Berea College Fact Book 2005-2006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Industrial Resources: Bracken County - Augusta and Brooksville Kentucky Library Research Collections Western Kentucky University, [email protected]

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Bracken County Industrial Reports for Kentucky Counties 1976 Industrial Resources: Bracken County - Augusta and Brooksville Kentucky Library Research Collections Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/bracken_cty Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, Growth and Development Commons, and the Infrastructure Commons Recommended Citation Kentucky Library Research Collections, "Industrial Resources: Bracken County - Augusta and Brooksville" (1976). Bracken County. Paper 9. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/bracken_cty/9 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bracken County by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ' ^Ti AUGUSTA & BROOKSVILLE KENTUCKY ★ AUGUSTA ^So SCO miles BRACKEN COUNTY, KENTUCKY BROOKSVILLE, KENTUCKY — Site No. 176 -- 38 Acres For more information contact Mr. William Wallin, Post Office Box 5, Brooksville, Kentucky 41004, or the Kentucky Department of Commerce, Capital Plaza Tower, Frankfort, Kentucky 40601. LOCATION: Adjacent to eastern city limits ZONING: None HIGHWAY ACCESS: KY 10 adjacent to southern boundary i RAl LROAD: Not rail served WATER: Brooksville Utility System Size Line: 8-inch line along western boundary GAS: Natural gas service not available ELECTRICITY: Kentucky Utilities Company SEWERAGE: Brooksville Utility System Size Line: 8-inch line across KY 10 from southern boundary of site OWNERSHIP: Private SCALE; 1 inch = 1200 feet UTILITIES CONTOUR INTERVAL: 20 feet ■■■■• Water Line BASE: USGS 7.5 minute series - 1952 • Sewer Line INDUSTRIAL RESOURCES AUGUSTA AND BROOKSVILLE, KENTUCKY Prepared by The Kentucky Department of Commerce in cooperation with The Cities of Augusta and Brooksville 1976 This copy has been prepared by the Kentucky Department of Commerce, Division of Research and Planning, and the cost of printing paid from state funds. -

2011 AIKCU Technology Awards

2011 AIKCU Technology Awards ASSOCIATION OF INDEP E N D E N T KENTUCKY COLLEGES AN D BEST NEW CAMPUS BEST STUDENT ONLINE SERVICE APPLICATIONUNIVERSITIES SYSTEM Nominees are: Nominees are: Campbellsville University - CASHNet Portal Integration Berea College - New Student Online Orientation and Transylvania University - MOX Mobil Application Course Registration System Georgetown College - GC Mobile University of the Cumberlands - Roommate Student Housing System Transylvania University - Campus Digital Signage Union College - PWM Open Source Password Self University of the Cumberlands - UC Website Service for LDAP Directories This award is given to the school who has demonstrated the University of the Cumberlands - EDUCAN spirit of digital use by providing the most efficient, effective, University of the Cumberlands - Efficient Asset and creative online services to their students. Management System University of the Cumberlands - Time and MOST SUCCESSFUL Attendance INFRASTRUCTURE PROJECT University of Pikeville - Retension Alert This award is given to the school that has implemented a Nominees are: major new application or has significantly enhanced an existing system that improves operational performance and/or service Brescia University - Securing Campus Network for all or part of its students, faculty, and staff. Access for Improved User Experience Campbellsville University - Virtualization Initiative MOST INNOVATIVE USE OF Centre College - Watchtower TECHNOLOGY FOR INSTRUCTIONAL PURPOSES Transylvania University – PaperCut Print Control University of the Cumberlands - UC Wireless Nominees are: University of the Cumberlands - Network Berea College - BC-OnDemand Infrastructure Expansion Project University of the Cumberlands - iLearn Bypass This award is given to the school that has implemented Exams major changes to its technology infrastructure resulting in improved services and/or cost savings. -

Patriots, Pioneers and Presidents Trail to Discover His Family to America in 1819, Settling in Cincinnati

25 PLACES TO VISIT TO PLACES 25 MAP TRAIL POCKET including James Logan plaque, High Street, Lurgan FROM ULSTER ULSTER-SCOTS AND THE DECLARATION THE WAR OF 1 TO AMERICA 2 COLONIAL AMERICA 3 OF INDEPENDENCE 4 INDEPENDENCE ULSTER-SCOTS, The Ulster-Scots have always been a transatlantic people. Our first attempted Ulster-Scots played key roles in the settlement, The Ulster-Scots/Scotch-Irish contribution to the Patriot cause in the events The Ulster-Scots/Scotch-Irish played important roles in the military aspects of emigration was in 1636 when Eagle Wing sailed from Groomsport for New England administration and defence of Colonial America. leading up to and including the American War of Independence was immense. the War of Independence. General Richard Montgomery was the descendant of SCOTCH-IRISH but was forced back by bad weather. It was 1718 when over 100 families from the Probably born in County Donegal, Rev. Charles Cummings (1732–1812), a a Scottish cleric who moved to County Donegal in the 1600s. At a later stage the AND SCOTS-IRISH Bann and Foyle river valleys successfully reached New England in what can be James Logan (1674-1751) of Lurgan, County Armagh, worked closely with the Penn family in the Presbyterian minister in south-western Virginia, is believed to have drafted the family acquired an estate at Convoy in this county. Montgomery fought for the regarded as the first organised migration to bring families to the New World. development of Pennsylvania, encouraging many Ulster families, whom he believed well suited to frontier Fincastle Resolutions of January 1775, which have been described as the first Revolutionaries and was killed at the Battle of Quebec in 1775. -

Master of Science State & Institutional

Master of Science State & Institutional Representation 2012 - 2020 Alma Maters Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College Drury University Alice Lloyd College East Tennessee State University Allegheny College Eastern Kentucky University Appalachian State University Elon University Arizona State University Emory University Auburn University Emory & Henry College Augustana College Ferris State University Austin Peay State University Ferrum College Bakersfield College Florida A&M University Ball State University Florida Atlantic University Barry University Florida Gulf Coast University Baylor University Florida Institute of Technology Belmont University Florida International University Benedictine University Florida Southern University Bellevue University Florida State University Belmont University Franciscan University of Steubenville Berea College George Mason University Berry College Georgetown College Bowling Green State University Georgetown University Brigham Young University George Washington University Brown University Georgia Gwinnett College California Lutheran University Georgia Institute of Technology California State Polytechnic University-Pomona Gonzaga University California State University Grand Valley State University California State University Bernardino Hanover College California State University Fullerton Houghton College California State University Long Beach Houston Baptist University California State University Los Angeles Howard University Campbellsville University Hunter College Carson-Newman University Illinois Wesleyan -

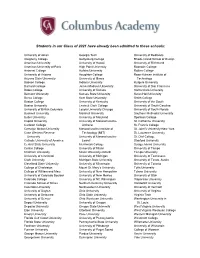

Students in Our Class of 2021 Have Already Been Admitted to These Schools

Students in our Class of 2021 have already been admitted to these schools: University of Akron Georgia Tech University of Redlands Allegheny College Gettysburg College Rhode Island School of Design American University University of Hawaii University of Richmond American University of Paris High Point University Roanoke College Amherst College Hofstra University Rollins College University of Arizona Houghton College Rose-Hulman Institute of Arizona State University University of Illinois Technology Babson College Indiana University Rutgers University Barnard College James Madison University University of San Francisco Bates College University of Kansas Santa Clara University Belmont University Kansas State University Seton Hall University Berea College Kent State University Smith College Boston College University of Kentucky University of the South Boston University Lewis & Clark College University of South Carolina University of British Columbia Loyola University Chicago University of South Florida Bucknell University Marshall University Southern Methodist University Butler University University of Maryland Spelman College Capital University University of Massachusetts- St. Catherine University Carleton College Amherst St. Francis College Carnegie Mellon University Massachusetts Institute of St. John’s University-New York Case Western Reserve Technology (MIT) St. Lawrence University University University of Massachusetts- St. Olaf College Catholic University of America Lowell Stanford University Central State University Merrimack College -

FICE Code List for Colleges and Universities (X0011)

FICE Code List For Colleges And Universities ALABAMA ALASKA 001002 ALABAMA A & M 001061 ALASKA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY 001005 ALABAMA STATE UNIVERSITY 066659 PRINCE WILLIAM SOUND C.C. 001008 ATHENS STATE UNIVERSITY 011462 U OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE 008310 AUBURN U-MONTGOMERY 001063 U OF ALASKA FAIRBANKS 001009 AUBURN UNIVERSITY MAIN 001065 UNIV OF ALASKA SOUTHEAST 005733 BEVILL STATE C.C. 001012 BIRMINGHAM SOUTHERN COLL ARIZONA 001030 BISHOP STATE COMM COLLEGE 001081 ARIZONA STATE UNIV MAIN 001013 CALHOUN COMMUNITY COLLEGE 066935 ARIZONA STATE UNIV WEST 001007 CENTRAL ALABAMA COMM COLL 001071 ARIZONA WESTERN COLLEGE 002602 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 001072 COCHISE COLLEGE 012182 CHATTAHOOCHEE VALLEY 031004 COCONINO COUNTY COMM COLL 012308 COMM COLLEGE OF THE A.F. 008322 DEVRY UNIVERSITY 001015 ENTERPRISE STATE JR COLL 008246 DINE COLLEGE 001003 FAULKNER UNIVERSITY 008303 GATEWAY COMMUNITY COLLEGE 005699 G.WALLACE ST CC-SELMA 001076 GLENDALE COMMUNITY COLL 001017 GADSDEN STATE COMM COLL 001074 GRAND CANYON UNIVERSITY 001019 HUNTINGDON COLLEGE 001077 MESA COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001020 JACKSONVILLE STATE UNIV 011864 MOHAVE COMMUNITY COLLEGE 001021 JEFFERSON DAVIS COMM COLL 001082 NORTHERN ARIZONA UNIV 001022 JEFFERSON STATE COMM COLL 011862 NORTHLAND PIONEER COLLEGE 001023 JUDSON COLLEGE 026236 PARADISE VALLEY COMM COLL 001059 LAWSON STATE COMM COLLEGE 001078 PHOENIX COLLEGE 001026 MARION MILITARY INSTITUTE 007266 PIMA COUNTY COMMUNITY COL 001028 MILES COLLEGE 020653 PRESCOTT COLLEGE 001031 NORTHEAST ALABAMA COMM CO 021775 RIO SALADO COMMUNITY COLL 005697 NORTHWEST -

Berea College: an Illustrated History

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Higher Education Education 3-3-2006 Berea College: An Illustrated History Shannon H. Wilson Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Wilson, Shannon H., "Berea College: An Illustrated History" (2006). Higher Education. 15. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_higher_education/15 Wilson FM•i-xii 11/21/05 7:54 PM Page i Berea College Wilson FM•i-xii 11/21/05 7:54 PM Page ii Wilson FM•i-xii 11/21/05 7:54 PM Page iii BEREA COLLEGE an illustrated history Shannon H. Wilson The University Press of Kentucky Wilson FM•i-xii 11/21/05 7:54 PM Page iv Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 2006 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508–4008 www.kentuckypress.com 10 09 08 07 06 5 4 3 2 1 All photographs, unless otherwise noted, are from the Berea College Archives. -

Fee, John Gregg, House 08/26/1980

Form No. 10-300 REV. (9/77) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FOR NPS USE ONLY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE RECEIVED JUN 2 5 1980 NATIONAL REGISTER OF fflSTORIC PLACES AUG 2 6 (980 INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM DATiENTERED SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS Qname HISTORIC 1 John Gregg': Fee iHouse AND/OR tOMMON 0LOCATION t'J ^ STREETS. NUMBER ) —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN . 1 CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT ■Chatham i,)-- 0 2L VICINITY OF 07 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Kentucky 021 Bracken 023 Hclassification CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT —PUBLIC X.OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM J£BUILDING(S) ^.PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL ^PRIVATE RESIDENCE SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE ENTERTAINMENT RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS JCYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OfOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Mr. James T. Norris STREETS. NUMBER Box 213 CITY, TOWN STATE VICINITYOF Kentucky 41101 [LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC. Bracken Comty Courthouse STREETS. NUMBER Main Street CITY, TOWN STATE Brooksville Kentucky a REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS title Survey of Historic Sites in Kentucky DATE 1979 —FEDERAL .XSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Kentucky Heritage Commission CITY, TOWN STATE Frankfort Kentucky DESCRIPTION .i' CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED iORIGINALSITE ^GOOD —RUINS ^ALTERED —MOVED DATE- —FAIR —UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Bracken County, Kentucky, located on the Ohio River in the northeastern part of the state, is largely a rural area comprised of small towns and villages. -

Transforming Poverty Studies in the United States

Transforming Poverty Studies in the United States OUR MISSION The Shepherd Higher Education Consortium on Poverty (SHECP) encourages the study of poverty as a complex social problem, by expanding and improving educational opportunities for college students in a wide range of disciplines and career trajectories. Through its programs, SHECP and its member institutions prepare students for a lifetime of professional and civic efforts to diminish poverty and enhance human capability, while also supporting connections among students, faculty, staff, and alumni engaged in the study of poverty. SHECP is a collaboration In 2019, SHECP provided SHECP interns contributed among 25 colleges and 121 students with summer 33,880 hours of service in universities that integrates internships, in 18 geographic 2019. A force multiplier, they classroom study of poverty locations, with 84 poverty- built capacity for our partners with summer internships and focused nonprofit and while delivering $862K in co-curricular activities. government agencies. community impact. “A knowledgeable THE NEED and sympathetic graduate pool An estimated 38.1 million Americans live in poverty (11.8 percent of the population), according to a 2019 report issued may be the most by the United States Census Bureau. important advance Higher education in the U.S. is not meeting the demand from to diminish U.S. students aspiring to consider the moral and social problems associated with poverty. SHECP fills that gapby offering poverty since the a sustained education to understand the complexities of War on Poverty.” poverty. Through classroom study and experiential learning — David Bradley opportunities, these future professionals learn how their Executive Director work and civic activity will inevitably impinge on poverty. -

Black Evangelicals and the Gospel of Freedom, 1790-1890

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2009 SPIRITED AWAY: BLACK EVANGELICALS AND THE GOSPEL OF FREEDOM, 1790-1890 Alicestyne Turley University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Turley, Alicestyne, "SPIRITED AWAY: BLACK EVANGELICALS AND THE GOSPEL OF FREEDOM, 1790-1890" (2009). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 79. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/79 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Alicestyne Turley The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2009 SPIRITED AWAY: BLACK EVANGELICALS AND THE GOSPEL OF FREEDOM, 1790-1890 _______________________________ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION _______________________________ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Alicestyne Turley Lexington, Kentucky Co-Director: Dr. Ron Eller, Professor of History Co-Director, Dr. Joanne Pope Melish, Professor of History Lexington, Kentucky 2009 Copyright © Alicestyne Turley 2009 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION SPIRITED AWAY: BLACK EVANGELICALS AND THE GOSPEL OF FREEDOM, 1790-1890 The true nineteenth-century story of the Underground Railroad begins in the South and is spread North by free blacks, escaping southern slaves, and displaced, white, anti-slavery Protestant evangelicals. This study examines the role of free blacks, escaping slaves, and white Protestant evangelicals influenced by tenants of Kentucky’s Second Great Awakening who were inspired, directly or indirectly, to aid in African American community building. -

Past Presidents and Conference Chairs

Past Presidents and Conference Chairs 2019 – Barb Milosch, Sayre School, President Kara Salsman, Transylvania University, Pres-elect/Conference Chair 2018 – Laurel Raimondo Martin, Bluegrass Community & Technical College, President Barb Milosch, Sayre School, Pres-elect/Conference Chair 2017 – Laurel Raimondo Martin, Bluegrass Community & Technical College, President/Conference Chair Jey Marks, Northern Kentucky, Pres-elect/Conference Chair (Resigned) 2016 – Diana McKenzie, Transylvania University, President Laurel Raimondo Martin, Bluegrass Community & Technical College, Pres-elect/Conference Chair 2015 – Jill Smith, University of Kentucky, President Diana McKenzie, Transylvania University, Pres-elect/Conference Chair 2014 – Monica Ginney, Thomas More College, President Jill Smith, University of Kentucky, Pres-elect/Conference Chair 2013 – Mary Beth Neiser, University of Kentucky, President Monica Ginney, Thomas More College, Pres-elect/Conference Chair 2012 – Dwight Dozier, University of Louisville, President Mary Beth Neiser, University of Kentucky, Pres-elect/Conference Chair 2011 – Natasa Mongiardo, Transylvania University, President Dwight Dozier, University of Louisville, Pres-elect/Conference Chair 2010 – Phillip James, Morehead State University, President Natasa Mongiardo, Transylvania University, Pres-elect/Conference Chair 2009 – Ron Wilson, Western Kentucky University, President Phillip James, Morehead State University, Pres-elect/Conference Chair 2008 – Mimi Ward, University of Kentucky, President Ron Wilson, Western Kentucky -

The Oberlin Group Scientific American Letter 10092009-1

October 15, 2009 Steven Inchcoombe, Managing Director, Nature Publishing Group The Macmillan Building 4 Crinan Street, London N1 9XW United Kingdom Dear Mr. Inchcoombe: We the undersigned are all library directors of liberal arts college libraries and members of the Oberlin Group, a consortium of eighty selective liberal arts college libraries in the United States. As such we are concerned with the education of tens of thousands of undergraduate students each year. A twenty‐first century liberal arts education includes an understanding of the scientific and technological underpinnings of our society. We seek to provide the students and faculty of our institutions with access to a broad range of scientific literature, including accessible, popular scientific journalism. As such, your increase in the 2010 subscription price for Scientific American magazine from $39.95 to $299 in print and from $1,000 to $1500 (depending on the size of the college) for an annual license for the online version of the magazine is unreasonable and hinders our ability to meet the information needs of our library users. This increase is disturbing for a number of reasons. First, the announcement of the increase came as many libraries were in the final stages of renewing their annual subscriptions to journals, magazines, and newspapers. This gives us little time to consult with our library users and make a considered decision about whether to cancel this subscription or not. Secondly, this increase comes during a severe economic recession, when most libraries are cutting costs and are asking publishers and other vendors to preserve long standing relationships by holding down or forgoing price increases.