Currentissueofjournal.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Invitation for Bids for the Work of " Restoration And

BIDDING DOCUMENTS FOR PROCUREMENT OF WORKS IFB No. 01/AP/VMRDA/APDRP/Visakhapatnam/2019-20 Name of Work: Restoration & Redevelopment of 380 Acres Kailasagiri Hill Top park at Visakhapatnam. STEP Activity No. IN-PIU-VMRDA-103847-CW-RFB Project: Andhra Pradesh Disaster Recovery Project. Bid Inviting Authority: Metropolitan Commissioner, VMRDA, Udyog Bhavan, Siripuram Jn.,Visakhapatnam-530003. Country : India Metropolitan Commissioner, VMRDA, 9th Floor, Udyog Bhavan, SiripuramJn.,Visakhapatnam-530003. Telephone:- 0891-2754133/34, 2755155, 9866076925, 7702333584 Email :- [email protected], [email protected], 2 INVITATION FOR BID (IFB) 3 GOVERNMENT OF ANDHARA PRADESH ANDHRA PRADESH DISASTER RECOVERY PROJECT IFB NO: 01/ AP/VMRDA/APDRP/Visakhapatnam/2019-20 NATIONAL COMPETITIVE BIDDING (Two-Envelope Bidding Process with e-Procurement) (FOR ITEM RATE/ADMEASUREMENT CONTRACTS IN CIVIL WORKS) NAME OF WORK : RESTORATION & RE-DEVELOPMENT OF 380 ACRES KAILASAGIRI HILL TOP PARK AT VISAKHAPATNAM DATE OF ISSUE OF IFB : 30-09-2019 AVAILIBILTY OF BIDDING : FROM DATE : 03-10-2019 TIME11.00 HOURS DOCUMENT ON-LINE : TO DATE : 02-11-2019 TIME 15.00 HOURS TIME AND DATE OF : DATE :16-10-2019 TIME: 11.30 HOURS PREBID CONFERENCE LAST DATE AND TIME FOR : DATE :02-11-2019 TIME: 15.30 HOURS RECEIPT OF BIDS ON-LINE LAST DATE FOR SUBMITTING HARD : DATE :02-11-2019 TIME: 15.30 HOURS COPIES BY THE BIDDERS TIME AND DATE OF DATE :02-11-2019 TIME: 16.00 HOURS OPENING OF PART 1 OF : BIDS ONLINE [TECHNICAL QUALIFICATION PART] TIME AND DATE OF OPENING OF PART 2 OF BIDS ONLINE -

The Visakhapatnam Chemical Disaster Arpita Pattnaik & Ketaki Vatsa

I S S N : 2 5 8 2 - 2 9 4 2 LEX FORTI L E G A L J O U R N A L V O L - I I S S U E - V J U N E 2 0 2 0 I S S N : 2 5 8 2 - 2 9 4 2 DISCLAIMER N O P A R T O F T H I S P U B L I C A T I O N M A Y B E R E P R O D U C E D O R C O P I E D I N A N Y F O R M B Y A N Y M E A N S W I T H O U T P R I O R W R I T T E N P E R M I S S I O N O F E D I T O R - I N - C H I E F O F L E X F O R T I L E G A L J O U R N A L . T H E E D I T O R I A L T E A M O F L E X F O R T I L E G A L J O U R N A L H O L D S T H E C O P Y R I G H T T O A L L A R T I C L E S C O N T R I B U T E D T O T H I S P U B L I C A T I O N . -

District Disaster Management Action Plan 2017

PUDUCHERY DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT ACTION PLAN 2017 STATE LEVEL EMERGENCY OPERATION CENTER (SLEOC) TOLL FREE NUMBER 1077 / 1070 Off: 2253407 / Fax: 2253408 VSAT - HUB PHONE NO : 81627 e-Mail SLEOC : [email protected] / [email protected] District Collector : [email protected] Collectorate e-Mail : [email protected] NATIONAL DISASTER MANAGEMENT AUTHORITY (NDMA) HELPLINE NUMBER 011-1078 Control Room: 011-26701728 Fax: 011-26701729 E-mail: [email protected] Postal Address: NDMA Bhawan, A-1, Safdarjung Enclave, New Delhi – 110029 Telephone : 011-26701700 Contents 1 CHAPTER..............................................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................1 1.1 Objectives of this Action Plan......................................................................................1 2 CHAPTER..............................................................................................................................3 2.1 LOCATION....................................................................................................................3 2.2 CLIMATE ......................................................................................................................3 2.3 TOPOGRAPHY..............................................................................................................3 2.3.1 Puducherry Region ..............................................................................................3 -

Current Affairs May 2020

Current Affairs – May 2020 Current Affairs ─ May 2020 This is a guide to provide you a precise summary and a huge collection of Multiple Choice Questions (MCQs) covering national and international current affairs for the month of May 2020. This guide will help you in preparing for Indian competitive examinations like Bank PO, Banking, Railway, IAS, PCS, UPSC, CAT, GATE, CDS, NDA, MCA, MBA, Engineering, IBPS, Clerical Gradeand Officer Grade, etc. Audience Aspirants who are preparing for different competitive exams like Bank PO, Banking, Railway, IAS, PCS, UPSC, CAT, GATE, CDS, NDA, MCA, MBA, Engineering, IBPS, Clerical Grade, Officer Grade, etc. Even though you are not preparing for any exams but are willing to have news encapsulated in a roll, which you can walk through within 30 minutes, then we have put all the major points for the whole month in a precise and interesting way. Copyright and Disclaimer Copyright 2020 by Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. All the content and graphics published in this e-book are the property of Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. The user of this e-book is prohibited to reuse, retain, copy, distribute or republish any contents or a part of contents of this e-book in any manner without written consent of the publisher. We strive to update the contents of our website and tutorials as timely and as precisely as possible, however, the contents may contain inaccuracies or errors. Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. provides no guarantee regarding the accuracy, timeliness or completeness of our website or its contents including this tutorial. -

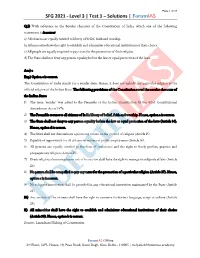

SFG 2021 - Level 3 | Test 1 – Solutions | Forumias

Page 1 of 47 SFG 2021 - Level 3 | Test 1 – Solutions | ForumIAS Q.1) With reference to the Secular character of the Constitution of India, which one of the following statements is incorrect? a) All citizens are equally entitled to liberty of belief, faith and worship. b) All minorities have the right to establish and administer educational institutions of their choice. c) All people are equally required to pay taxes for the promotion of their religion. d) The State shall not deny any person equality before the law or equal protection of the laws. Ans) c Exp) Option c is correct. The Constitution of India stands for a secular state. Hence, it does not uphold any particular religion as the official religion of the Indian State. The following provisions of the Constitution reveal the secular character of the Indian State: 1) The term ‘secular’ was added to the Preamble of the Indian Constitution by the 42nd Constitutional Amendment Act of 1976. 2) The Preamble secures to all citizens of India liberty of belief, faith and worship. Hence, option a is correct. 3) The State shall not deny to any person equality before the law or equal protection of the laws (Article 14). Hence, option d is correct. 4) The State shall not discriminate against any citizen on the ground of religion (Article 15). 5) Equality of opportunity for all citizens in matters of public employment (Article 16). 6) All persons are equally entitled to freedom of conscience and the right to freely profess, practice and propagate any religion (Article 25). -

Market Assessment of Solar Water Heating Systems in Five Potential States/Ncr Region

MARKET ASSESSMENT OF SOLAR WATER HEATING SYSTEMS IN FIVE POTENTIAL STATES/NCR REGION Final Report Submitted to Project Management Unit UNDP/GEF Assisted Global Solar Water Heating Project Ministry of New and Renewable Energy Government of India 10 February, 2011 Submitted by: Greentech Knowledge Solutions (P) Ltd. New Delhi -110078 (India) Website: www.greentechsolution.co.in Final Report: Market Assessment of Solar Water Heating Systems in Five Potential States / NCR Region PROJECT TEAM Core Team Dr Sameer Maithel, Greentech Knowledge Solutions (GKS), New Delhi Mr Shailesh Modi, Fourth Vision Consultants (FVC), Ahmedabad Mr Minhaj Ameen, EvalueS, Auroville Mr Prashant Bhanware, GKS, New Delhi Mr Rahul Rai, GKS, New Delhi Regional Teams North Dr Sameer Maithel, Mr Prashant Bhanware, Mr Gaurav Malhotara & Mr Rahul Rai, GKS, New Delhi Mr Richard Sequeira, Solenge India, Gurgaon South Mr Minhaj Ameen, Mr Arijit Mitra, Mr Erik Conesa, EvalueS, Auroville West Mr Shailesh Modi, Mr Vimal Suthar, Mr Mihir Vyas, Mr Vipin Thakur, Prof. Mahesh Shelar, Mr Haresh Patel, FVC, Ahmedabad Greentech Knowledge Solutions ii Final Report: Market Assessment of Solar Water Heating Systems in Five Potential States / NCR Region ACKNOWLEDGEMNETS The project team would like to sincerely thank Dr Bibek Bandyopadhyay, Advisor and Head, MNRE and Mr Ajit Gupta, National Project Manager, UNDP/GEF Global Solar Water Heating Project for their guidance during the entire duration of the project. Periodic review meetings organized by the Project Management Unit helped immensely in shaping the study. We are also grateful to the members of the Project Executive Committee as well as participants of the stakeholders‟ consultation workshop for their suggestions and inputs. -

Proposed Project Location – Key Map 0 0 82 30’ 820 15’ 820 20’ 82 25’

F1 - 26 Proposed LNG FSRU Terminal Annexure - 1 Proposed Project Location – Key Map 0 0 82 30’ 0 0 82 25’ 82 15’ 82 20’ 0 17 05’ F1 Proposed Widening and - Deepening of entry channel 27 Proposed Subsea pipeline 170 Proposed Onshore Island Jetty Facility 00’ Proposed 600 mɸ Turning Circle Annexure - 0 16 2 55’ Preliminary Layout of Proposed Project F1 - 28 (A) Identified location for Offshore Facility (Island Jetty & FSRU) Annexure - 3 (B) Identified location for Onshore Facility (landfall Point) Project Site Photographs APPENDEX I (Revised as per MoEF Notification S.O.3067(E) dt. 01.12.2009) (See paragraph – 6) FORM 1 (I) Basic Information Sr. Item Details No. 1. Name of the Project/s Development of offshore LNG FSRU Facility at Kakinada Deep Water Port 2. S.No. in the schedule 7(e) 3. Proposed The project will be designed for 6.5 Million Ton capacity/area/length/tonnage to be Per Annum (MTPA) LNG throughput (Equivalent handled/command area/lease to Approx. 26.9 MMSCMD Natural Gas flow area/number of wells to be drilled rate) 4. New/Expansion/Modernization Expansion 5. Existing Capacity/Area etc. The existing Kakinada Deep Water Port handled 10.8 Million Metric ton Multiple Cargo during 2010-’11 6. Category of Project i.e., 'A' or 'B' ‘A’ 7. Does it attract the general Not applicable, since proposed project falls in ‘A’ condition? If yes, category Please specify. 8. Does it attract the specific -No- condition? If yes, Please specify. 9. Location Kakinada Deep Water Port, Kakinada, East Godavari District, Andhra Pradesh (Annexure- 1). -

Visakhapatnam-Chennai Industrial Corridor Development Program-Project 1

Initial Environmental Examination _________________________________________________________________________ Project Number: 48434-003 Grant Number: 0495-IND October 2018 IND: Visakhapatnam-Chennai Industrial Corridor Development Program-Project 1 Mudasarlova Lake Development Project Prepared by Greater Visakhapatnam Municipal Corporation, Government of Andhra Pradesh for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 11 October 2018) Currency Unit = Indian rupees (₹) ₹1.00 = $0.0135 $1.00 = ₹73.785 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank ASI – Archeological Survey of India CAPP – community awareness and public participation CFE – consent for establishment CFO – consent for operation GVMC – Greater Visakhapatnam Municipal Corporation DoF – Department of Forest DoL – Department of Labour EAC – Expert Appraisal Committee EARF – environmental assessment and review framework EIA – environmental impact assessment EMP – environmental management plan GRM – grievance redress mechanism IEE – initial environmental examination LARRA – land acquisition, rehabilitation and resettlement authority MFF – multi-tranche financing facility MoEFCC – Ministry of Environment and Forest, Climate Change NGO – non-governmental organization NGT – National Green Tribunal GVMC – Greater Visakhapatnam Municipal Corporation PMC – project management consultancy PMU – program management unit PPTA – project preparatory technical assistance ROW – right of way SPS – Safeguard Policy Statement TOR – terms of reference UGR – underground service reservoir WTP – water treatment plant WEIGHTS AND MEASURES m3 – cubic meter m3/h – cubic meter per hour cm – centimeter dBA – decibel audible °C – degree Celsius ha – hectare km – kilometer m – meter mm – millimeter mm/hr – millimeters per hour km2 – square kilometer m2 – square meter NOTES (i) The fiscal year (FY) of the Government of India and its agencies ends on 31 March. (ii) In this report, "$" refers to United States dollars. This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. -

Vizag Gas Leak Puller Thumbnail- How to Make Notes While Taking Youtube Classes- 2021

Vizag Gas LeaK Puller Thumbnail- How to make notes while taking youtube classes- 2021 Why Vedantu Pro is the Best? Live Interactive Classes Test Series & Analysis ● LIVE & Interactive Teaching Style ● Exclusive Tests To Enable Practical ● Fun Visualizations, Quizzes & Application ● Mock & Subject Wise Tests, Previous Leaderboards Year Tests ● Daily Classes on patented WAVE platform ● Result Analysis To Ensure Thorough ● Dual Teacher Model For Personal Preparation Attention Assignments & Notes ● Regular Assignments To Ensure Progress ● Replays, Class Notes & Study Materials Available 24*7 ● Important Textbook Solutions What is Included in Vedantu Pro? ● Full syllabus Structured Long Term Course ● 20+ Teachers with 5+ years of experience ● Tests & Assignments with 10,000+ questions ● Option to Learn in English or Hindi ● LIVE chapter wise course for revision ● 4000+ Hours of LIVE Online Teaching ● Crash Course and Test Series before Exam Vedantu JEE 2021 PRO Subscription 1 Month: ₹7,500 - ₹3,750/- 3 Months: ₹21,000 - ₹11,000/- 6 Months: ₹39,000 - ₹29,000/- *Link Available in Description Apply Coupon Code: HMPRO Vedantu JEE 2022 PRO Subscription 1 Month: ₹5,000 - ₹2,500/- 3 Months: ₹13,500 - ₹6,750/- 6 Months: ₹24,000 - ₹12,000/- 12 Months: ₹42,000 - ₹30,000/- *Link Available in Description Apply Coupon Code: HMPRO Vedantu PRO-LITE FOR JEE DROPPERS 1 Month: ₹9,000 - ₹4,500/- 3 Months: ₹25,500 - ₹15,000/- 6 Months: ₹51,000 - ₹41,000/- *Link Available in Description Apply Coupon Code: HMPRO How to Avail The Vedantu Pro Subscription 1 2 3 4 -

Visakhapatnam Gas Leak

The Big Picture: Visakhapatnam Gas Leak drishtiias.com/printpdf/the-big-picture-visakhapatnam-gas-leak Watch Video At: https://youtu.be/zOc0JZFGbpU A major leak from a polymer plant LG Polymers near Visakhapatnam impacted villages in a five-km radius, leaving at least 9 people dead and thousands of citizens suffering from breathlessness and other problems in an early morning mishap that raised fears of a serious industrial disaster. The leak occurred early morning on May 7, 2020, at a private plastic making plant owned by LG Polymers Pvt Ltd, a part of South Korean conglomerate LG Corp. The chemical plant was closed due to the lockdown for a long time and attempts were made to restart the operation. During this course, some chemical activity got started in the tank and a large amount of Styrene gas was leaked in surroundings. The exact cause of this incident is still unknown and further investigations are going on. 1/5 Fire engines, the police, and ambulances reached the area to control the situation.The trained chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear (CBRN) defense team of NDRF rushed to the spot and evacuated 1,200 families to safe locations, and about 400 people were admitted to the hospital. The National Human Rights Commission of India issued a notice to the Andhra Pradesh government and the Centre following the leakage of poisonous gas. Styrene and Its Impact Styrene is a flammable liquid that is used in the manufacturing of polystyrene plastics, fiberglass, rubber, and latex. It is also found in vehicle exhaust, cigarette smoke, and in natural foods like fruits and vegetables. -

STYRENE GAS LEAK “Styrene Being a Toxic Chemical, It Should Be Handled by Observing All Safety Measures” - R

STYRENE GAS LEAK “Styrene being a toxic chemical, it should be handled by observing all safety measures” - R. Rajasekharan Nair INTRODUCTION Today, all our efforts are diverted to contain the spread of COVID-19. To fight against COVID-19 Pandemic, our country has resorted to the lockdown procedures which began on 25th March, 2020. The COVID-19 Lockdown period was extended thrice and now we are in the fourth phase of lockdown, which will end on the 31st May, 2020. During the lockdown period, almost all the economic activities of the country were stalled. However, in phase 3 of the lockdown, some relaxations were given to resume selected production activities especially in Micro, Small and Medium Establishments (MSME) units. The LG Polymers India Private Limited (LGPI), Visakhapatnam, is one among the few units who wanted to resume the production, after a gap of 40 days COVID-19 induced lockdown. Accordingly, the plant started its maintenance activities and during this process, the Styrene gas leaked from the plant in the early hours of 7th May, 2020. The styrene vapour spread over R.R. Venkatapuram and four other villages of Visakhapatnam in a radius of 1.5 to 3 KM. After inhaling the styrene gas, 12 persons died and more than 300 were hospitalised, out of which the condition of 20 were critical, requiring ventilator support. Due to this tragedy, more than 2000 residents had to be evacuated from areas in the vicinity of the LGPI. Incidentally, no employee of LGPI was injured in this accident. Since no factory employee was injured, probably, it may not be treated as an industrial disaster under the purview of the Factories Act of India, 1948. -

Tragedy in Red Zone Area Leaves Doctors Worried Why Did Alarms Not

Follow us on: RNI No. TELENG/2018/76469 @TheDailyPioneer facebook.com/dailypioneer Established 1864 Published From ANALYSIS 7 MONEY 8 SPORTS 11 VIJAYAWADA DELHI LUCKNOW B SMES MUST ENHANCE RESOURCE ‘EXODUS OF MIGRANT WORKERS TO I ALSO FEEL PRESSURE LIKE HOPAL RAIPUR CHANDIGARH EFFICIENCY, PROFITABILITY IMPACT INDUSTRY, FARM SECTORS' EVERYONE ELSE: DHONI BHUBANESWAR RANCHI DEHRADUN HYDERABAD *Late City Vol. 2 Issue 185 VIJAYAWADA, FRIDAY MAY 8, 2020; PAGES 12 `3 *Air Surcharge Extra if Applicable SAM TAKES ACTING LESSONS FROM HELEN MIRREN { Page 12 } www.dailypioneer.com # VizagGasLeak Major gas leak at LG polymers leaves 11 dead 20 critical, 360 hospitalised in port city President of India @rashtrapatibhvn The 11 victims Spoke to officials of MHA and A Chandramouli (19) NDMA regarding the situation in Kundana Sreya (6) Visakhapatnam, which is being N Greeshma (9) monitored closely. I pray for everyone’s safety and well-being Appala Narasamma (45) Children who fell victim to the gas leak are shifted to hospital in an ambulance in Vizag city on Thursday. in Visakhapatnam. Ch Ganga Raju (48) B Narayanamma (35) No permission given Krishna Murthy (72) P Varalakshmi (38) to LG Polymers: DIC N Nani (40) P Sankara Rao (40) PNS n VISAKHAPATNAM Narendra Modi V Nookaraju (50) The general manager of District @narendramodi Industries Centre on Thursday Spoke to officials of MHA and WHAT IS STYRENE? stated that no permission was HOW POISONOUS IS IT accorded to LG Polymers to NDMA regarding the situation in Styrene is primarily a Depends on the exposure time. Acute resume production, which was Visakhapatnam, which is being synthetic chemical.