Outline I Introduction – the Metacomet Trail Page 2 II the Value of Natural Landscape Page 5 Our Attraction to Nature P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Consolidated School District of New Britain

CONSOLIDATED SCHOOL DISTRICT OF NEW BRITAIN FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Helen Yung District Communications Specialist (860) 832-4382, cell (860) 877-4552 [email protected] URBAN AND SUBURBAN TEENAGERS TAKE TEAM WORK AND DIVERSITYTO NEW HEIGHTS ATOP HUBLEIN TOWER (SIMSBURY, CT)—Climbing Hublein Tower at the Talcott Mountain State Park was the least of the challenges for a group of 35 middle and high school students conducting geological field studies along the Metacomet Ridge on July 15. The students, from six school districts dispersed from New Britain to the greater Hartford area are enrolled in the Metacomet Ridge Interdistrict Academy (MRIA). The MRIA program is funded through the State Department of Education Interdistrict Cooperative Grant and managed by CREC (Capital Region Education Council), have the task of studying the environment of the Metacomet Ridge, a rocky ridge that rises above the Connecticut Valley and stretches from Long Island Sound to far above the Massachusetts/Connecticut border. According to Dr. Nalini Munshi, lead teacher at Roosevelt Middle School’s S.T.E.M Academy, the students conducted a land cover testing that includes a site of 30 by 30 meters square squares at the bottom of Talcott Mountain State Park. The students with assistance from NBHS Teachers Joe Bosco, III and Robert Ramsey feed their data into an international website for scientists known as the Globe network, where in Scientists can access it and use it for their own research. The work that the students do is considered real time science. Referring to the land cover testing, Dr. Munshi said, “we calculate the canopy cover and ground cover and measure the height of the dominant and co dominant tree species. -

Bioscienceenterprisezone 700.Pdf

J U B E N LITTLE LEAGUE FIELDS SS IP R E E I X C Farmington River State Access Area R Second Natural Pond Last Natural Pond C V K T D A T R Y C D A Y N R R R S E WBER C A D D L R O I D D R R O U A O I R W D N T R N G S D R T T O V R A E D G D Y E R R N R C H ROM D I O L A D T R F D U D B E R W X E D N L E I R O Y O D I R R W N R V D O A R D M D L R R D N N R I E A E A I L Z T R G M A R Y N B R G A W Great Brook E N W A FARM BUILDING E E F R I G E N D F N E D O E I T R GR T N DR W R R L TO U G U O N B A N R I T D W H N T KE B X Poplar Swamp Brook NT R I L O AI S A W LE V Y D I G R C LL L T AG E G TUNXIS MEAD PARK E N N E I A R G P S L E M N 460301 S O I U A D N T R T A N ARKIN IN U L S W O AY L T A M D D O F R EN R WICK K E A D W R L O E L WHIT I T A V L R C N E O O T T T L A D N W O M T O R C O D H C U O E R R D N F P TUNXIS MEAD PARK S D T P E O A R RK R Great Brook M A I I L P N NE R T W D E S RE R M O D F Great Brook E D R S D TUNXIS MEAD PARK A T E M TOWN OF FARMINGTON R Pope Brook E S H D I O X Great Brook A N K U A H T IL L R HARTFORD COUNTY, R D TF L B RD P UN HILL E GALOW V A D TUNXIS MEAD PARK RD N HILL T O L VINE T CONNECTICUT E A G O I CT N BYRNE L I F M C R E OAK ESC FA O LA R N ND A R EN T V C T E T A 0 B P V G E 1 L D ¬« E RD EN PHEASANT HILL C H R S D M T APLE A South Reservoir V-FARM Oakland Gardens DG South Reservoir Dam R I E R D OAKLAND GARDENS FIRE STATION BIOSCIENCE A IL RD R L A GE D O U T E E ID IMBE LI N N Q R V E R L South Reservoir A T T R N O ES I C ER A R L ENTERPRISE ZONE V T A A O A T I U I D L D T O R N N R D R R B N D H L A I G T I L R C W L L D N I D R L I N E L H N D I R O N I H P T N N S S A L U I N U I A D T M A N S D I T R R T D N S U E SEWER TREATMENT PLANT S S R O O T D F . -

Giuffrida Park

Giuffrida Park Directions and Parking: Giuffrida Park was originally part of an area farmed in To get to Giuffrida Park, travel along I-91 either north or the late 1600’s and early 1700’s by Jonathan Gilbert and south. Take Exit 20 and proceed west (left off exit from later Captain Andrew Belcher. This farm, the first European north or left, then right from the south) onto Country Club settlement in this region, became known as the “Meriden Road. The Park entrance is on the right. Parking areas are Farm”, from which the whole area eventually took its name. readily available at the Park. Trails start at the Crescent Today, the Park contains 598 acres for passive recreation Lake parking lot. and is adjacent to the Meriden Municipal Golf Course. Permitted/Prohibited Activities: Located in the northeast corner of Meriden, the trails connect to the Mattabessett Trail (a Connecticut Blue-Blazed Trail) Hiking and biking are permitted. Picnic tables are also and are open to the general public. The trails have easy available. Crescent Lake is a reserve water supply terrain particularly around the Crescent Lake shore with therefore, swimming, rock climbing, and boating are steeper areas along the trap rock ridges ascent of the prohibited. Fishing is also prohibited. Metacomet Ridge and approaching Mt. Lamentation. Mount Lamentation was named in 1636 when a member of Wethersfield Colony became lost and was found by a search party three days later on this ridge, twelve miles from home. There is some controversy whether the Lamentation refers to his behavior or that of those looking for him. -

(King Philip's War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial

Connecticut Unscathed: Victory in The Great Narragansett War (King Philip’s War), 1675-1676 Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Major Jason W. Warren, M.A. Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: John F. Guilmartin Jr., Advisor Alan Gallay, Kristen Gremillion Peter Mansoor, Geoffrey Parker Copyright by Jason W. Warren 2011 Abstract King Philip’s War (1675-1676) was one of the bloodiest per capita in American history. Although hostile native groups damaged much of New England, Connecticut emerged unscathed from the conflict. Connecticut’s role has been obscured by historians’ focus on the disasters in the other colonies as well as a misplaced emphasis on “King Philip,” a chief sachem of the Wampanoag groups. Although Philip formed the initial hostile coalition and served as an important leader, he was later overshadowed by other sachems of stronger native groups such as the Narragansetts. Viewing the conflict through the lens of a ‘Great Narragansett War’ brings Connecticut’s role more clearly into focus, and indeed enables a more accurate narrative for the conflict. Connecticut achieved success where other colonies failed by establishing a policy of moderation towards the native groups living within its borders. This relationship set the stage for successful military operations. Local native groups, whether allied or neutral did not assist hostile Indians, denying them the critical intelligence necessary to coordinate attacks on Connecticut towns. The English colonists convinced allied Mohegan, Pequot, and Western Niantic warriors to support their military operations, giving Connecticut forces a decisive advantage in the field. -

News Notes Conserving the Land, Trails and Natural Resources of Connecticut Since 1895

NEWSLETTER OF THE CONNECTICUT FOREST PARK ASSOCIATION CFPANews Notes Conserving the land, trails and natural resources of Connecticut since 1895. Winter 2008 Volume 1 Issue #2 Annual Fund Easier than Trail Mix CFPA wants you! Ever to Support Many Hands on the (to volunteer for special CFPA kicks off our 2008 Trails, Annual Awards events). Eastern Annual Fund with to Trail Managers, and Mountain Sports easier donation options tally of Trail hours. provides CFPA Club Day than ever before. Page 4-5 benefits to members. From the Executive Wedding Bells & Happy Page 5 Director’s Desk Trails brings support to CFPA’s Image Problem. CFPA. Giving options WalkCT Gains Ground Staff updates - Awards abound. New program makes and new family. Page 3 strides to connect you Page 2 with good hikes. Page 6 Conservation Center. For several years influence Connecticut’s forest resources, Partnership at after the 1964 gift, CFPA was contracted either now or in the future. Forest by the state to operate the educational landowners, foresters and loggers, scout Goodwin Center center. In 2005, after 2+ years of and other youth groups, and municipal Renewed minimal activity at the Center, we were commissioners are some key examples. instrumental in forming the “Goodwin The foundation of the Center’s On October 1, CFPA opened a new Collaborative”: a 3-way partnership educational programs is demonstration: chapter in educational partnership when on-the-ground examples of good forest we officially began directing programs and wildlife stewardship put in place at the Goodwin Forest Conservation and documented. These demonstrations Education Center in Hampton, CT. -

Appalachian Trail History Grandma Gatewood’S Walk

Appalachian Trail History Grandma Gatewood’s Walk October 1921 “An Appalachian Trail: A Project in Regional Planning.” by Benton MacKaye appears in the Journal of the American Institute of Architects. [TY] March 3, 1925 Appalachian Trail Conference (ATC) established. [TY] May 1928 A second ATC meeting… The reworded purpose of the organization was to “promote, establish and maintain a continuous trail for walkers, with a system of shelters and other necessary equipment…” [TY] 1931 “…nearly half the trail had been marked – but mostly in the Northeast, where many trails had long been established and hiking communities had a history.” [p. 47] June 1931 Myron H. Avery elected to first of seven consecutive terms as ATC Chairman.”1 [TY] “[Myron] Avery… helped organize hiking clubs and plan undeveloped sections [of the A.T.]” [p. 47] 1933 “By 1933, the U.S. Forest Service and the southern clubs reported their third of the Trail completed.” [TY] 1934 “Clubs reported completion of 1,937 miles of trail.” [TY] 1935 “The Appalachian Trail – first in Maine, later in southern states – became an item on the agenda of the Depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps.” [TY] 1936 “[Myron Avery] …became the first ‘2,000-miler’ on the footpath.” “By that time, he had walked and measured every step of the flagged or constructed route...” [Note he accomplished this in sections, not in one continuous hike.] [TY] August 14, 1937 “Appalachian Trail completed as a continuous footpath.” [TY] October 15, 1938 “…the National Park Service and the U.S. Forest Service executed an agreement to promote the trailway concept on the 875 miles of federal lands along the A.T. -

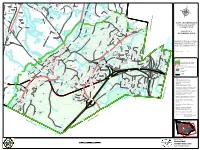

Colonial Consequence: King Philip’S War

Colonial Consequence: King Philip’s War Name: A devastating outcome of European colonialism in the New World was a series of wars that involved and affected both Europeans and Native Americans. The bloodiest of these wars was King Philip’s War. This exercise uses a map made in 1677 by John Foster, an English colonist who was attempting to illustrate the locations of the significant battles of King Philip’s War. Before beginning the worksheet, note the compass rose on the bottom of the map. What direction is placed at the top?_____________________ Precursors to the Conflict – Land Encroachment The English colonists were especially guilty of land encroachment. By the time Metacomet, known as King Philip to the English, became Massasoit (“Great Leader”) of the Wampanoag Confederacy, the English had already founded several towns in Wampanoag territory, even though Metacomet’s father had been a loyal ally to the English. A few of these towns include: Hartford Winsor Springfield Hadly Northampton Deerfield Find each town on John Foster’s Map. What do each of these towns have in common? Why would European settlers be attracted to this area? Find the territories of the Pequids, the Nipnucks, and the Narragansett on Foster’s map. Whose territory is closest to Plymouth? Why do you think the Wampanoag Territory wasn’t included? 1 Precursors to the Conflict – Suspicions and Rumors Metacomet’s older brother, Wamsutta, had been Massasoit for only a year when he died suspiciously on his way home from being detained by the governor of Plymouth Colony. Metacomet, already distrustful towards Europeans, likely suspected the colonists of assassinating his brother. -

FAQ: HR 799 & S. 403: North Country National Scenic Trail Route Adjustment

FAQ: HR 799 & S. 403: North Country National Scenic Trail Route Adjustment Act Exactly what does HR 799/S. 403 call for? These bills simply amend the National Trails System Act (16 U.S.C. 1244(a)(8)) by: (1) Substituting new language delineating the North Country National Scenic Trail’s total length (from 3200 to 4600 miles); (2) Re-defining the eastern terminus as the Appalachian National Scenic Trail in Vermont; and (3) Substituting a new map reference for the original, showing the Minnesota Arrowhead and the eastern terminus extension. So what does this accomplish? H.R. 799/S. 403 completes the original vision for the North Country National Scenic Trail (NCNST) by extending the eastern terminus to link with the Appalachian Trail in Vermont. And, this legislation legitimizes the de-facto route of the NCNST in Minnesota since 2005, with the formal inclusion of Minnesota’s Superior Hiking, Border Route and Kekekabic Trails as officially part of the North Country National Scenic Trail (NCNST). Wait--going from 3200 to 4600 miles sounds like a lot more than that! The original 1980 authorizing legislation contains the language “a trail of approximately 3200 miles.” This was clearly an estimate, since almost none of the NCNST had been built when the 1970’s feasibility studies estimated its length. Since then much of the NCNST has been constructed and the route identified; the trail is on the ground and we have more sophisticated tools for measuring it. As it turns out, in order to carry out Congress’ intent for the original NCNST the actual mileage is closer to 4100 miles, even without the Minnesota Arrowhead or the eastern terminus extension into Vermont (which add another 500 miles). -

Environmental Review Record

FINAL Environmental Assessment (24 CFR Part 58) Project Identification: Meriden Mills Apartments Disposition and Related Parcel Assembly Meriden, CT Map/Lots: 0106-0029-0001-0003 0106-0029-0002-0000 0106-0029-001A-0000 Responsible Entity: City of Meriden, CT Month/Year: March 2017 Meriden Mills Apartments Disposition and Related Parcel Assembly, City of Meriden, CT Environmental Assessment Determinations and Compliance Findings for HUD-assisted Projects 24 CFR Part 58 Project Information Responsible Entity: City of Meriden, CT [24 CFR 58.2(a)(7)] Certifying Officer: City Manager, Meriden, CT [24 CFR 58.2(a)(2)] Project Name: Meriden Commons Project Location: 144 Mills Street, 161 State Street, 177 State Street, 62 Cedar Street; Meriden CT. Estimated total project cost: TBD Grant Recipient: Meriden Housing Authority, Meriden CT. [24 CFR 58.2(a)(5)] Recipient Address: 22 Church Street Meriden, CT 06451 Project Representative: Robert Cappelletti Telephone Number: 203-235-0157 Conditions for Approval: (List all mitigation measures adopted by the responsible entity to eliminate or minimize adverse environmental impacts. These conditions must be included in project contracts or other relevant documents as requirements). [24 CFR 58.40(d), 40 CFR 1505.2(c)] The proposed action requires no mitigation measures. 2 4/11/2017 4/11/2017 Meriden Mills Apartments Disposition and Related Parcel Assembly, City of Meriden, CT This page intentionally left blank. 4 Meriden Mills Apartments Disposition and Related Parcel Assembly, City of Meriden, CT Statement of Purpose and Need for the Proposal: [40 CFR 1508.9(b)] This Environmental Assessment (EA) is a revision of the Final EA for Meriden Mills Apartments Disposition and Related Parcel Assembly prepared for the City of Meriden (“the City”) in October 2013. -

Municipal Plan and Regulation Review, the Committee Provided Municipal Land Use Regulations and Pcds for Most of the Participating Towns

MUNICIPAL PLAN & REGULATION REVIEW LOWER FARMINGTON RIVER & SALMON BROOK WILD AND SCENIC STUDY COMMITTEE March 2009 Avon Bloomfield Burlington Canton East Granby Farmington Granby Hartland Simsbury Windsor Courtesy of FRWA MUNICIPAL PLAN & REGULATION REVIEW LOWER FARMINGTON RIVER & SALMON BROOK WILD AND SCENIC STUDY COMMITTEE MARCH 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS • EXECUTIVE SUMMARY • INTRODUCTION • PROJECT OVERVIEW AND METHODOLOGY • STATUTORY FRAMEWORK • DEFINITIONS & ACRONYMS • STUDY CORRIDOR SUMMARY • TOWN SUMMARIES o Avon o Bloomfield o Burlington o Canton o East Granby o Farmington o Granby o Hartland o Simsbury o Windsor • REVIEW CHART o Geology o Water Quality o Biodiversity o Recreation o Cultural Landscape o Land Use EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The proposed designation of the lower Farmington River and Salmon Brook as a Wild and Scenic River, pursuant to 16 U.S.C. §§ 1271 to 1287 (2008), is a regional effort to recognize and protect the River itself and its role as critical habitat for flora and fauna, as a natural flood control mechanism, and as an increasingly significant open space and recreational resource. A review of the municipal land use regulations and Plans of Conservation and Development (“PCD”) for the ten towns bordering the River within the Lower Farmington and Salmon Brook Watersheds (the “Corridor Towns”) was conducted (the “Review”). The results of the Review identify and characterize the level of protection established in local regulations for each of the six different Outstanding Resource Values (“ORVs”), or natural, cultural, or recreational values of regional or national significance associated with the Lower Farmington River and Salmon Brook. Designation of the Lower Farmington River and Salmon Brook as Wild and Scenic will not impact existing land use plans and regulations in the ten Corridor Towns. -

AQUIFERPROTECTIONAREA SP Lainville

d n H L Bradley Brook Beaverdam Pond Williams Pond r r R u D H r D s D t d Taine and y ell S 4 d Mountain c 7 Upl nd xw rn e Rd a a e 6 n i m M F n SV k 1 t L l or t n R s r s n o l N a Morley Elementary School R H l y Fisher Meadows gg s E N ! e L w Pi u e r H b a o b r S m d r n ld D W R e l b k D O'Larrys Ice Pond No 1 t o el c T e e r r A r o e a w a R a Ratlum Mountain Fish & Game Club Pond i t x y a Edward W Morley School u r f S r d r M t h r A 162 a d v D r l h a i i n h l r d R o v s y Charles W House u n R L C l u A o n l P l a o r Av ry l ll n e t i e d a n M M D w r n R n i e m k H L c D S e d Farmington Woods 2 H e B 4 v t o n d R R o o l a r i S i d Fisher Meadows e n a C e n l B 167 p V o M S r i l e lton St D r A A 133 F l V l r r o D u i S e C V i M n v s l l R o S e r D u v B e H b u o D y T H y A 156 A A e o q l ob n l m S e o d S i e t i e t A 162 r S n S r i o s n r n o v r d H R e l i u t s ar Av Punch Brook n r l b a h t e n r v c rm l s e e r Trout Brook R h o o D S c b n i O e a d l e R e l r v m o k l e L t A r t s d W s r i n s d r r West Hartford Reservoir No 5 a o l a R f o C d o r R tm d r e r S f i d o h i W o o i y Taine Mountain W v D e a t s n l a u t d R n i l W L e k r f v l r y A V O N Dyke Pond D D L a b r t e d W B e L l n o a r R o y t A R a n y i S g r d a r Punch Brook Ponds J n g y e i o d M a d B S d r B n a d e t a a y A s i i n b o H E r P d t G L e c r r d L r t R w il n y v d n o e f l a il H A P x r e t u e i n m nc M t l i w h B P e t e l R e r e a i S R o Norw s ! o ood Rd t d Bayberry -

Management Plan 2013

Upper Housatonic Valley National Heritage Area Management Plan 2013 Housattonio c River, Kenene t,, Cononneccticiccut. PhoP tograph by the Houo satoninic Valll eyy AssAss ociiatiion. Prepared by: Upper Housatonic Valley Heritage Area, Inc. June 2013 24 Main Street PO Box 493, Salisbury, CT 06068 PO Box 611 Great Barrington, MA 01257 Table of Contents Chapter 1: Purpose and Need 1 2.6.2 Connections to the Land 15 1.1 Purpose of this Report 1 2.6.3 Cradle of Industry 17 1.2 Definition of a Heritage Area 1 2.6.4 The Pursuit of Freedom & Liberty 19 1.3 Significance of the Upper Housatonic Valley 2.7 Foundations for Interpretive Planning 21 National Heritage Area 1 Chapter 3: Vision, Mission, Core Programs, 1.4 Purpose of Housatonic Heritage 3 and Policies 22 1.5 Establishment of the Upper Housatonic Valley 3 National Heritage Area 3.1 Vision 22 1.6 Boundaries of the Area 4 3.2 Mission 22 3.3 The Nine Core Programs 23 Chapter 2: Foundation for Planning 5 3.4 The Housatonic Heritage “Toolbox” 28 2.1 Legislative Requirements 5 3.5 Comprehensive Management Policies 30 2.2 Assessment of Existing Resources 5 3.5.1 Policies for Learning Community Priorities 30 2.3 Cultural Resources 5 3.5.2 Policies for Decision-Making 32 2.3.1 Prehistoric and Native American Cultural Resources 5 Chapter 4: Development of the Management Plan 33 2.3.2 Historic Resources 7 4.1 Public Participation and Scoping 33 2.4 Natural Resources 9 4.2 Summary of Issues Raised in Scoping 33 2.4.1 Geologic Resources 9 4.3 Management Scenarios 34 2.4.2 Geographic Area 9 4.3.1 Scenario 1: Continue the Nine Core 2.4.3 Ecosystems 10 Programs 34 2.4.4 Conservation Areas for Public 4.3.2 Scenario 2: Catalyst for Sharing Enjoyment 12 our Heritage 34 2.5 Recreational Resources 13 4.3.3 Scenario 3: Promote Regional Economic Vitality and Address 2.6 Interpretive Themes 14 Regional Heritage 35 2.6.1.