JOURNALISTS CAUGHT BETWEEN TWO FIRES Hong Kong Media Faces Serious Harassment and Self-Censorship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Realities of State-By-State Suitability Determinations and the Need for Federal Regulation

CLAY ARTICLE (DO NOT DELETE) 4/2/2018 1:07 PM PLAYING THE ODDS: THE REALITIES OF STATE-BY-STATE SUITABILITY DETERMINATIONS AND THE NEED FOR FEDERAL REGULATION Daniel N. Clay INTRODUCTION With some exceptions, gaming in the United States is a growing industry.1 While commercial casino revenue peaked in 2007, which was followed by a sharp decline at the height of the Great Recession, in 2012 national gaming revenues reached the second highest level in history.2 Not only has the rebound translated into increased revenues, employment rates, and economic development — it has also led to sharp increases in gaming tax revenue for the vast majority of states that permit commercial casinos — Kansas,3 Maryland,4 Maine,5 and New York6 are most notable.7 As discussed below, while gaming heavily impacts interstate commerce, the industry is still governed by a patchwork of differing state laws.8 This article seeks to show that these inconsistencies in state law are especially prevalent in state-by-state suitability determinations, in which states may disagree about the suitability for licensure of a single casino applicant or otherwise make conflicting determinations of similarly situated applicants.9 Moreover, this article argues that such inconsistencies, coupled with the lack of meaningful judicial review, have caused uncertainty for would-be applicants, and in turn necessitates meaningful 1 See Am. Gaming Ass’n, State of the States: The AGA Survey of Casino Entertainment, at ii (2013), https://www.americangaming.org/sites/default/files/ research_files/aga_sos2013_rev042014.pdf. 2 See id. 3 Id. at 6 (reporting a 604.7% increase in gaming tax revenue during FY 2012). -

Market Research 2020

THE ITALIAN TRADE COMMISSION HONG KONG MARKET RESEARCH FILM 2020 SEPTEMBER F O S B A C K G R O U N D E Hong Kong Current Market Overview L 2 T S T A T I S T I C B A Hong Kong Box Office & Market Trend T 4 N S T A T I S T I C 5 Audio & Visual Equipment Industry E L O C A L F I L M I N D U S T R Y T 7 Loca Industry and Distribution G L O B A L D I S T R I B U T I O N N 8 International Investment and Recognition T E L E V I S I O N I N D U S T R Y O 10 Local TV Industry T R A D E S H O W C 1 1 Hong Kong FILMART A S S O C I A T I O N S 12 Hong Kong Trade Associations (Film Sector) R E F E R E N C E 13 Source and Reference BACKGROUND: V O L U M E 3 , I S S U E 3 HONG KONG CURRENT MARKET OVERVIEW Business Shock Under COVID-19 CINEMA CLOSED DUE TO CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC Under the tightened social distancing policies announced by the HKSAR government to fight against the coronavirus, cinemas were previously closed twice from March 27 to May 5 and July 15 to August 27 Hong Kong box office receipts plunged by more than 70% in the first six months of 2020 as audiences stayed away and cinemas shut down amid the coronavirus pandemic. -

Broadcasting Ordinance (Chapter 562) Notice Is Hereby Given That The

Broadcasting Ordinance (Chapter 562) Notice is hereby given that the Broadcasting Authority has received an application from City Telecom (H.K.) Limited, a company duly incorporated in Hong Kong whose registered office is situated at Level 39, Tower 1, Metroplaza, No. 223 Hing Fong Road, Kwai Chung, N.T., for a domestic free television programme service licence. The particulars of the application in this Notice, as set out below, are provided by City Telecom (H.K.) Limited. Nothing in this notice shall affect or prejudice any powers, discretion and rights of the Broadcasting Authority or the Government. 1. COMPANY INFORMATION Principal shareholders City Telecom (H.K.) Limited (“CTI”) is a publicly listed company in Hong Kong under HKEx (Stock Code: 1137) and the U.S. under NASDAQ (Ticker Symbol: CTEL). As at 6 July 2010, the company’s shares are held by Top Group International Limited (44.42%) and other shareholders including Mr Ricky Wong Wai Kay (0.93%), Mr Lai Ni Quiaque and Mrs Lai Michelle Pek Lian (1.36%), Mr Paul Cheung Chi Kin (2.27%), Worship Limited (3.26%) and general public (47.46%). Compliance with statutory requirements (a) CTI submits that it is a company registered and incorporated in Hong Kong under the Companies Ordinance (Cap. 32) in 1992. (b) CTI submits that it is not a subsidiary of a corporation1. (c) CTI submits that the company and all persons exercising control of the company will be and remain fit and proper persons2. 1 Section 8(3) of the Broadcasting Ordinance and section 2 of Schedule 4 to the Ordinance prohibit a domestic free television programme service licence to be granted to or held by a company which is the subsidiary of a corporation. -

Web Proof Information Pack of MGM

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited, The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited and the Securities and Futures Commission take no responsibility for the contents of this Web Proof Information Pack, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this Web Proof Information Pack. Web Proof Information Pack of MGM CHINA HOLDINGS LIMITED (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) WARNING The Web Proof Information Pack is being published as required by The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited and the Securities and Futures Commission solely for the purpose of providing information to the public in Hong Kong. This Web Proof Information Pack is in draft form. The information contained in it is incomplete and is subject to change which can be material. By viewing this Web Proof Information Pack, you acknowledge, accept and agree with MGM China Holdings Limited (the “Company”), any of its affiliates, sponsors and advisers and members of the underwriting syndicate that: (a) this Web Proof Information Pack is only for the purpose of providing information and facilitating equal dissemination of information to investors in Hong Kong and not for any other purposes. No investment decision should be based on the information contained in this Web Proof Information Pack; (b) the posting of this Web Proof Information Pack or any supplemental, revised or replacement pages on the website of Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited does not give rise to any obligation of the Company, its affiliates, sponsors and advisers or members of the underwriting syndicate to proceed with any offering in Hong Kong or any other jurisdiction. -

CTB(CR)9/3/10 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL BRIEF Broadcasting

File Ref : CTB(CR)9/3/10 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL BRIEF Broadcasting Ordinance (Chapter 562) Applications for Domestic Free Television Programme Service Licences INTRODUCTION At the meeting of the Executive Council on 15 October 2013, in connection with the three applications for domestic free television programme service (“free TV”) licences from Hong Kong Television Network Limited (“HKTVN”), Fantastic Television Limited (“Fantastic TV”) and HK Television Entertainment Company Limited (“HKTVE”) (collectively as the “Applicants”) submitted under the Broadcasting Ordinance (Cap. 562) (“BO”) (individually as a “free TV licence application” and collectively as the “free TV licence applications”), having considered all relevant factors set out at Annex A, the Council ADVISED and the Chief Executive (“CE”) ORDERED that – (a) the “Gradual and Orderly Approach” referred to in paragraph 13 below be adopted in considering the free TV licence applications; (b) Fantastic TV’s and HKTVE’s free TV licence applications be granted approval-in-principle (“AIP”), subject to CE in Council’s further review and final determination at the Second Stage1, whilst HKTVN’s free TV licence application be rejected; (c) the free TV licences that may be granted to Fantastic TV and HKTVE be prepared and submitted to the CE in Council for consideration and, if appropriate, approval at the Second Stage, with licensing conditions which should broadly be along the lines set out in Annex B; and 1 This means the later stage when the CE in Council is invited to consider whether or not to formally grant a free TV licence under sections 8(1) and 10(1) of the BO to the Applicant(s) to which AIP is granted. -

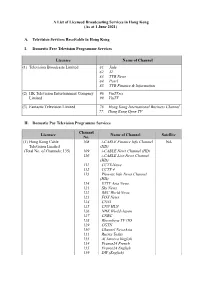

A List of Licensed Broadcasting Services in Hong Kong (As at 1 June 2021)

A List of Licensed Broadcasting Services in Hong Kong (As at 1 June 2021) A. Television Services Receivable in Hong Kong I. Domestic Free Television Programme Services Licensee Name of Channel (1) Television Broadcasts Limited 81. Jade 82. J2 83. TVB News 84. Pearl 85. TVB Finance & Information (2) HK Television Entertainment Company 96. ViuTVsix Limited 99. ViuTV (3) Fantastic Television Limited 76. Hong Kong International Business Channel 77. Hong Kong Open TV II. Domestic Pay Television Programme Services Channel Licensee Name of Channel Satellite No. (1) Hong Kong Cable 108 i-CABLE Finance Info Channel NA Television Limited (HD) (Total No. of Channels: 135) 109 i-CABLE News Channel (HD) 110 i-CABLE Live News Channel (HD) 111 CCTV-News 112 CCTV 4 113 Phoenix Info News Channel (HD) 114 ETTV Asia News 121 Sky News 122 BBC World News 123 FOX News 124 CNNI 125 CNN HLN 126 NHK World-Japan 127 CNBC 128 Bloomberg TV HD 129 CGTN 130 Channel NewsAsia 131 Russia Today 133 Al Jazeera English 134 France24 French 135 France24 English 139 DW (English) - 2 - Channel Licensee Name of Channel Satellite No. 140 DW (Deutsch) 151 i-CABLE Finance Info Channel 152 i-CABLE News Channel 153 i-CABLE Live News Channel 154 Phoenix Info News 155 Bloomberg 201 HD CABLE Movies 202 My Cinema Europe HD 204 Star Chinese Movies 205 SCM Legend 214 FOX Movies 215 FOX Family Movies 216 FOX Action Movies 218 HD Cine p. 219 Thrill 251 CABLE Movies 252 My Cinema Europe 253 Cine p. 301 HD Family Entertainment Channel 304 Phoenix Hong Kong 305 Pearl River Channel 311 FOX 312 FOXlife 313 FX 317 Blue Ant Entertainment HD 318 Blue Ant Extreme HD 319 Fashion TV HD 320 tvN HD 322 NHK World Premium 325 Arirang TV 326 ABC Australia 331 ETTV Asia 332 STAR Chinese Channel 333 MTV Asia 334 Dragon TV 335 SZTV 336 Hunan TV International 337 Hubei TV 340 CCTV-11-Opera 341 CCTV-1 371 Family Entertainment Channel 375 Fashion TV 376 Phoenix Chinese Channel 377 tvN 378 Blue Ant Entertainment 502 Asia YOYO TV 510 Dreamworks 511 Cartoon Network - 3 - Channel Licensee Name of Channel Satellite No. -

LC Paper No. CB(4)330/17-18(05)

立法會 Legislative Council LC Paper No. CB(4)330/17-18(05) Ref. : CB4/PL/ITB Panel on Information Technology and Broadcasting Meeting on 11 December 2017 Updated background brief on the progress of the implementation of digital terrestrial television broadcasting in Hong Kong Purpose This paper sets out the background of the implementation of digital terrestrial television ("DTT") broadcasting in Hong Kong, and summarizes the views and concerns previously expressed by Members. Background Implementation framework for DTT broadcasting 2. The Administration announced the implementation framework of DTT broadcasting in 2004. The implementation of DTT helps fulfil the policy to enhance and promote Hong Kong's information infrastructure and services to build Hong Kong into a leading digital city in the globally connected world of the 21st century. The Administration's priority is to ensure a smooth analogue- to-digital migration of existing terrestrial television ("TV") services by broadcasters building and testing the digital broadcasting network and launching new TV or multimedia services to drive consumer take-up of DTT. Digital terrestrial television services by free TV licensees 3. On 22 February 2016, the Television Broadcasts Limited ("TVB") ceased the simulcast arrangement on its Jade and HD Jade channels, where the same TV programme content was simultaneously broadcast on the two TVB channels. The HK Television Entertainment Company Limited ("HKTVE") launched its new integrated Chinese channel, ViuTV, via fixed network since - 2 - 31 March 2016 and has started to transmit its DTT service from 2 April 2016; the integrated English channel was launched on 31 March 2017. 4. The transmission network of HKTVE and TVB cover at least 99% of the Hong Kong population 1 . -

S Ho Partnership

Regulators set to discuss MGM’s Ho partnership The common perception about Benjamin „Bugsy“ Siegel is that he had numerous associations with gangsters and organized crime in the early days of Las Vegas‘ gambling industry. Eventually, his Flamingo Hotel became a successful property in the center of the Las Vegas Strip and it’s now owned by Harrah’s Entertainment, one of the most respected brands in the industry. In a parallel universe half a world away, octogenarian Stanley Ho has built a casino empire that critics say has had ties to the Triad, a shady gang of Asian gangsters. Ho denies that he’s ever had any associations with loan sharks, prostitution or illegal gambling. But Ho’s estranged sister says he has. The burning question that representatives of the state Gaming Control Board will be asking in a hearing to be conducted soon in Las Vegas is: Does Stanley Ho exercise control over or influence on daughter Pansy Ho’s casino partnership? The question has incredible implications for MGM Mirage, which is partnering with Pansy Ho on two projects in Macau. MGM Mirage Chairman Terry Lanni and Pansy Ho are the key members of MGM Grand Paradise, the company that is building the MGM Grand Macau next door to Steve Wynn’s Wynn Macau property that opened in September. Right across the street from Wynn is Stanley Ho’s Lisboa casino, the Macanese version of Las Vegas‘ Flamingo – it’s got a notorious history to it, but face-lifts, including an expansion that opened last week, have made it a favorite hangout for locals even as the new American companies moved in. -

BUSINESS OVERVIEW Our Subsidiary, MGM Grand Paradise, Is

BUSINESS OVERVIEW Our subsidiary, MGM Grand Paradise, is one of the leading casino gaming resort developers, owners and operators in the greater China region and holds one of the six gaming concessions/ subconcessions in Macau. According to the DICJ, for the month of December 2010, in terms of revenue, we held an approximate 11.4% market share out of the 33 casinos in Macau. We currently own and operate MGM Macau, a premium integrated casino resort on the Macau Peninsula. In addition, we are also exploring growth opportunities in Cotai, the other key area of casino gaming development in Macau. We have identified a site of approximately 17.8 acres in Cotai and have submitted an application to the Macau Government to obtain the right to lease this parcel of land. We are awaiting approval of this application. We benefit from the complementary expertise of MGM Resorts International and Pansy Ho. Immediately following the completion of the Global Offering, our controlling shareholder will be MGM Resorts International (with an interest in 51% of our issued share capital) and Pansy Ho and her controlled companies will be our substantial shareholder (with an interest in 29% of our issued share capital, assuming the Over-allotment Option is not exercised). As a result of the relationship between MGM Resorts International and Pansy Ho in respect of our Company following the completion of the Global Offering and the arrangements in place under the Voting Agreement, MGM Resorts International and Pansy Ho will be considered to be parties acting in concert (as that term is defined in the Takeovers Code) in relation to our Company. -

Mr. Ronnie C CHAN Dr. Roy CHUNG Mr. Franklin

The Better Hong Kong Foundation Delegation to the United States Mr. Ronnie C CHAN Co-Leader of the Delegation Executive Committee Chairman, The Better Hong Kong Foundation Chairman, Hang Lung Properties Ltd Mr. Ronnie C. Chan is the Chairman of Hang Lung Group Ltd and its subsidiary Hang Lung Properties Ltd. Both are publicly listed companies in Hong Kong. Hang Lung has been a leader in Hong Kong’s property market for over 50 years, and has been expanding into mainland China since 1992. Following successes in Shanghai, Hang Lung has been investing US$11 billion and building a number of world-class commercial complexes in Tianjin, Shenyang, Jinan, Wuxi, Dalian, Kunming and Wuhan. Mr. Chan co-founded the privately held Morningside group. In addition, he is Chairman of the Executive Committees of the One Country Two Systems Research Institute and of the Better Hong Kong Foundation. He founded and chairs the China Heritage Fund, is a co-founding director of The Forbidden City Cultural Heritage Conservation Foundation, Beijing, and is an Advisor and former Vice President of the China Development Research Foundation in Beijing. Internationally, Mr. Chan is a Co-Chair of the Board of the Asia Society and Chairman of its Hong Kong Center, a Director of the Board of the Peter G. Peterson Institute for International Economics and a member of the Council on Foreign Relations, the National Committee on United States-China Relations, and the Committee of 100. He is the founding Chairman Emeritus of the Asia Business Council, a former Chairman of the Hong Kong-United States Business Council, and a former member of the governing board of the World Economic Forum. -

RTHK Annual Plan for 2019/20

RTHK Annual Plan for 2019/20 Purpose The purpose of this annual plan is to inform the public of Radio Television Hong Kong’s (RTHK) programming outline for the year 2019/20 and to provide a basis for public scrutiny of the extent to which RTHK fulfills the public purposes and mission as set out in the RTHK Charter. The public purposes and mission of RTHK are - (a) to sustain citizenship and civil society; (b) to provide an open platform for the free exchange of views without fear or favour; (c) to encourage social inclusion and pluralism; (d) to promote education and learning; and (e) to stimulate creativity and excellence to enrich the multi-cultural life of Hong Kong people. For details of RTHK’s public purposes and mission, please refer to the RTHK Charter at: http://rthk9.rthk.hk/about/pdf/charter_eng.pdf . Overview 2. For 2019/20, RTHK will pursue objectives in the following four areas - (a) Programme Direction In accordance with the RTHK Charter, RTHK produces quality programmes that inform, educate and entertain the public in wide-ranging topics, underlined with creativity and responsibility in Page 1 RTHK Annual Plan for 2019/20 content development. RTHK will partner with government bureaux / departments and non-governmental organizations for quality programme production. Key programming directions for 2019/20 of RTHK are: (i) Healthy Hong Kong (健康香港) will be the main theme for RTHK programming this year; (ii) Produce programmes to promote sports as an instrument to enhance physical and mental health, provide sports news and live -

Download Firmware Remotely to the Relationships and Superior Service in Our Regions

August 2009 • MOP 30 • ISSN 2070-7681 Steady As She Goes? Under Macau’s new Chief Executive Atronic: Big DEAL Singapore: Bay Watch Transact: Fit to Print The ‘G6’ Noteworthy Promotions In Focus: Integrated Resort 2.0 INSIDE ASIAN GAMING | August 2009 CONTENTS August 2009 Handle With Care 7 7 Cover Story 12 Bay Watch 18 Dynasty 20 Fit to Print 23 The “G6” 26 Integrated Resort 2.07 28 Table to Cage 30 Losing Some Steam 33 33 Big DEAL 36 Cadillac Jack 39 Noteworthy Promotions 44 Regional Briefs 46 International Briefs 48 Events Calendar 39 August 2009 | INSIDE ASIAN GAMING 2 INSIDE ASIAN GAMING | August 2009 August 2009 | INSIDE ASIAN GAMING 3 Editorial Wind of Change The gaming industry, perhaps more than many other industries, relies on big personalities and a supportive political framework. Events of the last few weeks have shown how quickly things can change. First there was the signalling of a change of personnel at the top in Macau politics. Fernando Chui Sai On was confirmed as the Chief Executive-elect and will take over from the incumbent Edmund Ho in December—the tenth anniversary of Macau’s return to Chinese administration. Second there was the hospitalisation of 87-year old Dr Stanley Ho, the founder of the modern Macau gaming industry. He underwent surgery for a blood clot on his brain—an operation necessitated reportedly after a fall at home. As far as Mr Chui’s appointment is concerned, many commentators on Macau are predicting more of the same. That means a largely hands-off, arms-length approach to the industry—in terms of giving it as much freedom as possible to generate wealth for the local community, within the framework of international standard regulation.