Gustav Holst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Premiere of Angels' Atlas by Crystal Pite

World Premiere of Angels’ Atlas by Crystal Pite Presented with Chroma & Marguerite and Armand Principal Dancer Greta Hodgkinson’s Farewell Performances Casting Announced February 26, 2020… Karen Kain, Artistic Director of The National Ballet of Canada, today announced the casting for Angels’ Atlas by Crystal Pite which makes its world premiere on a programme with Chroma by Wayne McGregor and Marguerite and Armand by Frederick Ashton. The programme is onstage February 29 – March 7, 2020 at the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts. #AngelsAtlasNBC #ChromaNBC #MargueriteandArmandNBC The opening night cast of Angels’ Atlas features Principal Dancers Heather Ogden and Harrison James, First Soloist Jordana Daumec, Hannah Fischer and Donald Thom, Second Soloists Spencer Hack and Siphesihle November and Corps de Ballet member Hannah Galway. Principal Dancer Greta Hodgkinson retires from the stage after a career that has spanned over a period of 30 years. She will dance the role of Marguerite opposite Principal Dancer Guillaume Côté in Marguerite and Armand on opening night. The company will honour Ms. Hodgkinson at her final performance on Saturday, March 7 at 7:30 pm. Principal Dancers Sonia Rodriguez, Francesco Gabriele Frola and Harrison James will dance the title roles in subsequent performances. Chroma will feature an ensemble cast including Principal Dancers Skylar Campbell, Svetlana Lunkina, Heather Ogden and Brendan Saye, First Soloists Tina Pereira and Tanya Howard, Second Soloists Christopher Gerty, Siphesihle November and Brent -

Gp 3.Qxt 7/11/16 9:01 AM Page 1

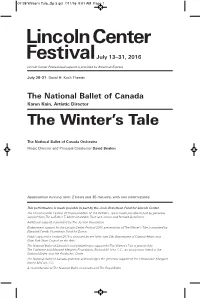

07-28 Winter's Tale_Gp 3.qxt 7/11/16 9:01 AM Page 1 July 13 –31, 2 016 Lincoln Center Festival lead support is provided by American Express July 28–31 David H. Koch Theater The National Ballet of Canada Karen Kain, Artistic Director The Winter’s Tale The National Ballet of Canada Orchestra Music Director and Principal Conductor David Briskin Approximate running time: 2 hours and 35 minutes, with two intermissions This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. The Lincoln Center Festival 2016 presentation of The Winter’s Tale is made possible in part by generous support from The LuEsther T. Mertz Charitable Trust and Jennie and Richard DeScherer. Additional support is provided by The Joelson Foundation. Endowment support for the Lincoln Center Festival 2016 presentation of The Winter’s Tale is provided by Blavatnik Family Foundation Fund for Dance. Public support for Festival 2016 is provided by the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs and New York State Council on the Arts. The National Ballet of Canada’s lead philanthropic support for The Winter’s Tale is provided by The Catherine and Maxwell Meighen Foundation, Richard M. Ivey, C.C., an anonymous friend of the National Ballet, and The Producers’ Circle. The National Ballet of Canada gratefully acknowledges the generous support of The Honourable Margaret Norrie McCain, C.C. A co-production of The National Ballet of Canada and The Royal Ballet 07-28 Winter's Tale_Gp 3.qxt 7/11/16 9:01 AM Page 2 LINCOLN CENTER FESTIVAL 2016 THE WINTER’S -

Love and Ballet at Pacific Northwest Ballet Encore Arts Seattle

June 2018 June 2018 Volume 31, No. 7 Paul Heppner Publisher Susan Peterson Design & Production Director Ana Alvira, Robin Kessler, Stevie VanBronkhorst Production Artists and Graphic Design Mike Hathaway Sales Director Brieanna Bright, Joey Chapman, Ann Manning Seattle Area Account Executives Amelia Heppner, Marilyn Kallins, Terri Reed San Francisco/Bay Area Account Executives Carol Yip Sales Coordinator Leah Baltus Editor-in-Chief Andy Fife Publisher Dan Paulus Art Director Gemma Wilson, Jonathan Zwickel Senior Editors Amanda Manitach Visual Arts Editor Paul Heppner President Mike Hathaway Vice President Kajsa Puckett Vice President, Marketing & Business Development Genay Genereux Accounting & Office Manager Shaun Swick Senior Designer & Digital Lead Barry Johnson Digital Engagement Specialist Ciara Caya Customer Service Representative & Administrative Assistant Corporate Office 425 North 85th Street Seattle, WA 98103 p 206.443.0445 f 206.443.1246 [email protected] 800.308.2898 x105 www.encoremediagroup.com Encore Arts Programs is published monthly by Encore Media Group to serve musical and theatrical events in the Puget Sound and San Francisco Bay Areas. All rights reserved. ©2018 Encore Media Group. Reproduction without written permission is prohibited. 2 PACIFIC NORTHWEST BALLET PACIFIC NORTHWEST BALLET Kent Stowell and Peter Boal June 1–10, 2018 Francia Russell Artistic Director Marion Oliver McCaw Hall Founding Artistic Directors PRINCIPALS Karel Cruz Lindsi Dec Rachel Foster Benjamin Griffiths William Lin-Yee James Moore -

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater Launches 23-City North American Tour with Nearly 90 Performances: February 4 – May 11

ALVIN AILEY AMERICAN DANCE THEATER LAUNCHES 23-CITY NORTH AMERICAN TOUR WITH NEARLY 90 PERFORMANCES: FEBRUARY 4 – MAY 11 Tour Repertory Features 2013-14 Season Premieres and New Productions from a Wide Range of Choreographic Voices as Artistic Director Robert Battle Continues to Expand Diverse Repertory and Gives Ailey’s Extraordinary Dancers New Ways to Inspire Season World Premieres LIFT by In-Demand Choreographer Aszure Barton and Four Corners by Celebrated Dance Maker Ronald K. Brown Company Premiere of Chroma Marks First Time a Work by the Multi Award-Winning British Choreographer Wayne McGregor Appears in Repertory and Modern Dance Innovator Bill T. Jones’ Joyful Tour-De-Force D-Man in the Waters (Part I) Celebrates the Resilience of the Human Spirit 25th Season Since the Passing of Legendary Founder Features Ailey/Ellington Program with New Productions of Alvin Ailey’s The River and Pas de Duke Set to Duke Ellington’s Music Announcement of 2014 15-Performance Engagement at Lincoln Center’s David H. Koch Theater June 11 – 22 NEW YORK – February 4, 2014 — Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, beloved as one of the world’s most popular dance companies, will travel coast to coast on a 23-city North American tour with almost 90 performances from February 4th through May 11th, following a record-breaking season launch at New York City Center where Ailey is the Principal Dance Company and its performances are a year-end tradition. In addition, today Artistic Director Robert Battle announced that the Company would return to Lincoln Center’s David H. Koch Theater from June 11th to 22nd for a 15-performance engagement. -

Program Notes

YELLOW EARTH PROGRAM NOTES Quanta was commissioned by China’s Quanta (2012) Blow It Up, Start Again National Centre for the Performing Arts for the Sebastian Currier (b. 1959) “Composing China” project. It was premiered (2011) [United States Premiere] on March 17, 2013, in Beijing with the National Jonathan Newman (b. 1972) Centre for the Performing Arts Orchestra, When I first came to China with a group of my conducted by Kristjan Jarvi. If the system isn’t working anymore, then do colleagues, I was often asked, “how is China what Guy Fawkes tried and go anarchist: blow it Not recorded different from the United States?” Implicit in all up, and start again. the question is that it is indeed very different, —Jonathan Newman and of course in many ways it is. But touching The Color Yellow: down in Beijing from New York, one cannot help Concerto for Sheng (2007) Blow It Up, Start Again was commissioned but note the many similarities. Sure, when one by the Chicago Youth Symphony Orchestras visits the treasures of the past, the Forbidden Huang Ruo (b. 1976) and premiered on May 13, 2012, at Chicago City, the Temple of Heaven, one encounters [West Coast Premiere] Symphony Center, conducted by Allen Tinkham. difference. But that is to travel far back in time. The more modern the context the more similar Sheng, the Chinese mouth organ and a Not recorded we seem. The grid structure, the materials used thousand-year-old traditional instrument, is for roads, the design of traffic lights, the more often referred to as the ancestor of the Western Chroma (2007) modern architectural structures—all have close organ. -

Pilgrimage and Postminimalism in Joby Talbot's Path Of

PILGRIMAGE AND POSTMINIMALISM IN JOBY TALBOT’S PATH OF MIRACLES by JOY ELIZABETH MEADE Under the Direction of DANIEL BARA ABSTRACT Joby Talbot’s Path of Miracles is a seventy-minute a cappella choral masterwork that portrays the experience of a pilgrim traveling the Camino de Santiago. Composed in 2005 on commission from Nigel Short for his professional choir Tenebrae, Path of Miracles is a modern- day soundtrack of this enduring pilgrimage. This paper examines Path of Miracles from three perspectives: as a representation of pilgrimage, as a reflection of the sacred and secular aspects of the Camino de Santiago, and as an example of a postminimalism in a choral work. Chapter 2 studies Path of Miracles as a musical depiction of common pilgrimage experiences as explained by anthropologists. Modern pilgrimage scholarship examines a person’s motivation to take a pilgrimage, his or her separation from daily life and social status, the re-shaping of a pilgrim’s identity along the journey, the physical effect of constant walking on the mind and body, and the re-entrance of the pilgrim into society. Path of Miracles represents these stages of pilgrimage musically. Additionally, Chapter 2 demonstrates how Path of Miracles is a modern-day, musical depiction of the French route, and this chapter will explore how the piece serves as a musical guidebook, depicting the landscape, cathedrals, cultures, people and sounds found on the Camino Frances. Chapter 3 examines the sacred and secular musical elements found in Path of Miracles, and how these elements portray the dichotomy of religious and non-religious aspects of the Camino’s history. -

Winters Tale Ballet Notes 2015

10 Celebrating 10 Years as Artistic Director 2015 /16 Season presents The Winter’s Tale North American Premiere! November 14—22 national.ballet.ca Hannah Fischer and Piotr Stanczyk. Photo by Karolina Kuras. Hannah Fischer is sponsored through Dancers First by Judy & Bella Matthews. 2015 /16 season Fall Season The Winter’s Tale Romeo and Juliet Holiday Season The Nutcracker Celia Franca, C.C., Founder Winter Season La Sylphide George Crum, Music Director Emeritus Cacti & Rubies & The Four Temperaments Karen Kain, C.C. Barry Hughson Romeo and Juliet Artistic Director Executive Director Summer Season David Briskin Rex Harrington,O.C. Music Director and Artist-in-Residence Le Petit Prince Principal Conductor Giselle Magdalena Popa Lindsay Fischer Principal Artistic Artistic Director, Coach YOU dance / Principal Ballet Master Peter Ottmann Mandy-Jayne Richardson Senior Ballet Master Senior Ballet Mistress Guillaume Côté, Jurgita Dronina, Naoya Ebe, Greta Hodgkinson, Elena Lobsanova, Svetlana Lunkina, McGee Maddox, Evan McKie, Heather Ogden, Sonia Rodriguez, Piotr Stanczyk, Jillian Vanstone, Xiao Nan Yu Lorna Geddes, Stephanie Hutchison, Etienne Lavigne, Alejandra Perez-Gomez, Jonathan Renna, Rebekah Rimsay, Tomas Schramek, Hazaros Surmeyan Skylar Campbell, Jordana Daumec, Francesco Gabriele Frola, Tanya Howard, Harrison James, Chelsy Meiss, Tina Pereira, Jenna Savella, Robert Stephen, Dylan Tedaldi Jack Bertinshaw, Hannah Fischer, Emma Hawes, Kathryn Hosier, Alexandra MacDonald, Tiffany Mosher*, Brent Parolin, Brendan Saye Trygve Cumpston, -

Signumclassics

078booklet 13/10/08 11:27 Page 1 ALSO on signumclassics Mother and Child SIGCD501 Dream of Herod SIGCD046 A distinctive and distinguished collection of works by a This disc features music for A d v e n t , anthems for the Mother number of living composers, including five world première and Child, music for Christmas, and T h e Dream of Herod, r e c o r d i n g s . The centre-piece of the disc is a new commission a semi-dramatic contemporary work with a particular for Tenebrae from the world acclaimed composer Sir John resonance at Christmas. C o m p o s e r s : S h o r t , W i s h a r t , Tavener (Mother and Child). Other composers are: Dove, Howells, Hadley, Chilcott, Gruber, and Kirkpatrick; as Pott, Swayne, L’Estrange, Filsell and Rodney Bennett. well as traditional Christmas music. www.signumrecords.com www.jobytalbot.com www.tenebrae-choir.com Available through most record stores and at www.signumrecords.com For more information call +44 (0) 20 8997 4000 078booklet 13/10/08 11:27 Page 3 The musical traditions of the Pilgrimage can be traced to The ‘Camino Frances’ is the central axis of a network of Path of miracles the mid-12th Century, when a compilation of texts pilgrimage routes to Santiago. Its travellers gather in joby talbot attributed to Pope Calixtus II was created, all devoted to Roncesvalles, a small town at the foot of the Pyrenees the cult of St James. This so-called ‘Codex Calixtinus’ was which in the spring becomes a veritable Babel as specifically designed to serve the needs of worshippers pilgrims from across the world assemble, before setting and pilgrims in Santiago, and consisted of five books. -

Joby Talbot Paper

Joby Talbot: An Analysis of Path of Miracles and Ave Verum Corpus Richard Carrick MUSIC 484: Choral Repertoire of the 20th-Century Dr. Giselle Wyers March 19, 2019 Carrick 1 Joby Talbot’s composition portfolio is quite impressive and well diversified. Born in London in 1971, Talbot began his musical studies as a young child playing piano and oboe, and performed his first composition at age 9.1 Talbot then went on to study music and composition at Royal Holloway and Bedford New College and then earned his Master of Music in composition at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, where he studied with Simon Bainbridge.2 Following his studies at Royal Holloway, Joby Talbot toured with a rock band, The Divine Comedy, for nearly a decade. This choice in career path is more unconventional than other composers in the classical music genre. Talbot’s role with the band was to create arrangements, serve as Music Director, and conduct the orchestra that would accompany the band. While touring with The Divine Comedy, Talbot simultaneously composed music, receiving commissions from the Kings’ Singers, the BBC Philharmonic, Paul McCartney, and film- studios.3 Joby Talbot’s film credits includes the music to several major motion pictures. Two of the movies he scored with the highest grossing box office are, Sing! and The Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy. Talbot also composed the theme music and television and film scores to the popular British Series, The League of Gentlemen.4 In addition to film scores, Talbot has composed many Ballets, and recently premiered his opera, Everest, with Dallas Opera. -

Kevin O'hare Director of the Royal Ballet

Kevin O’Hare Director of The Royal Ballet Approved, OK to use Kevin O’Hare was born in Yorkshire. Having started dancing at an early age, he trained at The Royal Ballet School from the age of 11 and, through an exchange programme, Royal Danish Ballet. On graduating he joined Sadler’s Wells Royal Ballet under the direction of Peter Wright and was promoted to Principal in 1990 at the same time as the company relocated to Birmingham, becoming Birmingham Royal Ballet. Performing across the UK and worldwide, he danced all the leading classical roles including Siegfried, Florimund, Albrecht and Romeo (in the first performance of Kenneth MacMillan’s new production of Romeo and Juliet for BRB), and created the role of Amynta in David Bintley’s full-length Sylvia. He also danced in major works by Ashton, Balanchine, Cranko, MacMillan, Van Manen, Tharp and Tudor. During his performing career he worked with Ashton, De Valois, MacMillan, Bintley and Wright, among others, as well as creating many roles. He has made guest appearances with companies all over the world, and produced many galas and choreographic evenings. He retired from dancing in 2000 to work with the RSC, training in company management. He returned to BRB as Company Manager in 2001 and joined The Royal Ballet as Company Manager in 2004. He was appointed Administrative Director in 2009 and Director in July 2012. Since then, in addition to presenting the Company’s heritage repertory, he has demonstrated his commitment to new work by commissioning many one-act and five full-length ballets. -

Edition 2 | 2019-2020

WHAT’S INSIDE Welcome From the Board Chair ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 7 From the General Director & CEO ������������������������������������������������������������������� 9 Everest Sponsors ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 5 A Note from Librettist Gene Scheer ��������������������������������������������������������������� 11 Directors Note ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 13 Staff ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 15 Board ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 17 Beyond the Opera House �������������������������������������������������������������������������������20 A Tribute to Steven Barbaro ���������������������������������������������������������������������������� 21 Title Page ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������23 Production Page �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������25 Synopsis ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������27 Cast �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������28 Creative Team �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� -

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland Fool's Paradise

ALICE’S ADVENTURES IN WONDERLAND An Alice without words FOOL’S PARADISE “[Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland] is a book JOBY TALBOT of that extremely rare kind, which will belong to all the generations to come until the language becomes obsolete.” Sir Walter Besant, 1897 Suite from Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland 1 Prologue [6.48] Joby Talbot’s ballet scores for Alice’s Adventures 2 The Mad Hatter’s Tea-Party [3.08] in Wonderland and Fool’s Paradise were 3 Alice Alone [4.18] both created in collaboration with celebrated 4 The Croquet Match [5.33] choreographer Christopher Wheeldon, who first approached Talbot after hearing his piano trio 5 Setting Up the Courtroom [2.46] The Dying Swan. This latter work was originally 6 The Queen of Hearts’ Tango [2.09] commissioned by the British Film Institute in 7 The Cheshire Cat [2.56] 2002 as a new score for the 1917 silent film of 8 The Flower Garden Part I [7.00] the same name by Russian director Evgenii 9 The Flower Garden Part II [4.44] Bauer, itself illustrating the assorted trials of Fool’s Paradise a delicate ballerina in monochrome peril. The 0 Part I [4.58] score’s yearning propulsion and exquisite q Part II [10.40] dissonances evidently suggested to Wheeldon a greater kinetic potential, and so The Dying w Part III [6.51] Swan for piano trio blossomed into Fool’s e Part IV [5.19] Paradise for string orchestra and a new life in Total timings: [67.12] ballet, premiering with New York-based dance company Morphoses at Sadler’s Wells Theatre in London in September 2007.