The Past Meets the Present

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 94, 1974-1975

BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Founded in 1881 by HENRY LEE HIGGINSON SEIJI OZAWA Music Director COLIN DAVIS Principal Guest Conductor NINETY- FOURTH SEASON 1974-1975 THE TRUSTEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. TALCOTT M. BANKS President PHILIP K.ALLEN SIDNEY STONEMAN JOHN L. THORNDIKE Vice-President Vice-President Treasurer VERNON R. ALDEN ARCHIE C. EPPS III JOHN T. NOONAN ALLEN G. BARRY MRS HARRIS FAHNESTOCK MRS JAMES H. PERKINS MRS JOHN M. BRADLEY HAROLD D. HODGKINSON IRVING W. RABB RICHARD P. CHAPMAN E.MORTON JENNINGS JR PAULC. REARDON ABRAM T. COLLIER EDWARD M. KENNEDY MRS GEORGE LEE SARGENT NELSON J. DARLING JR EDWARD G. MURRAY JOHN HOYT STOOKEY TRUSTEES EMERITUS FRANCIS W. HATCH PALFREY PERKINS HENRY A. LAUGHLIN ADMINISTRATION OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA THOMAS D. PERRY JR THOMAS W. MORRIS Executive Director Manager PAUL BRONSTEIN JOHN H. CURTIS MARY H. SMITH Business Manager Public Relations Director Assistant to the Manager FORRESTER C. SMITH DANIEL R. GUSTIN RICHARD C. WHITE Development Director Administrator of Assistant to Educational Affairs the Manager DONALD W. MACKENZIE JAMES F. KILEY Operations Manager, Operations Manager, Symphony Hall Tanglewood ELEANOR R. JONES Program Editor Copyright © 1974 by Boston Symphony Orchestra Inc. December SYMPHONY HALL BOSTON MASSACHUSETTS J 6 e 2 2 Meet Him In a Cloud of Chiffon Li Surely, he'll appreciate this graceful flow of gray / chiffon. Sc'oop necked and softly tiered skirted. • Ready to rise to an occasion. From our outstanding /Collection of long and short evening looks, ay or navy polyester chiffon. Misses sizes. $100 isses Dresses, in Boston and in Chestnut Hill Boston, Chestnut Hill, South \Shore, Northshore, Burlington, Wellesley BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA SEIJI OZAWA Music Director COLIN DAVIS Principal Guest Conductor NINETY-FOURTH SEASON 1974-1975 THE BOARD OF OVERSEERS OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA INC. -

The Sleeping Beauty Untouchable Swan Lake In

THE ROYAL BALLET Director KEVIN O’HARE CBE Founder DAME NINETTE DE VALOIS OM CH DBE Founder Choreographer SIR FREDERICK ASHTON OM CH CBE Founder Music Director CONSTANT LAMBERT Prima Ballerina Assoluta DAME MARGOT FONTEYN DBE THE ROYAL BALLET: BACK ON STAGE Conductor JONATHAN LO ELITE SYNCOPATIONS Piano Conductor ROBERT CLARK ORCHESTRA OF THE ROYAL OPERA HOUSE Concert Master VASKO VASSILEV Introduced by ANITA RANI FRIDAY 9 OCTOBER 2020 This performance is dedicated to the late Ian Taylor, former Chair of the Board of Trustees, in grateful recognition of his exceptional service and philanthropy. Generous philanthropic support from AUD JEBSEN THE SLEEPING BEAUTY OVERTURE Music PYOTR IL’YICH TCHAIKOVSKY ORCHESTRA OF THE ROYAL OPERA HOUSE UNTOUCHABLE EXCERPT Choreography HOFESH SHECHTER Music HOFESH SHECHTER and NELL CATCHPOLE Dancers LUCA ACRI, MICA BRADBURY, ANNETTE BUVOLI, HARRY CHURCHES, ASHLEY DEAN, LEO DIXON, TÉO DUBREUIL, BENJAMIN ELLA, ISABELLA GASPARINI, HANNAH GRENNELL, JAMES HAY, JOSHUA JUNKER, PAUL KAY, ISABEL LUBACH, KRISTEN MCNALLY, AIDEN O’BRIEN, ROMANY PAJDAK, CALVIN RICHARDSON, FRANCISCO SERRANO and DAVID YUDES SWAN LAKE ACT II PAS DE DEUX Choreography LEV IVANOV Music PYOTR IL’YICH TCHAIKOVSKY Costume designer JOHN MACFARLANE ODETTE AKANE TAKADA PRINCE SIEGFRIED FEDERICO BONELLI IN OUR WISHES Choreography CATHY MARSTON Music SERGEY RACHMANINOFF Costume designer ROKSANDA Dancers FUMI KANEKO and REECE CLARKE Solo piano KATE SHIPWAY JEWELS ‘DIAMONDS’ PAS DE DEUX Choreography GEORGE BALANCHINE Music PYOTR IL’YICH TCHAIKOVSKY -

Liebeslieder-Walzer Et Lieder Choisis Johannes Brahms

Roch-Olivier Maistre, Président du Conseil d’administration Laurent Bayle, Directeur général Jeudi 5 février Johannes Brahms | Liebeslieder-Walzer et lieder choisis Jeudi 5 février | Dans le cadre du cycle Le temps de la danse Du samedi 31 janvier au vendredi 6 février 2009 et lieder choisis Liebeslieder-Walzer Liebeslieder-Walzer Vous avez la possibilité de consulter les notes de programme en ligne, 2 jours avant chaque concert, à l’adresse suivante : www.citedelamusique.fr Johannes Brahms | Johannes Brahms Cycle Le temps de la danse La valse, la bourrée… : toutes les danses dictent leur rythme. Elles donnent le ton et le temps à ceux qui s’y accordent. De la danse traditionnelle thaïe aux Ländler de Brahms, les pulsations d’une chorégraphie réelle ou rêvée emportent la musique et les corps dans leurs tournoiements. Le khon, théâtre traditionnel thaï apparu voici mille ans dans les cours royales d’Ayutthaya, s’imposa rapidement comme le divertissement privilégié des rois. Il met en scène des personnages masqués, richement costumés de brocarts de soie, qui exécutent des danses très codifiées, accompagnées par des musiciens, des chanteurs et des narrateurs. La très forte puissance évocatrice de cet art pictural vivant permet d’entrer en contact avec le monde invisible, de donner âme aux croyances magiques… Et aussi de fonder l’identité de la communauté, de la rassembler sur des temps forts. Le programme imaginé par Jordi Savall sous le titre de Ludi Musici : L’esprit de la danse participe du même paradoxe, pas dansés qui font à la fois la distinction et la communion des corps : il présente un répertoire composite, qui rassemble deux siècles de musiques dansées (de 1450 à 1650) en Europe occidentale, en Asie occidentale et en Amérique latine. -

Arthur Kleiner, Who Has Been Composing, Arranging and Playing the Piano Accompani

he Museum of Modern Art i^ No. 32 |l West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Circle 5-8900 Cable: Modernart FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Tuesday, March 28, 1967 Arthur Kleiner, who has been composing, arranging and playing the piano accompani ments for silent films at The Museum of Modern Art for 28 years, is retiring the first of April, Rene d'Hamonoourt. Director of the Museum, announced today. As Music Director of the Department of Film since 1939, and probably the world's only full- time silent movie pianist, Mr. Kleiner has sought out long-lost scores for innumerable early films, researched films for which the scores could not be found in order to com pose the appropriate music, and written scores when none existed. Born in Vienna, Austria, Mr. Kleiner studied piano, organ and theory at the Vienna Music Academy from 191ii to 1921. From then until 1928 he was an accompanist- composer for major dance companies touring throughout Europe and a professor at Max Reinhardt's Seminar for Actors in Vienna, where he also composed scores for numerous plays. He conducted A Midsummer Night's Dream for Reinhardt during the Salzburg Festival of 1933- After arriving in the United States in 1938, his first job was playing piano accompaniment for choreographer George Balanchine, as well as for Agnes de Mille and the Ballet Theatre. In 1939 when he was approached by Iris Barry, first Curator of the Museum's Department of Film, to play for the Museum's screenings, she asked him if he could play ragtime. -

Playbill Jan

UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS AMHERST FINE ARTS CENTER 2012 Center Series Playbill Jan. 31 - Feb. 22 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Skill.Smarts.Hardwork. That’s how you built your wealth. And that’s how we’ll manage it. The United Wealth Management Group is an independent team of skilled professionals with a single mission: to help their clients fulfill their financial goals. They understand the issues you face – and they can provide tailored solutions to meet your needs. To arrange a confidential discussion, contact Steven Daury, CerTifieD fiNANCiAl PlANNer™ Professional, today at 413-585-5100. 140 Main Street, Suite 400 • Northampton, MA 01060 413-585-5100 unitedwealthmanagementgroup.com tSecurities and Investment Advisory Services offered through NFP Securities, Inc., Member FINRA/SIPC. NFP Securities, Inc. is not affiliated with United Wealth Management Group. NOT FDIC INSURED • MAY LOSE VALUE • NOT A DEPOSIT• NO BANK GUARANTEE NO FEDERAL GOVERNMENT AGENCY GUARANTEES 10 4.875" x 3.75" UMASS FAC Playbill Skill.Smarts.Hardwork. That’s how you built your wealth. And that’s how we’ll manage it. The United Wealth Management Group is an independent team of skilled professionals with a single mission: to help their clients fulfill their financial goals. They understand the issues you face – and they can provide tailored solutions to meet your needs. To arrange a confidential discussion, contact Steven Daury, CerTifieD fiNANCiAl PlANNer™ Professional, today at 413-585-5100. 140 Main Street, Suite 400 • Northampton, MA 01060 413-585-5100 unitedwealthmanagementgroup.com tSecurities and Investment Advisory Services offered through NFP Securities, Inc., Member FINRA/SIPC. -

Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center

Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center Saturday, April 18, 2015 8 p.m. 7:15 p.m. – Pre-performance discussion Regina A. Quick Center for the Arts www.quickcenter.com ~INTERMISSION~ COPLAND ................................ Two Pieces for Violin and Piano (1926) K. LEE, MCDERMOTT ANNE-MARIE MCDERMOTT, piano STRAVINSKY ................................Concertino for String Quartet (1920) DAVID SHIFRIN, clarinet AMPHION STRING QUARTET, HYUN, KRISTIN LEE, violin SOUTHORN, LIN, MARICA AMPHION STRING QUARTET KATIE HYUN, violin DAVID SOUTHORN, violin COPLAND ............................................Sextet for Clarinet, Two Violins, WEI-YANG ANDY LIN, viola Viola, Cello, and Piano (1937) MIHAI MARICA, cello Allegro vivace Lento Finale STRAVINSKY ..................................... Suite italienne for Cello and Piano SHIFRIN, HYUN, SOUTHORN, Introduzione: Allegro moderato LIN, MARICA, MCDERMOTT Serenata: Larghetto Aria: Allegro alla breve Tarantella: Vivace Please turn off cell phones, beepers, and other electronic devices. Menuetto e Finale Photographing, sound recording, or videotaping this performance is prohibited. MARICA, MCDERMOTT COPLAND ...............................Two Pieces for String Quartet (1923-28) AMPHION STRING QUARTET, HYUN, SOUTHORN, LIN, MARICA STRAVINSKY ............................Suite from Histoire du soldat for Violin, Clarinet, and Piano (1918-19) The Soldier’s March Music to Scene I Music to Scene II Tonight’s performance is sponsored, in part, by: The Royal March The Little Concert Three Dances: Tango–Waltz–Ragtime The Devil’s Dance Great Choral Triumphal March of the Devil K. LEE, SHIFRIN, MCDERMOTT Notes on the Program by DR. RICHARD E. RODDA Two Pieces for String Quartet Aaron Copland Suite italienne for Cello and Piano Born November 14, 1900 in Brooklyn, New York. Igor Stravinsky Died December 2, 1990 in North Tarrytown, New York. -

![Minna Lederman Daniel Collection [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7275/minna-lederman-daniel-collection-finding-aid-library-of-congress-1067275.webp)

Minna Lederman Daniel Collection [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress

Minna Lederman Daniel Collection Processed by the Music Division of the Library of Congress Music Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2009 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/perform.contact Catalog Record: http://lccn.loc.gov/2009543859 Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Music Division, 2009 Finding aid URL: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/eadmus.mu009006 Latest revision: 2010 March Collection Summary Title: Minna Lederman Daniel Collection Span Dates: 1896-1993 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1960-1990) Call No.: ML31.L43 Creator: Lederman, Minna Extent: circa 20,000 items ; 22 containers ; 11 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: The collection contains correspondence, financial and legal papers, writings, clippings, and photographs belonging to Minna Lederman Daniel, an editor and writer about music and dance, and a major influence on 20th century music. She was a founding member of the League of Composers, a group of musicians and proponents of modern music. She helped launch the League’s magazine, The League of Composers’ Review (later called Modern Music), which was the first American journal to manifest an interest in contemporary composers. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Cage, John--Correspondence. Cage, John. Carter, Elliott, 1908- --Correspondence. Copland, Aaron, 1900-1990--Correspondence. Copland, Aaron, 1900-1990. Cunningham, Merce--Correspondence. Denby, Edwin, 1903-1983--Correspondence. -

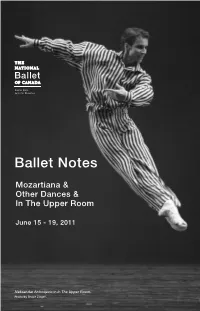

Ballet Notes

Ballet Notes Mozartiana & Other Dances & In The Upper Room June 15 - 19, 2011 Aleksandar Antonijevic in In The Upper Room. Photo by Bruce Zinger. Orchestra Violins Bassoons Benjamin BoWman Stephen Mosher, Principal Concertmaster JerrY Robinson LYnn KUo, EliZabeth GoWen, Assistant Concertmaster Contra Bassoon DominiqUe Laplante, Horns Principal Second Violin Celia Franca, C.C., Founder GarY Pattison, Principal James AYlesWorth Vincent Barbee Jennie Baccante George Crum, Music Director Emeritus Derek Conrod Csaba KocZó Scott WeVers Karen Kain, C.C. Kevin Garland Sheldon Grabke Artistic Director Executive Director Xiao Grabke Trumpets David Briskin Rex Harrington, O.C. NancY KershaW Richard Sandals, Principal Music Director and Artist-in-Residence Sonia Klimasko-LeheniUk Mark Dharmaratnam Principal Conductor YakoV Lerner Rob WeYmoUth Magdalena Popa Lindsay Fischer JaYne Maddison Trombones Principal Artistic Coach Artistic Director, Ron Mah DaVid Archer, Principal YOU dance / Ballet Master AYa MiYagaWa Robert FergUson WendY Rogers Peter Ottmann Mandy-Jayne DaVid Pell, Bass Trombone Filip TomoV Senior Ballet Master Richardson Tuba Senior Ballet Mistress Joanna ZabroWarna PaUl ZeVenhUiZen Sasha Johnson Aleksandar AntonijeVic, GUillaUme Côté*, Violas Harp Greta Hodgkinson, Jiˇrí Jelinek, LUcie Parent, Principal Zdenek KonValina, Heather Ogden, Angela RUdden, Principal Sonia RodrigUeZ, Piotr StancZYk, Xiao Nan YU, Theresa RUdolph KocZó, Timpany Bridgett Zehr Assistant Principal Michael PerrY, Principal Valerie KUinka Kevin D. Bowles, Lorna Geddes, -

The American Stravinsky

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY THE AMERICAN STRAVINSKY The Style and Aesthetics of Copland’s New American Music, the Early Works, 1921–1938 Gayle Murchison THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN PRESS :: ANN ARBOR TO THE MEMORY OF MY MOTHERS :: Beulah McQueen Murchison and Earnestine Arnette Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2012 All rights reserved This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publisher. Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America ϱ Printed on acid-free paper 2015 2014 2013 2012 4321 A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-472-09984-9 Publication of this book was supported by a grant from the H. Earle Johnson Fund of the Society for American Music. “Excellence in all endeavors” “Smile in the face of adversity . and never give up!” Acknowledgments Hoc opus, hic labor est. I stand on the shoulders of those who have come before. Over the past forty years family, friends, professors, teachers, colleagues, eminent scholars, students, and just plain folk have taught me much of what you read in these pages. And the Creator has given me the wherewithal to ex- ecute what is now before you. First, I could not have completed research without the assistance of the staff at various libraries. -

Convert Finding Aid To

Fred Fehl: A Preliminary Inventory of His Dance Collection at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Fehl, Fred, 1906-1995 Title: Fred Fehl Dance Collection 1940-1985 Dates: 1940-1985 Extent: 122 document boxes, 19 oversize boxes, 3 oversize folders (osf) (74.8 linear feet) Abstract: This collection consists of photographs, programs, and published materials related to Fehl's work documenting dance performances, mainly in New York City. The majority of the photographs are black and white 5 x 7" prints. The American Ballet Theatre, the Joffrey Ballet, and the New York City Ballet are well represented. There are also published materials that represent Fehl's dance photography as reproduced in newspapers, magazines and other media. Call Number: Performing Arts Collection PA-00030 Note: This brief collection description is a preliminary inventory. The collection is not fully processed or cataloged; no biographical sketch, descriptions of series, or indexes are available in this inventory. Access: Open for research. An advance appointment is required to view photographic negatives in the Reading Room. For selected dance companies, digital images with detailed item-level descriptions are available on the Ransom Center's Digital Collections website. Administrative Information Acquisition: Purchases and gift, 1980-1990 (R8923, G2125, R10965) Processed by: Sue Gertson, 2001; Helen Adair and Katie Causier, 2006; Daniela Lozano, 2012; Chelsea Weathers and Helen Baer, 2013 Repository: Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin Fehl, Fred, 1906-1995 Performing Arts Collection PA-00030 Scope and Contents Fred Fehl was born in 1906 in Vienna and lived there until he fled from the Nazis in 1938, arriving in New York in 1939. -

Sccopland on The

THE UNITED STATES ARMY FIELD BAND SOLDIERS’ CHORUS The Legacy of AARON COPLAND Washington, D.C. “The Musical Ambassadors of the Army” he Soldiers’ Chorus, founded in 1957, is the vocal complement of the T United States Army Field Band of Washington, DC. The 29-member mixed choral ensemble travels throughout the nation and abroad, performing as a separate component and in joint concerts with the Concert Band of the “Musical Ambassadors of the Army.” The chorus has performed in all fifty states, Canada, Mexico, India, the Far East, and throughout Europe, entertaining audiences of all ages. The musical backgrounds of Soldiers’ Chorus personnel range from opera and musical theatre to music education and vocal coaching; this diversity provides unique programming flexibility. In addition to pre- senting selections from the vast choral repertoire, Soldiers’ Chorus performances often include the music of Broadway, opera, barbershop quartet, and Americana. This versatility has earned the Soldiers’ Chorus an international reputation for presenting musical excellence and inspiring patriotism. Critics have acclaimed recent appearances with the Boston Pops, the Cincinnati Pops, and the Detroit, Dallas, and National symphony orchestras. Other no- table performances include four world fairs, American Choral Directors Association confer- ences, music educator conven- tions, Kennedy Center Honors Programs, the 750th anniversary of Berlin, and the rededication of the Statue of Liberty. The Legacy of AARON COPLAND About this Recording The Soldiers’ Chorus of the United States Army Field Band proudly presents the second in a series of recordings honoring the lives and music of individuals who have made significant contributions to the choral reper- toire and to music education. -

Music of New Orleans a Concert in Honor of Vivian Perlis

Music of New Orleans A Concert in Honor of Vivian Perlis Society for American Music 45th Annual Conference New Orleans, Louisiana 22 March 2019 George and Joyce Wein Jazz & Heritage Center 7:00 p.m. Sarah Jane McMahon, soprano Peter Collins, piano The Society for American Music is delighted to welcome you to the fourth Vivian Perlis Concert, a series of performances of music by contemporary American composers at the society’s annual conferences. We are grateful to the Virgil Thomson Foundation, the Aaron Copland Fund, and to members of the Society for their generous support. This concert series honors Vivian Perlis, whose publications, scholarly activities, and direction of the Oral History of American Music (OHAM) project at Yale University have made immeasurable contributions to our understanding of American composers and music cultures. In 2007 the Society for American Music awarded her the Lifetime Achievement Award for her remarkable achievements. The George and Joyce Wein Jazz & Heritage Center is an education and cultural center of the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Foundation, the nonprofit that owns the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival. It is a 12,000-square foot building that boasts seven music instruction classrooms for the Heritage School of Music, a recording studio, and a 200-seat auditorium. Additionally, a large collection of Louisiana art graces the walls of the center, creating an engaging environment for the educational and cultural activities in the building. The auditorium was designed by Oxford Acoustics. It can be adapted to multiple uses from concerts to theatrical productions to community forums and workshops. The room’s acoustics are diffusive and intimate, and it is equipped with high-definition projection, theatrical lighting and a full complement of backline equipment.