Final Environmental Impact Statement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metolius River LLID: 1212861445954

ODFW AQUATIC INVENTORY PROJECT STREAM REPORT STREAM: Metolius River LLID: 1212861445954 BASIN: Deschutes River HUC NUMBER: 17070301 DATES: June 21 - July 14, 2011 SURVEY CREWS: Frank Drake / Mark McLaughlin REPORT PREPARED BY: Staci Stein USGS MAPS: Black Butte, Candle Creek, Prairie Spring Farm ECOREGION: Cascade Eastern North BASIN AREA: 795 km2 FIRST ORDER TRIBUTARIES: 50+ GENERAL DESCRIPTION: The Metolius River habitat survey began at the confluence of Jefferson Creek and continued upstream 21,049 meters to end at the headwater springs surfacing from the hillside. Nine reaches were designated based on changes in channel morphology and contributions from major tributary junctions. The river channel was constrained by terraces and hillslopes. Land uses were mature trees (50-90cm dbh), large timber (30-50cm dbh), rural residential property, and second growth timber (15-30cm dbh). The crew floated the river with inflatable kayaks in the lower reaches (Reaches 1-4) where the river was too swift and deep for safe and accurate measurements by foot. The upper reaches (Reaches 5-9) of the river were surveyed by foot. Overall stream substrate was a combination of gravel (36%), sand (24%), cobble (18%), and silt and organic fines (11%). The stream habitat types were predominately riffles (50%), scour pools (28%), and rapids (14%). Large wood debris volume ranged from 1.5-17.8m3/100m. The trees observed most frequently in the riparian zones were conifers ranging from 3-50cm dbh (based on thirty-one riparian transects). REACH DESCRIPTIONS: Reach 1: (T12S-R09E-S02NE) Length 3029 meters. Reach 1 began at the confluence with Jefferson Creek and continued to Bridge 99. -

Jefferson County General Reports

JEFFERSON COUNT¥ ENVIRONMENTAL GEOLOGY STUDY Geologist (125 days@ $125/day) • $ 15,600 * Editing (65 days@ $77/day) • 5,000 * Cartography. 4,000 * Supplies. • 750 * Printing. • 4,900 Travel and per diem Per diem - $27.50 x 60 days •••••••••• • $1,650 Travel to job - 566 (mi. round trip) x 12 x 14¢. 948 Travel on job - 100 x 60 x 14¢ • • •••• 840 3,438 * Overhead on* items above - $28,788 x 20%. 5,757 TOTAL. • • • $ 39,445 Maps: (1) Geology - 4 or 5 color (1 inch= 3 miles) (2) Mineral deposits (combine with geology?) (3) Urban - 7~' - 1:24,000 (black and white) Bulletin Start August 1 if no ERDA uranit.nn study Start March 1, 1978, if ERDA uranium study Contract for flat fee - 60% from county •••••••••••••• $ 24,000 )< Gs-C!J~C-/j' ~ )( -· /-J t:Cl rT,; >-J c; .,, /~ 6DO ;,, Cdjvz To_; 5;0CJO ;Jl(d-, p F J' cL..,.-'.=. 5 ~ (;Yoo -:? / rtZ,, ✓ J /; ✓ (-; -7so y/- ) <",,,..., •..f10 -0, 4 / 9 CJO 77.o, v _, /-O,.tz: T ;,s ... ~ /.J; L:>Vt 7e.,, u 7o JD";, z 8 3 fl? ,. ,. 2- x: / z. ,c /~ ~ , ' Q ,,,-1 ;;;;-~ / ,,...,,c"? )('. 5 y / 2- )C / ,3. ~ /L~/-'.,'/~5 /4 G'~?--8~·-r - 4 -c,-r 5°' Cr?n-c;;,.>c - ~"'--,s ;' /./'I.,.,,, ✓ ~ "'1L /JJSPc,s,-,s Cc ~&-rs/--. i-v~ ,,'-( qco <- oc,-r- •;,; LJ «: ~,e,o,/ - 7£/ / - - ✓, ~,.G ~ t' )OO -/3Ch/ . • . C),,..J t:,..._,?. ~s "7? .)(/ -0.,...-e:. ~~r. T>m1,~ --<--. ~$r ', 1 ,·? J y ~ /tf. tr--0 ro.. A Jz.&.o If/. IJO '1.i,,,,{ • /tJ.oo /'J.-6-C)O 3, Cf I 00 tJ(tt':ll' 5! 00 ,, .:2,..S~ .56',oo ·' .5t' ro ')..&,/, 00 ,, ~)-1, (co ,. -

Volcanic Vistas Discover National Forests in Central Oregon Summer 2009 Celebrating the Re-Opening of Lava Lands Visitor Center Inside

Volcanic Vistas Discover National Forests in Central Oregon Summer 2009 Celebrating the re-opening of Lava Lands Visitor Center Inside.... Be Safe! 2 LAWRENCE A. CHITWOOD Go To Special Places 3 EXHIBIT HALL Lava Lands Visitor Center 4-5 DEDICATED MAY 30, 2009 Experience Today 6 For a Better Tomorrow 7 The Exhibit Hall at Lava Lands Visitor Center is dedicated in memory of Explore Newberry Volcano 8-9 Larry Chitwood with deep gratitude for his significant contributions enlightening many students of the landscape now and in the future. Forest Restoration 10 Discover the Natural World 11-13 Lawrence A. Chitwood Discovery in the Kids Corner 14 (August 4, 1942 - January 4, 2008) Take the Road Less Traveled 15 Larry was a geologist for the Deschutes National Forest from 1972 until his Get High on Nature 16 retirement in June 2007. Larry was deeply involved in the creation of Newberry National Volcanic Monument and with the exhibits dedicated in 2009 at Lava Lands What's Your Interest? Visitor Center. He was well known throughout the The Deschutes and Ochoco National Forests are a recre- geologic and scientific communities for his enthusiastic support for those wishing ation haven. There are 2.5 million acres of forest including to learn more about Central Oregon. seven wilderness areas comprising 200,000 acres, six rivers, Larry was a gifted storyteller and an ever- 157 lakes and reservoirs, approximately 1,600 miles of trails, flowing source of knowledge. Lava Lands Visitor Center and the unique landscape of Newberry National Volcanic Monument. Explore snow- capped mountains or splash through whitewater rapids; there is something for everyone. -

Metolius River Subbasin Fish Management Plan

METOLIUS RIVER SUBBASIN FISH MANAGEMENT PLAN UPPER DESCHUTES FISH DISTRICT December 1996 Principal Authors: Ted Fies Brenda Lewis Mark Manion Steve Marx ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The principal authors wish to acknowledge the help, encouragement, comments, and edits contributed by a large number of people including the Technical and Public Advisory Committees, ODFW Fish Division and Habitat Conservation Division staffs, Central Region staffs, other basin planners, district biologists, and staff from other agencies helped answer questions throughout the development of the plan. We especially want to thank members of the public who contributed excellent comments and management direction. We would also like to thank our families and friends who supported us during the five years of completing this task. i TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword iii Map of the Metolius River Subbasin 1 Introduction 2 METOLIUS RIVER AND TRIBUTARIES INCLUDING LAKE CREEK 4 Current Land Classification and Management 4 Access 5 Habitat and Habitat Limitations 6 Fish Resources 11 Fish Stocking History 17 Angling Regulations 19 Fishery 20 Fish Management 21 Management Issues 29 Management Direction 30 SUTTLE AND BLUE LAKES SUBBASIN 41 Suttle and Blue Lakes, and Link Creek 41 Location and Ownership 41 Habitat and Habitat Limitations 42 Fish Stocking History 45 Angling Regulations 46 Fish Management 48 Management Issues 51 Management Direction 52 METOLIUS SUBBASIN HIGH LAKES 57 Overview, Location and Ownership 57 Access 57 Habitat and Habitat Limitations 57 Fish Management 58 Management Issues 61 Management Direction 61 APPENDICES 67 Appendix A: References 67 Appendix B: Glossary 71 Appendix C: Oregon Administrative Rules 77 ii FOREWORD The Fish Management Policy of the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) requires that management plans be prepared for each basin or management unit. -

2021.06.11 BBR Resort Map Ktk.Indd

Fire Dept.non–emergency: 541-693-6911 | 911 | 541-693-6911 Dept.non–emergency: Fire . 13511 Hawks Beard, near Bishop’s Cap Cap Bishop’s near Beard, Hawks 13511 ROCK CLIMBING helicopters transport from the Sports Field. Field. Sports the from transport helicopters EXPLORE THE make up the Ranch. Ranch. the up make First Ascent Climbing o¡ers specialized climbing and has a fully-equipped fi rst aid room. Medical Medical room. aid rst fi fully-equipped a has and ums and various cabin clusters. About 1,200 homesites homesites 1,200 About clusters. cabin various and ums ADVENTURES services at Smith Rock State Park for all abilities. The BBR Fire Dept. is sta¡ ed with paramedics 24/7 24/7 paramedics with ed sta¡ is Dept. Fire BBR The Meadow (south). There also are three sets of condomini- of sets three are also There (south). Meadow BBR recommends helmets for all riders. all for helmets recommends BBR 1-866-climb11 | GoClimbing.com Home, South Meadow and Rock Ridge (center), and Glaze Glaze and (center), Ridge Rock and Meadow South Home, FIRST AID AID FIRST BACKYARD WITH OUTFITTERS when operating a bicycle, Razor, or inline skates. skates. inline or Razor, bicycle, a operating when into sections: Golf Home (NW), East Meadow (NE), Spring Spring (NE), Meadow East (NW), Home Golf sections: into BLACK BUTTE LOOKOUT • Anyone under 16 needs to wear a HELMET HELMET a wear to needs 16 under Anyone • for such a large residential resort. The Ranch is divided divided is Ranch The resort. residential large a such for FLY FISHING Police non–emergency: 541-693-6911 | 911 | 541-693-6911 non–emergency: Police Ranch Homeowners’ Association, a unique arrangement arrangement unique a Association, Homeowners’ Ranch Hike BBR’s namesake in this 3.6 mile, 1,556 foot climb. -

Sisters Area Trails System

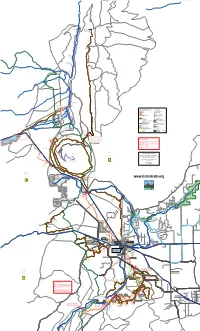

d a o r h g u o r p e e t s : N O I T U A C F S 1 4 9 0 40 11 FS !Z Prairie Farm : : Guard Station 0 G 1490-900 27 1 0 T S G F 9 H Lower Bridge 4 ! 1 Green Ridge Trail S F ends at junction with spur road FS 1490900 ")12 0 4 1 1 S F E G D I R FS 1154 1140-600 !Z F Green Ridge S 14 1 ")12 0 ") 1 7 Lookout 5 2 0 1 S F Wizard Falls Fish Hatchery !Z N E E R G West Metolius River Trail Metoliu s Windigo Trail 1 420 -40 Lower ek 0 Canyon Cre Canyon Creek Campground !9T !H k ee Cr ck Ja 0 2 ")12 4 1 S F F S 1 1 5 0 F S 1 2 3 0 FS 1425 ek re t C Firs ")11 ")12 ")14 F S 1 1 r 2 e 0 v i / R A l s l i n u i g l h o a t m e Metolius River Trail C M u l t i o (hiking only) a f f r R T d Lake Creek Trail e Camp g d Continues 4.3 miles Sherman i to Suttle Lake R 17 2 Store n 1 e S F e· e r G Mountain bike/pedestrian trail e· Information T !H Easy !G Bike store/services Moderate !Ê Horse camp T 16 Difficult !H Trailhead, Multi-Use 12 FS T d H R Old PRT Trail (easy) ! Trailhead, Hiking Only n a m !9 Campground r e ) h S es Horse trail !Z Place of interest i l p m m (4.3 a C Proposed trail Sisters Ranger District k Trail !@ ree k e C ake Cree â â â â Route from Village Green to PRT Shared road (gravel-cinder) Lak North Fork L Metolius Windigo Trail Road reek Middle Fork Lake C (Oregon State Scenic Trail, Unimproved road (not all primarily a horse trail) roads are shown on map) Hiking only Highway Head of the Whychus Draw Trail Creek Scenic bikeway Fork Lake ")11 th G Sou Metolius Trail Whychus Overlook Loop Trail (hiking only) City of Sisters !( 1 Junction number Deschutes Land Trust preserve ")14 Upper k ")12 Viewpoint (Hiking Only) Butte T G T Loop H !H ! FS 1430 Connector " Lodge T !H Upper Butte Loop Parking for the Green Ridge Trail is available at the trail crossing on FS 1120 / F S Allingham Cutoff Rd. -

Field Guides

Downloaded from fieldguides.gsapubs.org on August 1, 2011 Field Guides Fire and water: Volcanology, geomorphology, and hydrogeology of the Cascade Range, central Oregon Katharine V. Cashman, Natalia I. Deligne, Marshall W. Gannett, Gordon E. Grant and Anne Jefferson Field Guides 2009;15;539-582 doi: 10.1130/2009.fld015(26) Email alerting services click www.gsapubs.org/cgi/alerts to receive free e-mail alerts when new articles cite this article Subscribe click www.gsapubs.org/subscriptions/ to subscribe to Field Guides Permission request click http://www.geosociety.org/pubs/copyrt.htm#gsa to contact GSA Copyright not claimed on content prepared wholly by U.S. government employees within scope of their employment. Individual scientists are hereby granted permission, without fees or further requests to GSA, to use a single figure, a single table, and/or a brief paragraph of text in subsequent works and to make unlimited copies of items in GSA's journals for noncommercial use in classrooms to further education and science. This file may not be posted to any Web site, but authors may post the abstracts only of their articles on their own or their organization's Web site providing the posting includes a reference to the article's full citation. GSA provides this and other forums for the presentation of diverse opinions and positions by scientists worldwide, regardless of their race, citizenship, gender, religion, or political viewpoint. Opinions presented in this publication do not reflect official positions of the Society. Notes © 2009 Geological Society of America Downloaded from fieldguides.gsapubs.org on August 1, 2011 The Geological Society of America Field Guide 15 2009 Fire and water: Volcanology, geomorphology, and hydrogeology of the Cascade Range, central Oregon Katharine V. -

Metolius River by Bart Wills the Metolius River Is a Spring-Dominated Tributary of the Deschutes River in Central Oregon

Metolius River By Bart Wills The Metolius River is a spring-dominated tributary of the Deschutes River in central Oregon. The river is named for the Warm Springs Sahaptin word for "white fish," which refers to a light-colored Chinook salmon. The river is a sacred place for the Wasco, Warm Springs, and Northern Paiute of the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs, who have hunted, gathered, and fished from the river for thousands of years. The vibrant, crystalline, turquoise water of the twenty-nine-mile-long Metolius flows north from the base of Black Butte, passing the small community of Camp Sherman and eleven Forest Service campgrounds. After it passes Candle Creek, the river begins a relatively secluded journey, hooking east around Castle Rock, a nine-million-year-old volcanic plug, on the south and the Warm Springs Reservation to the north. The Metolius then flows southeast into Lake Billy Chinook, a reservoir, where it joins the Deschutes and Crooked Rivers. The portion of the Cascade Range immediately west of the Metolius valley is mostly younger than one million years—geologically young compared to the rest of the range. The moderate fault scarp, known as Green Ridge, has only 2,000 feet of vertical relief above the valley, with the rock at the top of the ridge preserving the geologic history of a slow collapse of volcanic lava flows five million years ago. Volcanic activity remained constant through time and continued to form new volcanoes, whose lava flows slowly filled the deep valley. Every hundred thousand years or so, the mountains were covered in hundreds of feet of ice, and glaciers ground down the volcanoes and deposited their remains in the valley as sediments of sand, gravel, and boulders. -

Winter Trail Guide

SISTERS AREA CHAMBER OF COMMERCE SISTERS WINTERAREA CHAMBER OF COMMERCE TRAIL GUIDE Sisters Area Chamber of Commerce www.thesisterscountry.com Special thanks to EST SERVI FOR CE D E E P U S R A U R TMENT OF AGRICU L T DAY USE OF USFS TRAILS Always use good judgement when using or traveling over trails and roads. Some are not maintained and may be hazardous. Weather and other conditions can change without notice, so carry clothing for rain and cold temperatures. Always carry adequate water for all hikes and never drink trailside water from lakes and streams unless marked “potable” by the Forest Service. Food, matches, first-aid kit, flashlight, compass and maps are also essential. Deschutes and Willamette National Forest Maps, the McKenzie River National Recreation Trail Map , and the Three Sisters, Mt. Washington, and Mt. Jefferson Wilderness maps are available at Forest Service Stations. Mosquito repellent should also be carried along in late spring and summer months. As a safety precaution, always let someone know where you are going and when you expect to return. Dogs should be on a leash or controlled by voice command. Be sure to have appropriate parking and trail permits for specific destinations. The Sisters Area Chamber of Commerce and its members are not responsible for losses or injuries incurred when utilizing this information. Wilderness Areas and US Forest Service Land Uses Wilderness Areas have a delicate state of natural balance. Careless acts by people can upset this balance, resulting in destruction of the wilderness environment. The following practices will help preserve the wilderness for everyone’s enjoyment. -

Bend Doris Lake – Great Day Trip; 2.7 Mile Hike to Not Enough Time to Go Fishing? Think Again – If You Live in the Bend, Redmond, Prineville, Picturesque Lake

Getting off the beaten track Common Fish If you prefer getting away from the crowds, there are several nearby hike-in lakes that offer calm, quiet and good fishing. 50 places The following all are just a short hike away: to go fishing within Todd Lake – short .5 mile hike in; brook trout up to 15-inches. Rainbow trout Redband trout Brook trout Blow Lake – good hike-n-fish opportunity for kids; 90 minutes swimming in July and Aug. of Bend Doris Lake – great day trip; 2.7 mile hike to Not enough time to go fishing? Think again – if you live in the Bend, Redmond, Prineville, picturesque lake. Sisters or LaPine areas there are a number of great fishing spots just a short drive away. Make sure you Deer Lake – good early season fishing for brook and read the Oregon Sport Fishing Regulations, and why not grab a friend or family member to go with you? Brown trout Atlantic salmon cutthroat trout. Kokanee The times and distances listed are from Drake Park in Bend. Lucky Lake – abundant brook trout; moderate 1-2) Crane Prairie Reservoir, Sunriver – 6) East Davis Campground 1.3 mile hike. 39 mi., 70 min. Rosary Lakes – series of three hike-in lakes; lowest is Redband rainbow trout, hatchery rainbow trout, brook a 2.5 mile hike; all are easily fished with a spinning rod. trout, largemouth bass, kokanee 7) Sparks Lake, Bend – 25 mi., 36 min. Spectacular views and excellent boat fishing for Cutthroat trout, brook trout Square Lake – popular hike lake-in near Santiam Pass; Largemouth Bass Smallmouth Bass Bullhead trout and bass. -

Draft Deschutes River Subbasin Summary

Draft Deschutes River Subbasin Summary August 3, 2001 Prepared for the Northwest Power Planning Council Lead Writer Leslie Nelson Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Subbasin Team Leader Clair Kunkel Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife DRAFT: This document has not yet been reviewed or approved by the Northwest Power Planning Council Deschutes River Subbasin Summary i DRAFT Contributors Glen Ardt, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Gary Asbridge, Mt. Hood National Forest Susan Barnes, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Merlin Berg, Wy’East Resource Conservation and Development Jon Bowers, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Chris Brun, Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation Chris Carey, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Krista Coelsch, Sherman County Soil and Water Conservation District Cedric Cooney, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Rick Craiger, Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board Jim Eisner, Bureau of Land Management Ron Graves, Wasco County Soil and Water Conservation District Mary Hanson, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Brad Houslet, Deschutes National Forest, Crescent District Ray Johnson, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Keith Kohl, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Rick Kruger, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Clair Kunkel, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Bonnie Lamb, Oregon Department of Environmental Quality Barbara Lee, Upper Deschutes River Watershed Council Steve Marx, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Scott McCaulou, Deschutes Resources Conservancy Dave Nelson, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation Tom Nelson, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Jim Newton, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Brad Nye, Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation Mike O’Connell, Jefferson County Soil and Water Conservation District Doug Olson, U.S. -

Vol. 45, No. 12

OREGOM GEOLOGY published by the Oregon Department of Geology and Mineral Industries VOLUME 45, NUMBER 12 DECEMBER 1983 OREGON GEOLOGY OIL AND GAS NEWS (ISSN 0164-3304) VOLUME 45, NUMBER 12 DECEMBER 1983 Clackamas County RHExploration, Rose 1, located in sec. 20, T. 5 S., R. I E., Published monthly by the State of Oregon Department of Geology was abandoned as a dry hole on October 24, 1983. RH has given no and Mineral Industries (Volumes 1 through 40 were entitled The Ore indication that it plans to drill Rose 2, permit 242. Bin). Mist Gas Field Reichho1d Energy Corporation has drilled and suspended Governing Board Wilson 11-5. The total depth was 2,827 ft, and the suspension date Allen P. Stinchfield, Chairman. .. North Bend was October 14, 1983. Additional drilling will be carried out at Donald A. Haagensen . .. Portland Sidney R. Johnson ......................... Baker Mist later in the year. State Geologist . Donald A. Hull Douglas County Drilling has begun in Douglas County on the Hutchins and Deputy State Geologist ................ John D. Beaulieu Marrs Glory Hole 1 in sec. 10, T. 27 S., R. 7 W. The operator spudded the well on October 28, 1983, with a proposed total depth Publications Manager/Editor . .. Beverly F. Vogt of 4,500 ft and has plans for four additional wells in the immediate area. Associate Editor ................. Klaus K.E. Neuendorf Main Office: 1005 State Office Building, Portland 97201, phone Lane County (503) 229-5580. Leavitt Exploration and Drilling is preparing to spud its Maurice Brooks 1 well in sec. 34, T. 19 S., R.