The Evidence from Knossos on the Minoan Calendar G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Greek Vessels Pattern and Image

ANCIENT GREEK VESSELS PATTERN AND IMAGE 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is my pleasure to acknowledge the many individuals who helped make this exhibition possible. As the first collaboration between The Trout Gallery at Dickinson College and Bryn Mawr and Wilson Colleges, we hope that this exhibition sets a precedent of excellence and substance for future collaborations of this sort. At Wilson College, Robert K. Dickson, Associate Professor of Fine Art and Leigh Rupinski, College Archivist, enthusiasti- cally supported loaning the ancient Cypriot vessels seen here from the Barron Blewett Hunnicutt Classics ANCIENT Gallery/Collection. Emily Stanton, an Art History Major, Wilson ’15, prepared all of the vessels for our initial selection and compiled all existing documentation on them. At Bryn Mawr, Brian Wallace, Curator and Academic Liaison for Art and Artifacts, went out of his way to accommodate our request to borrow several ancient Greek GREEK VESSELS vessels at the same time that they were organizing their own exhibition of works from the same collection. Marianne Weldon, Collections Manager for Special Collections, deserves special thanks for not only preparing PATTERN AND IMAGE the objects for us to study and select, but also for providing images, procuring new images, seeing to the docu- mentation and transport of the works from Bryn Mawr to Carlisle, and for assisting with the installation. She has been meticulous in overseeing all issues related to the loan and exhibition, for which we are grateful. At The Trout Gallery, Phil Earenfight, Director and Associate Professor of Art History, has supported every idea and With works from the initiative that we have proposed with enthusiasm and financial assistance, without which this exhibition would not have materialized. -

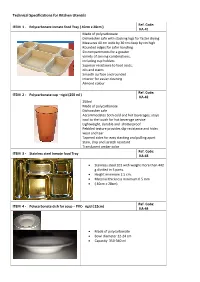

Technical Specifications for Kitchen Utensils

Technical Specifications for Kitchen Utensils Ref. Code: ITEM 1 - Polycarbonate inmate food Tray ( 40cm x 28cm ) KA-41 Made of polycarbonate Dishwasher safe with stacking lugs for faster drying Measures 40 cm wide by 30 cm deep by cm high Rounded edges for safer handling Six compartments for a greater variety of serving combinations, including cup holders Superior resistance to food acids, oils and stains Smooth surface and rounded interior for easier cleaning Almond colour Ref. Code: ITEM 2 - Polycarbonate cup –rigid (250 ml ) KA-42 250ml Made of polycarbonate Dishwasher safe Accommodates both cold and hot beverages; stays cool to the touch for hot beverage service Lightweight, durable and shatterproof Pebbled texture provides slip-resistance and hides wear and tear Tapered sides for easy stacking and pulling apart Stain, chip and scratch resistant Translucent amber color Ref. Code: ITEM 3 - Stainless steel Inmate food Tray KA-43 • Stainless steel 201 with weight more than 442 g divided in 5 parts. • Height minimum 2.5 cm. • Material thickness minimum 0.5 mm • ( 40cm x 28cm) Ref. Code: ITEM 4 - Polycarbonate dish for soup – PVC- rigid ( 22cm) KA-44 • Made of polycarbonate • Bowl diameter 22-24 cm • Capacity 350-360 ml Ref. Code: ITEM 5 - Plastic dish for salad – PVC- rigid KA-45 • Made of polycarbonate • Bowl diameter 22-24 cm • Capacity 225-250 ml ITEM 6- Heavy Duty Frying-pan from ( 2 set of 6 pcs from the biggest until Ref. Code: the smallest size) KA-46 Set of 6 Pcs from the biggest until the smallest size) Size fir the biggest one : 30-035 x 15-19.0-15 x 2.5 6.0 • Weight: 0.6-1.5 kg • Material: stainless steel Ref. -

Greece • Crete • Turkey May 28 - June 22, 2021

GREECE • CRETE • TURKEY MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 Tour Hosts: Dr. Scott Moore Dr. Jason Whitlark organized by GREECE - CRETE - TURKEY / May 28 - June 22, 2021 May 31 Mon ATHENS - CORINTH CANAL - CORINTH – ACROCORINTH - NAFPLION At 8:30a.m. depart from Athens and drive along the coastal highway of Saronic Gulf. Arrive at the Corinth Canal for a brief stop and then continue on to the Acropolis of Corinth. Acro-corinth is the citadel of Corinth. It is situated to the southwest of the ancient city and rises to an elevation of 1883 ft. [574 m.]. Today it is surrounded by walls that are about 1.85 mi. [3 km.] long. The foundations of the fortifications are ancient—going back to the Hellenistic Period. The current walls were built and rebuilt by the Byzantines, Franks, Venetians, and Ottoman Turks. Climb up and visit the fortress. Then proceed to the Ancient city of Corinth. It was to this megalopolis where the apostle Paul came and worked, established a thriving church, subsequently sending two of his epistles now part of the New Testament. Here, we see all of the sites associated with his ministry: the Agora, the Temple of Apollo, the Roman Odeon, the Bema and Gallio’s Seat. The small local archaeological museum here is an absolute must! In Romans 16:23 Paul mentions his friend Erastus and • • we will see an inscription to him at the site. In the afternoon we will drive to GREECE CRETE TURKEY Nafplion for check-in at hotel followed by dinner and overnight. (B,D) MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 June 1 Tue EPIDAURAUS - MYCENAE - NAFPLION Morning visit to Mycenae where we see the remains of the prehistoric citadel Parthenon, fortified with the Cyclopean Walls, the Lionesses’ Gate, the remains of the Athens Mycenaean Palace and the Tomb of King Agamemnon in which we will actually enter. -

Bowl Round 5 Bowl Round 5 First Quarter

NHBB B-Set Bowl 2017-2018 Bowl Round 5 Bowl Round 5 First Quarter (1) The remnants of this government established the Republic of Ezo after losing the Boshin War. Two and a half centuries earlier, this government was founded after its leader won the Battle of Sekigahara against the Toyotomi clan. This government's policy of sakoku came to an end when Matthew Perry's Black Ships forced the opening of Japan through the 1854 Convention of Kanagawa. For ten points, name this last Japanese shogunate. ANSWER: Tokugawa Shogunate (or Tokugawa Bakufu) (2) Xenophon's Anabasis describes ten thousand Greek soldiers of this type who fought Artaxerxes II of Persia. A war named for these people was won by Hamilcar Barca and led to his conquest of Spain. Famed soldiers of this type include slingers from Rhodes and archers from Crete. Greeks who fought for Persia were, for ten points, what type of soldier that fought not for national pride, but for money? ANSWER: mercenary (prompt on descriptive answers) (3) The most prominent of the Townshend Acts not to be repealed in 1770 was a tax levied on this commodity. The Dartmouth, the Eleanor, and the Beaver carried this commodity from England to the American colonies. The Intolerable Acts were passed in response to the dumping of this commodity into a Massachusetts Harbor in 1773 by members of the Sons of Liberty. For ten points, identify this commodity destroyed in a namesake Boston party. ANSWER: tea (accept Tea Act; accept Boston Tea Party) (4) This location is the setting of a photo of a boy holding a toy hand grenade by Diane Arbus. -

Greek Pottery Gallery Activity

SMART KIDS Greek Pottery The ancient Greeks were Greek pottery comes in many excellent pot-makers. Clay different shapes and sizes. was easy to find, and when This is because the vessels it was fired in a kiln, or hot were used for different oven, it became very strong. purposes; some were used for They decorated pottery with transportation and storage, scenes from stories as well some were for mixing, eating, as everyday life. Historians or drinking. Below are some have been able to learn a of the most common shapes. great deal about what life See if you can find examples was like in ancient Greece by of each of them in the gallery. studying the scenes painted on these vessels. Greek, Attic, in the manner of the Berlin Painter. Panathenaic amphora, ca. 500–490 B.C. Ceramic. Bequest of Mrs. Allan Marquand (y1950-10). Photo: Bruce M. White Amphora Hydria The name of this three-handled The amphora was a large, two- vase comes from the Greek word handled, oval-shaped vase with for water. Hydriai were used for a narrow neck. It was used for drawing water and also as urns storage and transport. to hold the ashes of the dead. Krater Oinochoe The word krater means “mixing The Oinochoe was a small pitcher bowl.” This large, two-handled used for pouring wine from a krater vase with a broad body and wide into a drinking cup. The word mouth was used for mixing wine oinochoe means “wine-pourer.” with water. Kylix Lekythos This narrow-necked vase with The kylix was a drinking cup with one handle usually held olive a broad, relatively shallow body. -

A Standard for Pottery Analysis in Archaeology

A Standard for Pottery Analysis in Archaeology Medieval Pottery Research Group Prehistoric Ceramics Research Group Study Group for Roman Pottery Draft 4 October 2015 CONTENTS Section 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Aims 1 1.2 Scope 1 1.3 Structure 2 1.4 Project Tasks 2 1.5 Using the Standard 5 Section 2 The Standard 6 2.1 Project Planning 6 2.2 Collection and Processing 8 2.3 Assessment 11 2.4 Analysis 13 2.5 Reporting 17 2.6 Archive Creation, Compilation and Transfer 20 Section 3 Glossary of Terms 23 Section 4 References 25 Section 5 Acknowledgements 27 Appendix 1 Scientific Analytical Techniques 28 Appendix 2 Approaches to Assessment 29 Appendix 3 Approaches to Analysis 33 Appendix 4 Approaches to Reporting 39 1. INTRODUCTION Pottery has two attributes that lend it great potential to inform the study of human activity in the past. The material a pot is made from, known to specialists as the fabric, consists of clay and inclusions that can be identified to locate the site at which a pot was made, as well as indicate methods of manufacture and date. The overall shape of a pot, together with the character of component parts such as rims and handles, and also the technique and style of decoration, can all be studied as the form. This can indicate when and how a pot was made and used, as well as serving to define cultural affinities. The interpretation of pottery is based on a detailed characterisation of the types present in any group, supported by sound quantification and consistent approaches to analysis that facilitate comparison between assemblages. -

Heraklion (Greece)

Research in the communities – mapping potential cultural heritage sites with potential for adaptive re-use – Heraklion (Greece) The island of Crete in general and the city of Heraklion has an enormous cultural heritage. The Arab traders from al-Andalus (Iberia) who founded the Emirate of Crete moved the island's capital from Gortyna to a new castle they called rabḍ al-ḫandaq in the 820s. This was Hellenized as Χάνδαξ (Chándax) or Χάνδακας (Chándakas) and Latinized as Candia, the Ottoman name was Kandiye. The ancient name Ηράκλειον was revived in the 19th century and comes from the nearby Roman port of Heracleum ("Heracles's city"), whose exact location is unknown. English usage formerly preferred the classicizing transliterations "Heraklion" or "Heraclion", but the form "Iraklion" is becoming more common. Knossos is located within the Municipality of Heraklion and has been called as Europe's oldest city. Heraklion is close to the ruins of the palace of Knossos, which in Minoan times was the largest centre of population on Crete. Knossos had a port at the site of Heraklion from the beginning of Early Minoan period (3500 to 2100 BC). Between 1600 and 1525 BC, the port was destroyed by a volcanic tsunami from nearby Santorini, leveling the region and covering it with ash. The present city of Heraklion was founded in 824 by the Arabs under Abu Hafs Umar. They built a moat around the city for protection, and named the city rabḍ al-ḫandaq, "Castle of the Moat", Hellenized as Χάνδαξ, Chandax). It became the capital of the Emirate of Crete (ca. -

British School at Athens Newsletter

The British School at Athens December an institute for advanced research 2018 From the Director It is a great pleasure to wish everyone a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year with this fourth issue of our newsletter offering up to date news of our activities to all who share our passion for study of the Hellenic world in all aspects and all periods. A year ago I wrote that ‘[t]he wall John Bennet (L) around our premises is a highly porous welcomes visitors, including HMA Kate membrane, through which many Smith (R) to the pass…’. At that time I could hardly have BSA as part of ‘The imagined that we would be looking British Open Day’ back on how that ‘porosity’ allowed 6,500 to visit our garden between Both these collaborations received are available to view on our recently mid-September and mid-November positive media coverage and raised the redesigned website. to experience the NEON organisation’s BSA’s profile here in Athens considerably. The website redesign is part of our City Project 2018 ‘Prosaic Origins’, an Alongside these events, our regular Development programme, about which exhibition of sculpture by Andreas programme in Athens and the UK there is more below, including a reminder Lolis. The sense of loss generated by continued. One highlight for me was a of how to sign up to our new tiered sup- what now seem like empty spaces is performance at the BSA of the Odyssey — porter structure in effect from 1 January mitigated by the knowledge that a in two hours — by UK-based storytellers 2019. -

1 Political Geography and Palatial Crete Andrew Bevan Postprint Of

Political geography and palatial Crete Andrew Bevan Postprint of 2010 paper in Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 23.1: 27-54 (doi: 10.1558/jmea.v23i1.27). Abstract The political geography of Crete during the period of the Bronze Age palaces has been a subject of widespread debate, not only with respect to the timing of the island’s move towards greater social and political complexity, but also with regard to the nature of the political institutions and territorial configurations that underpinned palace-centred society, as well as their longer-term stability over the course of the 2nd millennium BC. As such, the region provides an ideal context in which to consider the broader question of how we develop robust political geographies in pre- and proto-historic contexts. This paper proposes the need for a more deliberate interlocking of computational, comparative and material approaches, as a means of guiding our political model-building efforts. 1. Introduction While the world of palatial Crete has no foundational story as powerful or as enduring as the Trojan war, the Classical tradition nonetheless invokes the Cretan palatial past in conveniently clear-cut ways, referring to a central mythical figure of King Minos alongside stories of political unification, law- giving, overseas expansion, thalassocracy, internecine struggle and eventual political re-fragmentation (e.g. Homer Odyssey 19.165-202; Herodotus Histories 1.171-3, 3.122; Thucydides Peloponnesian War 1.4-8; Aristotle Politics 2.10; also Pseudo-Apollodorus Bibliotheca 3.1-3). More precisely, such sources assume the development of a single state under a male king whose core political borders encompassed all of Crete and whose wider political control by indirect governance eventually extended to at least some of the Aegean islands. -

Tableware Fiber Blend

www.earthchoicepackaging.com Tableware Fiber Blend Social responsibility, respect and care for the environment require action in today’s world, while keeping an eye on the future. These products are made from trees and other renewable plant-based materials. Fiber (paper) material Soak through resistant design • Made of a blend of bagasse (sugar cane), • Resists grease, moisture and helps bamboo and wood fibers, which are eliminate messy leaks renewable resources. Compostable Strong • Many SKUs meet ASTM D6868 • Offers durable construction for multi-food compostability standard and are applications compostable in commercial facilities, which may not exist in all areas. Not suitable for home composting. www.earthchoicepackaging.com Tableware Pactiv Item MC500120001 Pactiv Item MC500160001 Pactiv Item MC500060001 Pactiv Item MC500070001 ® 6.75” Placesetter® 12 oz. Placesetter® 16 oz. Placesetter® 6” Placesetter Description Description Description Preferred™ Snack Description Preferred™ Snack Preferred™ Bowl Preferred™ Bowl Plate Plate Case Cube 2.1 Case Cube 2.73 Case Cube 1.3 Case Cube 2.1 Case Wt. 23.5 Case Wt. 27.9 Case Wt. 16.7 Case Wt. 20.2 Case Pack 1000 Case Pack 1000 Case Pack 1000 Case Pack 1000 Pactiv Item YMC500090002 Pactiv Item YMC500110002 Pactiv Item MC500440002 Pactiv Item MC500100002 ® 8.75” Placesetter® 10” Placesetter® ® 8.75” Placesetter ™ 10” Placesetter Description ™ Description Preferred Description Preferred Description Preferred Plate 3-Cmpt. Platel 3-Cmpt. Plate Preferred Plate Case Cube 1.34 Case Cube 1.23 Case Cube 2.5 Case Cube 1.3 Case Wt. 18.0 Case Wt. 18.0 Case Wt. 24.6 Case Wt. 24.64 Case Pack 500 Case Pack 500 Case Pack 500 Case Pack 500 Pactiv Item MC500430001 Pactiv Item YMC500470001 Pactiv Item MF500100000 Pactiv Item MF500440000 7.5” x 10” 9.875” x 12.5” EarthChoice 10” EarthChoice 10”/3 Placesetter® Placesetter® Description Description cmpt fiber plate Description Preferred Oval Description Preferred Oval fiber plate USA USA Platter Platter Case Cube 1.8 Case Cube 2.5 Case Cube 1.3 Case Cube 2.30 Case Wt. -

Superior ® Versatile Dinnerware

2019 Products available through US Foods Culinary Equipment & Supplies®. To place an order, log on to your US Foods Online account, or contact your US Foods sales representative. Please allow up to 10 business days for delivery. LUNA™ ASH NEW Platter Rectangular Platter Platter Square Plate Plate 7551483 & 6120213 6045977 & 5666989 9135126 & 3861578 5442209 & 2909804 3521079, 7917790, 6342293, 8338387 & 3085224 Bowl Pasta/Rim Soup Bowl Nappie Bowl Saucer Cup 6603050 & 9052116 5269760 3777696 3859995 5566139 & 2020969 LUNA ASH SPECKLE COLORS, ROUND, SQUARE & ORGANIC A-CODE DESCRIPTION PACK SIZE MFR# 7551483 Platter, 12 ½" x 6 ½" 12 LU-14-AS 6120213 Platter, 10" x 5 ½" 24 LU-12-AS 6045977 Rectangular Platter, 13" x 6 ½" 12 LU-133-AS 5666989 Rectangular Platter, 6" x 4" 36 LU-64-AS Bouillon Salt & Pepper 9135126 Platter, 13 ¼" x 9 ¼" 12 LU-139-AS 4798836 8638952 3861578 Platter, 11½" x 8" 12 LU-118-AS 5442209 Square Plate, 10" 12 LU-22-AS 2909804 Square Plate, 7" 24 LU-77-AS 3521079 Plate, 12" 12 LU-21-AS 7917790 Plate, 10 ½" 12 LU-16-AS 6342293 Plate, 9" 12 LU-8-AS 8338387 Plate, 7" 24 LU-7-AS 3085224 Plate, 5 ½" 36 LU-5-AS 6603050 Bowl, 14 oz, 9" x 4 ½" 12 LU-44-AS Sugar Container Sauce Dish 9052116 Bowl, 7oz, 7" x 4 ½" 24 LU-43-AS 9310306 9318713 5566139 Pasta/Rim Soup, 48 oz, 10 ½" 12 LU-120-AS 2020969 Pasta/Rim Soup, 20 oz, 8 ½" 12 LU-3-AS 5269760 Nappie Bowl, 14 oz, 5 ¼" 12 LU-18-AS 3777696 Saucer, 5 ¾" 24 LU-2-AS 3859995 Cup, 9 oz, 3 ¾" 24 LU-1-AS 8638952 Salt & Pepper Shakers, 2.5oz 24 LU-101-AS 4798836 Bouillon, 9 oz, 3 ¾" 24 LU-4-AS -

The Guide Cookware Bakeware

THE GUIDE TO COOKWARE AND BAKEWARE HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE This guide is organized primarily for retail buyers and knowledgeable consumers as an easy- reference handbook and includes as much information as possible. The information carries readers from primitive cooking through to today’s use of the most progressive technology in manufacturing. Year after year, buyers and knowledgeable consumers find this guide to be an invaluable tool in selection useful desirable productions for those who ultimately will use it in their own kitchens. Consumers will find this guide helpful in learning about materials and methods used in the making of cookware. Such knowledge leads to the selection of quality equipment that can last a lifetime with sound care and maintenance, information that is also found within this guide. Any reader even glancing through the text and illustrations will gain a better appreciation of one of the oldest and most durable products mankind has every devised. SECTIONS • Cooking Past and Present ........................................ 3 • Cooking Methods ................................................ 5 • Materials and Construction ....................................... 8 • Finishes, Coatings & Decorations ................................. 15 • Handles, Covers & Lids ........................................... 22 • Care & Maintenance ............................................. 26 • Selection Products ............................................... 30 • CMA Standards .................................................. 31 •