Using Network Analysis to Define a Tourist Destination As the Basis for a Dmo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lacus Pelso in the Roman Age the Lake Balaton and the Hydrography of the Balaton-Highland

The Lacus Pelso in the Roman Age The Lake Balaton and the Hydrography of the Balaton-Highland Anett Firnigl Corvinus University of Budapest, Department of Garden Art 29-43 Villányi Street H-1118 Hungary [email protected] Abstract. The protection of the monuments of the Roman Age is the object of the safeguarding of the highest importance, after all they could be account the first ancient civilization, which enroached consciously to the central european landscape, and basically changed that. They built cities, villages, villas, stone-houses, road network, and in several places high-leaded water-conduits, and they also felled forests, and drained moorlands for example at the Lake Balaton. The Roman villa The Roman legions appeared in the Hungarian Transdanubia at the beginning of the 1st century A.D. They organized Pannonia Province, which became a very important borderland of the Roman Empire. They built cities, villages, villas, roads, and in several places high- leaded water-conduits (so-called aquaeductus), and they also felled forests, and drained moorlands. The Production of the Roman villas gave the great mass of the agricultural and commercial background of the Province. The Roman villa was a cultivation and stock-raising adapted farm unit: it was a collection of farming- and dwelling-houses, which included the several farm buildings, the houses of the land-livings and the owner’s house often as comfortable as an urban one. Estates (named fundus) always belonged to the villas. The traces of the villa are hardly visible on the surface, but then under the surface bears not only small finds, but also the tarces of so a new agricultural technologies, which were established from the Roman Empire. -

Action Plan for Lake Balaton Region

Delivering Efficient Sustainable Tourism with low-carbon transport Innovations: Sustainable Mobility, Accessibility and Responsible Travel Action Plan for Lake Balaton Region November 2020 Map of partner area / Partner info Delivering Efficient Sustainable Tourism with low-carbon transport Innovations: S ustainable Mobility, Accessibility and Responsible Travel Map of Lake Balaton Region / Partner info Lake Balaton Development Coordination Agency is a non-profit public interest company. It was established in January 2000 by the Lake Balaton Development Council. The Agency performs professional and operative duties promoting the development of the Lake Balaton functional Region (LBR) in accordance with the scope of the competence and activities of the Council defined by the Act XXI of 1996 on Regional Development and Spatial Planning. Therefore, the basic activities of the Agency are supporting decision-making and implementation, including for example the execution of the long- term regional development concept of the LBR. The Agency also contributes to the implementation of the Lake Balaton Region Development Plan. The Agency carries out tasks related to the programming process of the Lake Balaton Region regarding to national and EU terms. It has actively participated in planning activities related to the EU programming periods. It elaborated the long-term regional development concept (2014-2030) for the Lake Balaton Region that was approved by the Council, and accepted by the Government decree no. 1821/2015 and 1861/2016. A priority task of LBDCA is managing the allocation of development funds and implementing targeted projects based on decisions of the Council. In addition, the Agency assists the planning and implementation of national sectoral strategies (e.g. -

Lake Balaton Recreational Area

Lake Balaton Recreational Area Zita Könczölné Egerszegi Environmental Director Lake Balaton Development Coordination Agency March 27, 2019. Hastings Transportation already in place: roads, railways, airports, navigation Regional airport: 20,000 passengers (2017) Navigation: 660,857 passengers (2017) Ferry: 1,000,143 passengers (2017) Motorway (M7): 25,017 vehicles/day (2016) Bicycle road: 220 km Trans-European Rail Network – south side www.google-earth.com Integrated Transport OP 2014-2020, Hungary - main objective This programme includes the main transport infrastructure investments. It focuses on further developing highways and railways across the country, improving public transport services not only in and around the capital, but also in the main cities, and on improving regional accessibility. As a result, highways will reach the borders, and more "cities with county rights" will have direct link to the trans- European transport network. Railway modernisation will continue along the main corridors across the country, with several stations to be renovated (Békéscsaba, Székesfehérvár, Szombathely). Urban transport will be further developed both in and around Budapest. Other large cities will also benefit from urban transport investments, and light train developments will link cities in the country together. Transport developments in the Lake Balaton Region from OPs - corresponding to the project objective Operational Priority and / or measure Decided Spent cost programme cost (EUR) 2015- 2018. (EUR) Economic Development of infrastructure -

Investigating Stakeholder Decision Priorities for Adapting to Climate Change in the Lake Balaton Recreational Area of Hungary

© 2008 International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) Published by the International Institute for Sustainable Development Investigating Stakeholde r Decision The International Institute for Sustainable Development contributes to sustainable Priorities for Adaptingdevelopment to Climateby advancing policy recommendations on international trade and investment, economic policy, climate change, Change in the Lake Balatonmeasurement and assessment, and natural resources management. Through the Internet, we report on international negotiations and Recreational Area ofshare Hungary knowledge gained through: collaborative projects with global partners, resulting in more rigorous research, capacity building in developing countries and better dialogue between North and South. IISD‘s vision is better living for all— Summary of Workshops sustainably; its mission is to champion innovation, enabling societies to live Held in SIÓFOK, BALATONALMÁDI sustainably. IISD is registered as a charitable organization in Canada and has 501(c)(3) status and KESZTHELY, HUNGARY, in the United States. IISD receives core During October 2007 - February 2008operating support from the Government of Canada, provided through the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA), the International Development Research Centre Livia Bizikova (IDRC) and Environment Canada; and from the Province of Manitoba. The institute receives László Pintér project funding from numerous governments inside and outside Canada, United Nations agencies, foundations and the priate -

The Development of Accommodations Around the Lake Balaton from the XVIII Century to the II World War

http://jms.sciedupress.com Journal of Management and Strategy Vol. 6, No. 2; 2015 The Development of Accommodations around the Lake Balaton from the XVIII Century to the II World War Endre György Bártfai1 & Lili Bártfai2 1 College of Commerce, Catering and Tourism, Budapest Business School, Budapest, Hungary 2 Royal Automobile Club, Hotel London, London, UK Correspondence: Endre György Bártfai, Lecturer, College of Commerce, Catering and Tourism, Budapest Business School, Budapest, Buzogány u., 1149 Hungary. E-mail: [email protected] Received: April 25, 2015 Accepted: May 13, 2015 Online Published: May 17, 2015 doi:10.5430/jms.v6n2p93 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5430/jms.v6n2p93 Abstract The study presents the history of accommodations around the Lake Balaton from the XVIII century to the II World War. After a brief description of the geology of the Lake Balaton, the writers investigate the development of the aquatic, rail and road transport; and their impact on the lake’s tourism, and divided into three sections, provides an overview of the development of lodging of this nearly two-hundred-year period. Keywords: Hungary – Lake Balaton it’s sights and role in the Hungarian tourism, development of the traffic infrastructure, accommodation development, capacities and places, the first two hundred year from the XVIII century, types of the accommodations facilities 1. Introduction … this is the kindest, most gentle and peaceful region on the Earth, indeed destined to be the relaxing resort in our overpopulated Earth” – JENŐ CHOLNOKY writes about Hungary in the introduction of his book The Geography of Hungary (1929, p. -

The First High Resolution Diatom Record from Lake Balaton, Hungary in Central Europe

Limnetica, 38(1): 417-430 (2019). DOI: 10.23818/limn.38.24 © Asociación Ibérica de Limnología, Madrid. Spain. ISSN: 0213-8409 The first high resolution diatom record from Lake Balaton, Hungary in Central Europe Krisztina Buczkó1,2,*, Éva Ács1, Katalin Báldi3, Virág Pozderka4, Mihály Braun5, Keve Tihamér Kiss1 and János Korponai6,7 1 MTA Centre for Ecological Research, Danube Research Institute, 1113 Budapest, Karolina St 29, Hungary. 2 Hungarian Natural History Museum, Department of Botany, 1088 Budapest, Baross St 13, Hungary. 3 Eötvös Loránd University, Department of Physical & Applied Geology, 1117 Budapest, Pázmány Péter St 1/c, Budapest, Hungary. 4 Eötvös Loránd University, Doctoral School of Environmental Sciences, 1117 Budapest, Pázmány Péter St 1/c, Budapest, Hungary. 5 Isotope Climatology and Environmental Research Centre (ICER), Institute for Nuclear Research, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 4026 Debrecen, Bem Square 18/C, Hungary. 6 Department of Environmental Sciences, Sapientia Hungarian University of Transylvania, 400193 Cluj-Napoca, Calea Turzii str. 4., Romania. 7 MTA - PE Limnoecology Research Group, 8200 Veszprém, Wartha Vince St 1. Hungary. * Corresponding author: [email protected] Received: 13/04/18 Accepted: 19/11/18 ABSTRACT The first high resolution diatom record from Lake Balaton, Hungary in Central Europe A high-resolution diatom record of the last 7500 years of Lake Balaton, a large, shallow calcareous lake in Central Europe is presented here. Diatom analyses were carried out on a 112 cm long core obtained from the Siófok Basin (eastern part of the lake) combined with loss-on-ignition, geochemical measurements and grain-size analysis. Altogether 140 diatom taxa were distinguished in this study; Amphora pediculus, Cocconeis neothumensis, Fragilaria brevistriata and Karayevia clevei were frequent and ubiquitous members of diatom assemblages. -

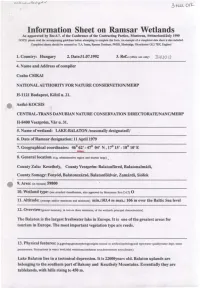

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands As Apporoved by Rec.4.7

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands As apporoved by Rec.4.7. of the Conference of the Contracting Parties, Montreux, Switzerland/July 1990 NOTE please read the accompanying guidelines before attempting to complete this form. An example of a completed data sheet is also included. Completed sheets should be returned to: TA Jones, Ramsar Database, IWRB, Slimbridge, Glouchester GL2 7BX, England 1. Country: Hungary 2. Date:31.07.1992 3. Ref.: (office use only) 3 NU O 12 4. Name and Address of compiler Csaba CSIKAI NATIONAL AUTHORITY FOR NATURE CONSERVETION/MERP H-1121 Budapest, Kolt6 u . 21. Aniko KOCSIS CENTRAL-TRANS DANUBIAN NATURE CONSERVATION DIRECTORATE/NANC/MERP H-8400 Veszprem, Var u . 31. 5. Name of wetland : LAKE-BALATON /seasonally designated!/ 6. Date of Ramsar designation : 11 April 1979 7. Geographical coordinates : 46° 62' - 470 04' N ,17° 15' -18° 10' E WWA 8. General location: (e.g. administrative region and nearest large) - County Zala : Keszthely, County Veszprem: Balatonfared, Balatonalmadi, County Somogy: Fonyod, Balatonszarzo, Balatonfoldvar, Zamardi, Siofok ift 9. Area: (in hectars) 59800 10. Wetland type: (sec attached classification, also approved by Montreaux Rec .C.4,7) 0 11. Altitude: (average and/or maximum and minimum) min.:103,4 m max.: 106 m over the Baltic Sea level 12. Overview:(genral summary, in two or three sentences, of the wetlands principal characteristics) The Balaton is the largest freshwater lake in Europe . It is one of the greatest areas for tourism in Europe . The most important vegetation type are reeds . 13. Physical features : (e.g.geologygeomorphology;origins-natural or artifcal ;hydrology;soit type;water quality,-water dept ; water permanence ; fluctuations in water level ;tidal variations;catchment area;downstream area;climate) Lake Balaton lies in a tectonical depression . -

Balaton Guest, Region of Unrivalled Beauty

DearWelcome to the Balaton Guest, region of unrivalled beauty. The Balaton region is one of Hungary’s most popular destinations; where you can trek in the beautiful National Park, go hiking up the mountains and hills that offer outstanding panoramas, or Balaton where you can rest your weary body and soul at any of the numerous wellness and spa hotels. You can indulge in leisurely rejuvenation and relaxation, sail across the calm waters of the lake or take a tranquil cruise. Your children can splash away in the shallow, silky water or take part in more active Table of contents recreational activities. You can try the fragrant wines of the region and enjoy tasty dishes that are Water Tourism 2 renowned throughout Europe, whilst experiencing the friendly, local hospitality. Nature 6 Europe’s largest thermal water lake; a golf course with one of the most magnificent views and the first written historical memento of the Hungarian language held in an ancient abbey, can all be Active Tourism 10 found in the Balaton region. Cure and Wellness 16 This brochure will guide you through the most beautiful natural sites of the Balaton, offer optional Wine and Gastronomy 28 alternatives for active and leisurely recreation and provide essential information and suggestions for Our Cultural Treasures 34 an unforgettable, fun-filled vacation in our region. Be our guest and come along and enjoy yourself with the countless experiences we offer. Events Highlights 40 Accommodations 42 Service Providers 45 Balaton –Sailboats conquer Lake Balaton’s water daily, defying the winds „…sailing…” that sometimes confounds even the experienced who live near its shores. -

DATA on the PERIPHYTON of the BALATON Abstract Introduction

Acta Biologica Szeged. 25 (3—4), pp. 29—34 (1979) DATA ON THE PERIPHYTON OF THE BALATON G. UHERKOVICH (Received February 20, 1979) Abstract The author has processed the periphyton samples of reeds, bulrushes and of the hair-weed vegetation at five different points of the northern side of Lake Balaton. In one of the sample series the periphyton associations of the Paloznak-bay in the vicinity of Balatonfiired are discussed in this paper. It ascertains that there are differences in the composition of the periphyton both accord- ing to the undergrowth and to the levels of depth. The periphyton associations within the reeds and at their fringe towards the water differ from one another in the same way. He found particularly in the periphyton associations in the interior of reed banks numerous algae that are otherwise characteristic of the transitory bogs. The separation of types will only be possible after elaborating further partial results in the relation of the periphyton of the Balaton. Introduction From among the algal organizations of the Balaton those to be found in the "plankton" have been studied the most exhaustively. About the algae of the "benthos" we have less knowledge. (For explaining the quotation-marks = the Balaton is a shallow lake, its water is stirred till the bottom by strong enough waves. The organisms floating in it and those living fallen down to the surface of the sedi- ment may esasily change their place. There are, therefore, in the plankton some organisms stirred up from the bottom and this is true just the other way round, as well.) The least investigated and known biotope of the water of the Balaton is the sometimes considerable macrophyton zone of the inshore fringe (reeds, walrushes, etc.), the coating, living on the stems of plants, thus also the periphyton formed by the algae. -

Customer Involvement in Sustainable Tourism Planning at Lake Balaton, Hungary—Analysis of the Consumer Preferences of the Active Cycling Tourists

sustainability Article Customer Involvement in Sustainable Tourism Planning at Lake Balaton, Hungary—Analysis of the Consumer Preferences of the Active Cycling Tourists Katalin L˝orincz 1, Zsuzsanna Banász 2 and János Csapó 3,* 1 Department of Tourism, University of Pannonia, Egyetem str. 10, H-8200 Veszprém, Hungary; [email protected] 2 Department of Quantitative Methods, University of Pannonia, Egyetem str. 10, H-8200 Veszprém, Hungary; [email protected] 3 Institute of Marketing and Tourism, Faculty of Business and Economics, University of Pécs, Rákóczi str. 80, H-7622 Pécs, Hungary * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 14 May 2020; Accepted: 21 June 2020; Published: 24 June 2020 Abstract: This study uses an innovative tourism product development approach, based on co-creation or customer involvement, related to Lake Balaton, a mass tourism-based destination in Hungary, from the point of view of the market segment of active cycling tourists. The investigation of opportunities for the development of cycling tourism first of all relies on the new approach of attraction and product development around the destination, in which it is important to take into consideration the consumer preferences of the most important related group of tourists—active cycling tourists. The sustainable approach of tourism product development also provides an opportunity to decrease the spatial and temporal concentration of tourism, which is largely concentrated on the summertime season. The aim of this study is to explore aspects of the customers’ demand for tourism development in terms of cycling tourism with the help of primary data collection, in order to provide adequate directions for sustainable tourism development in the destination. -

Not for Quotation Without Permission of the Author

NOT FOR QUOTATION WITHOUT PERMISSION OF THE AUTHOR LAKE BALATON EUTROPHICATION STUDY: Present Status and Future Program Gerrit van Straten ~Sszl6Somly6dy December 1980 WP-80-187 Working Papers are interim reports on work of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis and have received only limited review. Views or opinions expressed herein do not necessarily repre- sent those of the Institute or of its National Member Organizations. INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR APPLIED SYSTEMS ANALYSIS A-2361 Laxenburg, Austria THE AUTHORS G. VAN STRATEN is with the Department of Chemical Technoiogy, Twente University of Technology, Enschede, The Netherlands. Formerly, he was a research scholar and leader of the Lake Balaton Case Study at IIASA from April 1978-December 1979. L. Somiy6dy is on leave from the Research Center for Water Resources Development (VITURI), Budapest, Hungary. He is a research scholar and the present leader of the Case Study at IIASA from February, 1980. PREFACE The deterioration of lakes' water quhlity due to artificiai eutrophication is a typical symptom of our civilization. To stop this process and to improve the waterquality in anec~nomical way requires a systematic and coordinated anaiysis of many disci- plines. The recognition of this fact related to Lake Balaton, one of the primary touristic resorts of Hungary and the largest shallow lake in Middle-Europe, initiated IIASA and the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in 1978 to establish a cooperative research on the development of ecological models and their practical application to the lake. In addition, it was felt that not onlya contribution can be given to solve the problem of theLake Balaton region but the methodologies developed can be generalized for other shallow lakes which represent, in general, a less studies field compared to deep lakes. -

Travel Guide in Veszprém County Hungary on 11.A’S Recommendation Imre BRODY Grammar School

BRODY IMRE SECONDARY GRAMMAR SCHOOL 4. BRODY STREET AJKA 8400 HUNGARY Travel Guide in Veszprém County Hungary on 11.A’s recommendation Imre BRODY Grammar School Places to visitvisit: Badacsony, Balatonederics, Balatonfüred, Devecser ,Keszthely, Kislıd, Kup, Magyarpolány, Sümeg, Tapolca, Tihany, Vörösberény 10th June 2010, Ajka Badacsony by Márton Makkay Badacsony lies in the north of Lake Balaton. Four towns make up this region: Badacsonylábdihegy, Badacsonyörs, Badacsonytördemic and Badacsonytomaj. But when Hungarians say Badacsony, they usually mean the little resort at the Badacsony train station, near the ferry pier southwest of Badacsonytomaj. Badacsony is thrice-blessed. Not only does it have the lake for swimming and the mountains for wonderful walks and hikes, but it has produced wine - lots of it - since the Middle Ages. The most fa- mous wines are Szürkebarát and Kéknyelvő. On the mountain of Badacsony we can see some basalt organs which also attract a lot of tourists. I have a personal attachment to Badacsony. From 1995 to 2009 my family had a summer house in Badacsonytomaj. We spent there a lot of memorable moments. Unfortunately last year we had to sell this house. However, this summer I will visit Badacsonytomaj again because it is a great place to relax and I can recommend it to every- body who want to spend a few calm days here with his/her family or friends. Brody Imre Secondary Grammar School 4. Brody Street Ajka 8400 Hungary Balatonederics by Anett Merse Balatonederics is situated on the North side of Lake Balaton near Keszthely. The village is famous for its well-known museum called 'Africa Museum'.