SPRING 2010 Literary Magazine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CITY LIGHTS PUBLISHERS CELEBRATING 60 YEARS 1955-2015 261 Columbus Ave | San Francisco, CA 94133

CITY LIGHTS PUBLISHERS CELEBRATING 60 YEARS 1955-2015 261 Columbus Ave | San Francisco, CA 94133 Juan Felipe Herrera has been appointed the 21st Poet Laureate of the United States for 2015-2016! Forthcoming from City Lights this September will be Herrera’s new collection of poems titled Notes on the Assemblage. Herrera, who succeeds Charles Wright as Poet Laureate, said of the appointment, “This is a mega-honor for me, for my family and my parents who came up north before and after the Mexican Revolution of 1910—the honor is bigger than me. I want to take everything I have in me, weave it, merge it with the beauty that is in the Library of Congress, all the resources, the guidance of the staff and departments, and launch it with the heart-shaped dreams of the people. It is a miracle of many of us coming together.” Herrera joins a long line of distinguished poets who have served in the position, including Natasha Trethewey, Philip Levine, W. S. Merwin, Kay Ryan, Charles Simic, Donald Hall, Ted Kooser, Louise Glück, Billy Collins, Stanley Kunitz, Robert Pinsky, Robert Hass and Rita Dove. The new Poet Laureate is the author of 28 books of poetry, novels for young adults and collections for children, most recently Portraits of Hispanic American Heroes (2014), a picture book showcasing inspirational Hispanic and Latino Americans. His most recent book of poems is Senegal Taxi (2013). A new book of poems from Juan Felipe Herrera titled Notes on the Assemblage is forthcoming from City Lights Publishers in September 2015. -

The Sigma Tau Delta Review

The Sigma Tau Delta Review Journal of Critical Writing Sigma Tau Delta International English Honor Society Volume 11, 2014 Editor of Publications: Karlyn Crowley Associate Editors: Rachel Gintner Kacie Grossmeier Anna Miller Production Editor: Rachel Gintner St. Norbert College De Pere, Wisconsin Honor Members of Sigma Tau Delta Chris Abani Katja Esson Erin McGraw Kim Addonizio Mari Evans Marion Montgomery Edward Albee Anne Fadiman Kyoko Mori Julia Alvarez Philip José Farmer Scott Morris Rudolfo A. Anaya Robert Flynn Azar Nafisi Saul Bellow Shelby Foote Howard Nemerov John Berendt H.E. Francis Naomi Shihab Nye Robert Bly Alexandra Fuller Sharon Olds Vance Bourjaily Neil Gaiman Walter J. Ong, S.J. Cleanth Brooks Charles Ghigna Suzan-Lori Parks Gwendolyn Brooks Nikki Giovanni Laurence Perrine Lorene Cary Donald Hall Michael Perry Judith Ortiz Cofer Robert Hass David Rakoff Henri Cole Frank Herbert Henry Regnery Billy Collins Peter Hessler Richard Rodriguez Pat Conroy Andrew Hudgins Kay Ryan Bernard Cooper William Bradford Huie Mark Salzman Judith Crist E. Nelson James Sir Stephen Spender Jim Daniels X.J. Kennedy William Stafford James Dickey Jamaica Kincaid Lucien Stryk Mark Doty Ted Kooser Amy Tan Ellen Douglas Ursula K. Le Guin Sarah Vowell Richard Eberhart Li-Young Lee Eudora Welty Timothy Egan Valerie Martin Jessamyn West Dave Eggers David McCullough Jacqueline Woodson Delta Award Recipients Richard Cloyed Elizabeth Holtze Elva Bell McLin Sue Yost Beth DeMeo Elaine Hughes Isabel Sparks Bob Halli E. Nelson James Kevin Stemmler Copyright © 2014 by Sigma Tau Delta All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Sigma Tau Delta, Inc., the International English Honor Society, William C. -

A New Selected Poetry Galway Kinnell • 811.54 KI Behind My Eyes

Poetry.A selection of poetry titles from the library’s collection, in celebration of National Poetry Month in April. ** indicates that the author is a United States Poet Laureate. A New Selected Poetry ** The Collected Poems of ** The Complete Poems, Galway Kinnell • 811.54 KI Robert Lowell 1927-1979 Robert Lowell; edited by Frank Elizabeth Bishop • 811.54 BI Behind My Eyes Bidart and David Gewanter • Li-Young Lee • 811.54 LE 811.52 LO The Complete Poems William Blake • 821 BL ** The Best Of It: New and ** The Collected Poems of Selected Poems William Carlos Williams The Complete Poems Kay Ryan • 811.54 RY Edited by A. Walton Litz and Walt Whitman • 811 WH Christopher MacGowan • The Best of Ogden Nash 811 WI The Complete Poems of Edited by Linell Nash Smith • Emily Dickinson 811.52 NA The Complete Collected Poems Edited by Thomas H. Johnson • of Maya Angelou 811.54 DI The Collected Poems of Maya Angelou • 811.54 AN Langston Hughes The Complete Poems of Arnold Rampersad, editor; David Complete Poems, 1904-1962 John Keats Roessel, associate editor • E.E. Cummings; edited by John Keats • 821.7 KE 811.52 HU George J. Firmage • 811.52 CU E.E. Cummings Elizabeth Bishop William Blake Emily Dickinson Ocean City Free Public Library 1735 Simpson Avenue • Ocean City, NJ • 08226 609-399-2434 • www.oceancitylibrary.org Natasha Trethewey Pablo Neruda Robert Frost W.B. Yeats Louise Glück The Essential Haiku: Versions of Plath: Poems ** Selected Poems Basho, Buson, and Issa Sylvia Plath, selected by Diane Mark Strand • 811.54 ST Edited and with verse translations Wood by Robert Hass • 895.6 HA Middlebrook • 811.54 PL Selected Poems James Tate • 811.54 TA The Essential Rumi The Poetry of Pablo Neruda Translated by Coleman Barks, Edited and with an introduction Selected Poems with John Moyne, A.A. -

Mountainside Teen's Short Film Wins Skintimate Contest Kilkenny

A WATCHUNG COMMUNICATIONS, INC. PUBLICATION The Westfield Leader and The Scotch Plains – Fanwood TIMES Thursday, October 7, 2010 Page 19 Metropolitan Opera’s Live HD Simulcasts Begin Fifth Season By GREG WAXBERG Alagna in the title role, conducted by Specially Written for The Westfield Leader and The Times Yannick Nézet-Séguin. WESTFIELD — This Saturday, The To commemorate the 100th anniver- Metropolitan Opera begins its fifth sea- sary of the opera’s world premiere at son of “The Met: Live in HD,” an the Met, the company is reviving Emmy- and Peabody Award-winning Giacomo Puccini’s La Fanciulla del series of Saturday matinee perfor- West this season, and it will be simul- mances simulcast live in high defini- cast on January 8 at 1 p.m. The cast tion to movie theaters around the world. includes Deborah Voigt as Minnie, with Select theaters will also show encore Nicola Luisotti conducting. presentations at 6:30 p.m. on the third John Adams conducts the Met’s pre- Wednesday after the live performances, miere production of his first opera, and PBS televises the simulcasts on Nixon in China, on February 12 at 1 “Great Performances at the Met.” p.m. In the cast are James Maddalena, These simulcasts capture onstage Janis Kelly and Kathleen Kim. action and the orchestra by using close- Susan Graham and Plácido Domingo up shots taken from many perspec- headline the cast of Christoph Willibald tives. During intermissions, the series von Gluck’s Iphigénie en Tauride on offers behind-the-scenes features, live February 26 at 1 p.m. -

Advanced Poetry Workshop Office LA 211 Fall 2016 [email protected] Tuesday, LA 233 3:30Pm-6:20Pm Office Hours: Wed

Prageeta Sharma – Advanced Poetry Workshop Office LA 211 Fall 2016 [email protected] Tuesday, LA 233 3:30pm-6:20pm Office hours: Wed. 3:00-5:30 411 POETRY WORKSHOP This is an advanced poetry workshop were we—as a class—will mindfully engage with the craft of poetry writing. Our primary text, The Penguin Anthology of Twentieth Century American Poetry, will allow us to focus on an expansive collection of poems that illustrate the uses of diction, syntax, recitation, and styles in 20th and 21st century poetry. Our supplemental link (below), Handbook of Poetic Forms, will help us to define and utilize poetic forms and tropes. We will also discuss current trends and themes in contemporary poetry today; in doing so, we will also trace the literary traditions that inform contemporary poetry. You will be required to explore poetic imitations and present your work and the work of published poets to the class; you will also be expected to keep a poetry journal in which you will reflect on assigned readings, create drafts and finished poems of your own, and collect poems, epigraphs, and images that will be of inspiration to you. This will be passed in as a midterm project. You will also be expected to complete poetry responses (2 pgs in journal), imitations, and poems (which I hope will be started and completed in your journal) and a poetry portfolio, which will be due at the end of the semester. REQUIRED READING: The Penguin Anthology of Twentieth Century American Poetry, Edited by Rita Dove Handbook of Poetic Forms, Ron Padgett http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED304701.pdf (link to PDF) Buy a journal or keep a computer journal that you will submit or print out to me for a midterm; it will also include poems. -

LIBRARY of CONGRESS MAGAZINE MARCH/APRIL 2015 Poetry Nation

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MAGAZINE MARCH/APRIL 2015 poetry nation INSIDE Rosa Parks and the Struggle for Justice A Powerful Poem of Racial Violence PLUS Walt Whitman’s Words American Women Poets How to Read a Poem WWW.LOC.GOV In This Issue MARCH/APRIL 2015 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS MAGAZINE FEATURES Library of Congress Magazine Vol. 4 No. 2: March/April 2015 Mission of the Library of Congress The Power of a Poem 8 Billie Holiday’s powerful ballad about racial violence, “Strange Fruit,” The mission of the Library is to support the was written by a poet whose works are preserved at the Library. Congress in fulfilling its constitutional duties and to further the progress of knowledge and creativity for the benefit of the American people. National Poets 10 For nearly 80 years the Library has called on prominent poets to help Library of Congress Magazine is issued promote poetry. bimonthly by the Office of Communications of the Library of Congress and distributed free of charge to publicly supported libraries and Beyond the Bus 16 The Rosa Parks Collection at the Library sheds new light on the research institutions, donors, academic libraries, learned societies and allied organizations in remarkable life of the renowned civil rights activist. 6 the United States. Research institutions and Walt Whitman educational organizations in other countries may arrange to receive Library of Congress Magazine on an exchange basis by applying in writing to the Library’s Director for Acquisitions and Bibliographic Access, 101 Independence Ave. S.E., Washington DC 20540-4100. LCM is also available on the web at www.loc.gov/lcm. -

“A Poet Is, Before Anything Else, a Person Who Is Passionately in Love with Language.” ― W.H

1 PRELIMINARY SYLLABUS The Making of a Poem: From Beginning to End (POET 16) Instructor: Kimberly Grey Fall 2014 “A poet is, before anything else, a person who is passionately in love with language.” ― W.H. Auden Welcome to The Making of a Poem! Grading You have three options: 1) No Grade Requested (this is the default option) 2) Credit/No Credit: Your attendance will determine your grade. 3) Letter Grade: Your attendance, participation, and submitted poems will account for 100% of your grade. Over the course of the quarter you should plan to turn in 2-3 poems for workshop. Course Work Reading: Over the span of 10 weeks, students will read a wide variety of poems and essays pertaining to craft and participate in lively discussions on the assigned text. Students should expect to read approximately one short essay and 6-8 poems a week. Writing Students will have the opportunity to turn in 2-3 poems for workshop. New work will be generated by in-class exercises and assigned prompts. Most writing will be done outside of the classroom, with class time used for discussion and workshop. Students should come prepared each week with pen and paper and the two required texts. By the end of the course, students should have completed a portfolio of approximately 6 poems and 3 revisions. Workshop A writing workshop is meant to support one another’s efforts with positive and critical feedback. Students will gain knowledge about their own work by listening to feedback and through their own careful consideration of the work of others. -

Beyond Poet Voice: Sampling the (Non-) Performance Styles of 100 American Poets

Beyond Poet Voice: Sampling the (Non-) Performance Styles of 100 American Poets Marit J. MacArthur, Georgia Zellou, and Lee M. Miller 04.18.18 Peer-Reviewed By: Jason Camlot & Anon. Clusters: Sound Article DOI: 10.22148/16.022 Dataverse DOI: 10.7910/DVN/FGNBHX Journal ISSN: 2371-4549 Cite: Marit J. MacArthur, Georgia Zellou, and Lee M. Miller, “Beyond Poet Voice: Sampling the (Non-) Performance Styles of 100 American Poets,”Cultural Analytics April 18, 2018. DOI: 10.22148/16.022. Literary readings provoke strong feelings, which feed intense critical de- bates.1And while recorded literary readings have long been available for study, 1This research was supported by a 2015-16 ACLS Digital Innovations Fellowship at the Univer- sity of California, Davis, and a grant from the Research Council of the University at California State University, Bakersfield in 2017, and it continues in 2018 with a NEH Digital Humanities Advance- ment grant (see http://textinperformance.soc.northwestern.edu/). Thanks to Hideki Kawahara for generously sharing TANDEM-STRAIGHT, to Dan Ellis for helping us set up his pitch-tracking al- gorithm in Matlab, to Robert Ochshorn and Max Hawkins for their development of the invaluable tools of Gentle and Drift that allowed much of the initial research to be undertaken, to the ModLab and the Digital Scholarship Lab at the University of California, Davis, and to undergraduate research assistants Pavel Kuzkin and Richard Kim at UC Davis and Mateo Lara and David Stanley at CSU Bakersfield. Thanks also to Steve McLaughlin, Steve Evans, Christopher Grobe, and Mark Liberman for useful advice, and to the helpful audiences in Stanford’s Material Imagination: Sound, Space and Human Consciousness workshop series and at Cultural Analytics 2017 at the University of Notre Dame, where some of this research was presented. -

The Cambridge Companion to Twenty-First-Century American Poetry Edited by Timothy Yu Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-48209-7 — The Cambridge Companion to Twenty-First-Century American Poetry Edited by Timothy Yu Frontmatter More Information the cambridge companion to twenty-first-century american poetry This Companion shows that American poetry of the twenty-first-century, while having important continuities with the poetry of the previous century, takes place in new modes and contexts that require new critical paradigms. Offering a comprehensive introduction to studying the poetry of the new century, this collection highlights the new, multiple centers of gravity that characterize American poetry today. Chapters on African American, Asian American, Latinx, and Indigenous poetries respond to the centrality of issues of race and indigeneity in contemporary American discourse. Other chapters explore poetry and feminism, poetry and disability, and queer poetics. The environment, capit- alism, and war emerge as poetic preoccupations, alongside a range of styles from the spoken word to the avant-garde, and an examination of poetry’s place in the creative writing era. Timothy Yu is the author of Race and the Avant-Garde: Experimental and Asian American Poetry since 1965, the editor of Nests and Strangers: On Asian American Women Poets, and the author of a poetry collection, 100 Chinese Silences. He is Martha Meier Renk-Bascom Professor of Poetry and Professor of English and Asian American Studies at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University -

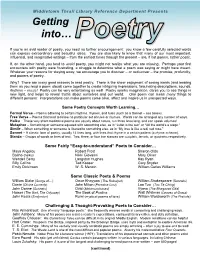

Getting Into Poetry

Middletown Thrall Library Reference Department Presents Getting into… If you’re an avid reader of poetry, you need no further encouragement: you know a few carefully selected words can express extraordinary and beautiful ideas. You are also likely to know that many of our most important, influential, and imaginative writings – from the earliest times through the present – are, if not poems, rather poetic. If, on the other hand, you tend to avoid poetry, you might not realize what you are missing. Perhaps your first encounters with poetry were frustrating, a struggle to determine what a poem was saying or might have meant. Whatever your reasons for staying away, we encourage you to discover – or rediscover – the promise, profundity, and powers of poetry. Why? There are many good reasons to read poetry. There is the sheer enjoyment of seeing words (and hearing them as you read a poem aloud) come together to create intriguing impressions, fascinating descriptions, sounds, rhythms – music! Poetry can be very entertaining as well! Poetry sparks imagination, dares you to see things in new light, and helps to reveal truths about ourselves and our world. One poem can mean many things to different persons: interpretations can make poems come alive, affect and inspire us in unexpected ways. Some Poetry Concepts Worth Learning… Formal Verse – Poems adhering to certain rhythms, rhymes, and rules (such as a Sonnet – see below). Free Verse – Poems that tend to follow no particular set of rules or rhymes. Words can be arranged any number of ways. Haiku – These very short meditative poems are usually about nature, run three lines long, and can speak volumes! Metaphor – Something or someone equated with something else, as in “Juliet is the sun” or “All the world’s a stage.” Simile – When something or someone is likened to something else, as in “My love is like a red, red rose.” Sonnet – A classic form of poetry, usually 14 lines long, with lines that rhyme in a certain pattern (a rhyme scheme). -

SPC's Annual Writers' Conference

SPC’s Annual Writers’ Conference Saturday, April 25 8:30 am – 4pm $40 for the day Casual lunch included register by emailing [email protected] Conference Schedule – see details on the following pages 8:30 – 9:00 Registration Gathering, Greeting & Coffee 9:00 – 10:25 Sarah Green Balancing Voice and Image 9:00 – 10:25 Kate Asche Lectio Divina – Reading into Writing(all genres) 10:30 – 11:55 Peter Campion Lyric Energy 10:30 – 11:55 Susan Gubernat You (Understood) 12:00 – 12:55 Lunch 1:00 – 2:30 Alan Soldofsky Setting Loose the Iambs: The Music of Free Verse 1:00 – 2:30 Julie Bruck Balancing Voice and Image 2:45 – 4:00 All Reception and Reading SPC’s Annual Writers’ Conference - April 25, 2015 - register: [email protected] Workshop: BALANCING VOICE AND IMAGE Frank O’Hara vs. William Carlos Williams; Gwendolyn Brooks vs. Kay Ryan; we often think of voice and image as all-or-nothing traits in poetry. A poem is driven either by personality or meditation. What happens, though, if we challenge our poems to achieve the inclusion of both an engaging, idiosyncratic speaker and striking, visual language? We’ll consider examples and try our hand at drafts in which voice and vision overlap and thrive. Sarah Green, a 2014 Rona Jaffe Foundation writing award nominee, most recently appeared in Best New Poets 2012 and the Incredible Sestina Anthology. A Pushcart Prize winner, she has been a semi-finalist for the Discovery prize, Crab Orchard’s first book prize, Barrow Street’s first book prize, the Ruth Lilly Poetry Fellowship, and the Walt Whitman Award. -

The Threepenny Review (ISSN 0275-1410)

165 SPRING 2021 SEVEN DOLLARS A Symposium on Rhyme and Repetition, with Commentary by Mark Morris, W. S. Di Piero, Ellen Pinsky, Nate Klug, Ethan Iverson, Rosanna Warren, and Mark Padmore Brenda Wineapple on Diane Johnson Javier Marías: Ridiculous Men Poems by Louise Glück, Jim Powell, Charles Simic, Adam Zagajewski, and others Ross Feld: Doing It Over David Hollander Watches Television Photographs by Arno Rafael Minkkinen © Copyright 2021 by The Threepenny Review (ISSN 0275-1410). All rights reserved. The Threepenny Review is published quarterly by The Threepenny Review (a Volume XLII, Number 1. Periodicals postage paid at Berkeley, California, and at nonprofit corporation) at 2163 Vine Street, Berkeley, California 94709. additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Please send address changes to Subscriptions cost $25.00 per year or $45.00 for two years (foreign rate: $50 The Threepenny Review, P.O. Box 9131, Berkeley, California 94709. per year). All mail, including subscription requests, manuscripts, and queries of any kind, should be sent to The Threepenny Review, P.O. Box 9131, Website address: www.threepennyreview.com Berkeley, California 94709 (telephone 510.849.4545). Unsolicited manuscripts must be accompanied by a stamped, self-addressed envelope. Consulting Editors: Editor and Publisher: Wendy Lesser Geoff Dyer Associate Editors: Sabrina Ramos Deborah Eisenberg Rose Whitmore Jonathan Franzen Louise Glück Art Advisors: Allie Haeusslein Janet Malcolm Sandra Phillips Ian McEwan Robert Pinsky Proofreader: Zachary Greenwald Kay Ryan Tobias Wolff Contents 3 Table Talk Jennifer Garfield 17 Poem: Asking for Light Louise Glück 5 Poem: Second Wind Mark Morris et al. 18 Symposium on Rhyme and Repetition Clifford Thompson 6 Memoir: The Home of Two Cliffs Wendy Lesser 22 Music: Back at the Berlin Philharmonic Madison Rahner 7 Poem: Sestina for the Matriarch Jim Powell 23 Poem: Inspecting the Game Brenda Wineapple 8 Books: The True History of the First Javier Marías 24 Perspective: Ridiculous Men Mrs.