISSION TO REPRODUCE AND EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION DISSEMINATE THIS MATERIAL HAS CENTER (ERIC) his document has been reproduced as BEEN GRANTED BY received from the person or organization originating it. 0 Minor changes have been made to improve reproduction quality. Points of view or opinions stated in this TO THE EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES document do not necessarily represent INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) official OERI position or policy. 1 et a a BEST COPYAVAILABLE] 2 Preface The 1996-98 Factbook represents a asked questions about the campus needs or requests for more up-to- continuing effort to improve the and serves as a source of com- date information are encouraged quality and accessibility of infor- parative information over time. -

CNS Buildings and Research Centers

Buildings and Research Centers College of Natural Sciences, University of Massachusetts Amherst The College of Natural Sciences (CNS) at the University of Massachusetts consists of 13 departments and two schools: Astronomy, Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Biology, Chemistry, Environmental Conservation, Food Science, Geosciences, Mathematics and Statistics, Microbiology, Physics, Polymer Science and Engineering, Psychological and Brain Sciences, School of Earth and Sustainability, Stockbridge School of Agriculture, and Veterinary and Animal Sciences. The main UMass Amherst campus is located on 1,450 acres. The College of Natural Sciences (CNS) is housed in 18 buildings on the main campus (see attached map). These 18 buildings on the main campus are the primary sites for the academic and translation science work being done in CNS by faculty, postdoctoral students, graduate students, and undergraduates. They include research labs, classroom spaces, technology laboratories, and other research sites for faculty, students, and staff. Students and faculty also have access to other non-science buildings on campus including the athletic center, library, tennis courts, gymnasiums, track facilities, walking and biking trails, outdoor sports fields, and off-campus research centers. Off campus, CNS also operates a number of orchards, agricultural sites, a turf facility, the Hodgkins Cove Marine Station, the Cranberry Experiment Station, and more than 2,000 acres in five forests across the state. Recently completed projects include the creation of the Integrated Sciences Building and the Life Sciences Laboratory, which has been awarded LEED gold certification. Paige Lab received a complete building renovation and we’ve just completed a major renovation of space in Morrill Laboratory to house our Plant Biology Program. -

CAMIS List of Facilities

CAMIS List of Buildings Org Id Agency Site Site Name Building Building Name Mun Zone Zip Code County Sqr Feet 810 SHERIFF'S DEPARTMENT WORCESTER SDW00 SHERIFF'S DEPT-WORCESTER-W BOYLSTON 322SDW1200 EMERGENCY RESPONSE BUILDING WE BOYLSTO - - - 107 INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY DIVISION ITD00 ITD DATA CENTER AT SPRINGFIELD 268ITD1200 ITD DATA CENTER -- SPRINGFIELD SPRINGFIEL - HAMPDEN 146,984 508 GREENFIELD COMMUNITY COLLEGE GCC00 GREENFIELD COMMUNITY COLLEGE 164GCC1000 GREENHOUSE GREENFIELD 01301 FRANKLIN 522 512 UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AT LOWELL LOW02 UMASS LOWELL LOWELL 408LOW1000 HEALTH & SOCIAL SCIENCES BUILDING - 01854 MIDDLESEX - 512 UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AT LOWELL LOW02 UMASS LOWELL LOWELL 408LOW1201 AIKEN STREET RESIDENTIAL HALL LOWELL - - - 512 UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AT LOWELL LOW02 UMASS LOWELL LOWELL 408LOW1202 NORTH CAMPUS PARKING GARAGE - - - - 523 MASSACHUSETTS COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS NAC00 MASS COLLEGE OF LIBERAL ARTS 103NAC1200 CENTER FOR SCIENCE AND INNOVATION NO ADAMS 01247 BERKSHIRE 67,000 526 NORTHERN ESSEX COMMUNITY COLLEGE NEC01 NORTHERN ESSEX COMM COL LAWRENCE 515NEC1101 NEW ALLIED HEALTH BUILDING LAWRENCE 01840 ESSEX 43,175 543 SALEM STATE COLLEGE SSA00 SALEM STATE UNIVERSITY 531SSC1011 LIBRARY AND LEARNING COMMONS SALEM 01970 ESSEX - 550 UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AT AMHERST UMA00 UMASS - AMHERST 207UMA1102 NEW LABORATORY AND SCIENCE BUILDING AMHERST 01003 - 310,000 550 UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AT AMHERST UMA00 UMASS - AMHERST 207UMA1103 NEW ACADEMIC AND CLASSROOM BUILDING AMHERST 01003 - 172,875 560 UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AT BOSTON UMB00 UMASS BOSTON 551UMB1101 INTEGRATED SCIENCE COMPLEX - 02125 SUFFOLK - 601 TRIAL COURT TRC95 SALEM COURT COMPLEX 531TRC1001 J. MICHAEL RUANE JUDICIAL CENTER SALEM 01970 ESSEX 254,229 606 TRIAL COURT TRC26 GREENFIELD TRIAL COURT 164TRC1200 GREENFIELD TRIAL COURT - NEW FAC.