Somalia – President Mohamud on the Back Foot While Al-Shabaab Attacks Continue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USIP's Work in Somalia

USIP’s Work in Somalia Making Peace Possible UNMISS Photo/JC Mcilwaine CURRENT SITUATION After decades of civil war and the collapse of the central government in 1991, Somalis and international supporters have made progress in re-establishing state structures, such as a provisional 2012 constitution and the country’s first elections for a government since 1969. The African Union and the United Nations, with U.S. assistance, support the Federal Government of Somalia in restoring President Hassan Sheikh institutions. Still, continued attacks by the al-Shabab Mohamud on His Plan for extremist group, plus corruption and regional and clan Peace disputes, have complicated the government’s efforts to Somalia’s president spoke hold popular elections and establish stable governance. For example, consensus still must be at USIP in April 2016 to lay reached about the composition, boundaries, and powers of Somalia’s constituent states. The out his government’s plan government was unable to hold a direct vote for president in 2016 and scheduled an indirect for stabilizing his country— election in parliament for February 2017. Of an estimated 10 million Somalis, more than 2 million and Somalia’s need for are displaced and 5 million need humanitarian assistance, according to U.N. agencies. international support in that USIP’S WORK effort. The U.S. Institute of Peace (USIP) provides education, grants, training, and resources to help Somalis strengthen the institutions and skills needed to build a more stable, resilient society and state. USIP works through partnerships with Somali civil society organizations and government institutions, the U.S. State Department, non-governmental organizations, and the large Somali diaspora around the globe. -

United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia (UNSOM) SRSG Kay

United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia (UNSOM) For Immediate Release PRESS STATEMENT 51/2014 SRSG Kay meets with Somali officials and foreign diplomats, calling for political stability ahead of Copenhagen Conference Mogadishu, 16 November 2014 – United Nations Special Representative of the Secretary- General (SRSG) Nicholas Kay met with Somali political leaders on 16 November 2014. He was joined by Danish Ambassador Geert Aagaard Andersen, European Union (EU) Special Representative for the Horn of Africa Alex Rondos, EU Special Envoy to Somalia Michele Cervone d'Urso, Italian Ambassador Fabrizio Marcelli, Swedish Ambassador Mikael Lindvall and UK Ambassador Neil Wigan for meetings with His Excellency President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, His Excellency Prime Minister Abdiweli Sheikh Ahmed and His Excellency Speaker of the Federal Parliament Mohamed Osman Jawari. They discussed the ongoing political crisis and urged the leaders to find a solution that would allow the Federal Government to implement the Vision 2016 plan for Somalia’s political transformation in a timely manner. Their meetings came as the Federal Government and Somalia’s international partners prepare for the first Ministerial-level High Level Partnership Forum (HLPF) in Copenhagen on 19 and 20 November. “The HLPF will be a critical opportunity to review progress and chart the way ahead for the implementation of the New Deal Somali Compact. The Compact brings together national priorities agreed amongst the Somali people, the Federal Government and the international community. Much has been achieved, particularly through the concerted and joint efforts of the Federal Government. But significant challenges remain. The ongoing political crisis in Somalia is a serious risk to further progress. -

SRSG Kay Encouraged by Firm Commitment to Somalia's Vision

UNITED NATIONS ASSISTANCE MISSION IN SOMALIA (UNSOM) PRESS RELEASE 10/2015 SRSG Kay encouraged by firm commitment to Somalia’s Vision 2016 timetable Mogadishu, 18 March 2015 – The Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General for Somalia (SRSG) Nicholas Kay, welcomed firm commitments made by Somalia’s Federal and regional leaders to meet key Vision 2016 deadlines to complete Somalia’s federal state formation process, and review the provisional constitution without any extension of the terms of the Federal President and Parliament in September 2016, as set out in the provisional federal Constitution. During the last ten days SRSG Kay has met with Somalia’s President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, Prime Minister Omar Abdirashid Ali Sharmarke and the Speaker of the Federal Parliament, Mohamed Osman Jawari, to discuss peace and state-building progress across the country. He also travelled to Garowe, Kismayo and Baidoa and met with the leaders of Puntland, Abdiweli Mohamed Ali Gaas, the Interim Juba Administration (IJA), Sheikh Ahmad Islam ‘Madobe’, and the Interim South West Administration (ISWA) Sheikh Sharif Hassan Adan. Recalling his mandate from the Security Council to provide the good offices of the United Nations and strategic policy advice to assist Somalia’s peace-building and state- building efforts, SRSG Kay noted, “I am encouraged by the firm commitments I have heard from the President, Prime Minister, Speaker and the leaders of Puntland, the IJA and the ISWA to delivering Somalia’s Vision 2016 plan without any extension of the term -

Annual Report 2014

Heritage Institute for Policy Studies Annual Report 20141 Table of Contents Message from the Director........................................................ 3-4 Programs ................................................................................. 5-9 Research and Analysis. ............................................................ 10 Impact ..................................................................................... 11 Feedback ................................................................................. 12 Lessons Learned ...................................................................... 12 Partnerships ............................................................................. 13 Financial Highlights ................................................................ 14-15 Security, Justice and Rights ..................................................... 16 Aid and Development ............................................................. 17 About HIPS ............................................................................. 18 Statutes ................................................................................... 19 Appendices ............................................................................. 20 Staff & Fellows .......................................................... 20 Board of Advisors ..................................................... 21 Message from the Executive Director Thanks to the collective efforts of our dedicated team, 2014 was an exciting year for the Heritage Institute for -

Security Council Provisional Asdfsixty-Eighth Year 6975Th Meeting Thursday, 6 June 2013, 10 A.M

United Nations S/PV.6975 Security Council Provisional asdfSixty-eighth year 6975th meeting Thursday, 6 June 2013, 10 a.m. New York President: Mr. Simmonds ................................... (United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland) Members: Argentina ....................................... Ms. Millicay Australia . Mr. Quinlan Azerbaijan ...................................... Mr. Mehdiyev China .......................................... Mr. Li Baodong France .......................................... Mr. Bertoux Guatemala ....................................... Mr. Briz Gutiérrez Luxembourg ..................................... Ms. Lucas Morocco ........................................ Mr. Bouchaara Pakistan ........................................ Mr. Masood Khan Republic of Korea ................................. Mr. Sul Kyung-hoon Russian Federation ................................ Mr. Pankin Rwanda ......................................... Mr. Gasana Togo ........................................... Mr. Menan United States of America ........................... Mr. DeLaurentis Agenda The situation in Somalia Report of the Secretary-General on Somalia (S/2013/326) This record contains the text of speeches delivered in English and of the interpretation of speeches delivered in the other languages. The final text will be printed in the Official Records of the Security Council. Corrections should be submitted to the original languages only. They should be incorporated in a copy of the record and sent under the signature of -

A Week in the Horn 18.9.2015 News in Brief the TPDM Leader And

A Week in the Horn 18.9.2015 News in brief The TPDM leader and hundreds of fighters return to Ethiopia Steadily expanding Ethiopia-China bilateral ties September 18 - a bleak and dismal anniversary for Eritrea Inauguration of President Ahmed “Madobe” concludes the Jubaland State process European Union to help Africa address the migration and refugee crisis Israel and Ethiopia: the annual trade fair in Addis Ababa News in Brief Africa and the African Union The Chairperson of the Commission of the African Union, Dr. Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma, on Thursday (September 17) reiterated the AU‘s strong condemnation of the unjustifiable abduction and the continued detention of the leaders of the Transition in Burkina Faso. It was ―an act of terrorism in all respects‖. Dr. Dlamini-Zuma welcomed the unanimous condemnation by the international community of these acts, which, she said, constituted a serious threat to peace, stability and security in Burkina Faso, the region and the rest of Africa. IGAD launched preparations for an IGAD Regional Climate Change Strategy for the next five years (2016-2020) at a Consultative Meeting held at the IGAD Secretariat in Djibouti on Monday (September 14). The IGAD Climate Prediction and Application Center (ICPAC) is taking the lead in preparation of the IRCCS which is expected to be finalized in January 2016. Ethiopia President Dr. Mulatu Teshome on Friday (September 11) urged all Ethiopians to exert more efforts in order to make a success of the Second Growth and Transformation Plan and achieve its aims. He said the success of the Government‘s foreign policy had helped Ethiopia become an island of peace and stability in the Horn of Africa. -

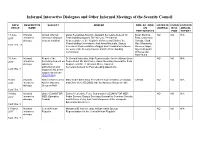

Informal Interactive Dialogues and Other Informal Meetings of the Security Council

Informal Interactive Dialogues and Other Informal Meetings of the Security Council DATE/ DESCRIPTIVE SUBJECT BRIEFER NON- SC / NON- LISTED IN LISTED LISTED IN VENUE NAME UN JOURNAL IN SC ANNUAL PARTICIPANTS POW REPORT 19 June Informal Annual informal Oscar Fernández-Taranco, Assistant Secretary-General for Brazil, Burkina NO NO N/A 2017 interactive interactive dialogue Peacebuilding Support; Tae-Yul Cho, Permanent Faso, Cameroon, dialogue on peacebuilding Representative of the Republic of Korea and Chair of the Canada, Chad, Peacebuilding Commission; Ihab Awad Moustafa, Deputy Mali, Mauritania, Conf. Rm. 12 Permanent Representative of Egypt and Coordinator between Morocco, Niger, the work of the Security Council and the Peacebuilding Nigeria Republic Commission of Korea and Switzerland 15 June Informal Report of the Dr. Donald Kaberuka, High Representative for the African Union NO NO N/A 2017 interactive Secretary-General on Peace Fund, Mr. Atul Khare, Under-Secretary-General for Field dialogue options for Support, and Mr. El-Ghassim Wane, Assistant authorization and Secretary-General for Peacekeeping Operations Conf. Rm. 7 support to AU peace support operations (S/2017/454) 9 June Informal Haiti / Activities of the Marc-André Blanchard, Permanent Representative of Canada Canada NO NO N/A 2017 interactive Ad Hoc Advisory and Chair of the ECOSOC Ad Hoc Advisory Group on Haiti dialogue Group on Haiti Conf. Rm. 7 31 May Informal Libya / EUNAVFOR Enrico Credentino, Force Commander of EUNAVFOR MED; NO NO N/A 2017 interactive MED (Operation Pedro Serrano, Deputy Secretary General for Common Security dialogue Sophia) and Defence Policy and Crisis Response at the European External Action Service Conf. -

United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia Unsom

UNITED NATIONS NATIONS UNIES UNITED NATIONS ASSISTANCE MISSION IN SOMALIA UNSOM SRSG Nicholas Kay’s speech on the signing of the agreement on Interim Jubba Administration Addis Ababa, 28 August 2013 Your Excellency, Dr. Tedros Adhanom, Foreign Minister of Ethiopia and Chair of the Council of Ministers of IGAD and dear colleagues Let me begin by giving a very very sincere welcome to the agreement and join my voice to the very well deserved praise for the role of IGAD and the Ethiopian chairmanship of H.E. Dr. Tedros and I can bear witness to the unstinting tireless hours that he has put in. Not least you can follow him also on Twitter and you can find that by the time he tweets there is perfect evidence that he is up at odd hours during these negotiations. 3am was his last tweet! And well deserved congratulations to the IGAD Executive Secretary, H.E. Ambassador Engineer Mahboub Maalim and as well as it has been mentioned General Gebre, IGAD Facilitator. Everybody deserves praise but particularly I salute President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud’s statesmanship and leadership and Sheikh Mohamed Ahmed Islaan or Sheikh Madobe’s courage and commitment to the political process. This agreement is a breakthrough. It helps resolve a political impasse which had been holding up progress and unlocks the door to a better future for Somalia. But I think it is important to stress that everyone is a winner. Both parties manifested remarkable patience, persistence, wisdom and political commitment. They all acted in the greater interest of the country and moving towards a more stable future. -

Security Council Distr.: General 3 March 2014

United Nations S/2014/140 Security Council Distr.: General 3 March 2014 Original: English Report of the Secretary-General on Somalia I. Introduction 1. The present report is submitted pursuant to paragraph 13 of Security Council resolution 2102 (2013), in which the Council requested me to keep it regularly informed of the implementation of the mandate of the United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia (UNSOM) and to provide an assessment of the political and security implications of wider United Nations deployments across Somalia every 90 days. The present report covers major developments that occurred during the period from 16 November 2013 to 15 February 2014. II. Political and security developments A. Political situation 2. The political landscape in Somalia was dominated by the formation of a new cabinet, with regional political processes showing promising signs. Indirect elections in Puntland State of Somalia led to the selection of a new President. In addition, the inauguration of the Interim Juba Administration, witnessed by the international community, and the holding of talks between the Federal Government of Somalia and “Somaliland” were positive steps forward. 3. On 2 December 2013, Prime Minister Abdi Farah Shirdon lost a no confidence motion in the Somali Federal Parliament. On 12 December, following extensive consultations, President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud nominated Abdiweli Sheikh Ahmed as the new Prime Minister. He was endorsed by the Parliament on 21 December, and on 17 January, Mr. Ahmed announced the formation of his expanded cabinet composed of 25 members, including 2 women. 4. Elsewhere, on 8 January, the Parliament of Puntland elected Abdiweli Mohamed Ali Gaas President for a five-year term. -

1411762* A/Hrc/25/Ngo/158

United Nations A/HRC/25/NGO/158 General Assembly Distr.: General 5 March 2014 English only Human Rights Council Twenty-fifth session Agenda item 3 Promotion and protection of all human rights, civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights, including the right to development Written statement* submitted by the Society for Threatened Peoples, a non-governmental organization in special consultative status The Secretary-General has received the following written statement which is circulated in accordance with Economic and Social Council resolution 1996/31. [18 February 2014] * This written statement is issued, unedited, in the language(s) received from the submitting non-governmental organization(s). GE.14-11762 *1411762* A/HRC/25/NGO/158 Situation in Somalia Somalia is a Federal State. Federalism corresponds with the diversity of the Somali society. Somalia often has been presented as a homogenous nation of Somali people who share one language, one religion and one culture, as a nation without minorities. Although there is a predominance of four Somali majority clans (Darod, Hawiye, Dir, Rahanweyn) which have been controlling government, politics and the economy for decades, according to estimations one third of the total Somalia population of 9.5 million people are belonging to minority groups (Yibir, Gaboye, Eyle,Galgala, Tumal and other groups). Somalia’s minorities are diverse and not framed simply by different ethnic or linguistic backgrounds, but also by diverging social situations. Although the Provisional Constitution of Somalia of August 2012 rejects secession, it promotes voluntary federalism of regions while establishing a decentralized democratic unitary government. But this system of clan federalism is flawed because persistent rivalries between the most powerful clans which deny equal rights and representation to smaller clans and minorities. -

Supporting a Federal Future for Somalia: the Role of UNSOM

Africa Programme Summary Supporting a Federal Future for Somalia: The Role of UNSOM Speaker: Ambassador Nicholas Kay Special Representative of the UN Secretary General for Somalia; Head, United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia (UNSOM) Chair: Mohamed A Omaar Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister of Somalia (2010–11) 13 June 2014 The views expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the speaker(s) and participants do not necessarily reflect the view of Chatham House, its staff, associates or Council. Chatham House is independent and owes no allegiance to any government or to any political body. It does not take institutional positions on policy issues. This document is issued on the understanding that if any extract is used, the author(s)/ speaker(s) and Chatham House should be credited, preferably with the date of the publication or details of the event. Where this document refers to or reports statements made by speakers at an event every effort has been made to provide a fair representation of their views and opinions. The published text of speeches and presentations may differ from delivery. 10 St James’s Square, London SW1Y 4LE T +44 (0)20 7957 5700 F +44 (0)20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org Patron: Her Majesty The Queen Chairman: Stuart Popham QC Director: Dr Robin Niblett Charity Registration Number: 208223 2 Supporting a Federal Future for Somalia: The Role of UNSOM Introduction This document provides a summary of a meeting and questions-and-answers session held at Chatham House on 9 May 2014 that focused on the role of United Nations Assistance Mission in Somalia (UNSOM) in a future federal Somalia. -

Export Agreement Coding (PDF)

Peace Agreement Access Tool PA-X www.peaceagreements.org Country/entity Somalia Region Africa (excl MENA) Agreement name Central Regions State Formation Agreement (Mudug and Galgadug) Date 30/07/2014 Agreement status Multiparty signed/agreed Interim arrangement No Agreement/conflict level Intrastate/local conflict ( Somali Civil War (1991 - ) ) Stage Framework/substantive - partial (Core issue) Conflict nature Government/territory Peace process 87: Somalia Peace Process Parties Galmudug State, Abdi Hassan Awale Qeybdid; Ahlu Sunna wal Jamaa Administration, Sheikh Ibrahim Sheikh Gureye; Himan and Heeb Administration, Abdullahi Mohamed Ali (Barleh); FGS, Mustafa Shiekh Ali Dhuhulow, Duale Adam Mohamed, Ahmed Ali Salad (Tako), Mahad Mohamed Salad. Guarator: Abdullahi Godah Barre Third parties Witnesses EU Special Envoy for Somalia, Amb. Michele Cervone; IGAD Special Envoy for Somalia, Amb. Muhammed Affey; UNISOM Special Representative to Secretary-General, Amb. Nicholas Kay; African Union, The Acting Special Representative and Deputy Special Representative of the Chairperson of African Union Commission, Hon. Lydia Wanyoto Mutende. Description Agreement sets forth principles for forming a new regional administration in the central part of Somalia. Agreement document SO_140730_CentralRegionFormation.pdf [] Local agreement properties Process type Formal structured process Explain rationale This agreement was concluded with the support of the Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) which invited the parties to Mogadishu. EU, IGAD, UN, and AU representatives signed as witnesses. The FGS mediated a similar agreement about a month earlier (Agreement: An Inclusive Interim Administration for the South West Regions of Somalia (Bay, Bakol and Lower Shabelle), 22/06/2014). Is there a documented link Yes to a national peace process? Link to national process: The agreement is part of a wider political settlement process in Somalia that aimed at establishing articulated rationale inclusive regional administrations.