Bradyarrhythmia in Mitral Valve Prolapse Treated with a Pacemaker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial

European Heart Journal (2004) Ã, 1–28 ESC Guidelines Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases Full Text The Task Force on the Diagnosis and Management of Pericardial Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology Task Force members, Bernhard Maisch, Chairperson* (Germany), Petar M. Seferovic (Serbia and Montenegro), Arsen D. Ristic (Serbia and Montenegro), Raimund Erbel (Germany), Reiner Rienmuller€ (Austria), Yehuda Adler (Israel), Witold Z. Tomkowski (Poland), Gaetano Thiene (Italy), Magdi H. Yacoub (UK) ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG), Silvia G. Priori (Chairperson) (Italy), Maria Angeles Alonso Garcia (Spain), Jean-Jacques Blanc (France), Andrzej Budaj (Poland), Martin Cowie (UK), Veronica Dean (France), Jaap Deckers (The Netherlands), Enrique Fernandez Burgos (Spain), John Lekakis (Greece), Bertil Lindahl (Sweden), Gianfranco Mazzotta (Italy), Joa~o Morais (Portugal), Ali Oto (Turkey), Otto A. Smiseth (Norway) Document Reviewers, Gianfranco Mazzotta, CPG Review Coordinator (Italy), Jean Acar (France), Eloisa Arbustini (Italy), Anton E. Becker (The Netherlands), Giacomo Chiaranda (Italy), Yonathan Hasin (Israel), Rolf Jenni (Switzerland), Werner Klein (Austria), Irene Lang (Austria), Thomas F. Luscher€ (Switzerland), Fausto J. Pinto (Portugal), Ralph Shabetai (USA), Maarten L. Simoons (The Netherlands), Jordi Soler Soler (Spain), David H. Spodick (USA) Table of contents Constrictive pericarditis . 9 Pericardial cysts . 13 Preamble . 2 Specific forms of pericarditis . 13 Introduction. 2 Viral pericarditis . 13 Aetiology and classification of pericardial disease. 2 Bacterial pericarditis . 14 Pericardial syndromes . ..................... 2 Tuberculous pericarditis . 14 Congenital defects of the pericardium . 2 Pericarditis in renal failure . 16 Acute pericarditis . 2 Autoreactive pericarditis and pericardial Chronic pericarditis . 6 involvement in systemic autoimmune Recurrent pericarditis . 6 diseases . 16 Pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade . -

Cardiac Involvement in COVID-19 Patients: a Contemporary Review

Review Cardiac Involvement in COVID-19 Patients: A Contemporary Review Domenico Maria Carretta 1, Aline Maria Silva 2, Donato D’Agostino 2, Skender Topi 3, Roberto Lovero 4, Ioannis Alexandros Charitos 5,*, Angelika Elzbieta Wegierska 6, Monica Montagnani 7,† and Luigi Santacroce 6,*,† 1 AOU Policlinico Consorziale di Bari-Ospedale Giovanni XXIII, Coronary Unit and Electrophysiology/Pacing Unit, Cardio-Thoracic Department, Policlinico University Hospital of Bari, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] 2 AOU Policlinico Consorziale di Bari-Ospedale Giovanni XXIII, Cardiac Surgery, Policlinico University Hospital of Bari, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] (A.M.S.); [email protected] (D.D.) 3 Department of Clinical Disciplines, School of Technical Medical Sciences, University of Elbasan “A. Xhuvani”, 3001 Elbasan, Albania; [email protected] 4 AOU Policlinico Consorziale di Bari-Ospedale Giovanni XXIII, Clinical Pathology Unit, Policlinico University Hospital of Bari, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] 5 Emergency/Urgent Department, National Poisoning Center, Riuniti University Hospital of Foggia, 71122 Foggia, Italy 6 Department of Interdisciplinary Medicine, Microbiology and Virology Unit, University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, Piazza G. Cesare, 11, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] 7 Department of Biomedical Sciences and Human Oncology—Section of Pharmacology, School of Medicine, University of Bari “Aldo Moro”, Policlinico University Hospital of Bari, p.zza G. Cesare 11, 70124 Bari, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (I.A.C.); [email protected] (L.S.) † These authors equally contributed as co-last authors. Citation: Carretta, D.M.; Silva, A.M.; D’Agostino, D.; Topi, S.; Lovero, R.; Charitos, I.A.; Wegierska, A.E.; Abstract: Background: The widely variable clinical manifestations of SARS-CoV2 disease (COVID-19) Montagnani, M.; Santacroce, L. -

J Wave Syndromes

Review Article http://dx.doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2016.46.5.601 Print ISSN 1738-5520 • On-line ISSN 1738-5555 Korean Circulation Journal J Wave Syndromes: History and Current Controversies Tong Liu, MD1, Jifeng Zheng, MD2, and Gan-Xin Yan, MD3,4 1Tianjin Key Laboratory of Ionic-Molecular Function of Cardiovascular disease, Department of Cardiology, Tianjin Institute of Cardiology, The Second Hospital of Tianjin Medical University, Tianjin, 2Department of cardiology, The Second Hospital of Jiaxing, Jiaxing, China, 3Lankenau Institute for Medical Research and Lankenau Medical Center, Wynnewood, Pennsylvania, USA, 4The First Affiliated Hospital, Medical School of Xi'an Jiaotong University, Xi'an, China The concept of J wave syndromes was first proposed in 2004 by Yan et al for a spectrum of electrocardiographic (ECG) manifestations of prominent J waves that are associated with a potential to predispose affected individuals to ventricular fibrillation (VF). Although the concept of J wave syndromes is widely used and accepted, there has been tremendous debate over the definition of J wave, its ionic and cellular basis and arrhythmogenic mechanism. In this review article, we attempted to discuss the history from which the concept of J wave syndromes (JWS) is evolved and current controversies in JWS. (Korean Circ J 2016;46(5):601-609) KEY WORDS: Brugada syndrome; Sudden cardiac death; Ventricular fibrillation. Introduction History of J wave and J wave syndromes The concept of J wave syndromes was first proposed in 2004 The J wave is a positive deflection seen at the end of the QRS by Yan et al.1) for a spectrum of electrocardiographic (ECG) complex; it may stand as a distinct “delta” wave following the QRS, manifestations of prominent J waves that are associated with a or be partially buried inside the QRS as QRS notching or slurring. -

The Syndrome of Alternating Bradycardia and Tachycardia by D

Br Heart J: first published as 10.1136/hrt.16.2.208 on 1 April 1954. Downloaded from THE SYNDROME OF ALTERNATING BRADYCARDIA AND TACHYCARDIA BY D. S. SHORT From the National Heart Hospita. Received September 15, 1953 Among the large number of patients suffering from syncopal attacks who attended the National Heart Hospital during a four-year period, there were four in whom examination revealed sinus bradycardia alternating with prolonged phases of auricular tachycardia. These patients presented a difficult problem in treatment. Each required at least one admission to hospital and in one case the symptoms were so intractable as to necessitate six admissions in five years. Two patients had mitral valve disease, one of them with left bundle branch block. One had aortic valve sclerosis while the fourth had no evidence of heart disease. THE HEART RATE The sinus rate usually lay between 30 and 50 a minute, a rate as slow as 22 a minute being observed in one patient (Table I). Sinus arrhythmia was noted in all four patients, wandering of TABLE I http://heart.bmj.com/ RATE IN SINus RHYTHM AND IN AURICULAR TACHYCARDIA Rate in Case Age Sex Associated Rate in auricular tachycardia heart disease sinus rhythm Auricular Venliicular 1 65 M Aortic valve sclerosis 28-48 220-250 60-120 2 47 F Mitral valve disease 35-75 180-130 90-180 on September 26, 2021 by guest. Protected copyright. 3 38 F Mitral valve disease 22-43 260 50-65 4 41 F None 35-45 270 110 the pacemaker in three, and periods of sinus standstill in two (Fig. -

Chest Pain and the Hyperventilation Syndrome - Some Aetiological Considerations

Postgrad Med J: first published as 10.1136/pgmj.61.721.957 on 1 November 1985. Downloaded from Postgraduate Medical Journal (1985) 61, 957-961 Mechanism of disease: Update Chest pain and the hyperventilation syndrome - some aetiological considerations Leisa J. Freeman and P.G.F. Nixon Cardiac Department, Charing Cross Hospital (Fulham), Fulham Palace Road, Hammersmith, London W6 8RF, UK. Chest pain is reported in 50-100% ofpatients with the coronary arteriograms. Hyperventilation and hyperventilation syndrome (Lewis, 1953; Yu et al., ischaemic heart disease clearly were not mutually 1959). The association was first recognized by Da exclusive. This is a vital point. It is time for clinicians to Costa (1871) '. .. the affected soldier, got out of accept that dynamic factors associated with hyperven- breath, could not keep up with his comrades, was tilation are commonplace in the clinical syndromes of annoyed by dizzyness and palpitation and with pain in angina pectoris and coronary insufficiency. The his chest ... chest pain was an almost constant production of chest pain in these cases may be better symptom . .. and often it was the first sign of the understood if the direct consequences ofhyperventila- disorder noticed by the patient'. The association of tion on circulatory and myocardial dynamics are hyperventilation and chest pain with extreme effort considered. and disorders of the heart and circulation was ackn- The mechanical work of hyperventilation increases owledged in the names subsequently ascribed to it, the cardiac output by a small amount (up to 1.3 1/min) such as vasomotor ataxia (Colbeck, 1903); soldier's irrespective of the effect of the blood carbon dioxide heart (Mackenzie, 1916 and effort syndrome (Lewis, level and can be accounted for by the increased oxygen copyright. -

Case Report: Cytarabine-Induced Pericarditis and Pericardial Effusion Rino Sato, MD and Robert Park, MD

HEMATOLOGY & ONCOLOGY Case Report: Cytarabine-Induced Pericarditis and Pericardial Effusion Rino Sato, MD and Robert Park, MD INTRODUCTION for inpatient chemotherapy, and demonstrated mild global left ventricular dysfunction with ejection fraction Cytarabine (cytosine arabinoside, Ara-C) is an antime- of 40%. The cardiomyopathy was attributed to his tabolite analogue of cytidine that is used as a chemo- underlying hypertension or sleep apnea, and not therapeutic agent for the treatment of acute myelogenous coronary artery disease based on a normal coronary leukemia and lymphocytic leukemias1 . The most computed tomography (CT) angiogram. The patient common side effects of this therapy include myelosup- was started on induction therapy with high-dose pression, pancytopenia, hepatotoxicity, gastrointestinal cytarabine therapy at 3g/m2 every twelve hours without ulceration with bleeding, and pulmonary infiltrates2. an anthracycline agent such as doxorubicin. Cardio-pulmonary complications of cytarabine therapy are uncommon, but include supraventricular and On day 5 of cytarabine therapy, the patient developed ventricular arrhythmias, sinus bradycardia, and recurrent non-radiating sharp chest pain that worsened with heart failure2, 3. Occasionally, patients may develop inspiration and palpation. He had no cough or sputum pericarditis leading to pericardial tamponade, which can production. His cardiac exam revealed a tri-phasic, be fatal. We report a case of cytarabine-induced high-pitched friction rub best heard over the left lower pericarditis and pericardial effusion to increase awareness sternal border. He was normotensive, did not have pulsus about this serious side effect of cytarabine and review paradoxus, and had minimally distended jugular veins. the current literature. An electrocardiogram revealed widespread concave ST-elevation and PR-depression in the limb leads (I, II, III, CASE PRESENTATION avF) and precordial leads (V5-V6) concerning for acute pericarditis (Figure 1). -

Case Report Chagas Cardiomyopathy Presenting As Symptomatic Bradycardia: an Underappreciated Emerging Public Health Problem in the United States

Hindawi Case Reports in Cardiology Volume 2017, Article ID 5728742, 5 pages https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/5728742 Case Report Chagas Cardiomyopathy Presenting as Symptomatic Bradycardia: An Underappreciated Emerging Public Health Problem in the United States Richard Jesse Durrance,1 Tofura Ullah,1 Zulekha Atif,1 William Frumkin,2 and Kaushik Doshi1 1 Department of Internal Medicine, Jamaica Hospital Medical Center, 8900 Van Wyck Expressway, Jamaica, NY 11418, USA 2Department of Cardiology, Jamaica Hospital Medical Center, 8900 Van Wyck Expressway, Jamaica, NY 11418, USA Correspondence should be addressed to Richard Jesse Durrance; [email protected] Received 13 February 2017; Accepted 18 July 2017; Published 16 August 2017 Academic Editor: Aiden Abidov Copyright © 2017 Richard Jesse Durrance et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Chagas cardiomyopathy (CCM) is traditionally considered a disease restricted to areas of endemicity. However, an estimated 300,000 people living in the United States today have CCM, of which its majority is undiagnosed. Wepresent a case of CCM acquired in an endemic area and detected in its early stage. A 42-year-old El Salvadoran woman presented with recurrent chest pain and syncopal episodes. Significant family history includes a sister inEl Salvador who also began suffering similar episodes. Physical exam and ancillary studies were only remarkable for sinus bradycardia. The patient was diagnosed with symptomatic sinus bradycardia and a pacemaker was placed. During her hospital course, Chagas serology was ordered given the epidemiological context from which she came. -

What Is an Arrhythmia?

ANSWERS Cardiovascular Conditions by heart What is an Arrhythmia? An arrhythmia is an abnormal heart rhythm. ECG strip showing a normal heartbeat It may feel like fluttering or a brief pause. It may be so brief that it doesn’t change your overall heart rate (the number of times per minute that your heart beats). Or it can cause the heart rate to be too slow or too fast. Some arrhythmias don’t cause any symptoms. Others ECG strip showing bradycardia can make you feel lightheaded or dizzy. There are two basic kinds of arrhythmias. Bradycardia is when the heart rate is too slow — less than 60 beats per minute. Tachycardia is when the heart rate is too fast — more than 100 beats per minute. ECG strip showing tachycardia What are the signs of arrhythmia? How are arrhythmias treated? • When it’s very brief, an arrhythmia can have almost Before treatment, it’s important for your doctor to no symptoms. It can feel like a skipped heartbeat know where an arrhythmia starts in the heart and that you barely notice. whether it’s abnormal. An electrocardiogram (ECG or • It also may feel like a fluttering in the chest or neck. EKG) is often used to diagnose arrhythmias. It creates a graphic record of the heart’s electrical impulses. • When arrhythmias are severe or last long enough to Using a Holter monitor, exercise stress tests, tilt table affect how well the heart works, the heart may not test and electrophysiologic studies (“mapping” the be able to pump enough blood to the body. -

Sinus Bradycardia

British Heart Journal, I97I, 33, 742-749. Br Heart J: first published as 10.1136/hrt.33.5.742 on 1 September 1971. Downloaded from Sinus bradycardia Dennis Eraut and David B. Shaw From the Cardiac Department, Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital, Exeter, Devon This paper presents thefeatures of 46 patients with unexplained bradycardia. Patients were ad- mitted to the study if their resting atrial rate was below 56 a minute on two consecutive occasions. Previous electrocardiograms and the response to exercise, atropine, and isoprenaline were studied. The ages of thepatients variedfrom I3 to 88years. Only 8 had a past history ofcardiovascular disease other than bradycardia, but 36 hJd syncopal or dizzy attacks. Of the 46 patients, 35 had another arrhythmia in addition to bradycardia; at some stage, i6 had sinus arrest, i.5 hadjunc- tional rhythm, 12 had fast atrial arrhythmia, I6 had frequent extrasystoles, and 6 had atrio- ventricular block. None had the classical features of sinoatrial block. Arrhythmias were often produced by exercise, atropine, or isoprenaline. Drug treatment was rarely satisfactory, but only i patient needed a permanent pacemaker. It is suggested that the majority of the patients were suffering from a pathological form of sinus bradycardia. The aetiology remains unproven, but the most likely explanation is a loss of the inherent rhythmicity of the sinoatrial node due to a primary degenerative disease. The descriptive title of 'the lazy sinus syndrome' is suggested. copyright. Bradycardia with a slow atrial rate is usually attempt to define the clinical syndrome of regarded as an innocent condition common in bradycardia with a pathologically slow atrial certain types of well-trained athlete, but occa- rate and to clarify the nature of the arrhyth- sionally it may occur in patients with symp- mia. -

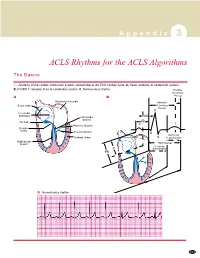

ACLS Rhythms for the ACLS Algorithms

A p p e n d i x 3 ACLS Rhythms for the ACLS Algorithms The Basics 1. Anatomy of the cardiac conduction system: relationship to the ECG cardiac cycle. A, Heart: anatomy of conduction system. B, P-QRS-T complex: lines to conduction system. C, Normal sinus rhythm. Relative Refractory A B Period Bachmann’s bundle Absolute Sinus node Refractory Period R Internodal pathways Left bundle AVN branch AV node PR T Posterior division P Bundle of His Anterior division Q Ventricular Purkinje fibers S Repolarization Right bundle branch QT Interval Ventricular P Depolarization PR C Normal sinus rhythm 253 A p p e n d i x 3 The Cardiac Arrest Rhythms 2. Ventricular Fibrillation/Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia Pathophysiology ■ Ventricles consist of areas of normal myocardium alternating with areas of ischemic, injured, or infarcted myocardium, leading to chaotic pattern of ventricular depolarization Defining Criteria per ECG ■ Rate/QRS complex: unable to determine; no recognizable P, QRS, or T waves ■ Rhythm: indeterminate; pattern of sharp up (peak) and down (trough) deflections ■ Amplitude: measured from peak-to-trough; often used subjectively to describe VF as fine (peak-to- trough 2 to <5 mm), medium-moderate (5 to <10 mm), coarse (10 to <15 mm), very coarse (>15 mm) Clinical Manifestations ■ Pulse disappears with onset of VF ■ Collapse, unconsciousness ■ Agonal breaths ➔ apnea in <5 min ■ Onset of reversible death Common Etiologies ■ Acute coronary syndromes leading to ischemic areas of myocardium ■ Stable-to-unstable VT, untreated ■ PVCs with -

The Causes of Heart Failure

The Causes of Heart Failure Andy Birchall HFSN A Birchall HF Sheffield Right Valve LVSD - heart regurgitation HFREF failure or stenosis Dropsy CCF – congestive Cor cardiac failure pulmonale Pulmonary hypertension HFPEF LVF A Birchall HF Sheffield Definitions Syndrome (collection of problems resulting in typical signs and symptoms) – lung crackles, raised JVP, fatigue, breathlessness, oedema (water retention) 3 main causes Diseased heart muscle High pressures (damaged structures, hypertension) Speed Many combinations Often more than one, often related A Birchall HF Sheffield The Heart is a pump designed for one way flow only Two ways in Two ways out • 4 chambers and 4 valves A Birchall HF Sheffield Normal function (left) The cardiac cycle – starting point at the mid relaxation (diastole) left side 1. when the pressure is high enough the mitral valve opens and the ventricle fill freely 2. the atria contract and fills the ventricle a further 25% 3 & 4. the ventricle contracts, mitral valve shuts, aortic valve opens and blood is sent up the aorta 5. aortic valve shuts as the ventricle relaxes and blood continues to return constantly to the heart and fills the atrium raising the pressure again A Birchall HF Sheffield Cardiac output explained Ejection fraction Volume squeezed out/full volume x 100% >60% = normal Cardiac output = vol ejected x pulse rate (ml/min) A Birchall HF Sheffield Types of heart failure 1. Due to a weak left ventricle 2. Due to aortic valve stenosis Left sided 3. Due to mitral valve regurgitation 4. Due to a stiff left ventricle 5. Due to pulmonary hypertension 6. -

Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Heart Diseasenormal AIRWAY

American Thoracic Society PATIENT EDUCATION | INFORMATION SERIES Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Heart DiseaseNORMAL AIRWAY Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a condition in NORMAL AIRWAY which you stop breathing during sleep because of a narrowed or closed breathing passage (airway). For people who have OSA and heart disease, heart problems can get worse if OSA is not recognized and treated. Untreated OSA can also put a dangerous OBSTRUCTED AIRWAY strain on your heart and blood vessels (cardiovascular OBSTRUCTED AIRWAY system). Common symptoms of obstructive sleep apnea include snoring, stopping breathing during sleep, frequent awakenings during the night and difficulty staying asleep throughout the night. It is also common for people who have obstructive in people who have atrial fibrillation treated with sleep apnea to be tired and sleepy during the day. catheter ablation (a special procedure done to This sleepiness can cause accidents at work, poor the heart), those with untreated obstructive sleep work performance, and car crashes. Obstructive apnea are 25% more likely to have their atrial sleep apnea can also have bad effects on your fibrillation return. heart and your blood vessels (arteries, veins and People with obstructive sleep apnea are also CLIP AND COPY AND CLIP capillaries). more likely to have coronary artery disease. What kinds of cardiovascular problems can I get Coronary artery disease (also known as the with obstructive sleep apnea? hardening of the arteries) happens when the Several cardiovascular conditions can happen with small blood vessels that supply blood and untreated obstructive sleep apnea. For example, oxygen to your heart become narrow. Narrowed if you have obstructive sleep apnea, you are more coronary arteries can lead to heart attacks and likely to have high blood pressure (hypertension) heart damage.