Tobacco Minimum Pricing Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Overview of Tax Legislation and Rates 19 March 2014

Overview of Tax Legislation and Rates 19 March 2014 Official versions of this document are printed on 100% recycled paper. When you have finished with it please recycle it again. If using an electronic version of the document, please consider the environment and only print the pages which you need and recycle them when you have finished. Contents Introduction Chapter 1 – Finance Bill 2014 Chapter 2 – Future Tax Changes Annex A – Tax Information and Impact Notes (TIINs) Annex B – Rates and Allowances 1 Introduction This document sets out the detail of each tax policy measure announced at Budget 2014. It is intended for tax practitioners and others with an interest in tax policy changes, especially those who will be involved in consultations both on the policy and on draft legislation. The information is set out as follows: Chapter 1 provides detail on all tax measures to be legislated in Finance Bill 2014, or that will otherwise come into effect in 2014-15. This includes confirmation of previously announced policy changes and explains where changes, if any, have been made following consultation on the draft legislation. It also sets out new measures announced at Budget 2014. Chapter 2 provides details of proposed tax changes announced at Budget 2014 to be legislated in Finance Bill 2015, other future finance bills, programme bills or secondary legislation. Annex A includes all Tax Information and Impact Notes published at Budget 2014. Annex B provides tables of tax rates and allowances. Finance Bill 2014 will be published on 27 March 2014. 2 1 Finance Bill 2014 1.1 This chapter summarises tax changes to be legislated in Finance Bill 2014 or other legislation, including secondary legislation having effect in 2014-15. -

TAC0087 Page 1 of 7 Written Evidence Submitted by Action On

TAC0087 Written evidence submitted by Action on Smoking and Health Introduction 1. This consultation response has been written by Deborah Arnott and Robbie Titmarsh from Action on Smoking and Health (ASH) and Dr J Robert Branston, Senior Lecturer in Business Economics, University of Bath, on behalf of ASH. 2. ASH is a public health charity set up by the Royal College of Physicians in 1971 to advocate for policy measures to reduce the harm caused by tobacco. ASH receives funding for its full programme of work from the British Heart Foundation and Cancer Research UK. ASH has also received project funding from the Department of Health and Social Care to support delivery of the Tobacco Control Plan for England. ASH does not have any direct or indirect links to, or receive funding from, the tobacco industry. 3. ASH is responding to this inquiry because of the substantial benefits increasing tobacco taxation would deliver in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Increased tobacco taxation would strengthen the UK’s tax base and support the delivery of government objectives, including those for England to be smoke-free by 2030;1 to ‘level up’ society;2 and to increase disability-free life years significantly,3 while reducing inequalities. 4. The effects of COVID-19 have not been felt equally across society, with those living in the most deprived areas more than twice as likely to die from the virus as those living in the least deprived areas.4 People from the lowest socio-economic groups are also those who disproportionately bear the burden of harm caused by smoking. -

All 23 Taxes.Pdf

Air passenger duty 1 Alcohol duty 2 Apprenticeship levy 3 Bank corporation tax surcharge 4 Bank levy 5 Business rates 6 Capital gains tax 7 Climate change levy 8 Corporation tax 9 Council tax 10 Fuel duty 11 Income tax 13 Inheritance tax 15 Insurance premium tax 16 National insurance 17 Petroleum revenue tax 19 Soft drink industry levy 20 Stamp duty land tax 21 Stamp duty on shares 22 Tobacco duty 23 TV licence fee 24 Value added tax 25 Vehicle excise duty 26 AIR PASSENGER DUTY What is it? Air passenger duty (APD) is a levy paid by passengers to depart from UK (and Isle of Man) airports on most aircraft. Onward-bound passengers on connecting flights are not liable, nor those on aircraft weighing under 10 tonnes or with fewer than 20 seats. It was introduced in 1994 at a rate of £5 per passenger to EEA destinations, and £10 to non-EEA destinations. In 2001 a higher rate for non-economy class seats was introduced. In 2009 EEA and non-EEA bands were replaced with four distance bands (measured from the destination’s capital city to London, not the actual flight distance) around thresholds of 2,000, 4,000 and 6,000 miles. In 2015 the highest two bands were abolished, leaving only two remaining: band A up to 2,000 miles and band B over 2,000 miles. For each band there is a reduced rate (for the lowest class seats), a standard rate and a higher rate (for seats in aircraft of over 20 tonnes equipped for fewer than 19 passengers). -

Country and Regional Public Sector Finances: Methodology Guide

Country and regional public sector finances: methodology guide A guide to the methodologies used to produce the experimental country and regional public sector finances statistics. Contact: Release date: Next release: Oliver Mann 21 May 2021 To be announced [email protected]. uk +44 (0)1633 456599 Table of contents 1. Introduction 2. Experimental Statistics 3. Public sector and public sector finances statistics 4. Devolution 5. Country and regional public sector finances apportionment methods 6. Income Tax 7. National Insurance Contributions 8. Corporation Tax (onshore) 9. Corporation Tax (offshore) and Petroleum Revenue Tax 10. Value Added Tax 11. Capital Gains Tax 12. Fuel Duties 13. Stamp Tax on shares 14. Tobacco Duties 15. Beer Duties 16. Cider Duties 17. Wine Duties Page 1 of 41 18. Spirits Duty 19. Vehicle Excise Duty 20. Air Passenger Duty 21. Insurance Premium Tax 22. Climate Change Levy 23. Environmental levies 24. Betting and gaming duties 25. Landfill Tax, Scottish Landfill Tax and Landfill Disposals Tax 26. Aggregates Levy 27. Bank Levy 28. Stamp Duty Land Tax, Land and Buildings Transaction Tax, and Land Transaction Tax 29. Inheritance Tax 30. Council Tax and Northern Ireland District Domestic Rates 31. Non-domestic Rates and Northern Ireland Regional Domestic Rates 32. Gross operating surplus 33. Interest and dividends 34. Rent and other current transfers 35. Other taxes 36. Expenditure methodology 37. Annex A : Main terms Page 2 of 41 1 . Introduction Statistics on public finances, such as public sector revenue, expenditure and debt, are used by the government, media and wider user community to monitor progress against fiscal targets. -

The Effects of Tobacco Duty on Households Across the Income Distribution the Effects of Tobacco Duty on Households Across the Income Distribution

The effects of tobacco duty on households across the income distribution The effects of tobacco duty on households across the income distribution Introduction October 2017 The effects of tobacco duty on households across the income distribution Tobacco duty in the UK is exceptionally high compared to most other EU countries.1 Due to the large specific duty component (£207.99 per 1,000 cigarettes and £209.77 per kilo of hand rolling tobacco), tobacco duty costs those with low incomes a larger proportion of their income than those on high incomes. This research looks at how tobacco duty affects households across the income distribution. It also shows how much tobacco duty costs low income households in comparison to the average household and the highest income households. Findings for 2015/16: The average household in the lowest 20% of the income distribution spent £293 on tobacco duty. The average household in the second lowest fifth of the income spectrum spent £384 on tobacco duty - 31% more than the lowest fifth. The average household in the middle fifth of the income distribution spent £405 on tobacco duty - 38% more than the lowest fifth. It is more relevant however to measure spending on tobacco duty as a percentage of disposable income. The average household in the bottom fifth of the income distribution spent 2.3% of their disposable income on tobacco duty. Tobacco duty cost the average household in the top fifth of the income distribution 0.3% of their disposable income. Tobacco duty costs the average of all households 1.0% of their disposable income. -

Report on Tobacco Taxation in the United Kingdom

Report on Tobacco Taxation in the United Kingdom Excise Social Policy Group HM Customs and Excise World Health Organization World Health Organization Report on Tobacco Taxation in the United Kingdom Tobacco Free Initiative Headquarters would like to thank the Regional Offices for their contribution to this project. WHO Regional Office for Africa (AFRO) WHO Regional Office for Europe (EURO) Cite du Djoue 8, Scherfigsvej Boîte postale 6 DK-2100 Copenhagen Brazzaville Denmark Congo Telephone: +(45) 39 17 17 17 Telephone: +(1-321) 95 39 100/+242 839100 WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia (SEARO) WHO Regional Office for the Americas / Pan World Health House, Indraprastha Estate American Health Organization (AMRO/PAHO) Mahatma Gandhi Road 525, 23rd Street, N.W. New Delhi 110002 Washington, DC 20037 India U.S.A. Telephone: +(91) 11 337 0804 or 11 337 8805 Telephone: +1 (202) 974-3000 WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific WHO Regional Office for the Eastern (WPRO) Mediterranean (EMRO) P.O. Box 2932 WHO Post Office 1000 Manila Abdul Razzak Al Sanhouri Street, (opposite Children’s Philippines Library) Telephone: (00632) 528.80.01 Nasr City, Cairo 11371 Egypt Telephone: +202 670 2535 2 3 World Health Organization Report on Tobacco Taxation in the United Kingdom Introduction1 Taxation levels The United Kingdom has among the highest levels of tobacco tax in the world1. Table 1 shows the current duty rates for tobacco products while Table 2 presents taxation levels. The latter is based on a typical pack of each product and on the most popular price category for cigarettes. Table 1 Current United Kingdom tobacco duty rates Product Duty rate Cigarettes 22% ad valorem and £94.24 (130.24 Euro) per 1 000 Tobacco Free Initiative Headquarters would like to thank the Regional Offices Cigars £137.26 (189.69 Euro) per kilogram for their contribution to this project. -

Brexit and the Control of Tobacco Illicit Trade Springerbriefs in Law More Information About This Series at Marina Foltea

SPRINGER BRIEFS IN LAW Marina Foltea Brexit and the Control of Tobacco Illicit Trade SpringerBriefs in Law More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/10164 Marina Foltea Brexit and the Control of Tobacco Illicit Trade Marina Foltea Institute of Law Studies Polish Academy of Sciences Warsaw, Poland ISSN 2192-855X ISSN 2192-8568 (electronic) SpringerBriefs in Law ISBN 978-3-030-45978-9 ISBN 978-3-030-45979-6 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-45979-6 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adap- tation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publi- cation does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

“Simplicity, Clarity and Consistency on Indirect Taxes Can Improve the UK

Indirect taxes: Improving the business environment at no cost to government Policy briefing No # 7 Indirect taxes – which include VAT, excise duties, environmental taxes and stamp duties – are mainly collected rather than borne directly by businesses. But collecting these taxes on behalf of the government brings with it compliance burdens and complexity, which the government should try “Simplicity, clarity and and minimise to allow businesses to maximise the time and money they can spend doing business. consistency on indirect By using the 2016 Business Tax Roadmap to provide simplicity, clarity and consistency on indirect tax for the taxes can improve the parliament, the government can improve the business environment by minimising the costs to business associated with collecting taxes on goods and services. These goals can UK business be achieved at no fiscal cost to the government – ensuring stability in these important revenue streams in a period of environment at no cost deficit reduction. Simplicity to the Exchequer” Through simplifying tax collection, rates and regulation the government can ease the business compliance burden associated with indirect taxes. Clarity Regular and surprise changes to indirect tax rates are unhelpful because they add to business uncertainty and to business cost due to the updates required to systems and prices. Consistency A consistent approach to indirect taxation can allow the government to meet its environmental policy goals while minimising economic distortion. Comprehensive Business Tax Roadmap: -

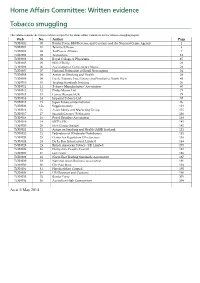

Home Affairs Committee: Written Evidence Tobacco Smuggling

Home Affairs Committee: Written evidence Tobacco smuggling This volume contains the written evidence accepted by the Home Affairs Committee for the Tobacco smuggling inquiry. Web No. Author Page TOB0032 00 Border Force, HM Revenue and Customs and the National Crime Agency 1 TOB0001 01 Terence E Rowe 6 TOB0002 02 TaxPayers Alliance 7 TOB0003 03 Transcrime 13 TOB0004 04 Royal College of Physicians 15 TOB0005 05 Will O’Reilly 21 TOB0006 06 Association of Convenience Stores 28 TOB0007 07 National Federation of Retail Newsagents 31 TOB0008 08 Action on Smoking and Health 38 TOB0009 09 Fresh, Tobacco Free Futures and Smokefree South West 45 TOB0010 10 Trading Standards Institute 56 TOB0011 11 Tobacco Manufacturers’ Association 60 TOB0012 12 Philip Morris Ltd 71 TOB0013 13 Cancer Research UK 79 TOB0014 14 Imperial Tobacco Ltd 87 TOB0015 15 Japan Tobacco International 96 TOB0033 15a Supplementary 104 TOB0016 16 Asian Media and Marketing Group 135 TOB0017 17 Scottish Grocers’ Federation 136 TOB0018 18 Petrol Retailers Association 139 TOB0019 19 SICPA UK 141 TOB0020 20 Irish Cancer Society 145 TOB0021 21 Action on Smoking and Health (ASH) Scotland 152 TOB0022 22 Federation of Wholesale Distributors 155 TOB0023 23 Center for Regulatory Effectiveness 158 TOB0024 24 De La Rue International Limited 163 TOB0025 25 British American Tobacco UK Limited 170 TOB0026 26 Derbyshire County Council 181 TOB0027 27 Len Tawn 186 TOB0028 28 North East Trading Standards Association 187 TOB0029 29 National Asian Business Association 191 TOB0030 30 Cllr Paul Rone 194 TOB0031 31 Herefordshire Council 195 TOB0034 34 HM Revenue and Customs 198 TOB0035 35 Border Force 201 TOB0036 36 Australian High Commission 204 As at 6 May 2014 Written evidence from Border Force, HM Revenue and Customs and the National Crime Agency [TOB00] Inquiry into tobacco smuggling and the trade in illicit tobacco We are grateful to the Committee for launching an inquiry into tobacco smuggling and the trade in illicit tobacco. -

S&W Narrow Margin Template

Spring Budget 2017 Commentary March 2017 Contents 1. Introduction 4 2. Personal and trust taxes 5 2.1 Increases to the rates of Class 4 NIC to be introduced 5 2.2 Income tax rates and above inflation rise in the personal allowance 5 2.3 Reduction in the dividend allowance 5 2.4 New £1,000 tax allowances for property and trading income 6 2.5 Further update on changes to the taxation of 'non-doms' 6 2.6 Consultation on rent-a-room relief to better support longer-term lettings 7 2.7 Simplifications to the cash basis and increase to the entry threshold 7 2.8 Simplified cash basis for unincorporated property businesses 8 3. Pensions, investments and capital taxes 9 3.1 Part surrenders and part assignments of life assurance policies 9 3.2 Money purchase annual allowance reduced to £4,000 from £10,000 9 3.3 Aligning the tax treatment of UK and foreign pensions 9 3.4 Qualifying recognised overseas pensions schemes (QROPS) transfers 9 3.5 Master trust pension schemes tax registration process amended 10 4. Employment taxes and payroll 11 4.1 Other employment taxes measures 11 4.2 Off-payroll working in the public sector 11 4.3 Disguised remuneration 11 4.4 Call for evidence on employee expenses 12 4.5 Employer-provided accommodation 12 4.6 Taxation of benefits in kind 12 4.7 Guidelines on making payments for employees' image rights 13 5. Business taxes 14 5.1 Corporation tax rate to fall 14 5.2 Amendments to the social investment tax relief (SITR) scheme. -

GERS: Detailed Revenue Methodology 2019-20

GOVERNMENT EXPENDITURE AND REVENUE SCOTLAND DETAILED REVENUE METHODOLOGY PAPER 2019-20 This paper outlines the various methodologies used to obtain estimates of public sector revenues in Scotland. In contrast to public sector expenditure, there is no generic best approach to estimating public sector revenue; instead each revenue is estimated using a separate methodology. This paper discusses the methodology used to apportion a share of each revenue stream to Scotland and highlights any significant changes which have been introduced in this edition of GERS. It should be noted that, as the underlying datasets used in GERS have been subject to revisions and updates, estimates may differ from previous editions of GERS even if the methodology remains unchanged. Government Expenditure and Revenue Scotland 2019-20 1 Contents Contents 2 Methodology Overview 3 Income Tax 6 National Insurance Contributions 9 VAT 10 Corporation Tax (excluding the North Sea) 11 Fuel Duties 12 Non-Domestic Rates 13 Council Tax 14 VAT refunds 15 Capital Gains Tax 16 Inheritance Tax 17 Reserved Stamp Duties 18 Land and Buildings Transaction Tax 19 Scottish Landfill Tax 20 Air Passenger Duty 21 Tobacco Duty 22 Alcohol Duty 23 Insurance Premium Tax 24 Vehicle Excise Duty 25 Environmental Levies 26 Other Taxes 27 Interest and Dividends 29 Gross Operating Surplus 30 Other receipts 32 North Sea Revenue 34 Detailed Revenue Methodology Paper Methodology Overview As highlighted in Chapter 1 of the main report, the majority of public sector receipts raised in Scotland are collected at the UK level by HM Revenue and Customs. In some cases, revenue figures can be obtained for Scotland directly. -

Pd Part07d 1..2

PRACTICE DIRECTION PART 7D PRACTICE DIRECTION 7D PART 7D PRACTICE DIRECTION CLAIMS FOR THE RECOVERY OF TAXES AND DUTIES This Practice Direction supplements CPR rule 7.9 Scope 1.1 This practice direction applies to claims by HM Revenue and Customs for the recovery of (a) Income Tax, (b) Corporation Tax, (c) Capital Gains Tax, (d) Interest, penalties and surcharges on Income Tax, Corporation Tax or Capital Gains Tax which by virtue of section 69 of the Taxes Management Act 1970 are to be treated as if they are taxes due and payable, (e) National Insurance Contributions and interest, penalties and surcharges thereon, (f) student loan repayments deducted by and recoverable from an employer under Part IV of the Education (Student Loans) (Repayment) Regulations 2000 (S.I. 2000/944), (g) Value added tax and interest and surcharges thereon, (h) Insurance premium tax and interest and penalties thereon, (i) Stamp duty land tax and interest and penalties thereon, (j) the following environmental taxes (i) landfill tax and interest and penalties thereon, (ii) aggregates levy and interest and penalties thereon, and (iii) climate change levy and interest and penalties thereon, (k) the following duties of customs and excise (i) amusement machine licence duty and penalties thereon, (ii) air passenger duty and interest and penalties thereon, (iii) beer duty and penalties thereon, (iv) bingo duty and penalties thereon, (v) cider and perry duty, (vi) excise and spirits duty, (vii) excise wine duty, (viii) gaming duty and penalties thereon, (ix) general betting duty, (x) lottery duty and penalties thereon, (xi) REDS (registered excise dealers and shippers) duty, (xii) road fuel duty and penalties thereon, (xiii) tobacco duty, and (xiv) wine and made-wine duty.