The New Mental Disorder Defences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fergus Whyte | Arnot Manderson Advocates

[email protected] 07572 945 963 Year of Call FERGUS WHYTE 2020 Devil Masters Usman Tariq Ross McClelland Frances Connor @WhyteFergus on Twitter LinkedIn Profile Practice Profile Fergus is an experienced litigator with an interest in commercial and public law disputes, intellectual property, data protection and media law, trust law and alternative dispute resolution. He has considerable experience in courtroom advocacy as well as experience in conducting complex litigation, dealing with expert evidence and managing client relationships. Fergus transferred to the Scottish bar in June 2020 having previously been a barrister and solicitor in New Zealand (since 2012) and having completed an LLM at the University of Edinburgh and the Faculty of Advocates examinations in Scots Law. Since calling he has acted in a commercial matter in the Outer House as sole counsel as well as appearing as a junior in the Inner House, and conducted a number of proceedings before Sheriffs. He has also recently appeared as junior counsel in an arbitration under the Dubai International Arbitration Centre Rules relating to a construction dispute. He has a strong background in legal research and comparative law having acted as a judges' clerk (judicial assistant), in client and case management as a solicitor in a boutique litigation firm and as an advocate before the higher courts in New Zealand. He has worked in a number of legal roles in Scotland including as a researcher to the Edinburgh Tram Inquiry. Fergus is an associate member of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators and a former coach of the University of Edinburgh Vis Moot Team. -

Nicola Gilchrist | Arnot Manderson Advocates

[email protected] 07884 060508 Year of Call NICOLA GILCHRIST 2011 Devil Masters Kate Dowdalls QC Gavin McColl QC Shelagh McCall QC @NicolaGilchrist on Twitter LinkedIn Profile Practice Profile Nicola is recommended in both the Chambers & Partners UK Bar and The Legal 500 UK Bar guides. Nicola specialises in family and child law, and is regularly involved in cases in the Court of Session and Sheriff Courts both in cases at first instance and in appeals to the Sheriff Appeal Court and the Inner House. She has experience across the board in litigation concerning divorce, financial provision, cohabitation and civil partnerships. Her expertise in child law encompasses all of its many facets, including complex jurisdictional issues, international child abduction, permanence orders and petitions for adoption. She has a particular interest in cases that involve sensitive cross-cultural issues, domestic abuse and matters affecting women and girls. She successfully appeared in the first forced marriage case to be heard in Scotland. Nicola was appointed as an Advocate Depute (Ad Hoc) in 2015 and she has been instructed as junior counsel in a number of criminal trials and has appeared in the High Court of Justiciary and in the Criminal Appeal Court for both the Crown and the Appellant. Nicola was appointed as a lead statement taker at the Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry in 2016. Nicola is a director of Relationships Scotland. Education & Professional Career to Date Trainee Solicitor - Balfour & Manson Solicitor - MMS Solicitor - HBJ -

Judicial Interpretation of the Scottish Juvenile Justice System: Fostering Or Frustrating the Welfare Model? Barbara A

Boston College International and Comparative Law Review Volume 8 | Issue 2 Article 4 8-1-1985 Judicial Interpretation of the Scottish Juvenile Justice System: Fostering or Frustrating the Welfare Model? Barbara A. Cardone Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/iclr Part of the Juvenile Law Commons Recommended Citation Barbara A. Cardone, Judicial Interpretation of the Scottish Juvenile Justice System: Fostering or Frustrating the Welfare Model?, 8 B.C. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 377 (1985), http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/iclr/vol8/iss2/4 This Notes is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Judicial Interpretation of the Scottish Juvenile Justice System: Fostering or Frustrating the Welfare Model? I. INTRODUCTION In 1961 the Secretary of State for Scotland 1 appointed the Honorable Lord Kilbrandon2 to chair a committee3 to evaluate the powers and procedures of the Scottish courts4 treating juvenile delinquents" and juveniles in need of care or protection.6 At the time of the Committee's formation,juvenile crime in Scotland 1. The Secretary of State for Scotland, a government minister, maintains various administrative responsibilities for Scottish affairs. Among the Secretary's duties are the administration of health, education, housing, roads, and the courts. Traditionally, the Secretary of State is always a member of the House of Commons. F.M. -

P906/20 List of Authorities for the Petitioner in Respect Of

1 IN THE COURT OF SESSION Court Ref: P906/20 LIST OF AUTHORITIES FOR THE PETITIONER IN RESPECT OF THE SINGLE BILLS HEARING in the PETITION of THE RIGHT HONOURABLE W. JAMES WOLFFE QC, HER MAJESTY’S ADVOCATE, Crown Office, 25 Chambers Street, Edinburgh, EH1 1LA PETITIONER for an order under section 100 of the Courts Reform (Scotland) Act 2014 Statutory provisions 1. Vexatious Actions (Scotland) Act 1898 2. Senior Courts Act 1981, section 42 3. Courts Reform (Scotland) Act 2014, sections 100-101 Court rules 4. Chapter 38 of the Rules of the Court of Session Cases 5. Lord Advocate v Cooney 1984 SLT 434 at 434 6. Attorney-General v Wentworth (1988) 14 NSWLR 481 at 492 7. Attorney General v Barker [2000] 2 WLUK 602, §19 8. Attorney General v Covey [2001] EWCA Civ 254, §56 9. Attorney-General v Collier [2001] NZAR 137, §36 10. Attorney General v Purvis [2003] EWHC 3190 (Admin), §29-§30 11. HM Advocate v Frost 2007 SC 215, §30 12. Lord Advocate v McNamara 2009 SC 598, §§8, 31-33, 36, 38, 40 13. Sans Souci Limited v VRL Services Limited [2012] UKPC 6, §13 14. Lord Advocate v Duffy [2013] CSIH 50, §37 15. Lord Advocate v Aslam [2019] CSIH 17, §§7-8, 10 16. Attorney General v Gayle-Childs [2020] EWHC 3811 (QB), §§27-28 1 Vexatious Actions (Scotland) Act 1898 c. 35 2 Vexatious Actions (Scotland) Act 1898 c. 35 Preamble Superseded Version 1 of 2 12 August 1898 - 27 November 2016 Subjects Civil procedure An Act to prevent vexatious Legal proceedings in Scotland. -

Many Members of the Scottish Legal Profession Were Surprised, Open

I!!!I SCOTTISH LEGAL EDUCATION AND THE LEGAL PROFESSION DAvID EDWARD Many members of the Scottish legal profession were surprised, open• ing their Scotsman on January 24, 1990, to find a centre-page article by Professor William Wilson entitled The Death Sentence for Scots Law. It began: "The Law Reform (Miscellaneous Provisions) (Scotland) Bill,pre• sently before parliament, should be titled the Scots Law (Abolition) Bill because that indicates its object and probable effect. Like all such bills, it is a cocktail:on top float a few cherries and bubbles-easier divorce, control of charities, licensing reform-which will no doubt attract most of parliaments's attention. "Under the surface, however, fulminates a toxic brew which may well prove fatal to the Scottish legal system and to the law of Scotland-the provisions which will alter the structure of the legal profession," Up to that time, Bill Wilson had not generally been seen as the doughtiest champion of the Scottish profession nor, in particular, of the Faculty of Advocates which, after completing his period of devil• ling, he decided at the last moment not to join. But there could be no doubt as to the authorship of this scathing philippic. No-one else could have written: "It seems surprising that we give an expensive education lasting several years to intending solicitors and advocates to equip them to appear in court, but, apparently, any Tom, Dick or Harry is to be able to come in off the street and give the judges the patter. It is a striking feature of the bill that it pays hardly -

Making Lawyers Moral? Ethical Codes and Moral Character

Tax evasion and the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 601 Making lawyers moral? Ethical codes and moral character Donald Nicolson* The Law School, University of Strathclyde This article argues that professional codes of conduct cannot perform the important task of ensuring that lawyers uphold high ethical standards. Instead, moral behaviour by lawyers requires the development of fixed behavioural attributes relevant to legal practice – what may be called a lawyer’s professional moral character. At the same time, however, along with other factors, professional codes are important in that they can either contribute to or detract from the successful development of professional moral character. If so, it is argued that in order to have the best chance of assisting the character development of lawyers, codes should neither take the form of highly detailed or extremely vague, aspirational norms, but should instead guide ethical decision-making by requiring them to consider a wide range of contextual factors when resolving ethical dilemmas. 1. INTRODUCTION To a large extent, access to justice, and the quality of law and the legal process is in the hands of legal practitioners who can (and frequently do) cause much harm in their professional activities.1 For example, treating law purely as a business can lead to citizens going unrepresented or being poorly represented. Conversely, overzealous representation and loyalty to clients may harm opponents, affected third parties, the administration of justice, and the general public interest. Accordingly, at least since the realisation that most Watergate miscreants were trained lawyers, professional legal ethics has been taught and academically debated in the United States. -

Haskell Memorial Master Class: Draft Lecture

Linda Haskell Memorial Master Class: 29 October 2010 Parent, child and community participation in child welfare decision-making. Is there room for lawyers? The unique Scottish experience of the Children's Hearings I am very pleased and honoured to be here today to deliver the Linda Haskell Memorial Master Class. It is especially poignant today as Mr. William Haskell, Linda’s father recently died. I also want to thank Professor Emilia Martinez-Brawley who jointly with the Haskell family invited me to Arizona to deliver this class. Thank you everyone for coming along today. Public intervention in the lives of troubled and troublesome children and young people presents fundamental and enduring challenges for policy, law and professional practice. Child welfare decision makers are required to balance the merits of intervention against non-intervention in often-complex cases where final outcomes for children’s welfare are not easily gauged. In youth justice decision-making, whilst the relative balance between justice and welfare-oriented responses in different jurisdictions remain contingent on socio-economic, cultural and historical factors, the challenge of just decision making for often-vulnerable children and young people remain. These challenges lie at the heart of all systems of child welfare and youth justice decision-making regardless of the nature of formal adjudicative structures. Today I am going to discuss the Scottish children’s hearing tribunals system, which takes a unique approach to these challenges. First, I will briefly outline the philosophy and origins of the system and the key features that differentiate children’s hearings from 1 juvenile courts, including the pivotal role of the lay tribunal. -

Career in Scots Law Faqs Final 09 Aberdeen Version

A Career in the Legal Profession in Scotland - Frequently Asked Questions This information sheet covers some of the key questions about a career in the legal profession in Scotland. It is particularly targeted at Scots law students and people considering studying the graduate entry 2 year accelerated LLB in Scotland. Following a major review of legal education and training in Scotland by the Law Society of Scotland, it is anticipated that a new route to qualification will be in place for academic year 2011/2012. The information in this leaflet refers to the situation at the time of writing (July 09) This FAQ sheet is a starting point. Additional information and resources can be found in our law folders at the Careers Service, 2 nd floor, The Hub, or in our online virtual library at www.abdn.ac.uk/careers . Initial Legal Training Page 1 Graduate entry LLB (2 year accelerated course) Page 1 Diploma in Legal Practice (DLP) Page 2 Becoming a Solicitor Page 4 Becoming an Advocate Page 6 General Law careers questions Page 7 Initial Legal Training The current route to qualification as a solicitor (and for intending advocates), is set out below • LLB degree (NB non-law graduates complete the 2 year accelerated law degree) • 26 week Diploma in Legal Practice • 2 year traineeship with solicitors’ firm or other organisation employing solicitors. (NB – same route for both solicitors and intending advocates to this point) • Bar Exams and a period of unpaid devilling for intending advocates. Following a major review of legal education and training in Scotland by the Law Society of Scotland, the following changes are in the process of being implemented, and it is anticipated that a new route to qualification will be in place for academic year 2011/2012. -

Daniel Kelly QC

Daniel Kelly QC Personal information Address Advocates’ Library, Parliament House, Edinburgh, EH1 1RF Telephone (work) 0131 226 5071 E-mail [email protected] Clerking information Clerk Susan Hastie Address Hastie Stable, Parliament House, Edinburgh, EH1 1RF Telephone 0131 260 5654 E-mail [email protected] Qualifications 1979 LLB (Hons), University of Edinburgh 1982 Certificat de Hautes Etudes Européenes, College of Europe, Bruges, Belgium Appointments 19 December 1997 – 1999 Temporary Sheriff 13 July 2005 to date Part-time Sheriff 2007 Queen’s Counsel Areas of interest Family Law Reparation Work experience 1979-1981 Apprentice, Dundas & Wilson, CS, Edinburgh 1982-1983 Solicitor, Brodies WS, Edinburgh Tutor, University of Edinburgh, European Institutions 1983-1984 Solicitor, Community Law Office, Brussels 1984 –1990 Procurator Fiscal Depute 1986 -1988 Seconded to Scottish Law Commission 1988 -1989 Seconded to Piper Alpha Enquiry Publications Books: Criminal Sentences , T & T Clark, Edinburgh, 1993. Greens Litigation Styles , Contributor, 1994. Butterworths Scottish Family Law Service , 2010, Contributing Editor. Bulletins: Criminal Law Bulletin , 1992 – 1997, Contributing Editor – Responsible for Recent Cases and latterly for Sentencing. Law Reports: Scots Law Times (Sheriff Court) Reports , Editor and then Consultant Editor, 1992 to date. Articles: The Sunday Times and Harman Cases: Freedom of expression, contempt of court and the European Convention on Human Rights , 1982 Journal of the Law Society of Scotland 408. From Bruocsella to Brussels , 1984 Journal of the Law Society of Scotland 139. The Brussels Enigma , 1984 New Law Journal 627. Jury Trial , 1988 SLT (News) 59. Codifying Criminal Law , 1988 SLT (News) 97. Aiding and Abetting , 1988 SLT (News) 201. -

Downloaded from Elgar Online at 09/26/2021 06:03:59PM Via Free Access

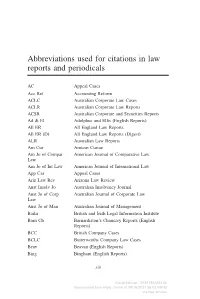

JOBNAME: Milman PAGE: 13 SESS: 8 OUTPUT: Fri Sep 28 09:22:10 2018 Abbreviations used for citations in law reports and periodicals AC Appeal Cases Acc Ref Accounting Reform ACLC Australian Corporate Law Cases ACLR Australian Corporate Law Reports ACSR Australian Corporate and Securities Reports Ad & El Adolphus and Ellis (English Reports) All ER All England Law Reports All ER (D) All England Law Reports (Digest) ALR Australian Law Reports Am Cur Amicus Curiae Am Jo of Compar American Journal of Comparative Law Law Am Jo of Int Law American Journal of International Law App Cas Appeal Cases Ariz Law Rev Arizona Law Review Aust Insolv Jo Australian Insolvency Journal Aust Jo of Corp Australian Journal of Corporate Law Law Aust Jo of Man Australian Journal of Management Bailii British and Irish Legal Information Institute Barn Ch Barnardiston’s Chancery Reports (English Reports) BCC British Company Cases BCLC Butterworths Company Law Cases Beav Beavan (English Reports) Bing Bingham (English Reports) xiii David Milman - 9781785368134 Downloaded from Elgar Online at 09/26/2021 06:03:59PM via free access Columns Design XML Ltd / Job: Milman-The_company_share / Division: Prelims /Pg. Position: 1 / Date: 20/9 JOBNAME: Milman PAGE: 14 SESS: 5 OUTPUT: Fri Sep 28 09:22:10 2018 xiv The company share BJIBFL Butterworths Journal of International Banking and Financial Law Bond Law Rev Bond Law Review BPIR Bankruptcy and Personal Insolvency Reports Camp Campbell (English Reports) Can Bus L Jo Canadian Business Law Journal Cap Mark Law Jo Capital Markets -

Law and Change Scottish Legal Heroes Pdf File 17

Law and society: Scottish legal heroes About this free course This version of the content may include video, images and interactive content that may not be optimised for your device. You can experience this free course as it was originally designed on OpenLearn, the home of free learning from The Open University – There you’ll also be able to track your progress via your activity record, which you can use to demonstrate your learning. Copyright © 2017 The Open University Intellectual property Unless otherwise stated, this resource is released under the terms of the Creative Commons Licence v4.0 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/deed.en_GB. Within that The Open University interprets this licence in the following way: www.open.edu/openlearn/about-openlearn/frequently-asked-questions-on-openlearn. Copyright and rights falling outside the terms of the Creative Commons Licence are retained or controlled by The Open University. Please read the full text before using any of the content. We believe the primary barrier to accessing high-quality educational experiences is cost, which is why we aim to publish as much free content as possible under an open licence. If it proves difficult to release content under our preferred Creative Commons licence (e.g. because we can’t afford or gain the clearances or find suitable alternatives), we will still release the materials for free under a personal end- user licence. This is because the learning experience will always be the same high quality offering and that should always be seen as positive – even if at times the licensing is different to Creative Commons. -

ALAN RODGER Alan Ferguson Rodger 1944–2011

ALAN RODGER Alan Ferguson Rodger 1944–2011 LORD RODGER OF EARLSFERRY, Justice of the United Kingdom Supreme Court, died from the effects of a brain tumour on 26 June 2011 at the age of 66. He was not only a lawyer and public servant of the highest distinc- tion but also a scholar with an academic publications record in Roman Law in particular that earned him election as a Fellow of the British Academy in 1991.1 The bare facts of his glitteringly varied career can be simply told. Brought up and educated in Glasgow before taking a D.Phil. in Roman Law at Oxford under the supervision of Professor David Daube, in 1974 he was called to the Scottish Bar, becoming as soon as 1976 Clerk of the Faculty of Advocates. He was appointed QC and an Advocate Depute in 1985, and then became a Scottish Law Officer under the Conservative Government, first as Solicitor General for Scotland in 1989 and next as Lord Advocate in 1992. He was appointed to the Scottish Bench in 1995 and in 1996 succeeded Lord Hope of Craighead as Lord President of the Court of Session and Lord Justice General in the High Court of Justiciary. In 2001 he joined Lord Hope as one of the two Scottish judges in the House of Lords; and when that court was trans- formed into the UK Supreme Court in October 2009 the two became the 1 He was also elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1992, and a Corresponding Fellow of the Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften in 2001.