Einstein on the Beach: a Global Analysis Chelsea M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2006 Fall Newsletter

THE ENVIROTECH NEWSLETTER Fall 2006 Volume 6, Number 2 Some Great Envirotech Films By Numerous Generous Envirotech Members Inside this issue: Editor’s Note: Last spring Jeffrey Stine made the good suggestion that it might be useful to begin compiling a list of films on envirotech subjects. The following list is the first install- ment in that project. Perhaps a dozen or so of you were kind enough of send in titles and Vegas Session Report 2 brief descriptions. My thanks to you all! But two Envirotechies—Lindy Biggs and Pat Mun- day—really outdid themselves by contributing long lists of films with richly detailed descrip- ET News 3 tions. Indeed, I did not have space to include all of Lindy’s good suggestions. But again following a suggestion from Jeffrey Stine, I propose to continue to compile and periodically Member news 4 publish further additions to this list in the future. So for those of you who perhaps did not have the time to send in your suggestions this go-around, keep the project in mind for the ASEH Sneak Preview 8 spring. Likewise, whenever you discover a new film of value, please take a few moments to send me an e-mail so I can include it in future editions of the newsletter and add it to the Position Available 9 master list. Note that for convenience and to maintain uniformity I have generally not included the names of individual contributors except where necessary to obtain the film. But I do Conferences & Calls 10 (Continued on page 13) Update on the Envirotech Book Project By Stephen Cutcliffe Important Dates: • December 1: Deadline Several years ago the Envirotech lected essays that would “challenge conven- for nominations for the special interest group began a very interest- tional thinking about the relationship be- Envirotech prize for ing list serve discussion on what constitutes tween technology and nature and about hu- best article—see page our human technological relationship with mankind’s relationship with both” in a way 5 the natural world. -

Cardiovascular and Other Outcomes Postintervention

CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE AND DIABETES Diabetes Care Volume 39, May 2016 709 Cardiovascular and Other ORIGIN Trial Investigators* Outcomes Postintervention With Insulin Glargine and Omega-3 Fatty Acids (ORIGINALE) Diabetes Care 2016;39:709–716 | DOI: 10.2337/dc15-1676 OBJECTIVE The Outcome Reduction With Initial Glargine Intervention (ORIGIN) trial reported neutral effects of insulin glargine on cardiovascular outcomes and cancers and reduced incident diabetes in high–cardiovascular risk adults with dysglycemia after 6.2 years of active treatment. Omega-3 fatty acids had neutral effects on cardiovascular outcomes. The ORIGIN and Legacy Effects (ORIGINALE) study mea- sured posttrial effects of these interventions during an additional 2.7 years. RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS Surviving ORIGIN participants attended up to two additional visits. The hazard of clinical outcomes during the entire follow-up period from randomization was calculated. RESULTS Of 12,537 participants randomized, posttrial data were analyzed for 4,718 originally allocated to insulin glargine (2,351) versus standard care (2,367), and 4,771 originally allocated to omega-3 fatty acid supplements (2,368) versus placebo (2,403). Posttrial, small differences in median HbA1c persisted (glargine 6.6% [49 mmol/mol], standard care 6.7% [50 mmol/mol], P = 0.025). From randomization to the end of posttrial follow-up, no differences were found between the glargine and standard care groups in myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular death (1,185 vs. 1,165 Corresponding author: Zubin Punthakee, zubin. events; hazard ratio 1.01 [95% CI 0.94–1.10]; P = 0.72); myocardial infarction, stroke, [email protected]. cardiovascular death, revascularization, or hospitalization for heart failure (1,958 vs. -

ED351261.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 351 261 SO 022 575 AUTHOR Farnbach, Beth Earley, Ed. TITLE The Bill of Rights Alive! INSTITUTION Temple Univ., Philadelphia, PA. School of Law. SPONS AGENCY Commission on the Bicentennial of the United States Constitution, Washington, DC. PUB DATE 92 CONTRACT 91-CB-CX-0054 NOTE 100p.; Funding also received from the Pennsylvania Trial Lawyers Association. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EARS PRICE MF01/PC04 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Civil Liberties; Constitutional History; *Constitutional Law; Elementary Secondary Education; *Law Related Education; Learning Activities; Social Studies; Teaching Methods; United States History IDENTIFIERS *Bill of Rights; *United States Constitution ABSTRACT This collection of lesson plans presents ideas for educators and persons in the law and justice communityto teach young people about the Bill of Rights. The lesson plansare: "Mindwalk: An Introduction to the Law or How the Bill of Rights AffectsOur Liver"; "Bill of Rights Bingo"; "The Classroom 'ConstitutionalConvention': Writing A Constitution for Your Class"; "Rewriting the Billof Rights in Everyday Language"; "If James Madison Had Been inCharge of the World"; "Ranking Your Rights and Freedoms"; "Photojournalismand the Bill of Rights"; "Freedom Challenge"; "Do God andCountry Mix? The Free Exercise Clause and the Flag Salute"; "Religionand Secular Purpose"; "A Mock Supreme Court Hearing: Lyngv. Northwest Indian Cemettry Protective Association"; "Away with the Manger";"Choose on Choice: Pennsylvania's School Choice Legislationand the Separation of Church and State"; "An Impartial Jury: Voir Direand the Bill of Rights"; "Do You Really Need a Lawyer? The SixthAmendment & the Right to Counsel"; "From Brown to Bakke: The 14thAmendment"; "Drawing on Your Rights"; and "Bill of RightsMock Trial." Each lesson contains the lesson title, an overview, gradelevel, goals, a list of materials, possibleuses of outside resources, procedures/activities, and reflectionson the lesson. -

Download the List of History Films and Videos (PDF)

Video List in Alphabetical Order Department of History # Title of Video Description Producer/Dir Year 532 1984 Who controls the past controls the future Istanb ul Int. 1984 Film 540 12 Years a Slave In 1841, Northup an accomplished, free citizen of New Dolby 2013 York, is kidnapped and sold into slavery. Stripped of his identity and deprived of dignity, Northup is ultimately purchased by ruthless plantation owner Edwin Epps and must find the strength to survive. Approx. 134 mins., color. 460 4 Months, 3 Weeks and Two college roommates have 24 hours to make the IFC Films 2 Days 235 500 Nations Story of America’s original inhabitants; filmed at actual TIG 2004 locations from jungles of Central American to the Productions Canadian Artic. Color; 372 mins. 166 Abraham Lincoln (2 This intimate portrait of Lincoln, using authentic stills of Simitar 1994 tapes) the time, will help in understanding the complexities of our Entertainment 16th President of the United States. (94 min.) 402 Abe Lincoln in Illinois “Handsome, dignified, human and moving. WB 2009 (DVD) 430 Afghan Star This timely and moving film follows the dramatic stories Zeitgest video 2009 of your young finalists—two men and two very brave women—as they hazard everything to become the nation’s favorite performer. By observing the Afghani people’s relationship to their pop culture. Afghan Star is the perfect window into a country’s tenuous, ongoing struggle for modernity. What Americans consider frivolous entertainment is downright revolutionary in this embattled part of the world. Approx. 88 min. Color with English subtitles 369 Africa 4 DVDs This epic series presents Africa through the eyes of its National 2001 Episode 1 Episode people, conveying the diversity and beauty of the land and Geographic 5 the compelling personal stories of the people who shape Episode 2 Episode its future. -

Does Judicial Independence Matter? a Study of the Determinants of Administrative Litigation in an Authoritarian Regime

The Peter A. Allard School of Law Allard Research Commons Faculty Publications Allard Faculty Publications 2017 Does Judicial Independence Matter? A Study of the Determinants of Administrative Litigation in an Authoritarian Regime Wei Cui Allard School of Law at the University of British Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.allard.ubc.ca/fac_pubs Part of the Litigation Commons, Rule of Law Commons, and the Tax Law Commons Citation Details Wei Cui, "Does Judicial Independence Matter? A Study of the Determinants of Administrative Litigation in an Authoritarian Regime" ([forthcoming in 2017]) 38:3 U Pa J Int'l L 941. This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Allard Faculty Publications at Allard Research Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Allard Research Commons. DOES JUDICIAL INDEPENDENCE MATTER? DOES JUDICIAL INDEPENDENCE MATTER? A STUDY OF THE DETERMINANTS OF ADMINISTRATIVE LITIGATION IN AN AUTHORITARIAN REGIME Wei Cui* Lawsuits against the government form a part of the regular functioning of legal systems in democratic countries, and responding to such lawsuits an unavoidable part of governance. However, in the context of authoritarian regimes, administrative litigation has been viewed as a distinctively valuable institution for promoting the rule of law and individual rights. Moreover, the judiciary is portrayed as the keystone to this institution and to the rule of law in general: the more powerful and competent is the judiciary, the more it is able to “constrain government” through judicial review. Through empirical and comparative analyses of over two decades of administrative litigation in China against one of the state’s essential branches, tax collection, I challenge the utility of this normative conception of administrative litigation. -

The College News 1993-9-28 Vol.15 No. 7 (Bryn Mawr, PA: Bryn Mawr College, 1993)

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Bryn Mawr College Publications, Special Bryn Mawr College News Collections, Digitized Books 1993 The olC lege News 1993-9-28 Vol.15 No. 7 Students of Bryn Mawr College Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/bmc_collegenews Custom Citation Students of Bryn Mawr College, The College News 1993-9-28 Vol.15 No. 7 (Bryn Mawr, PA: Bryn Mawr College, 1993). This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/bmc_collegenews/1449 For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 ' ■ ' M 111 n; » . THE COLLEGE NEWS VOLUME XV NUMBER 8 FOUNDED T 1914 BRYN MAWR COLLEGE SEPTEMBESEPTEMBER 28, 1993 Ex-East German leaders convicted ?S by Tamara RozcnUl ' Clinton calls on former presidents to support of the agreement that would promote NAFTA remove trade barriers between the US, Three former East-German leaders Canada and Mexico. President Clinton were convicted on charges of inciting the Moments after finalizing the Israel- signed three supplemental agreements killing of citizens who were fleeing to the PLO agreement, President Clinton re- to NAFTA while Canadian Prime Minis- West. ter Kim Campbell and Mexican Presi- Former defense minister Kessler was dent Salinas de Gortari signed them in Oma leader sentenced to seven and a half years in their respective countries. prison while his deputy Franz Streletz •World News • will serve five and a half. H. Albrecht, a Yeltsin ousted at Haverford local communist, received a sentence of cruited three former presidents to help four and a half years. -

Does Judicial Independence Matter? a Study of the Determinants of Administrative Litigation in an Authoritarian Regime

DOES JUDICIAL INDEPENDENCE MATTER? A STUDY OF THE DETERMINANTS OF ADMINISTRATIVE LITIGATION IN AN AUTHORITARIAN REGIME WEI CUI ABSTRACT Lawsuits against the government form a part of the regular functioning of legal systems in democratic countries, and respond- ing to such lawsuits constitutes an unavoidable part of governance. However, in the context of authoritarian regimes, administrative litigation has been viewed as a distinctively valuable institution for promoting the rule of law and individual rights. Moreover, the ju- diciary is portrayed as the keystone to this institution and to the rule of law in general: the more powerful and competent is the ju- diciary, the more it is able to “constrain government” through judi- cial review. Through empirical and comparative analyses of over two decades of administrative litigation in China against one of the state’s essential branches, tax collection, I challenge the utility of this normative conception of administrative litigation. Using con- ceptual tools that apply across legal systems and regulatory areas, I show that while litigant behavior as well as the regulatory envi- ronment offer useful explanations of litigation patterns such as case volume and the plaintiff win rate, the relevance of judicial Associate Professor, Allard School of Law, University of British Columbia. Author email: [email protected]. I am grateful to Eric Hou and Xiang Fangfang for excellent research assistance and to Zhiyuan Wang for assistance with statistical analysis. I have benefited from comments by Cheng Jie, Jiang Hao, Liu Yue, Pit- man Potter, Wang Yaxin, Wei Guoqing, and audiences at the Sydney Chapter of the Australian Branch of the International Fiscal Association, Northwestern Uni- versity Law School, the Canadian Law and Economics Association Annual Meet- ing in 2014, and the 2016 Annual Comparative Law Work-in-Progress Workshop at the University of Illinois Law School on earlier drafts. -

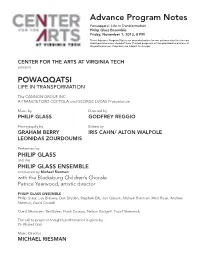

Advance Program Notes Powaqqatsi: Life in Transformation Philip Glass Ensemble Friday, November 1, 2013, 8 PM

Advance Program Notes Powaqqatsi: Life in Transformation Philip Glass Ensemble Friday, November 1, 2013, 8 PM These Advance Program Notes are provided online for our patrons who like to read about performances ahead of time. Printed programs will be provided to patrons at the performances. Programs are subject to change. CENTER FOR THE ARTS AT VIRGINIA TECH presents POWAQQATSI LIFE IN TRANSFORMATION The CANNON GROUP INC. A FRANCIS FORD COPPOLA and GEORGE LUCAS Presentation Music by Directed by PHILIP GLASS GODFREY REGGIO Photography by Edited by GRAHAM BERRY IRIS CAHN/ ALTON WALPOLE LEONIDAS ZOURDOUMIS Performed by PHILIP GLASS and the PHILIP GLASS ENSEMBLE conducted by Michael Riesman with the Blacksburg Children’s Chorale Patrice Yearwood, artistic director PHILIP GLASS ENSEMBLE Philip Glass, Lisa Bielawa, Dan Dryden, Stephen Erb, Jon Gibson, Michael Riesman, Mick Rossi, Andrew Sterman, David Crowell Guest Musicians: Ted Baker, Frank Cassara, Nelson Padgett, Yousif Sheronick The call to prayer in tonight’s performance is given by Dr. Khaled Gad Music Director MICHAEL RIESMAN Sound Design by Kurt Munkacsi Film Executive Producers MENAHEM GOLAN and YORAM GLOBUS Film Produced by MEL LAWRENCE, GODFREY REGGIO and LAWRENCE TAUB Production Management POMEGRANATE ARTS Linda Brumbach, Producer POWAQQATSI runs approximately 102 minutes and will be performed without intermission. SUBJECT TO CHANGE PO-WAQ-QA-TSI (from the Hopi language, powaq sorcerer + qatsi life) n. an entity, a way of life, that consumes the life forces of other beings in order to further its own life. POWAQQATSI is the second part of the Godfrey Reggio/Philip Glass QATSI TRILOGY. With a more global view than KOYAANISQATSI, Reggio and Glass’ first collaboration, POWAQQATSI, examines life on our planet, focusing on the negative transformation of land-based, human- scale societies into technologically driven, urban clones. -

EINSTEIN on the BEACH BROOKLYN ACADEMY of MUSIC Harvey Lichtenstein, President and Executive Producer

EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC Harvey Lichtenstein, President and Executive Producer presents in the BAM Opera House November 19-23; 1992; 7PM EINSTEIN ON THE BEACH An Opera in Four Acts by Philip Glass Robert Wilson Choreography by Lucinda Childs with Lucinda Childs Sheryl Sutton Gregory Fulkerson Lighting Design Musical Direction Sound Design Beverly Emmons/Robert Wilson Michael Riesman Kurt Munkacsi Spoken Text Christopher Knowles/Samuel M. Johnson/Lucinda Childs with The Lucinda Childs Dance Company Music Performed by the I I Philip Glass Ensemble Design/Direction Music/Lyrics Robert Wilson Philip Glass Producer Jedediah Wheeler Einstein on the Beach is a production of Top Shows, Inc. These performances of Einstein on the Beach are dedicated to the memory of Eric Benson, Ethyl Eichelberger, Michel Guy, Samuel M. Johnson and Robert LoBianco, who were an important part of this work. This presentation has been made possible, in part, by grants from Robert W. Wilson, The Fan Fox and Leslie R. Samuels Foundation, The Bohen Foundation, and The Mary Flagler Cary Charitable Trust. THE COMPANY (in alphabetical' order) Marion Beckenstein soprano, rear stenographer (trial/prison) soloist (train, dance 1, night train, dance 2) Lisa Bielawa soprano, front stenographer (trial/prison), soloist (train, dance 1, night train, dance 2) Susan Blankensop* dancer, woman in perpendicular dance (train) Janet Charleston* dan€er, woman reading,itrial, building), prisoner 2 (trial, prison) Lucinda Childs featured dancer/performer, character -

Summary of SC91368, State of Missouri V

Summary of SC91368, State of Missouri v. Melvin Ray Davis Appeal from the Greene County circuit court, Judge Jason R. Brown Argued and submitted May 4, 2011; opinion issued Aug. 30, 2011 Attorneys: The state was represented by Daniel N. McPherson of the attorney general’s office in Jefferson City, (573) 751-3321; and Davis was represented by Ruth K. Russell of the public defender’s office in Springfield, (417) 895-6740. This summary is not part of the opinion of the Court. It has been prepared by the communications counsel for the convenience of the reader. It neither has been reviewed nor approved by the Supreme Court and should not be quoted or cited. Overview: The state filed a criminal complaint against a registered sex offender for violating a statute making it a crime for a registered sex offender knowingly to be within 500 feet of a public park that contains playground equipment and a public swimming pool. The trial court dismissed the complaint on the ground that the statute was unconstitutionally retrospective in operation as applied to the defendant, and the state appeals. In a unanimous decision written by Judge Patricia Breckenridge, the Supreme Court of Missouri affirms the dismissal. The state failed to raise in the trial court its assertion that the trial court erred in finding the statute unconstitutional because the prohibition against retrospective laws applies only to civil statutes and the statute in question here is criminal, not civil, in nature. As such, the state failed to preserve this issue for appeal. Facts: Melvin Davis pleaded guilty in May 1983 to one count of sexual abuse. -

Philip Glass

DEBARTOLO PERFORMING ARTS CENTER PRESENTING SERIES PRESENTS MUSIC BY PHILIP GLASS IN A PERFORMANCE OF AN EVENING OF CHAMBER MUSIC WITH PHILIP GLASS TIM FAIN AND THIRD COAST PERCUSSION MARCH 30, 2019 AT 7:30 P.M. LEIGHTON CONCERT HALL Made possible by the Teddy Ebersol Endowment for Excellence in the Performing Arts and the Gaye A. and Steven C. Francis Endowment for Excellence in Creativity. PROGRAM: (subject to change) PART I Etudes 1 & 2 (1994) Composed and Performed by Philip Glass π There were a number of special events and commissions that facilitated the composition of The Etudes by Philip Glass. The original set of six was composed for Dennis Russell Davies on the occasion of his 50th birthday in 1994. Chaconnes I & II from Partita for Solo Violin (2011) Composed by Philip Glass Performed by Tim Fain π I met Tim Fain during the tour of “The Book of Longing,” an evening based on the poetry of Leonard Cohen. In that work, all of the instrumentalists had solo parts. Shortly after that tour, Tim asked me to compose some solo violin music for him. I quickly agreed. Having been very impressed by his ability and interpretation of my work, I decided on a seven-movement piece. I thought of it as a Partita, the name inspired by the solo clavier and solo violin music of Bach. The music of that time included dance-like movements, often a chaconne, which represented the compositional practice. What inspired me about these pieces was that they allowed the composer to present a variety of music composed within an overall structure. -

Films Shown by Series

Films Shown by Series: Fall 1999 - Winter 2006 Winter 2006 Cine Brazil 2000s The Man Who Copied Children’s Classics Matinees City of God Mary Poppins Olga Babe Bus 174 The Great Muppet Caper Possible Loves The Lady and the Tramp Carandiru Wallace and Gromit in The Curse of the God is Brazilian Were-Rabbit Madam Satan Hans Staden The Overlooked Ford Central Station Up the River The Whole Town’s Talking Fosse Pilgrimage Kiss Me Kate Judge Priest / The Sun Shines Bright The A!airs of Dobie Gillis The Fugitive White Christmas Wagon Master My Sister Eileen The Wings of Eagles The Pajama Game Cheyenne Autumn How to Succeed in Business Without Really Seven Women Trying Sweet Charity Labor, Globalization, and the New Econ- Cabaret omy: Recent Films The Little Prince Bread and Roses All That Jazz The Corporation Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room Shaolin Chop Sockey!! Human Resources Enter the Dragon Life and Debt Shaolin Temple The Take Blazing Temple Blind Shaft The 36th Chamber of Shaolin The Devil’s Miner / The Yes Men Shao Lin Tzu Darwin’s Nightmare Martial Arts of Shaolin Iron Monkey Erich von Stroheim Fong Sai Yuk The Unbeliever Shaolin Soccer Blind Husbands Shaolin vs. Evil Dead Foolish Wives Merry-Go-Round Fall 2005 Greed The Merry Widow From the Trenches: The Everyday Soldier The Wedding March All Quiet on the Western Front The Great Gabbo Fires on the Plain (Nobi) Queen Kelly The Big Red One: The Reconstruction Five Graves to Cairo Das Boot Taegukgi Hwinalrmyeo: The Brotherhood of War Platoon Jean-Luc Godard (JLG): The Early Films,