Appendix II: Deaths at Penrhyn Quarry 1842

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preparing for the Global Citizenship Mini Challenge

KS4 NATIONAl/FOUNDATION WELSH BaccaLAUREATE Amgueddfa Cymru - National Museum Wales Preparing for the Global Citizenship Mini Challenge SOURCE PACK We can learn a lot about the issue of poverty and inequality today by studying Welsh history as well as examples from the world today. Study these sources about poverty and inequality in the slate industry in north Wales in the 19th century and the textile or clothing industry in modern Cambodia. The sources will help you to understand why workers are paid low wages, how they have protested and fought through trade unions to improve their lives and how their efforts have been opposed by those who stand to profit from the industry. If you would like to know more why not visit the National Slate Museum in Llanberis, north Wales. You can also research websites such as the Gwynedd Archives Slatesite. More can be found on the National Archives website and on the Welsh Government learning resources hwb. ISSUE: POVERTY FOCUS: INEQUALITY (cover image: Jezper/shuttersTOCK.com) (cover image: SOURCE 1: The National Wool Museum at Dre-fach Felindre, West Wales SOURCE 1: Adapted from a report in the north Wales newspaper the Daily Post, 22 June, 2013 The Great Strike at Penrhyn Slate Quarry, near Bethesda, out in protest, marking the beginning of the Great Strike, which north Wales, lasting from 1900 to 1903, was one of the largest lasted for three years. ever seen in Britain. The strikers received generous support, including a huge By 1900 Penrhyn was the world’s largest slate quarry, Christmas pudding, weighing two and a half tonnes from a worked by nearly 3,000 quarrymen. -

Penrhyn Quarry and Changes to the Form of Two Tips (As Described in Chapter 3 Above)

CULTURAL HERITAGE 8 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 8-1 Scope of this Report ............................................................................................................................... 8-1 METHODOLOGY .......................................................................................................................... 8-2 Desk Based Research .............................................................................................................................. 8-2 Field-based research ............................................................................................................................... 8-3 Scoping and Consultations ...................................................................................................................... 8-3 Assessment Methodology and Significance Criteria ............................................................................... 8-3 Relevant Legislation, Policy and Guidance .............................................................................................. 8-5 BASELINE CONDITIONS .............................................................................................................. 8-13 Designated Heritage Assets .................................................................................................................. 8-13 Archaeological Background ................................................................................................................. -

Zones of Influence

Eryri Local Development Plan Background Paper 21 Zones of Influence May 2017 Background Paper 21: Zones of Influence – May 2017 Introduction The Authority has identified eight ‘Zones of influence’ which are within and straddle the National Park. These areas have similar characteristics and have strong community links. The work on the Zones of Influence draws on a wide range of surveys and related national, regional and local plans and strategies discussed in the Spatial Development Strategy Background Paper. The paper identifies key centres within each zone of influence and recognises the influences of key centres outside the Park to inform the Spatial Development Strategy. The paper identifies key transport routes, key employment areas, and further education and key services for each zone. The paper discusses the main issues for each zone individually, the implications for the Local Development Plan and how the issues are addressed in the Plan. 2 Background Paper 21: Zones of Influence – May 2017 1.1. BALA ZONE OF INFLUENCE 3 Background Paper 21: Zones of Influence – May 2017 What’s it like now? 1.2. This zone covers Penllyn rural hinterland covering the community councils of Llanuwchllyn, Llandderfel, Llangywer, Llanycil and Bala and has a population of 4,362 according to the 2011 Census. The landscape is rural in character with scattered farmsteads and small villages. The zone includes Llyn Tegid (the largest natural lake in Wales), Llyn Celyn, Arenig Fawr and parts of the Aran Fawddwy. The main service centre for the area is the market town of Bala. Penllyn has strong traditions based on the Welsh language and culture. -

Llandygai Date Amended 24/05/2000 Locality Llandygai Date Delisted Grid Ref 260076 370987 Grade II*

Detail Report Authority Gwynedd Record No 3657 Date Listed 03/03/1966 Community Llandygai Date Amended 24/05/2000 Locality Llandygai Date Delisted Grid Ref 260076 370987 Grade II* Name Church of St Tegai Location Located at north-eastern end of village. History Nave retains small elements of C14 fabric at east end; chancel and transepts built in C16, the whole much restored by Henry Kennedy at the expense of Edward Douglas-Pennant, first Baron Penrhyn, in 1853 when the nave was lengthened, its windows replaced and the parapets above original string course rebuilt; the present central tower (replacing C16 one demolished in that year), west porch and north vestry were also added at this time. An earlier church, claimed to be of C6 origin, is said to have stood nearby. Exterior Cruciform parish church consisting of nave, chancel, central tower, transepts, north vestry and west porch. Roughly coursed rubblestone to nave, chancel and transepts with ashlar to parapets concealing shallow-pitched lead roofs; rock-faced ashlar to tower. Nave buttressed in 2 bays has mid-C19 3-light windows with panel tracery on both north and south, those to west with hoodmoulds; north side also has small rectangular window lighting gallery at west end; embattled parapets, including to west porch which has pointed and nook-shafted outer doorway with quatrefoils and trefoils to spandrels of square label; single-light trefoil-headed windows to sides and pointed inner doorway with Decorated-style tracery to door. Chancel has 5-light east window with hollow spandrels in 4-centred arch with hoodmould; similar windows in 3 lights to north and south but without hoodmoulds, north blocked; below and to right of east window is narrow infilled doorway with slate voussoirs (entrance to C19 burial vault). -

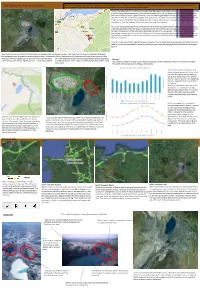

Site Analysis: Penryhn Quarry

Site Analysis: Penryhn Quarry Aim: To research my chosen location of Penryhn quarry and consider all of the factors that I think will influence the function, aesthetics and manufacture of my building with special interest into weather conditions that could be incorporated into a more environmentally friendly design. The Penrhyn Slate Quarry is a slate quarry located near Bethesda in north Wales. At the end of the nineteenth century it was the world's largest slate quarry; the main pit is nearly 1 mile (1.6 km) long and 1,200 feet (370 metres) deep, and it was worked by nearly 3,000 quarrymen. It has since been superseded in size by slate quarries in China, Spain and the USA. Penrhyn is still Britain's largest slate quarry but its workforce is now nearer 200. It was owned from the 1780's by the Pennant family and rapidly developed as a major industrial unit. The majority of quarrying was still small scale at that time and was being carried on as an aside from farming. The quarry was first developed in the 1770s by Richard Pennant, later Baron Penrhyn although it is likely that small- scale slate extraction on the site began considerably earlier. Much of this early working was for domestic use only as no large scale transport infrastructure was developed until Pennant's involvement. From then on, slates from the quarry were transported to the sea at Port Penrhyn on the narrow gauge Penrhyn Quarry Railway built in 1798, one of the earliest railway lines. In the 19th century the Penrhyn Quarry, along with the Dinorwic Quarry, dominated the Welsh slate industry. -

Der North Wales Way

Der North Wales Way Ein Kurztrip durch die Jahrhunderte thewalesway.com northeastwales.wales visitconwy.org.uk visitsnowdonia.info visitanglesey.co.uk Wo ist Wales? So kommen Sie nach Wales. Wales ist gut angebunden an alle größere britische Städte, wie z.B. London, Birmingham, Manchester und Liverpool. Wales hat seinen eigenen Flughafen, Cardiff International Airport (CWL), mit mehr als 50 Direktflüge zu europäischen Großstädten und zu über 1.000 Zielen weltweit. Wales ist ebenfalls gut angebunden an Bristol (BRS), Birmingham (BHX), Manchester (MAN) und Liverpool (LPL) Flughafen. 2 Stunden mit dem Zug von London 3 Stunden Autofahrt von Central London, 1 Std Autofahrt von Liverpool, Manchester, Bristol und Birmingham. Der Flughafen Cardiff bietet Direktflüge nach ganz Europa an, sowie weltweite Verbindungen über die Flughäfen Doha, Schipol und Dublin. cardiff-airport.com Direkte Fährverbindungen von irischen Häfen AONB Ein Gebiet gekennzeichnet durch „Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB)“ - ein Gebiet von aussergewöhnlicher natürlicher Schönheit - ist eine gekennzeichnete, aussergewöhnliche Landschaft dessen einzigartiger Charakter und natürliche Schönheit so wertvoll ist, daß es im nationalen Interesse geschützt wird. Wales hat 5 Gebiete von herausragender natürlicher Schönheit (AONB): • Anglesey • die Clwydianische Bergkette und das Dee Tal • die Gower-Halbinsel • die Llŷn-Halbinsel • das Wye Tal Obwohl alle Anstrengungen unternommen wurden, um die Richtigkeit dieser Veröffentlichung zu gewährleisten, können die Herausgeber keinerlei Haftung für Fehler, Ungenauigkeiten oder Auslassungen oder für irgendwelche mit der Veröffentlichung der Informationen verbundenen oder daraus entstehenden Probleme übernehmen. Bitte überprüfen Sie alle Preise und Einrichtungen, bevor Sie Ihre Buchung vornehmen. Wenn Sie mit der Anleitung fertig sind, wollen Sie diese nicht an einen Freund oder Freundin weiterleiten? Alternativ geben Sie diese bitte in einen geeigneten Recyclingbehälter. -

10) Port Penrhyn and the 1800 Horse Tramway Slates from What Became

10) Port Penrhyn and the 1800 horse tramway Slates from what became the workings of Penrhyn Quarries have been shipped from Abercegin near Bangor since about 1700. Originally boats were loaded on the beach at low tide, but the great increase in demand that marked the onset of the Industrial Revolution resulted in the development from 1780 of the present extensive facilities on the site that became known as Port Penrhyn. The Penrhyn Railway, running down to here from the Quarries near Bethesda, was first built as a horse tramway in 1800-1 then replaced by a 1 ft 10¾ in gauge locomotive-worked line on a different route circa 1878. The latter remained in use until June 1962, since when lorries have conveyed a very much-reduced traffic for shipment at the Port. The quays were also served by a standard gauge siding from the Chester & Holyhead line, opened in 1852 and removed in 1963, which allowed transhipment onto the main railway network. Our plan shows all these routes, also the L&NWR branch line from Bethesda Junction, Bangor to Bethesda…… Our composite plan of the quays was compiled in October 1966, at which time the standard-gauge tracks had been removed, but there course was still evident. The narrow-gauge lines were still intact, but were removed just a few weeks later. The functions of the various buildings were explained to us by Iorwerth Jones, a former locomotive driver on the Penrhyn Railway…… Although Port Penrhyn today is occasionally visited by a coasting vessel from mainland Europe (as seen in our picture right) to take on a cargo of slate brought down from the quarry by road, the quays are now the province of the local fishing fleet, the Straits' sand-dredger and civil engineering and building contractors. -

The Wales Way Is a New Family of Three National Touring Routes That Lead You Along the Coast, Across Castle Country, and Through Our Mountainous Heartland

The Wales Way is a new family of three national touring routes that lead you along the coast, across castle country, and through our mountainous heartland. Starts/Ends: Llandudno or Cardiff The Cambrian Way is a journey along the Ffordd Cambria The Cambrian Way Distance: 185 miles (300km) mountainous spine of Wales, running for 185 miles (300km) between Llandudno and Cardiff, winding through National Parks and big green spaces. Starts/Ends: Aberdaron or St Davids The Coastal Way travels the west coast around Ffordd yr Arfordir The Coastal Way Distance: 180 miles (290km) Cardigan Bay, a 180-mile (290km) road-trip between the sea on one side and mountains on the other. Starts/Ends: Chester or Holyhead The North Wales Way follows the main trading Ffordd y Gogledd The North Wales Way Distance: 75 miles (120km) route for 75 miles (120km) along the northern coast, taking in some of the mightiest castles, the mountains of Snowdonia, and the ancient thewalesway.com history of Anglesey. Ffordd Cambria The Cambrian Way Llandudno Holyhead 11 Anglesey Rhyl AONB Conwy 6 1. Bodnant Gardens Craft Centre 18. The Lake (scenic walk) 25 10 8 Menai 18 12 9 22 Holywell 2. Bodnant Welsh Food Centre 19. Epynt Way – Epic View Point Bridge 14 13 St Asaph 5 1 24 Bangor 7 19 2 1 3. Surf Snowdonia 20. Hay-on-Wye 3 20 15 4. Zip World Fforest 21. Cantref 21 Llanrwst Caernarfon 23 Capel Clwydian Range 5. Betws-y-Coed – Swallow Falls 22. Dan yr Ogof 17 4 and Dee Valley AONB 16 Curig 5 6. -

Penrhyn Quarry, Together with the Proposed Extension

SITE DESCRIPTION 2 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................... 2-1 LOCATION ................................................................................................................................... 2-1 SITE DESCRIPTION ....................................................................................................................... 2-1 ENVIRONMENTAL CONTEXT ......................................................................................................... 2-6 Landscape ............................................................................................................................................... 2-6 Geology ................................................................................................................................................... 2-6 Hydrology ............................................................................................................................................... 2-9 Hydrogeology........................................................................................................................................ 2-10 Sensitive Receptors ............................................................................................................................... 2-10 SITE AND PLANNING HISTORY .................................................................................................... 2-11 SITE DESCRIPTION 2 INTRODUCTION This chapter describes the -

Welsh Pony Progress

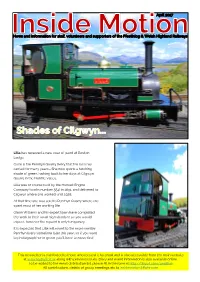

Lilla has received a new coat of paint at Boston Lodge. Gone is the Penrhyn Quarry livery that the loco has carried for many years—She now sports a fetching shade of green, harking back to her days at Cilgwyn Quarry in the Nantlle Valley. Lilla was of course built by the Hunslet Engine Company (works number 554) in 1891, and delivered to Cilgwyn where she worked until 1928. At that time she was sold to Penrhyn Quarry where she spent most of her working life. Glenn Williams and his expert team have completed the work to their usual high standard as you would expect, however the repaint is only temporary. It is expected that Lilla will revert to the more familiar Penrhyn livery sometime later this year, so if you want to photograph her in green you’ll have to move fast! This newsletter is distributed to those who request it by email and is also accessible from the main website at www.festrail.co.uk along with previous issues. Diary and event information is also available online. To be added to the email distribution list, please fill in the form at http://tinyurl.com/pmjl6ue All contributions, details of group meetings etc to [email protected] 84 volunteers were present on Megabash on 1st & 2nd The new mess room in the workshop building was April. 55 of them were based in Minffordd Yard where successfully used to provide drinks for everyone. The the objective was to tidy up and make the yard safe for area to the rear of the building had been landscaped visitors during the forthcoming Quirks & Curiosities and grass seed was scattered so that it will blend in weekend. -

Snowdonia Mountains and Coast PDF (5.69

CAMBRIAN COASTLINE LLŶN PENINSULA SNOWDONIA NATIONAL PARK 2017 Llyn Ogwen THE WAY AHEAD Things are changing in Snowdonia Mountains and Coast. We’re now home to a bucket list-full of outdoor activities like ziplining, canyoning, underground adventures and – would you believe? – inland surfing. Zip World Penrhyn Quarry Then there’s our accommodation walks and castles, vital Celtic identity scene. You can stay at hotels that and strong sense of place. There’s rare leap straight off the pages of interior quality and variety in the things to see design magazines. Or go cool camping and do here, from our charming little or glamping under our Dark Skies, railways to engaging family attractions. stargazing from around the campfire. You’ll barely scratch the surface on a Times change too – by which we mean day trip, so do yourself a favour and that travel experiences and short breaks book in for a few days or weeks. It’s throughout the year are as much part all here in this guide, together with of our portfolio as traditional summer information on the The Wales Way, a seaside holidays. collection of curated touring routes that help you make the most of your visit. Having said all that, let’s not forget the It’s the way to go. bedrock of our appeal – our rugged landscape and sweeping coastline, Snowdonia Mountains and Coast Roger Thomas, Editor Contents THE WAY 2 Travel 12 The Wales Way 30 Cycling and information mountain biking 16 All year round 4 At a glance - 32 Festivals and a snapshot of our 18 Attractions events six holiday areas and activities, adventure and 34 In the know – 6 Snowdonia relaxation, further AHEAD National Park food and information accommodation 8 Be Adventure 35 Adverts Smart – safety 26 History and advice heritage 10 Along the coast 28 Walking Join the conversation and keep in touch visitsnowdonia.info facebook.com/visitingsnowdonia Keep up to date with what’s happening and twitter.com/visit_snowdonia what’s new by joining us on our social networks. -

Cruise Wales Brochure

Cruise Wales Wales – what will you discover? Amlwch Welsh Llandudno Mountain Prestatyn Holyhead Zoo Rhyl Llangefni Beaumaris Conwy A55 Colwyn A55 Bay St Asaph Anglesey Cathedral Flint Sea Zoo Bangor Connah’s Quay Adventure Bodnant Garden Mold Parc A470 Caernarfon Snowdonia Zip World Zip World Fforest Penrhyn A5 Quarry Betws-y-coed Snowdon A494 A487 Llechwedd A5 Wrexham Slate Caverns Blaenau Erddig Welsh Highland Ffestiniog Llangollen A483 Railway A5 Pontcysyllte Aqueduct Bala Chirk Castle Pwllheli Portmeirion Italianate Village Plas yn Rhiw SNOWDONIA Harlech NATIONAL PARK Castle A470 A494 Rhaeadr Nantcol Dolgellau Waterfalls A483 A458 A487 Welshpool Powis Castle Cruise Port Motorway A489 and Garden A470 A483 Airport Trunk Road Newtown Castle Museum Llanidloes Zip Wire Zoo Abbey Aberystwyth A44 Devils Bridge Vale of Falls A483 Gardens Distillery Rheidol Railway A470 Hafod Estate Cathedral Historic House Llandrindod Caves Wells A487 Builth Wells A483 Cardigan Fishguard Fort Cilgerran Castle National Wool Fishguard Museum Llandovery A470 A40 Aberglasney Dinefwr A40 Brecon Gardens Castle A479 St Davids St Davids Cathedral National Botanic Llandeilo A470 Garden of Wales A40 BRECON BEACONS PEMBROKESHIRE COAST NATIONAL PARK A465 NATIONAL PARK Brecon A40 A483 Carreg Mountain Haverfordwest Carmarthen Cennen Abergavenny Picton A48 National Showcaves Railway Monmouth A477 Castle A4076 Castle Llanstean Centre for Wales A465 Carew Castle Castle A40 Laugharne Merthyr Big Pit Milford Haven Castle A465 Penderyn A4042 A449 Aberdulais Whisky Llanelli Falls