Internationa L Sem Inar La Ngu Age Ma Intenan Ce and Shift II. July 5-6, 20 12 @ Su Pp Orted B Y M Aster Program in Ling U Istic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ka И @И Ka M Л @Л Ga Н @Н Ga M М @М Nga О @О Ca П

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N3319R L2/07-295R 2007-09-11 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Международная организация по стандартизации Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Proposal for encoding the Javanese script in the UCS Source: Michael Everson, SEI (Universal Scripts Project) Status: Individual Contribution Action: For consideration by JTC1/SC2/WG2 and UTC Replaces: N3292 Date: 2007-09-11 1. Introduction. The Javanese script, or aksara Jawa, is used for writing the Javanese language, the native language of one of the peoples of Java, known locally as basa Jawa. It is a descendent of the ancient Brahmi script of India, and so has many similarities with modern scripts of South Asia and Southeast Asia which are also members of that family. The Javanese script is also used for writing Sanskrit, Jawa Kuna (a kind of Sanskritized Javanese), and Kawi, as well as the Sundanese language, also spoken on the island of Java, and the Sasak language, spoken on the island of Lombok. Javanese script was in current use in Java until about 1945; in 1928 Bahasa Indonesia was made the national language of Indonesia and its influence eclipsed that of other languages and their scripts. Traditional Javanese texts are written on palm leaves; books of these bound together are called lontar, a word which derives from ron ‘leaf’ and tal ‘palm’. 2.1. Consonant letters. Consonants have an inherent -a vowel sound. Consonants combine with following consonants in the usual Brahmic fashion: the inherent vowel is “killed” by the PANGKON, and the follow- ing consonant is subjoined or postfixed, often with a change in shape: §£ ndha = § NA + @¿ PANGKON + £ DA-MAHAPRANA; üù n. -

Proposal for a Gurmukhi Script Root Zone Label Generation Ruleset (LGR)

Proposal for a Gurmukhi Script Root Zone Label Generation Ruleset (LGR) LGR Version: 3.0 Date: 2019-04-22 Document version: 2.7 Authors: Neo-Brahmi Generation Panel [NBGP] 1. General Information/ Overview/ Abstract This document lays down the Label Generation Ruleset for Gurmukhi script. Three main components of the Gurmukhi Script LGR i.e. Code point repertoire, Variants and Whole Label Evaluation Rules have been described in detail here. All these components have been incorporated in a machine-readable format in the accompanying XML file named "proposal-gurmukhi-lgr-22apr19-en.xml". In addition, a document named “gurmukhi-test-labels-22apr19-en.txt” has been provided. It provides a list of labels which can produce variants as laid down in Section 6 of this document and it also provides valid and invalid labels as per the Whole Label Evaluation laid down in Section 7. 2. Script for which the LGR is proposed ISO 15924 Code: Guru ISO 15924 Key N°: 310 ISO 15924 English Name: Gurmukhi Latin transliteration of native script name: gurmukhī Native name of the script: ਗੁਰਮੁਖੀ Maximal Starting Repertoire [MSR] version: 4 1 3. Background on Script and Principal Languages Using It 3.1. The Evolution of the Script Like most of the North Indian writing systems, the Gurmukhi script is a descendant of the Brahmi script. The Proto-Gurmukhi letters evolved through the Gupta script from 4th to 8th century, followed by the Sharda script from 8th century onwards and finally adapted their archaic form in the Devasesha stage of the later Sharda script, dated between the 10th and 14th centuries. -

The Local Wisdom in Javanese Thinking Culture Within Hanacaraka Philosophy

THE LOCAL WISDOM IN JAVANESE THINKING CULTURE WITHIN HANACARAKA PHILOSOPHY Fitriana Kartika Sari STKIP PGRI Ponorogo email: [email protected] Abstract (Title: The Local Wisdom In Javanese Thinking Culture Within Hanacaraka Philosophy). Hanacaraka refers to the written language of Javanese, Javanese script. The name is based on the order of the twenty-Javanese-script, which is started by the series of hanacaraka script. This study aims to describe the local wisdom content of Javanese Thinking culture within the philosophical meaning of hanacaraka. This study used a semiotic approach applied to the main data source, namely Sêrat Kérata Basa. The results showed that (1) the philosophical meaning of the hanacaraka script was fully equipped with the wisdom of Javanese thinking culture in the form of symbolism and othak-athik mathuk which is supported by deep contemplation which involves all the common senses, including the inner sensitivity; (2) hanacaraka philosophy depicts God creature’s (human) circumstances, which is equipped with creation, feeling, and effort; human cannot avoid all God’s fate upon them until the end of their life; human conditions that achieve life harmony due to the ability to unify the manifestation of God and human characteristics, which heats up within themselves; human condition which put God’s order highly by doing all the orders and avoiding all of His warnings. Keywords: local wisdom, Javanese thinking, Hanacaraka INTRODUCTION because human is always eager to know and Javanese local wisdom is the principal find the authentic truth for everything. Human factor of thoughtful thinking which covers tries to seek for the revelating indicator of all then aspects of knowledge, faith, mysteries deeply through the use of all the comprehension or understanding, customs, common senses to gain satisfying conclusive and ethics. -

2016 Semi Finalists Medals

2016 US Physics Olympiad Semi Finalists Medal Rankings StudentMedal School City State Abbott, Ryan WHopkinsBronze Medal SchoolNew Haven CT Alton, James SLakesideHonorable Mention High SchoolEvans GA ALUMOOTIL, VARKEY TCanyonHonorable Mention Crest AcademySan Diego CA An, Seung HwanGold Medal Taft SchoolWatertown CT Ashary, Rafay AWilliamHonorable Mention P Clements High SchoolSugar Land TX Balaji, ShreyasSilver Medal John Foster Dulles High SchoolSugar Land TX Bao, MikeGold Medal Cambridge Educational InstituteChino Hills CA Beasley, NicholasGold Medal Stuyvesant High SchoolNew York NY BENABOU, JOSHUA N Gold Medal Plandome NY Bhattacharyya, MoinakSilver Medal Lynbrook High SchoolSan Jose CA Bhattaram, Krishnakumar SLynbrookBronze Medal High SchoolSan Jose CA Bhimnathwala, Tarung SBronze Medal Manalapan High SchoolManalapan NJ Boopathy, AkhilanGold Medal Lakeside Upper SchoolSeattle WA Cao, AntonSilver Medal Evergreen Valley High SchoolSan Jose CA Cen, Edward DBellaireHonorable Mention High SchoolBellaire TX Chadraa, Dalai BRedmondHonorable Mention High SchoolRedmond WA Chakrabarti, DarshanBronze Medal Northside College Preparatory HSChicago IL Chan, Clive ALexingtonSilver Medal High SchoolLexington MA Chang, Kevin YBellarmineSilver Medal Coll PrepSan Jose CA Cheerla, NikhilBronze Medal Monta Vista High SchoolSan Jose CA Chen, AlexanderSilver Medal Princeton High SchoolPrinceton NJ Chen, Andrew LMissionSilver Medal San Jose High SchoolFremont CA Chen, Benjamin YArdentSilver Medal Academy for Gifted YouthIrvine CA Chen, Bryan XMontaHonorable -

An Introduction to Indic Scripts

An Introduction to Indic Scripts Richard Ishida W3C [email protected] HTML version: http://www.w3.org/2002/Talks/09-ri-indic/indic-paper.html PDF version: http://www.w3.org/2002/Talks/09-ri-indic/indic-paper.pdf Introduction This paper provides an introduction to the major Indic scripts used on the Indian mainland. Those addressed in this paper include specifically Bengali, Devanagari, Gujarati, Gurmukhi, Kannada, Malayalam, Oriya, Tamil, and Telugu. I have used XHTML encoded in UTF-8 for the base version of this paper. Most of the XHTML file can be viewed if you are running Windows XP with all associated Indic font and rendering support, and the Arial Unicode MS font. For examples that require complex rendering in scripts not yet supported by this configuration, such as Bengali, Oriya, and Malayalam, I have used non- Unicode fonts supplied with Gamma's Unitype. To view all fonts as intended without the above you can view the PDF file whose URL is given above. Although the Indic scripts are often described as similar, there is a large amount of variation at the detailed implementation level. To provide a detailed account of how each Indic script implements particular features on a letter by letter basis would require too much time and space for the task at hand. Nevertheless, despite the detail variations, the basic mechanisms are to a large extent the same, and at the general level there is a great deal of similarity between these scripts. It is certainly possible to structure a discussion of the relevant features along the same lines for each of the scripts in the set. -

UTC L2/20-061 2020-01-28 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale De Normalisation

UTC L2/20-061 2020-01-28 Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set International Organization for Standardization Organisation Internationale de Normalisation Doc Type: Working Group Document Title: Final Proposal to encode Western Cham in the UCS Source: Martin Hosken Status: Individual contribution Action: For consideration by UTC and ISO Date: 2020-01-28 Executive Summary. This proposal is to add 97 characters to a block: 1E200-1E26F in the supplementary plane, named Western Cham. In addition, 1 character is proposed for inclusion in the Arabic Extended A block: 08A0-08FF. The proposal is a revision of L2/19-217r3. A revision history is given at the end of the main text of this document. Introduction. Eastern Cham is already encoded in the range AA00-AA5F. As stated in N4734, Western Cham while closely related to Eastern Cham, is sufficiently different in style for Eastern Cham characters in plain text to be unintelligible to Western Cham readers and therefore a separate block is required. As such, the proposal to encode Western Cham in a separate block from (Eastern) Cham can be considered a disunification. But since Western Cham was never supported in the (Eastern) Cham block, it can be argued that this is a proposal for a new script. This is further discussed in the section on disunification. The Western Cham encoding follows the same encoding model as for (Eastern) Cham. There is no halant or virama that calls for a Brahmic model. The basic structure is a base character followed by a sequence of marks as described in the section on combining orders. -

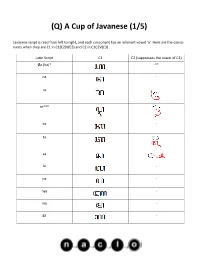

Q) a Cup of Javanese (1/5

(Q) A Cup of Javanese (1/5) Javanese script is read from left to right, and each consonant has an inherent vowel ‘a’. Here are the conso- nants when they are C1 in C1(C2)V(C3) and C2 in C1C2V(C3). Latin Script C1 C2 (suppresses the vowel of C1) Øa (ha)* -** na - ra re*** ka - ta sa la - pa - nya - ma - ga - (Q) A Cup of Javanese (2/5) Javanese script is read from left to right, and each consonant has an inherent vowel ‘a’. Here are the conso- nants when they are C1 in C1(C2)V(C3) and C2 in C1C2V(C3). Latin Script C1 C2 (suppresses the vowel of C1) ba nga - *The consonant is either ‘Ø’ (no consonant) or ‘h,’ but the problem contains only the former. **The ‘-’ means that the form exists, but not in this problem. ***The CV combination ‘re’ (historical remnant of /ɽ/) has its own special letters. ‘ng,’ ‘h,’ and ‘r’ must be C3 in (C1)(C2)VC3 before another C or at the end of a word. All other consonants after V must be C1 of the next syllable. If these consonants end a word, a ‘vowel suppressor’ must be added to suppress the inherent ‘a.’ Latin Script C3 -ng -h -r -C (vowel suppressor) Consonants can be modified to change the inherent vowel ‘a’ in C1(C2)V(C3). Latin Script V* e** (Q) A Cup of Javanese (3/5) Latin Script V* i é u o * If C2 is on the right side of C1, then ‘e,’ ‘i,’ and ‘u’ modify C2. -

The Particle Ma in Old Sundanese Aditia Gunawan, Evi Fuji Fauziyah

The particle ma in Old Sundanese Aditia Gunawan, Evi Fuji Fauziyah To cite this version: Aditia Gunawan, Evi Fuji Fauziyah. The particle ma in Old Sundanese. Wacana, Journal of the Humanities of Indonesia, Faculty of Humanities,University of Indonesia, 2021, Languages of Nusantara I, 22 (1), pp.207-223. 10.17510/wacana.v22i1.1040. hal-03193257 HAL Id: hal-03193257 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03193257 Submitted on 11 May 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. PB Wacana Vol. 22 No. 1 (2021) Aditia Gunawan andWacana Evi Fuji Vol. Fauziyah 22 No. 1 ,(2021): The particle 207-223 ma in Old Sundanese 207 The particle ma in Old Sundanese Aditia Gunawan and Evi Fuji Fauziyah ABSTRACT This article will analyse the distribution of the particle ma in Old Sundanese texts. Based on an examination of fifteen Old Sundanese texts (two inscriptions, eight prose texts, and five poems), we have identified 730 occurrences ofma . We have selected several examples which represent the range of its grammatical functions in sentences. Our observations -

Iso/Iec Jtc1/Sc2/Wg2 L2/12-322

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N4330 L2/12-322 2012-09-27 Title: Proposal to Encode the SANDHI MARK for Sharada Source: Script Encoding Initiative (SEI) Author: Anshuman Pandey ([email protected]) Status: Liaison Contribution Action: For consideration by UTC and WG2 Date: 2012-09-27 1 Introduction This is a preliminary proposal to encode a new character in the Sharada block of the Universal Character Set (ISO/IEC 10646). Properties of the proposed character are: 111C9 Po 0 L N AL 2 Description The is used in some Sharada manuscripts for indicating external sandhi in Sanskrit documents. It is a below-base mark that is written after the syllable where sandhi occurs. The excerpt below, from Bhagavad Gītā 1.1, illustrates usage of the mark (adapted from Lokesh Chandra 1982): Here the occurs in the phrases pāṇḍavāścaiva and kimakurvata . In the first phrase, it indicates ⃓ + + ⃓ vowel sandhi between ca and eva (°a e° → °ai°); in the second it indicates fusion of a bare consonant and a vowel between kim and akurvata (°m a° → °ma°). In this manuscript of the BG, the is written twice in order to indicate sandhi between two long vowels, as in the following excerpt from BG 2.1: 1 Proposal to Encode the SANDHI MARK for Sharada Anshuman Pandey Here the doubled mark occurs in the phrase kr̥ payāvisṭ aṃ , where it indicates sandhi of identical long vowels ++ between kr̥ payā and āvisṭ aṃ (°ā ā° → °ā°). However, the double is not consistently through- out the manuscript for marking long-vowel sandhi. 3 Relationship to Avagraha The graphical shape of is similar to that of ᇁ +111C1 . -

The Unicode Standard, Version 3.0, Issued by the Unicode Consor- Tium and Published by Addison-Wesley

The Unicode Standard Version 3.0 The Unicode Consortium ADDISON–WESLEY An Imprint of Addison Wesley Longman, Inc. Reading, Massachusetts · Harlow, England · Menlo Park, California Berkeley, California · Don Mills, Ontario · Sydney Bonn · Amsterdam · Tokyo · Mexico City Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book, and Addison-Wesley was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial capital letters. However, not all words in initial capital letters are trademark designations. The authors and publisher have taken care in preparation of this book, but make no expressed or implied warranty of any kind and assume no responsibility for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental or consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained herein. The Unicode Character Database and other files are provided as-is by Unicode®, Inc. No claims are made as to fitness for any particular purpose. No warranties of any kind are expressed or implied. The recipient agrees to determine applicability of information provided. If these files have been purchased on computer-readable media, the sole remedy for any claim will be exchange of defective media within ninety days of receipt. Dai Kan-Wa Jiten used as the source of reference Kanji codes was written by Tetsuji Morohashi and published by Taishukan Shoten. ISBN 0-201-61633-5 Copyright © 1991-2000 by Unicode, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or other- wise, without the prior written permission of the publisher or Unicode, Inc. -

Downloaded From

H. Creese Old Javanese studies; A review of the field In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, Old Javanese texts and culture 157 (2001), no: 1, Leiden, 3-33 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com09/27/2021 04:40:52AM via free access HELEN CREESE Old Javanese Studies A Review of the Field For nearly two hundred years the academic study of the languages and liter- atures of ancient Java has attracted the attention of scholars. Interest in Old Javanese had its genesis in the Orientalist traditions of early nineteenth-cen- tury European scholarship. Until the end of the colonial period, the study of Old Javanese was dominated by Dutch scholars whose main interest was philology. Not surprisingly, the number of researchers working in this field has never been large, but as the field has expanded from its original philo- logical focus to encompass research in a variety of disciplines, it has remain1 ed a small but viable research area in the wider field of Indonesian studies. As a number of recent review articles have shown (Andaya and Andaya 1995; Aung-Thwin 1995; McVey 1995; Reynolds 1995), in the field of South- east Asian studies as a whole, issues of modern state formation and devel- opment have dominated the interest of scholars and commentators. Within this academic framework, interest in the Indonesian archipelago in the period since independence has also focused largely on issues relating to the modern Indonesian state; This focus on national concerns has not lent itself well to a .rich ongoing scholarship on regional cultures, whether ancient or modern. -

Docket No. 2011-0206 Reliability Standards Working Group Monthly

Hawaiian Electric Company, Inc. • PO Box 2750 • Honolulu, HI 96840-0001 FILED 2fl[ii APR 25' P 3=52 PUBLIC UTILITIES COMMISSION April 25, 2014 The Honorable Chair and Members of the Hawai'i Public Utilities Commission Kekuanaoa Building, 1st Floor 465 South King Street Honolulu, HawaiM 96813 Dear Commissioners: Subject: Docket No. 20! 1-0206 Reliability Standards Working Group Monthly Report Pursuant to Ordering Paragraph 3 of the Commission's Order No. 30371, filed on May 4, 2012, in the above subject proceeding, enclosed as Exhibit A is the Hawaiian Electric Companies'' monthly report for March 2014 on (1) system frequency control performance during month; (2) significant system events during month; and (3) curtailment of non- dispatchable renewable resources. In addition, an electronic copy of each report is also included with this filing. These files are voluminous, and therefore, the Company is providing a compact disc ("CD") containing the electronic files to both the Commission and the Consumer Advocate. Copies of the CD will be available to any Party to this proceeding. Interested Parties should email Marisa Chun at [email protected] to request a copy. If you have any questions on this matter, please contact Marisa Chun at (808) 543-4723. Sincerely, Daniel G. Brown Manager Regulatory Non-Rate Proceedings Enclosure cc: Service List Hawaiian Eleciric Company, Inc., Hawai'i Electric Light Company, Inc., and Maui Electric Company, Limited are collectively referred to as the "Hawaiian Electric Companies" or "Companies". SERVICE LIST (Docket No. 2011-0206) JEFFREY T. ONO 2 Copies EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Via Hand Delivery DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE AND CONSUMER AFFAIRS DIVISION OF CONSUMER ADVOCACY P.O.