CENTAUROMACHY: the South Metopes of the Parthenon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MYTHOLOGY MAY 2018 Detail of Copy After Arpino's Perseus and Andromeda

HOMESCHOOL THIRD THURSDAYS MYTHOLOGY MAY 2018 Detail of Copy after Arpino's Perseus and Andromeda Workshop of Giuseppe Cesari (Italian), 1602-03. Oil on canvas. Bequest of John Ringling, 1936. Creature Creation Today, we challenge you to create your own mythological creature out of Crayola’s Model Magic! Open your packet of Model Magic and begin creating. If you need inspiration, take a look at the back of this sheet. MYTHOLOGICAL Try to incorporate basic features of animals – eyes, mouths, legs, etc.- while also combining part of CREATURES different creatures. Some works of art that we are featuring for Once you’ve finished sculpting, today’s Homeschool Third Thursday include come up with a unique name for creatures like the sea monster. Many of these your creature. Does your creature mythological creatures consist of various human have any special powers or and animal parts combined into a single creature- abilities? for example, a centaur has the body of a horse and the torso of a man. Other times the creatures come entirely from the imagination, like the sea monster shown above. Some of these creatures also have supernatural powers, some good and some evil. Mythological Creatures: Continued Greco-Roman mythology features many types of mythological creatures. Here are some ideas to get your project started! Sphinxes are wise, riddle- loving creatures with bodies of lions and heads of women. Greek hero Perseus rides a flying horse named Pegasus. Sphinx Centaurs are Greco- Pegasus Roman mythological creatures with torsos of men and legs of horses. Satyrs are creatures with the torsos of men and the legs of goats. -

Parthenon 1 Parthenon

Parthenon 1 Parthenon Parthenon Παρθενών (Greek) The Parthenon Location within Greece Athens central General information Type Greek Temple Architectural style Classical Location Athens, Greece Coordinates 37°58′12.9″N 23°43′20.89″E Current tenants Museum [1] [2] Construction started 447 BC [1] [2] Completed 432 BC Height 13.72 m (45.0 ft) Technical details Size 69.5 by 30.9 m (228 by 101 ft) Other dimensions Cella: 29.8 by 19.2 m (98 by 63 ft) Design and construction Owner Greek government Architect Iktinos, Kallikrates Other designers Phidias (sculptor) The Parthenon (Ancient Greek: Παρθενών) is a temple on the Athenian Acropolis, Greece, dedicated to the Greek goddess Athena, whom the people of Athens considered their patron. Its construction began in 447 BC and was completed in 438 BC, although decorations of the Parthenon continued until 432 BC. It is the most important surviving building of Classical Greece, generally considered to be the culmination of the development of the Doric order. Its decorative sculptures are considered some of the high points of Greek art. The Parthenon is regarded as an Parthenon 2 enduring symbol of Ancient Greece and of Athenian democracy and one of the world's greatest cultural monuments. The Greek Ministry of Culture is currently carrying out a program of selective restoration and reconstruction to ensure the stability of the partially ruined structure.[3] The Parthenon itself replaced an older temple of Athena, which historians call the Pre-Parthenon or Older Parthenon, that was destroyed in the Persian invasion of 480 BC. Like most Greek temples, the Parthenon was used as a treasury. -

A Collection of Curricula for the STARLAB Greek Mythology Cylinder

A Collection of Curricula for the STARLAB Greek Mythology Cylinder Including: A Look at the Greek Mythology Cylinder Three Activities: Constellation Creations, Create a Myth, I'm Getting Dizzy by Gary D. Kratzer ©2008 by Science First/STARLAB, 95 Botsford Place, Buffalo, NY 14216. www.starlab.com. All rights reserved. Curriculum Guide Contents A Look at the Greek Mythology Cylinder ...................3 Leo, the Lion .....................................................9 Introduction ......................................................3 Lepus, the Hare .................................................9 Andromeda ......................................................3 Libra, the Scales ................................................9 Aquarius ..........................................................3 Lyra, the Lyre ...................................................10 Aquila, the Eagle ..............................................3 Ophuichus, Serpent Holder ..............................10 Aries, the Ram ..................................................3 Orion, the Hunter ............................................10 Auriga .............................................................4 Pegasus, the Winged Horse..............................11 Bootes ..............................................................4 Perseus, the Champion .....................................11 Cancer, the Crab ..............................................4 Phoenix ..........................................................11 Canis Major, the Big Dog -

AND DID THOSE HOOVES Pan and the Edwardians

1 AND DID THOSE HOOVES Pan and the Edwardians By Eleanor Toland A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Literature Victoria University of Wellington 2014 2 “….a goat’s call trembled from nowhere to nowhere…” James Stephens, The Crock of Gold, 1912 3 Contents Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………...4 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………………………………..5 Introduction: Pan and the Edwardians………………………………………………………….6 Chapter One: Pan as a Christ Figure, Christ as a Pan Figure…………………………………...17 Chapter Two: Uneasy Dreams…………………………………………..…………………......28 Chapter Three: Savage Wildness to Garden God………….…………………………………...38 Chapter Four: Culminations….................................................................................................................48 Chapter Five: The Prayer of the Flowers………………...…………………………………… 59 Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………….70 Works Cited…………………………………………………………………………………...73 4 Acknowledgements My thanks to Lilja, Lujan, Saskia, Thomas, Emily, Eve, Mehdy, Eden, Margie, Katie, Anna P, the other Anna P, Hannah, Sarah, Caoilinn, Ronan, Kay, Angelina, Iain et Alana and anyone else from the eighth and ninth floor of the von Zedlitz building who has supplied a friendly face or a kind word. Your friendship and encouragement has been a fairy light leading me out of a perilous swamp. Thank you to my supervisors, Charles and Geoff, without whose infinite patience and mentorship this thesis would never have been finished, and whose supervision went far beyond the call of duty. Finally, thank you to my family for their constant support and encouragement. 5 Abstract A surprisingly high number of the novels, short stories and plays produced in Britain during the Edwardian era (defined in the terms of this thesis as the period of time between 1900 and the beginning of World War One) use the Grecian deity Pan, god of shepherds, as a literary motif. -

Highlights from the Plaster Cast Collection

Fairfield University DigitalCommons@Fairfield Gifts from Athens - Ephemera Gifts From Athens 9-2010 Highlights from the Plaster Cast Collection Katherine Schwab Fairfield University, [email protected] Jill J. Deupi Fairfield University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/gifts-from-athens-ephemera Recommended Citation Schwab, Katherine and Deupi, Jill J., "Highlights from the Plaster Cast Collection" (2010). Gifts from Athens - Ephemera. 1. https://digitalcommons.fairfield.edu/gifts-from-athens-ephemera/1 This item has been accepted for inclusion in DigitalCommons@Fairfield by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Fairfield. It is brought to you by DigitalCommons@Fairfield with permission from the rights- holder(s) and is protected by copyright and/or related rights. You are free to use this item in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses, you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Highlights from the Plaster Cast Collection 1 Plaster Casts Technical Notes Plaster casts are replicas of other works of art. While the methods used to create casts vary, most commonly a mould is created by applying plaster of Paris, gelatin, silicone rubber or polyurethane to the original artifact. After the mould dries, it is removed, retaining an impression of the source object on its interior surfaces. Wet plaster is then poured into the resulting cavity. When this is dry, the mould is removed and the new cast is revealed. -

Centaur Mind: a Glimpse Into an Integrative Structure of Consciousness

Journal of Conscious Evolution Volume 16 Issue 1 Articles from an Art and Consciousness Article 4 Class 11-7-2020 Centaur Mind: A Glimpse into an Integrative Structure of Consciousness Azin Izadifar California Institute of Integral Studies Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/cejournal Part of the Clinical Psychology Commons, Cognition and Perception Commons, Cognitive Psychology Commons, Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, Liberal Studies Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, Social and Philosophical Foundations of Education Commons, Social Psychology Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, Sociology of Religion Commons, and the Transpersonal Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Izadifar, Azin (2020) "Centaur Mind: A Glimpse into an Integrative Structure of Consciousness," Journal of Conscious Evolution: Vol. 16 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.ciis.edu/cejournal/vol16/iss1/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals and Newsletters at Digital Commons @ CIIS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Conscious Evolution by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ CIIS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Izadifar: Centaur Mind: A Glimpse into an Integrative Structure of Journal of Conscious Evolution| Fall 2020 | Vol. 16 (1) | Azin Izadifar – Centaur Mind: A Glimpses into an Integrative Structure of Consciousness Centaur Mind: A Glimpse into an Integrative Structure of Consciousness Dr. Azin Izadifar www.Azinizadifar.com Abstract: Jean Gebser’s theory of consciousness suggests that we are experiencing a new era in the history of consciousness. -

N AS a Facts

National Aeronautics and Space Administration NASA’s Launch Services Program he Launch Services Program (LSP) manufacturing, launch operations and rockets for launching Earth-orbit and Twas established at Kennedy Space countdown management, and providing interplanetary missions. Center for NASA’s acquisition and added quality and mission assurance in In September 2010, NASA’s Launch program management of expendable lieu of the requirement for the launch Services (NLS) contract was extended launch vehicle (ELV) missions. A skillful service provider to obtain a commercial by the agency for 10 years, through NASA/contractor team is in place to launch license. 2020, with the award of four indefinite meet the mission of the Launch Ser- Primary launch sites are Cape Canav- delivery/indefinite quantity contracts. The vices Program, which exists to provide eral Air Force Station (CCAFS) in Florida, expendable launch vehicles that NASA leadership, expertise and cost-effective and Vandenberg Air Force Base (VAFB) has available for its science, Earth-orbit services in the commercial arena to in California. and interplanetary missions are United satisfy agencywide space transporta- Other launch locations are NASA’s Launch Alliance’s (ULA) Atlas V and tion requirements and maximize the Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia, the Delta II, Space X’s Falcon 1 and 9, opportunity for mission success. Kwajalein Atoll in the South Pacific’s Orbital Sciences Corp.’s Pegasus and facts The principal objectives of the LSP Republic of the Marshall Islands, and Taurus XL, and Lockheed Martin Space are to provide safe, reliable, cost-effec- Kodiak Island in Alaska. Systems Co.’s Athena I and II. -

Hybrid Monsters

HYBRID MONSTERS IN THE CLASSICAL WORLD THE NATURE AND FUNCTION OF HYBRID MONSTERS IN GREEK MYTHOLOGY, LITERATURE AND ART by Liane Posthumus Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Master of Philosophy in Ancient Cultures at the University of Stellenbosch Supervisor: Prof. J.C. Thom Co-supervisor: Dr. S. Thom Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Department of Ancient Studies March 2011 Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the authorship owner thereof (unless to the extent explicitly otherwise stated) and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. Date: 28 February 2011 Copyright © 2010 University of Stellenbosch All rights reserved i ABSTRACT The aim of this thesis is to explore the purpose of monster figures by investigating the relationship between these creatures and the cultures in which they are generated. It focuses specifically on the human-animal hybrid monsters in the mythology, literature and art of ancient Greece. It attempts to answer the question of the purpose of these monsters by looking specifically at the nature of man- horse monsters and the ways in which their dichotomous internal and external composition challenged the cultural taxonomy of ancient Greece. It also looks at the function of monsters in a ritual context and how the Theseus myth, as initiation myth, and the Minotaur, as hybrid monster, conforms to the expectations of ritual monsters. The investigation starts by considering the history and uses of the term “monster” in an attempt to arrive at a reasonable definition of monstrosity. -

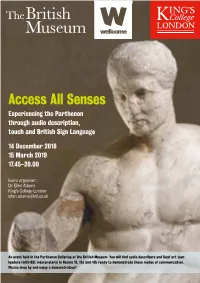

Access All Senses Experiencing the Parthenon Through Audio Description, Touch and British Sign Language

Access All Senses Experiencing the Parthenon through audio description, touch and British Sign Language 14 December 2018 15 March 2019 17.45–20.00 Event organiser: Dr Ellen Adams King’s College London [email protected] An event held in the Parthenon Galleries of the British Museum. You will find audio describers and Deaf art tour leaders (with BSL interpreters) in Rooms 18, 18a and 18b ready to demonstrate these modes of communication. Please drop by and enjoy a demonstration!’ The Parthenon Galleries of the British Museum The Parthenon’s sculptural programme Drawn by Ellen Adams (Blue: frieze; Green: pediments; Red: metopes) The Parthenon was constructed in the fifth century BC on the Athenian Acropolis. One of the most impressive monuments from the ancient world, it possessed an Drawn by Ellen Adams elaborate and sophisticated sculptural programme, which celebrated Greek We may compare this layout with the original sculptural programme (see across). (or Athenian) greatness. page 2 page 3 What is Audio Description (AD)? What is British Sign Language (BSL)? AD provides access for blind or partially sighted (BPS) people, by using words to Sign languages are not simply manual versions of the local spoken language. create vivid visions and sensory experiences in the mind. Most BPS people can see BSL has a clear set of grammatical rules based on entirely different criteria from something – shapes, colours, or tunnel-vision. Spoken language can help make sense spoken English. There are estimated to be 50,000-70,000 people in the UK who state of this partial information. AD is a practice-led activity, and is studied and taught in BSL as their preferred language. -

1 the Curse of Minerva

1 The Curse of Minerva edited by Peter Cochran The Marbles would have gone in the vertically-lined section beneath the upper part. Built between 447 and 432 BC, the Parthenon symbolises, not Greek civilisation, so much as Athenian political hegemony over the rest of Greece (which the Athenians would have said was the same thing). It is a statement of imperialist triumph. The metopes around its border symbolise (or symbolised) the triumph of Athenian order over barbarian chaos: battles against the Amazons, between the Lapiths and the Centaurs, between the Gods and the Giants, and between the Greeks and the Trojans. Athens in Byron’s day In Byron’s time Athens was technically the fiefdom one of the Black Eunuchs at Constantinople, 1 and neither the town nor its archaeological treasures was much valued by either its Greek inhabitants or its Turkish rulers; though Byron does record in a note to Childe Harold II that as Lord Elgin’s servants lifted yet another marble from the building, a Turkish officer witnessing the depredation wept, and said “enough!”. This observation was made not by Byron, but by his friend Edward Daniel Clarke, and Byron put it into later editions. 2 By the time Lord Elgin and Byron arrived in Greece, the building was in an advanced state of decay. A major disaster had occurred in 1687, when the Venetian general Francesco Morosini besieged the place, and, knowing that the Turks had gunpowder stored in it, 1: See The Giaour , 151, Byron’s note. 2: See CHP II stanzas 11-14, and Byron’s prose notes, for more thoughts about the marbles. -

SPECIAL TOURS MYTHOLOGY Gallery of Greek and Roman Casts

SPECIAL TOURS MYTHOLOGY Gallery of Greek and Roman Casts Battle of the Greeks and Amazons Temple of Apollo at Phigaleia (Bassai) Greek, late 5th c. B.C. The Mausoleion at Halikarnassos Greek, ca. 360-340 B.C. Myth: The Amazons lived in the northern limits of the known world. They were warrior women who fought from horseback usually with bow and arrows, but also with axe and spear. Their shields were crescent shaped. They destroyed the right breast of young Amazons, to facilitate use of the bow. The Attic hero Theseus had joined Herakles on his expedition against them and received the Amazon Antiope (or Hippolyta) as his share of the spoils of war. In revenge, the Amazons invaded Attica. In the subsequent battle Antiope was killed. This battle was represented in a number of works, notably the metopes of the Parthenon and the shield of the Athena Parthenos, the great cult statue by Pheidias that stood in the Parthenon. Symbolically, the battle represents the triumph of civilization over barbarism. Battle of the Gods and Giants Altar of Zeus and Athena, Pergamon (Zeus battling Giants) Greek, ca. 180 B.C. Myth: The giants, born of Earth, threatened Zeus and the other gods, and a fierce struggle ensued, the so-called Gigantomachy, or battle of the gods and giants. The giants were defeated and imprisoned below the earth. This section of the frieze from the altar shows Zeus battling three giants. The myth may reflect an event of prehistory, the arrival ca. 2000 B.C. of Greek- speaking invaders, who brought with them their own gods, whose chief god was Zeus. -

The Case of the Parthenon Sculptures

University of North Florida UNF Digital Commons All Volumes (2001-2008) The sprO ey Journal of Ideas and Inquiry 2007 Looted Art: The aC se of the Parthenon Sculptures Alison Lindsey Moore University of North Florida Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unf.edu/ojii_volumes Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Suggested Citation Moore, Alison Lindsey, "Looted Art: The asC e of the Parthenon Sculptures" (2007). All Volumes (2001-2008). 34. http://digitalcommons.unf.edu/ojii_volumes/34 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the The sprO ey Journal of Ideas and Inquiry at UNF Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Volumes (2001-2008) by an authorized administrator of UNF Digital Commons. For more information, please contact Digital Projects. © 2007 All Rights Reserved LOOTED ART: Art returning to Italy a number of smuggled artifacts, including the famous THE CASE OF THE PARTHENON calyx-krater by Euphronios. The J. Paul SCULPTURES Getty Museum in California also recently attracted attention as Marion True, the Alison Lindsey Moore museum’s former curator of antiquities, was accused of knowingly purchasing Faculty Sponsor: Dr. Candice Carter, looted artifacts. Rather than focusing on a Associate Professor of Curriculum and recent case, I concentrate on the Instruction (Elementary Education) controversy surrounding the so-called “Elgin Marbles.” This research project was intended Many artifacts which comprise private to contextualize both the historical and and museum collections today were possibly current controversial issues pertaining to stolen from their country of origin and illegally the Parthenon. The first section titled “The smuggled into the country in which they now Architectural and Decorative Elements of reside.