Texas Latino Voters Study Slides Deck

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesbian and Gay Music

Revista Eletrônica de Musicologia Volume VII – Dezembro de 2002 Lesbian and Gay Music by Philip Brett and Elizabeth Wood the unexpurgated full-length original of the New Grove II article, edited by Carlos Palombini A record, in both historical documentation and biographical reclamation, of the struggles and sensi- bilities of homosexual people of the West that came out in their music, and of the [undoubted but unacknowledged] contribution of homosexual men and women to the music profession. In broader terms, a special perspective from which Western music of all kinds can be heard and critiqued. I. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL VERSION 1 II. (HOMO)SEXUALIT Y AND MUSICALIT Y 2 III. MUSIC AND THE LESBIAN AND GAY MOVEMENT 7 IV. MUSICAL THEATRE, JAZZ AND POPULAR MUSIC 10 V. MUSIC AND THE AIDS/HIV CRISIS 13 VI. DEVELOPMENTS IN THE 1990S 14 VII. DIVAS AND DISCOS 16 VIII. ANTHROPOLOGY AND HISTORY 19 IX. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 24 X. EDITOR’S NOTES 24 XI. DISCOGRAPHY 25 XII. BIBLIOGRAPHY 25 I. INTRODUCTION TO THE ORIGINAL VERSION 1 What Grove printed under ‘Gay and Lesbian Music’ was not entirely what we intended, from the title on. Since we were allotted only two 2500 words and wrote almost five times as much, we inevitably expected cuts. These came not as we feared in the more theoretical sections, but in certain other tar- geted areas: names, popular music, and the role of women. Though some living musicians were allowed in, all those thought to be uncomfortable about their sexual orientation’s being known were excised, beginning with Boulez. -

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC San Diego UC San Diego Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Experimental Music: Redefining Authenticity Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3xw7m355 Author Tavolacci, Christine Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Experimental Music: Redefining Authenticity A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Musical Arts in Contemporary Music Performance by Christine E. Tavolacci Committee in charge: Professor John Fonville, Chair Professor Anthony Burr Professor Lisa Porter Professor William Propp Professor Katharina Rosenberger 2017 Copyright Christine E. Tavolacci, 2017 All Rights Reserved The Dissertation of Christine E. Tavolacci is approved, and is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2017 iii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my parents, Frank J. and Christine M. Tavolacci, whose love and support are with me always. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page.……………………………………………………………………. iii Dedication………………………..…………………………………………………. iv Table of Contents………………………..…………………………………………. v List of Figures….……………………..…………………………………………….. vi AcknoWledgments….………………..…………………………...………….…….. vii Vita…………………………………………………..………………………….……. viii Abstract of Dissertation…………..………………..………………………............ ix Introduction: A Brief History and Definition of Experimental Music -

Battles Around New Music in New York in the Seventies

Presenting the New: Battles around New Music in New York in the Seventies A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Joshua David Jurkovskis Plocher IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY David Grayson, Adviser December 2012 © Joshua David Jurkovskis Plocher 2012 i Acknowledgements One of the best things about reaching the end of this process is the opportunity to publicly thank the people who have helped to make it happen. More than any other individual, thanks must go to my wife, who has had to put up with more of my rambling than anybody, and has graciously given me half of every weekend for the last several years to keep working. Thank you, too, to my adviser, David Grayson, whose steady support in a shifting institutional environment has been invaluable. To the rest of my committee: Sumanth Gopinath, Kelley Harness, and Richard Leppert, for their advice and willingness to jump back in on this project after every life-inflicted gap. Thanks also to my mother and to my kids, for different reasons. Thanks to the staff at the New York Public Library (the one on 5th Ave. with the lions) for helping me track down the SoHo Weekly News microfilm when it had apparently vanished, and to the professional staff at the New York Public Library for Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, and to the Fales Special Collections staff at Bobst Library at New York University. Special thanks to the much smaller archival operation at the Kitchen, where I was assisted at various times by John Migliore and Samara Davis. -

Helsingin Kaupunginteatteri

HELSINGIN KAUPUNGINTEATTERI Luettelo esityksistä on ensi-iltajärjestyksessä. Tiedot perustuvat esitysten käsiohjelmiin. Voit etsiä yksittäisen esityksen nimeä lukuohjelmasi hakutoiminnolla (yleensä ctrl-F) Walentin Chorell: Sopulit (Lemlarna) Suomennos: Marja Rankkala Ensi-ilta 9.9.1965 Vallila Esityskertoja: 13 Ohjaus: Sakari Puurunen & Kalle Holmberg Ohjaajan assistentti: Ritva Siikala Lavastus: Lassi Salovaara Puvut: Elsa Pättiniemi Musiikki: Ilkka Kuusisto Valokuvaaja: Pentti Auer HENKILÖT: Käthi: Elsa Turakainen/ Lise: Eila Rinne/ Tabitha: Hillevi Lagerstam/ Paula: Pirkko Peltomäki/ Muukalainen: Hannes Häyrinen/ Johann: EskoMannermaa/ Peter: Eero Keskitalo/ Äiti: Tiina Rinne/ Ilse: Heidi Krohn/ Wilhelm: Veikko Uusimäki/ Pappi: Uljas Kandolin/ Günther: Kalevi Kahra/ Tauno Kajander/ Leo Jokela/ Arto Tuominen/ Sakari Halonen/ Stig Fransman/ Elina Pohjanpää/ Marjatta Kallio/ Marja Rankkala: Rakkain rakastaja Ensi-ilta:23.9.1965 YO-talo Esityskertoja: 20 Ohjaus: Ritva Arvelo Apulaisohjaaja: Kurt Nuotio Lavastus ja puvut: Leo Lehto Musiikki: Arthur Fuhrmann Valokuvaaja: Pentti Auer HENKILÖT: Magdalena Desiria: Anneli Haahdenmaa/ Magdalena nuorena: Anja Haahdenmaa/ Ella: Martta Kontula/ Jolanda: Enni Rekola/ David: Oiva Sala/ Alfred: Aarre Karén/ “Karibian Konsuli”: Leo Lähteenmäki/ Rikhard: Kullervo Kalske/ Rafael: Sasu Haapanen/ Ramon: Viktor Klimenko/ Daniel: Jarno Hiilloskorpi/ Pepe: Helmer Salmi/ Anne: Eira Karén/ Marietta: Marjatta Raita/ Tuomari: Veikko Linna/ Tanssiryhmä: Marjukka Halttunen, Liisa Huuskonen, Rauni Jakobsson, Ritva -

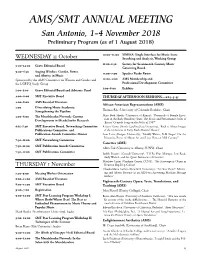

Program (As of 1 August 2018)

AMS/SMT ANNUAL MEETING San Antonio, 1–4 November 2018 Preliminary Program (as of 1 August 2018) 10:00–12:00 SIMSSA: Single Interface for Music Score WEDNESDAY 31 October Searching and Analysis, Working Group 11:00–1:30 Society for Seventeenth-Century Music 9:00–12:00 Grove Editorial Board Governing Board 9:00–6:30 Staging Witches: Gender, Power, 11:00–7:00 Speaker Ready Room and Alterity in Music Sponsored by the AMS Committee on Women and Gender and 12:00–2:00 AMS Membership and the LGBTQ Study Group Professional Development Committee 1:00–8:00 Exhibits 1:00–5:00 Grove Editorial Board and Advisory Panel 2:00–6:00 SMT Executive Board THURSDAY AFTERNOON SESSIONS—2:15–3:45 2:00–8:00 AMS Board of Directors African-American Representations (AMS) 3:00 Diversifying Music Academia: Strengthening the Pipeline Thomas Riis (University of Colorado Boulder), Chair 3:00–6:00 The Mendelssohn Network: Current Mary Beth Sheehy (University of Kansas), “Portrayals of Female Exoti- Developments in Mendelssohn Research cism in the Early Broadway Years: The Music and Performance Styles of ‘Exotic’ Comedy Songs in the Follies of 1907” 6:15–7:30 SMT Executive Board, Networking Committee, Kristen Turner (North Carolina State University), “Back to Africa: Images Publications Committee, and of the Continent in Early Black Musical Theater” Publication Awards Committee Dinner Sean Lorre (Rutgers University), “Muddy Waters, Folk Singer? On the Discursive Power of Album Art and Liner Notes at Mid-Century” 7:30–11:00 SMT Networking Committee Cassettes (AMS) 7:30–11:00 -

Beethoven Was a Lesbian a Tribute to Pauline Oliveros

THEMEGUIDE Beethoven “I’m not dismissive of classical music Was a Lesbian and the Western canon. It’s simply that I can’t be bound by it. I’ve been A Tribute to jumping out of categories all my life.” PAULINE OLIVEROS —Pauline Oliveros Sunday, October 29, 2017, from 4 to 7 p.m. ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries KNOW BEFORE YOU GO o Pauline Oliveros (1932–2016) was one of the foremost avant-garde composers and musical thinkers of her generation. o She expanded our understanding of sound, experimented with new musical forms, and encouraged non-hierarchical forms of collaboration. She worked in electronic music and other experimental musical forms, first as a composer and later as an improviser and collaborative listener. o Beyond the music scene, she was influential in the broader arts community and 1970s women’s movement in Southern California. o The title Beethoven Was a Lesbian comes from a 1974 collaboration between Oliveros and Alison Knowles that addressed women’s outsider status in the music world. o This event will feature the poet/playwright/director/Deep Listener Ione and the International Contemporary Ensemble. THE MANY INNOVATIONS, INTERVENTIONS, AND INSPIRATIONS OF PAULINE OLIVEROS Pauline Oliveros was an experimental musician in the most expansive senses of both terms. She expanded the definition and possibilities of music. She also expanded conceptions about who makes music and the relationships between music, society, and our shared world. To give just a peek at her numerous innovations, interventions, and inspirations: o In 1965, Oliveros made a piece called Bye Bye Butterfly, using oscillators and tape delay to manipulate and augment a recording of the opera Madama Butterfly. -

A Festival of Unexpected New Music February 28March 1St, 2014 Sfjazz Center

SFJAZZ CENTER SFJAZZ MINDS OTHER OTHER 19 MARCH 1ST, 2014 1ST, MARCH A FESTIVAL FEBRUARY 28 FEBRUARY OF UNEXPECTED NEW MUSIC Find Left of the Dial in print or online at sfbg.com WELCOME A FESTIVAL OF UNEXPECTED TO OTHER MINDS 19 NEW MUSIC The 19th Other Minds Festival is 2 Message from the Executive & Artistic Director presented by Other Minds in association 4 Exhibition & Silent Auction with the Djerassi Resident Artists Program and SFJazz Center 11 Opening Night Gala 13 Concert 1 All festival concerts take place in Robert N. Miner Auditorium in the new SFJAZZ Center. 14 Concert 1 Program Notes Congratulations to Randall Kline and SFJAZZ 17 Concert 2 on the successful launch of their new home 19 Concert 2 Program Notes venue. This year, for the fi rst time, the Other Minds Festival focuses exclusively on compos- 20 Other Minds 18 Performers ers from Northern California. 26 Other Minds 18 Composers 35 About Other Minds 36 Festival Supporters 40 About The Festival This booklet © 2014 Other Minds. All rights reserved. Thanks to Adah Bakalinsky for underwriting the printing of our OM 19 program booklet. MESSAGE FROM THE ARTISTIC DIRECTOR WELCOME TO OTHER MINDS 19 Ever since the dawn of “modern music” in the U.S., the San Francisco Bay Area has been a leading force in exploring new territory. In 1914 it was Henry Cowell leading the way with his tone clusters and strumming directly on the strings of the concert grand, then his students Lou Harrison and John Cage in the 30s with their percussion revolution, and the protégés of Robert Erickson in the Fifties with their focus on graphic scores and improvisation, and the SF Tape Music Center’s live electronic pioneers Subotnick, Oliveros, Sender, and others in the Sixties, alongside Terry Riley, Steve Reich and La Monte Young and their new minimalism. -

C.V. One Page

Jonathan Benjamin Myers 205 Seaview Ave., Santa Cruz, CA 95062 [email protected] | 617-650-3307 Education 2016— University of California at Santa Cruz D.M.A. in Music Composition 2012—2014 Mills College M.A. in Music Composition 2007—2011 Wesleyan University B.A. with High Honors in Music Honors 2016-17 Regents Fellowship, University of California at Santa Cruz 2015 Orkest de Ereprijs: Young Composers Meeting Finalist [Netherlands] for Flocking 2013 Performing Indonesia: Conference/Festival of Music, Dance, and Drama Diffusion premiered at Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C. 2013 Now Hear Ensemble [Santa Barbara] Made in California project Mobile commissioned for performance and recording 2011 Gwen Livingston Pokora Prize, Wesleyan University awarded to the outstanding undergraduate in music composition Selected Professional Experience 2018 Instructor of Record for History, Literature, and Technology of Electronic Music; Workshop in Electronic Music. 2017-2018 Teaching Assistant for Laptop Music, Electronic Music; Music of the Beatles; Artificial Intelligence in Music; Advanced Music Theory; History of Rap and Hip Hop; Laptop Music; Psychophysics of Music; at UCSC, Santa Cruz, CA 2016 Administrator / Coordinator for the S.E.M. Ensemble, Brooklyn, NY 2014 Stage Manager for Littlefield Concert Hall, Mills College, Oakland, CA Major Teachers Composition with Larry Polansky (UCSC), David Dunn (UCSC), Zeena Parkins (Mills), James Fei (Mills), Chris Brown (Mills), Anthony Braxton (Wesleyan), Alvin Lucier (Wesleyan). Performance with Roscoe Mitchell (improvisation), William Winant (percussion), Pheeroan AkLaff (percussion), Tyshawn Sorey (percussion), Abraham Adzenyah (West African drumming), I.M. Harjito (Javanese Gamelan) Masterclass/workshop participation with Louis Andriessen, Martijn Padding, George Lewis, Nicolas Collins, Laurie Anderson, Pauline Oliveros, David Behrman.. -

Regional Oral History Office University of California the Bancroft Library Berkeley, California

Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Pauline Oliveros IMPROVISATION, DEEP LISTENING AND FLUMMOXING THE HIERACHY Interviews conducted by Caroline Crawford in 2000 Copyright © 2006 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Pauline Oliveros, dated October 26, 2000. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

2013 DL Art Science Conference Program.Pdf

Across Boundaries, Across Abilities Deep Listening Institute, Ltd. 77 Cornell St, Suite 303 PO Box 1956 Kingston, NY 12401 www.deeplistening.org [email protected] facebook.com/deep.listener Twitter @DeepListening What is Deep Listening? There’s more to listening than meets the ear. Pauline Oliveros describes Deep Listening as “listening in every possible way to everything possible to hear no matter what one is doing.” Basically Deep Listening, as developed by Oliveros, explores the difference between the involuntary nature of hearing and the voluntary, selective nature – exclusive and inclusive -- of listening. The practice includes bodywork, sonic meditations, interactive performance, listening to the sounds of daily life, nature, one’s own thoughts, imagination and dreams, and listening to listening itself. It cultivates a heightened awareness of the sonic environment, both external and internal, and promotes experimentation, improvisation, collaboration, playfulness and other creative skills vital to personal and community growth. ; 2 Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center (EMPAC) Troy, New York My hope is to inspire scientific inquiry and research on listening as well as to bring the world community together to share ideas and practice Deep Listening. --Pauline Oliveros, Founder of Deep Listening Institute Dear Conference Attendees, I am extremely pleased to welcome you to Deep Listening: Art/Science, the First International Conference on Deep Listening! This three-day event will feature an amazing array of lectures, workshops, posters and experience-focused presentations on a number of topics related to the art and science of listening. This includes many distinguished and long-time members of the Deep Listening community as well as a host of scholars and creators who approach listening from unique perspectives. -

Wisdom of the Impulse on the Nature of Musical Free Improvisation Part 1

Wisdom of the Impulse On the Nature of Musical Free Improvisation Part 1 Tom Nunn © 1998 Pdf edition, 2004 ISBN 87-91425-02-6 (Part1) For technical reasons, the document had to be divided into two parts. Please see continuation in Part 2. PUBLISHER's NOTE This pdf freeware edition was made for the website International Improvised Music Archive (IIMA) in agreement with the author on the basis of the printed book and its data files. There are no changes in the contents, however there are some adjustments for technical reasons. Footnotes have been integrated into the text to avoid any navigation problems. Please be advised that page numbers do not match the printed edition and that some details differ, as slight changes to available files were made by the author before printing. An index has been preserved here as Appendix D without the page numbers. Carl Bergstroem-Nielsen. CONTENTS [The reader is advised to use the bookmarks for navigating within the text - this can, however, serve as an overview. Please note that you must have both Part 1 and Part 2 to be able to view the entire document.] [Part 1:] PREFACE CHAPTER 1. PURPOSE AND APPROACH Purpose Approach CHAPTER 2. ORIGINS OF THE PRACTICE Improvisation in the History of Western Classical Music Sources Jazz Jazz Since 1960 Relationship of Jazz to Free Improvisation New Music and the Evolution of Free Improvisation Improvisation, Chance and Indeterminacy The Evolution of Free Improvisation as a Practice Conclusion CHAPTER 3. TERMINOLOGY Terms Free Improvisation Sound Influence Context Impulse Improvisational Milieu Content Linear Functions Identities Relational Functions Transitions Gestural Continuity/Integrity Segmental Form Meta-Style Contextualization Projection Flow Perception Impression CHAPTER 4. -

Brian Eno • • • His Music and the Vertical Color of Sound

BRIAN ENO • • • HIS MUSIC AND THE VERTICAL COLOR OF SOUND by Eric Tamm Copyright © 1988 by Eric Tamm DEDICATION This book is dedicated to my parents, Igor Tamm and Olive Pitkin Tamm. In my childhood, my father sang bass and strummed guitar, my mother played piano and violin and sang in choirs. Together they gave me a love and respect for music that will be with me always. i TABLE OF CONTENTS DEDICATION ............................................................................................ i TABLE OF CONTENTS........................................................................... ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ....................................................................... iv CHAPTER ONE: ENO’S WORK IN PERSPECTIVE ............................... 1 CHAPTER TWO: BACKGROUND AND INFLUENCES ........................ 12 CHAPTER THREE: ON OTHER MUSIC: ENO AS CRITIC................... 24 CHAPTER FOUR: THE EAR OF THE NON-MUSICIAN........................ 39 Art School and Experimental Works, Process and Product ................ 39 On Listening........................................................................................ 41 Craft and the Non-Musician ................................................................ 44 CHAPTER FIVE: LISTENERS AND AIMS ............................................ 51 Eno’s Audience................................................................................... 51 Eno’s Artistic Intent ............................................................................. 55 “Generating and Organizing Variety in