Book Reviews 139

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Security, Mutual Vulnerability, and Sustainable Development: a Critical View

Human Security, Mutual Vulnerability, and Sustainable Development: A Critical View by Jorge Nef This essay is an attempt to provide a historical and structural frame of reference for the study of human security, from a distinctively “foreign” standpoint.1 More specifically, the essay explores its various meanings, intellectual roots, and antecedents, as well as, the debates and controversies about its significance and its implications for the conduct of global politics and foreign policy. In addition, and more substantively, the aim of the paper is to advance some tentative observations regarding the interface among peace, human rights, and sustainable development in a post–Cold War context. The main thesis in this analysis is that growing interdependence, a main consequence of integration and globalization, creates mutual vulnerability for all nations, groups, and individuals. With the end of World War II, military security and economic development became the parameters of what was then construed as a rigid bipolar world system. The end of the Cold War spearheaded a tendency to celebrate unipolarity and the “end of history”2 as the inevitable result of globalization and the work of market forces. However, this neofunctional utopia came to an abrupt end with the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. In its stead, an all-encompassing and already evolving mutation of the national security doctrine reemerged, centered not on deterrence but on preemption. Its prime manifestation has been the War on Terror. As with the Cold War, but without the constraint of mutual deterrence, security is perceived once again as an endless zero-sum game.3 In this new context, the once unthinkable, yet omnipresent, negative-score game, has become a distinct probability. -

Panel Chair Biographies Margaret

Revised on October 14, 2014 Panel Chair Biographies Margaret Boittin is Professor at Osgoode Hall Law School. Previously, she was a Fellow at the Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law at Stanford University. She has a JD from Stanford, and is completing her PhD in Political Science at the University of California, Berkeley. In addition, she holds an MA in Political Science from UC Berkeley and a BA from Yale University. Her PhD dissertation is on the regulation of prostitution in China. She is also conducting research on human trafficking in Nepal, and criminal law policy and local enforcement in the United States. Bilingual in French and English, Boittin is also fluent in Mandarin Chinese, and proficient in Russian and Spanish. Her primary teaching interests are property law, international law, criminal law, state and local government law, Chinese law, comparative law, and empirical methods. Jutta Brunnée is the Interim Dean, Professor of Law and Metcalf Chair in Environmental Law at the University of Toronto, Faculty of Law. Her teaching and research interests are in the areas of Public International Law and International Environmental Law. Her recent work has focused on international law and international relations theory, compliance with international law, the inter-state use of force, domestic application of international law, multilateral environmental agreements, climate change issues and international environmental liability regimes. Professor Brunnée is also the co-author of Legitimacy and Legality in International Law: An Interactional Account (Cambridge University Press, 2010), which was awarded the American Society of International Law’s 2011 Certificate of Merit for preeminent contribution to creative scholarship. -

Economic Migrants Or Refugees? Trends in Global Migration

Economic Migrants or Refugees? Trends in Global Migration Session Proceedings January 12, 2000 Hosted by The Maytree Foundation in cooperation with The Caledon Institute of Social Policy & The Canadian Institute of International Affairs St. Lawrence Centre for the Arts, Jane Mallett Theatre 27 Front Street East, Toronto, Ontario Published by the Caledon Institute of Social Policy ISBN 1-894598-01-6 Economic Migrants or Refugees? Trends in Global Migration Table of Contents Introduction 3 Keynote Speaker Professor Ivan Head 4 Director, Liu Centre for the Study of Global Issues University of British Columbia Forum Moderator Hugh Segal 12 President, Institute for Research on Public Policy Panelists Susan Davis 14 Co-Author, “Not Just Numbers” The Honourable Barbara McDougall 19 President, Canadian Institute of International Affairs Jeffrey Reitz 22 Professor of Sociology, The University of Toronto Demetrios Papademetriou 26 Co-Director, International Migration Policy Program Carnegie Endowment for International Peace T. Sher Singh 30 Lawyer and Columnist (The Toronto Star) Questions from the Audience 35 Concluding Remarks Professor Ivan Head 39 Ministerial Address The Honourable Elinor Caplan 40 Minister of Citizenship and Immigration Appendix A - About the Speakers 47 Appendix B - About the Sponsors The Maytree Foundation 48 The Caledon Institute of Social Policy 49 The Canadian Institute of International Affairs 50 2 Caledon Institute of Social Policy Economic Migrants or Refugees? Trends in Global Migration Introduction The Maytree Foundation, in conjunction of oppression that might qualify one as a refu- with the Caledon Institute of Social Policy and gee? the Canadian Institute of International Affairs, sponsored the forum Economic Migrants or Refu- · Does Canada have an obligation to these new gees? Trends in Global Migration on January arrivals? Do wealthy countries have a moral 12, 2000, in Toronto. -

Ivan Head Put the Third World and the Arctic on Canada's Map Of

iE'DRC4LIb 0592-2 MAI 1988 Head MAY 1988 for global affairs lvan Head Out the, Third I p:R A i (if and the/ 'K3i4 f k6tic A4 S( jitF 'f on map' h t i tfF of!for9n policy '' vu Wit;s 0 f( ui s A M Y I THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SATURDAY, MAY 28,1088 b5 SUITE THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SATURDAY, MAY 28, 1988 CONTINUED 2. BY JUDY STEED The Globe and Mail IS REPUTATION precedes him: Ivan Wanderlust is in his blood. His Head was Canada's Kissinger, for eight mother, Birdie Larkin, came from years the "special assistant to the prime Prince Edward Island, descended minister," responsible for "foreign policy from a Maritimes family that in- and the conduct of international rela- cluded the captain of a clipper ship tions. " who was lost at sea. His Aunt Belle, Pierre Elliott Trudeau, once a globe- who at the turn of the century was trotting leftist, developed a passion for widowed young, moved to northern foreign affairs while occupying the highest office in the British Columbia, ran her own busi- -id; under Mr. Head's tutelage, Prime Minister ness "and prospered to the extent . udeau pursued an activist foreign policy that gave that she could vacation in Europe - Canada a high profileon the global scene. this was before the First World War," says Mr. Head The Trudeau-Head duo mounted a sophisticated with proud emphasis. A more contemporary relative is campaign to defend Canada's Arctic sovereignty former Tory member of Parliament David MacDonald, against U.S. -

S:\CAB\Finding Aids\Political and Social Heritage Division\1900

FONDS DU TRÈS HONORABLE PIERRE ELLIOTT TRUDEAU THE RT. HON. PIERRE ELLIOTT TRUDEAU FONDS MG 26 O 19 Instrument de recherche no 1900 \ Finding Aid No. 1900 SÉRIE DU PERSONNEL STAFF SERIES 1968-1984 Préparé par la Section des archives Prepared by the Political Archives Section, politiques, Division des manuscrits Manuscript Division TABLE DES MATIÈRES/TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................... ii SUB-SERIES ............................................................... ii -Volumes 1-11: Gordon Ashworth 1983-1984 ................................ ii -Volumes 12-26: Tom Axworthy 1976-1984 ................................. ii -Volumes 27-36: Denise Chong 1982-1984 .................................. ii -Volumes 37-46:David Crenna 1981-1984 ................................... ii -Volumes 47-50:Gilles Dufault 1971-1976 ................................... iii -Volumes 51-75, 283-286 (Electronic Records): Michael Langill 1981-1984 ........ iii -Volumes 76-83: Peter Larsen 1981-1984 .................................... iii -Volumes 84-87: Robert Pace 1982-1984 .................................... iv -Volumes 88-96: Florence Ievers 1982-1984 ................................. iv -Volumes 97-114: Heather Peterson 1982-1984 ............................... iv -Volumes 115-134: Geoffrey O’Brien 1980-1981 ..............................v -Volumes 135-159: Ivan Head 1968-1978 ....................................v -Volumes 160-186: Ted Johnson 1980-1984 ...................................v -Volumes 187-188: -

FROM IMPERIALISM to British COLUMBIA

A FROM IMPERIALISM TO INTERNATIONALISM IN BRiTISH COLUMBIA EDUCATION AND SOCIETY, 1900 TO 1939 by WAYNE CHARLES NELLES B.A., Simon Fraser University, 1979 M.A., Simon Fraser University, 1984 A THESIS SUBMLTED iN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Educational Studies) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April 1995 ØWayne Charles Nelles, 1995 ___________________ In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. (Signature) Department of hica%o> / $%6j’ The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date / /, “9 DE-6 (2/88) 11 Abstract This study argues for a transition from imperialism to internationalism in British Columbia educational thought, policy and practice from 1900 to 1939. Three contrasting and complementary internationalist orientations were dominant in British Columbia during that period. Some educators embraced an altruistic “socially transformative internationalism” built on social gospel, pacifist, social reform, cooperative and progressivist notions. This contrasted with a self-interested “competitive advantage internationalism,” more explicitly economic, capitalist and entrepreneurial. A third type was instrumental and practical, using international comparisons and borrowing to support or help explain the other two. -

Canada and the Maritime Arctic

Canada and the Maritime Arctic © The authors 2020 North American and Arctic Defence and Security Network c/o School for the Study of Canada Trent University Peterborough, ON LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION Canada and the Maritime Arctic: Boundaries, Shelves, and Waters / P. Whitney Lackenbauer, Suzanne Lalonde, and Elizabeth Riddell-Dixon Issued in electronic and print formats ISBN: 978-1-989811-03-1 (pdf) 978-1-989811-02-3 (paperback) 1. Arctic regions – legal aspects. 2. Sovereignty, International – Arctic regions. 3. Arctic regions – boundary disputes. 4. Arctic regions – Canada. 5. Arctic Sovereignty. 6. Canada – Arctic. 7. Jurisdiction, Maritime – Arctic regions. I. Lackenbauer, P. Whitney, author II. Lalonde, Suzanne, author III. Riddell- Dixon, Elizabeth, author IV. North American and Arctic Defence and Security Network, issuing body V. Title. Page design and typesetting by P. Whitney Lackenbauer Cover design by Jennifer Arthur-Lackenbauer Please consider the environment before printing this e-book Canada and the Maritime Arctic Boundaries, Shelves, and Waters P. Whitney Lackenbauer, Suzanne Lalonde, and Elizabeth Riddell-Dixon TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction by P. Whitney Lackenbauer and Suzanne Lalonde ....................... i 1. The Beaufort Boundary: An Historical Appraisal of a Maritime Boundary Dispute by P. Whitney Lackenbauer ............................................... 1 2. Canada’s Arctic Submission to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf by Elizabeth Riddell-Dixon ....................................... -

Torrens Titles to Minerals in Alberta

TORRENS TITLES TO MINERALS IN ALBERTA THEODORE B. F. RIJOFF* London Almost one hundred years ago' Mr. Robert Torrens (as he then was), a mere layman, but one who was imaginative and tenacious to a degree, carried through the South Australian legislature, in the teeth of a most derisive and bitter opposition from members of the legal profession, a measure by which he proposed to make the technical process of conveying titles to land reliable, simple, cheap, speedy and suited to the needs of the community' Not long afterwards, his system of land titles spread like a forest fire throughout Australia and New Zealand,' and a spark was blown across the Pacific Ocean to Canada where his ideas were adopted widely, though sometimes tinged with the English system of re- gistered titles,' a system which was created independently of, but almost simultaneously with the Torrens system.' It is lamentable, therefore, that one hundred years after *A Solicitor of the Supreme Court of Judicature in England ; a Registrar at Her Majesty's Land Registry, London. The opinions expressed in this article are my own and are in no way prompted by my official position . i The Real Property Act, 1857 (21 Vict., No. 15, of South Australia) was passed into law January 27th, 1858, and became operative on July lst, 1858. 'The preamble reads: "Whereas the inhabitants of the Province of South Australia are subjected to losses, heavy costs and much perplexity by reason that the laws relating to the transfer and encumbrance of free- hold and other interests in land are complex, cumbrous, and unsuited to the requirements of the said inhabitants . -

Fabric Crafts and Poetry: the Art of Development Education in Canada

Focus Fabric crafts and poetry: The art of development education in Canada New forms of development education are emerging in Canada. These aim to engage people in critical dialogue by creating new lenses through which to see and explore the world. Budd Hall and Darlene Clover look at the importance of innovative learning models through examples of arts/crafts-based development education in Canada. “Our strategy should be not only to confront the empire but to mock it…with our art…and our ability to tell our own stories”. Arundhati Roy Introduction In the mid 20 th century people travelled to the majority world and returned home with stories that often contradicted the dominant narratives of the day. They argued that there were in fact rich and powerful indigenous knowledge systems still at work and that poverty was a result of global trade, colonisation, patriarchy and the growing need for resources in rich countries. Development education is the term which Canadians used to describe this counter learning and teaching. In the early 21 st century the dominant discourse of the powerful has reached fever pitch. Economic globalisation, in spite of daily evidence to the contrary, is said to be the universal pathway to well being. A warped vision of democracy is being sold as our global salvation whilst the solution to global conflict is military power and force. Ideas around a tide of human security and prosperity that would float all boats have been overshadowed by views that sink us through an isolation and polarisation of critical voices. The greatest global crime may not be solely the ruthless scouring of the world for oil and natural resources but rather the perpetuation of a myth that there is only one way for humanity to organise, teach and learn which ultimately chips away at our ability to re-create and re-imagine the world. -

Lougheed: Building a Dynasty and a Modern Alberta from the Ground Up

LOUGHEED: BUILDING A DYNASTY AND A MODERN ALBERTA FROM THE GROUND UP Lee Richardson Charismatic and articulate, organized and well prepared, Peter Lougheed seemed destined to lead the Alberta Progressive Conservatives out of the wilderness and into the modern era. From a party that had no seats in the Legislature when he became its leader, he built a political dynasty that endures to this day. Not only did he build the modern Alberta, he was a compelling figure on the national stage. Lee Richardson, a close adviser and friend, shares this intimate profile of the Best Premier of the Last 40 Years. Aussi charismatique qu’éloquent, doué de grandes qualités d’organisation et de planification, Peter Lougheed était tout désigné pour faire passer les progressistes- conservateurs albertains de la ruralité à l’ère moderne. D’un parti qui ne détenait aucun siège à l’Assemblée législative lorsqu’il en a pris les commandes, il a constitué une dynastie politique dont l’influence reste aujourd’hui déterminante. Il a non seulement modernisé l’Alberta mais en a fait un acteur décisif de la scène nationale. Lee Richardson, qui fut toutes ces années son proche conseiller et ami, brosse un portrait intime du meilleur premier ministre provincial des 40 dernières années. he Dirty 30s were not kind to Alberta. The Great at an early age to work hard, be positive, be self-assured and Depression had ravaged farms, families and fortunes. believe in himself. At home, “excellence in any pursuit was T In Calgary, as his grandson watched with forebod- not only to be desired, it was expected. -

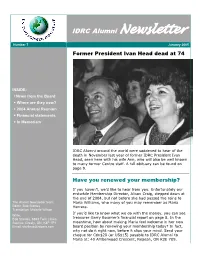

IDRC Alumni Newsletter

IDRC Alumni Newsletter Number 7 January 2005 Former President Ivan Head dead at 74 INSIDE: . News from the Board . Where are they now? . 2004 Annual Reunion . Financial statements . In Memoriam IDRC Alumni around the world were saddened to hear of the death in November last year of former IDRC President Ivan Head, seen here with his wife Ann, who will also be well known to many former Centre staff. A full obituary can be found on page 9. Have you renewed your membership? If you haven’t, we’d like to hear from you. Unfortunately our erstwhile Membership Director, Alison Craig, stepped down at the end of 2004, but not before she had passed the reins to The Alumni Newsletter team: Maria Williams, who many of you may remember as Maria Editor: Bob Stanley Herrera. Translation: Michèle Wilson If you’d like to know what we do with the money, you can see Write: Bob Stanley, 6853 Twin Lakes treasurer Gerry Bourrier’s financial report on page 8. In the Avenue, Greely, ON K4P 1P1 meantime, how about making Maria feel welcome in her new Email: [email protected] board position by renewing your membership today? In fact, why not do it right now, before it slips your mind. Send your cheque for Cdn$20 (or US$15) payable to IDRC Alumni to Maria at: 40 Amberwood Crescent, Nepean, ON K2E 7B9. page 2 IDRC Alumni Newsletter From the Board The Board of IDRC Alumni, in adopting a general statement of purpose of the Alumni agreed that a primary role for our organization is to support and serve as advocates to further the programme initiatives of IDRC. -

A History of the Law Faculty

A HISTORY OF THE LAW FACULTY A HISTORY OF THE LAW FACULTY JOHN M. LAW and RODERICK J. WOOD. The authors examine the history of the Faculty of Les auteurs relatent l'histoire de la faculte de Law at the University of Alberta. Beginning with a droit de l'Universitt! de /'Alberta. /Is commencent look at the early requirements to practice law in par examiner la formation exigee des tout premiers Alberta, the authors discuss the events leading to avocats, discutent des evenements qui ont conduit a the establishment of the first permanent law school l'etablissement de la premiere faculte de droit in the province. An analysis of the evolution of the permanente de la province et suivent /'evolution de Faculty is conducted. Along the way, the important la Faculte. /Is font etat des contributions contributions of many individuals, from John A. importantes de nombreuses personnalites - de Weir to Wilbur Bowker, are acknowledged. John A. Weir a Wilbur Bowker. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION . 1 II. EARLY FOUNDATIONS . 1 III. CREATION OF THE LAW FACULTY ..................... 4 IV. ESTABLISHMENT OF THE FULL-TIME LAW FACULTY ...... 8 V. GROWTH OF THE LAW FACULTY ..................... 15 VI. THE MODERN LAW FACULTY ........................ 19 I. INTRODUCTION As with many institutions in our society, the Faculty of Law at the University of Alberta can be considered a living entity. It has a past, a present and a future. Its future cannot be anticipated and its present cannot be properly understood unless there is some comprehension of its past. The following history of the Faculty is neither detailed nor comprehensive.