January/February 2000 Issue 7

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

YNERGY a Process of Becoming, of Creating and Transforming

V B W M SYNERGY a process of becoming, of creating and transforming VIRGINIA BAPTIST WOMEN IN MINISTRY VOL. 3, NO. 2 VBWIM Elects New VBWIM to Meet in Officers Salem Ellen Gwathmey was named the new Virginia Baptist Women in Ministry will convener of Virginia Baptist Women in meet for dinner on Tuesday evening, November Ministry, replacing Betty Pugh who has 15, in Salem in conjunction with the Virginia resigned to begin graduate school. Betty Pugh, Baptist General Association. The dinner will be who remains associate pastor at Grace Church held at Colonial Avenue Church. The program in Richmond, has been chair since 1992. again will be discussion around the table and The steering committee of VBWIM met in will focus on issues of interest to both men and June to evaluate the spring conference, to name women. Additional information will be avail- officers and to make plans for the coming able and publicized at a later date. months. New participants in the steering committee INSIDE were welcomed: Sonya Park-Taylor, represent- INSIDE ing the Baptist Center for Women at Baptist Spring Conference Held Ex Cathedra … 2 Theological Seminary at Richmond, and Ronda Stewart-Wilcox, minister of education at May About fifty people met in May at Ginter Park Editorial … 2 Memorial, Powhatan, and board member for the Church in Richmond to explore the topic “Full national Southern Baptist Women in Ministry. Partners: Women and Men in Ministry” at the Conference June Hardy Dorsey, minister of education at spring conference of Virginia Baptist Women in Highlights … 3 Ginter Park Church, Richmond, returned to the Ministry committee after a brief respite. -

The Eastern Star

Vol. 1. INDIANAPOLIS. INDIANA. JUNE. 1888. No. I. THE EASTERN STAR. women interested in the health and morals tion in behalf of something still better in of their families and of the community. dress, and various reform garments and sys Star of the Orient! Wc hail thee to-uight, Books, magazines and pamphlets refering tems have been devised with view to dis Gleaming in beauty, from Bethlehem Afar: Shine in our hearts with thy radiance bright, to these topics are to be found in almost pensing with whatever may interfere with Thou art our beacon-light, beautiful Star! every intelligent household; and a part of health and perfect physical development. Thou, by‘thy rising, dispelled the deep gloom. the regular work of the Woman’s Christian Of these, the “Jenness-Miller improved Which for long centuries darkened the grave, Temperance Union is the study of the rela dress,” though of recent inveution, has re Brought hope to mourning hearts, out of the tomb, tion between bad sanitary conditions and the ceived the most favorable consideration from Heralding Him who is mighty to save. drink problem. women, particularly society women. Star of the East, the night winds still linger Practice is the natural outgrowth of theory Gaining wisdom from the discouraging Dreamily over Juda's wild plains, and knowledge; with all the lamenting over experience of some of her predecessors, Where years gone by, the Angelic singers, Filled all the air with their heavenly strains. the degeneracy of u.odern times, the race is Mrs. Miller has sought to design dresses actually advancing in physical vigor. -

Marriage Record Index 1922-1938 Images Can Be Accessed in the Indiana Room

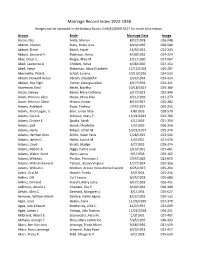

Marriage Record Index 1922-1938 Images can be accessed in the Indiana Room. Call (812)949-3527 for more information. Groom Bride Marriage Date Image Aaron, Elza Antle, Marion 8/12/1928 026-048 Abbott, Charles Ruby, Hallie June 8/19/1935 030-580 Abbott, Elmer Beach, Hazel 12/9/1922 022-243 Abbott, Leonard H. Robinson, Berta 4/30/1926 024-324 Abel, Oscar C. Ringle, Alice M. 1/11/1930 027-067 Abell, Lawrence A. Childers, Velva 4/28/1930 027-154 Abell, Steve Blakeman, Mary Elizabeth 12/12/1928 026-207 Abernathy, Pete B. Scholl, Lorena 10/15/1926 024-533 Abram, Howard Henry Abram, Elizabeth F. 3/24/1934 029-414 Absher, Roy Elgin Turner, Georgia Lillian 4/17/1926 024-311 Ackerman, Emil Becht, Martha 10/18/1927 025-380 Acton, Dewey Baker, Mary Cathrine 3/17/1923 022-340 Adam, Herman Glen Harpe, Mary Allia 4/11/1936 031-273 Adam, Herman Glenn Hinton, Esther 8/13/1927 025-282 Adams, Adelbert Pope, Thelma 7/14/1927 025-255 Adams, Ancil Logan, Jr. Eiler, Lillian Mae 4/8/1933 028-570 Adams, Cecil A. Johnson, Mary E. 12/21/1923 022-706 Adams, Crozier E. Sparks, Sarah 4/1/1936 031-250 Adams, Earl Snook, Charlotte 1/5/1935 030-250 Adams, Harry Meyer, Lillian M. 10/21/1927 025-376 Adams, Herman Glen Smith, Hazel Irene 2/28/1925 023-502 Adams, James O. Hallet, Louise M. 4/3/1931 027-476 Adams, Lloyd Kirsch, Madge 6/7/1932 028-274 Adams, Robert A. -

Documenting Women's Lives

Documenting Women’s Lives A Users Guide to Manuscripts at the Virginia Historical Society A Acree, Sallie Ann, Scrapbook, 1868–1885. 1 volume. Mss5:7Ac764:1. Sallie Anne Acree (1837–1873) kept this scrapbook while living at Forest Home in Bedford County; it contains newspaper clippings on religion, female decorum, poetry, and a few Civil War stories. Adams Family Papers, 1672–1792. 222 items. Mss1Ad198a. Microfilm reel C321. This collection of consists primarily of correspondence, 1762–1788, of Thomas Adams (1730–1788), a merchant in Richmond, Va., and London, Eng., who served in the U.S. Continental Congress during the American Revolution and later settled in Augusta County. Letters chiefly concern politics and mercantile affairs, including one, 1788, from Martha Miller of Rockbridge County discussing horses and the payment Adams's debt to her (section 6). Additional information on the debt appears in a letter, 1787, from Miller to Adams (Mss2M6163a1). There is also an undated letter from the wife of Adams's brother, Elizabeth (Griffin) Adams (1736–1800) of Richmond, regarding Thomas Adams's marriage to the widow Elizabeth (Fauntleroy) Turner Cocke (1736–1792) of Bremo in Henrico County (section 6). Papers of Elizabeth Cocke Adams, include a letter, 1791, to her son, William Cocke (1758–1835), about finances; a personal account, 1789– 1790, with her husband's executor, Thomas Massie; and inventories, 1792, of her estate in Amherst and Cumberland counties (section 11). Other legal and economic papers that feature women appear scattered throughout the collection; they include the wills, 1743 and 1744, of Sarah (Adams) Atkinson of London (section 3) and Ann Adams of Westham, Eng. -

The Lee Family and Freedom of the Press in Virginia the Free Press Clause in the First Amendment to the U.S

ROGER MELLEN The Lee Family and Freedom of the Press in Virginia The free press clause in the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution is considered a unique and important part of our American democracy. While the origins of this right are a key to current legal interpretations, there is much misunderstanding about its genesis. This research uses eighteenth-century personal correspondence, other archival evidence, and published articles to demonstrate new connections between the Lee family of Virginia and the constitutional right to a free press. The important tradition of freedom of the press in the United of Virginia led Madison to pledge proposing a bill of rights if States owes a greater debt to one important family in Virginia than he were elected to Congress.2 When he did join the new House has been previously recognized. When we reflect upon the origins of of Representatives, Madison did as promised and composed the the right to freedom of the press, we tend to remember John Locke, amendments. He had as his template objections voiced to the new John Milton, James Madison, or even Thomas Jefferson. Delving a Constitution by the state ratifying conventions and the bills of bit more deeply, we might even connect to George Mason and the rights passed by many of the states, including the groundbreaking Virginia Declaration of Rights—the first time press freedom was Declaration of Rights of Virginia.3 enshrined within a bill of rights. Looking at British political roots, In the years since the states ratified the First Amendment, we may even link the concept to Sir William Blackstone, Lord many historians and legal theorists have tried to determine Bolingbroke, Cato (John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon), or John its original intent, especially with regards to seditious libel (or Wilkes. -

Fitting Young Women for Upper-Class Virginia Society 1760--1810" (1982)

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1982 To be amiable and accomplished: Fitting young women for upper- class Virginia society 1760--1810 Tori Ann Eberlein College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, United States History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Eberlein, Tori Ann, "To be amiable and accomplished: Fitting young women for upper-class Virginia society 1760--1810" (1982). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625195. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-3w75-hz74 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TO BE AMIABLE AND ACCOMPLISHED: H FITTING YOUNG WOMEN FOR UPPER-CLASS VIRGINIA SOCIETY 1760 - 1810 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Tori Eberlein APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved April, 1982 __________ S&hw <A)CLlP£ James L. Axtell James P. Whittenburg Thad WJT^te For Keith With Special Thanks to Anne Blair TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT ...................... v INTRODUCTION . .............................. 3 CHAPTER I. RUDIMENTS OF A POLITE EDUCATION ... -

PLANTATION LIFE at GEORGE WASHINGTON's MOUNT VERNON, 1754 to 1799 by Gwendolyn K. White a Dissertation

COMMERCE AND COMMUNITY: PLANTATION LIFE AT GEORGE WASHINGTON’S MOUNT VERNON, 1754 TO 1799 by Gwendolyn K. White A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy History Committee: ___________________________________________ Director ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ __________________________________________ Department Chairperson ___________________________________________ Program Director ___________________________________________ Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: _____________________________________ Spring Semester 2016 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Commerce and Community: Plantation Life at George Washington’s Mount Vernon, 1754 to 1799 A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University by Gwendolyn K. White Master of Architectural History University of Virginia 2003 Bachelor of Individualized Studies George Mason University, 2000 Director: Cynthia A. Kierner, Professor Department of History Spring Semester 2016 George Mason University Fairfax, VA This work is licensed under a creative commons attribution-noderivs 3.0 unported license. ii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated in memory of my parents, Walter and Madelyn Berns, and my husband, Egon Verheyen. I wish you were here, but I feel your pride. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS -

Maryland Historical Magazine Is Published Quarterly by the Maryland Historical Society, 201 W

ARYLA Published Quarterly by the Maryland Historical Society SUMMER 1977 Vol. 72, No. 2 BOARD OF EDITORS JOSEPH L. ARNOLD, University of Maryland, Baltimore County JEAN BAKER, Goucher College GARY BROWNE, University of Maryland, Baltimore County GEORGE H. CALLCOTT, University of Maryland, College Park JOSEPH W. COX, Towson State University CURTIS CARROLL DAVIS, Baltimore RICHARD R. DUNCAN, Georgetown University RONALD HOFFMAN, University of Maryland, College Park EDWARD C. PAPENFUSE, Hall of Records BENJAMIN OUARLES, Morgan State University JOHN B. BOLES, Editor, Towson State University NANCY G. BOLES, Assistant Editor ELIZABETH M. DANIELS, Assistant Editor RICHARD J. COX, Manuscripts MARY K. MEYER, Genealogy MARY KATHLEEN THOMSEN, Graphics FORMER EDITORS WILLIAM HAND BROWNE, 1906-1909 LOUIS H. DIELMAN, 1910-1937 JAMES W. FOSTER, 1938-1949, 1950-1951 HARRY AMMON, 1950 FRED SHELLEY, 1951-1955 FRANCIS C. HABER, 1955-1958 RICHARD WALSH, 1958-1967 RICHARD R. DUNCAN, 1967-1974 P. WILLIAM FILBY, Director ROMAINE S. SOMERVILLE,>issisIanf Director-Curator of the Galley WALTER J. SKAYHAN, III, Assistant Director-Administration The Maryland Historical Magazine is published quarterly by the Maryland Historical Society, 201 W. Monument Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21201. Contributions and correspondence relating to articles, book reviews, and any other editorial matters should be addressed to the Editor in care of the Society. All contributions should be submitted in duplicate, double-spaced, and consistent with the form out- lined in A Manual of Style (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1969). The Maryland Historical Society disclaims responsibility for statements made by contributors. Composed and printed at Waverly Press, Inc., Baltimore, Maryland 21202. Second-class postage paid at Baltimore, Maryland. -

The Issue of Women's Voting Rights and Practice in Early America

The issue of women’s voting rights and practice in early America Linda Garbaye From the end of the 18th century, the specific experience of granting voting rights to unmarried women who owned property in New Jersey, together with how they exercised this right during the short time they enjoyed it, has become more visible in historiography. The narratives usually feature three main periods: the first New Jersey Constitution in 1776, the legislation and statutes in the 1790s, and the backlash against New Jersey female voters in 1807. This article first seeks to introduce the key aspects of the history of women’s voting rights in the British colonies of North America, the United States, and some northern and western European countries at the end of the 18th century. It then provides the major elements in the history of New Jersey’s female voters around the turn of the 19th century. The final part highlights how suffragists in the 19th century referred to New Jersey’s historical precedent to denounce the lack of suffrage for all female U.S. citizens. Part 1 – Women’s privileges and rights in the 18th century Voting rights were granted—temporarily—to unmarried and property- owning women in New Jersey during the Enlightenment and the American Revolution.1 The theory of natural rights and the idea of a social contract, which had been gaining popularity since the 17th century, were fully debated and put into practice in certain cases. Broadly speaking, one key tenet of the Enlightenment was that the equality of men in the state of nature requires them to establish a social contract for all. -

Select Bibliography of Virginia Women's History

GENERAL AND REFERENCE James, Edward T., Janet Wilson James, and Paul S. Boyer, eds. Notable American Women, 1607–1950: A Biographical Dictionary. 3 vols. 1971. Kneebone, John T., et al., eds. Dictionary of Virginia Biography. 1998– . Lebsock, Suzanne. “A Share of Honour”: Virginia Women, 1600–1945. 1984; 2d ed., Virginia Women, 1600–1945: "A Share of Honour." 1987. Scott, Anne Firor. Natural Allies: Women's Associations in American History. 1991. Sicherman, Barbara, and Carol Hurd Green, eds. Notable American Women: The Modern Period. 1980. Strasser, Susan. Never Done: A History of American Housework. 1982. Tarter, Brent. "When 'Kind and Thrifty Husbands' Are Not Enough: Some Thoughts on the Legal Status of Women in Virginia." Magazine of Virginia Genealogy 33 (1995): 79–101. Treadway, Sandra Gioia. "New Directions in Virginia Women's History." Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 100 (1992): 5–28. Wallenstein, Peter. Tell The Court I Love My Wife: Race, Marriage, and Law: An American History. 2002. 1 NATIVE AMERICANS Axtell, James, ed. The Indian Peoples of Eastern America: A Documentary History of the Sexes. 1981. Barbour, Philip L. Pocahontas and Her World. 1970. Green, Rayna. "The Pocahontas Perplex: The Image of Indian Women in American Culture." Massachusetts Review 16 (1975): 698–714. Lurie, Nancy Oestreich. "Indian Cultural Adjustment to European Civilization." In Seventeenth-Century America: Essays in Colonial History, edited by James Morton Smith. 1959. Rountree, Helen C. The Powhatan Indians of Virginia: Their Traditional Culture. 1989. Rountree, Helen C. Pocahontas's People: The Powhatan Indians of Virginia through Four Centuries. 1990. Smits, David D. "'Abominable Mixture': Toward the Repudiation of Anglo-Indian Intermarriage in Seventeenth-Century Virginia." Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 95 (1987): 157–192. -

The Diaries of George Washington. Vol. 4. Donald Jackson, and Dorothy Twohig, Eds

The Diaries of George Washington. Vol. 4. Donald Jackson, and Dorothy Twohig, eds. The Papers of George Washington. Charlottesville The Diaries of GEORGE WASHINGTON Volume IV 1784–June 1786 ASSISTANT EDITORS Beverly H. Runge, Frederick Hall Schmidt, and Philander D. Chase George H. Reese, Consulting Editor Joan Paterson Kerr, Picture Editor THE DIARIES OF GEORGE WASHINGTON Volume IV 1784–June 1786 DONALD JACKSON AND DOROTHY TWOHIG EDITORS UNIVERSITY PRESS OF VIRGINIA CHARLOTTESVILLE This edition has been prepared by the staff of The Papers of George Washington, sponsored by The Mount Vernon Ladies' Association of the Union and the University of Virginia with the support of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the National Historical Publications and Records Commission. THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF VIRGINIA Copyright © 1978 by the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia First published 1978 Frontispiece: Samuel Vaughan's sketch of Mount Vernon, from his 1787 journal. (Collection of the descendents of Samuel Vaughan) Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data (Revised) Washington, George, Pres. U.S., 1732–1799. The diaries of George Washington. The Diaries of George Washington. Vol. 4. Donald Jackson, and Dorothy Twohig, eds. The Papers of George Washington. Charlottesville http://www.loc.gov/resource/mgw.wd04 Includes bibliographies and indexes. 1. Washington, George, Pres. U.S., 1732–1799. 2. Presidents—United States—Biography. I. Jackson, Donald Dean, 1919- II. Twohig, Dorothy. III. Title. E312.8 1976 973.4′1′0924 [B] 75-41365 ISBN 0-8139-0722-5 Printed in the United States of America Administrative Board David A. Shannon, Chairman Mrs. -

Wall of Honor Names Final

Voices from the Garden: The Virginia Women’s Monument WALL OF HONOR Em Bowles Locker Alsop Hazel K. Barger Pocahontas (Matoaka) Janie Porter Barrett Kate Waller Barrett Anne Burras Laydon M. Majella Berg Cockacoeske Frances Berkeley Martha Washington Ann Bignall Mary Draper Ingles Aline E. Black Clementina Rind Mary Blackford Elizabeth Keckly Catherine Blaikley Sally L. Tompkins Florence A. Blanchfield Maggie L. Walker Anna Bland Sarah G. Jones Cynthia Boatwright Laura S. Copenhaver Elisabeth S. Bocock Virginia E. Randolph Anna W. Bodeker Adèle Clark Carrie J. Bolden Mary Marshall Bolling Pauline F. Adams Matilda M. Booker Mollie Adams Gladys Boone Lucy Addison Dorothy Rouse Bottom Mary Aggie Geline MacDonald Bowman Ella G. Agnew Mary Richards Bowser Mary C. Alexander Rosa D. Bowser Sharifa Alkhateeb Belle Boyd Susie M. Ames Sarah Patton Boyle Eleanor Copenhaver Anderson Mildred Bradshaw V. C. Andrews Lucy Goode Brooks Orie Moon Andrews Belle S. Bryan Ann (Pamunkey chief) Mary E. Brydon Grace Arents Annabel Morris Buchanan Nancy Astor Dorothea D. Buck Addie D. Atkinson Pattie Buford Anne Bailey Evelyn T. Butts Odessa P. Bailey Mary Willing Byrd Mary Julia Baldwin Sadie Heath Cabaniss Lucy Barbour Mary Virginia Ellet Cabell Voices from the Garden: The Virginia Women’s Monument WALL OF HONOR Willie Walker Caldwell Rachel Findlay Edith Lindeman Calisch Edith Fitzgerald Christiana Campbell Ella Fitzgerald Elizabeth Pfohl Campbell Eve D. Fout Eliza J. Carrington Ethel Bailey Furman Maybelle Carter Elizabeth Furness Sara Carter Mary Jeffery Galt Virginia Cary Charlotte C. Giesen Ruth Harvey Charity Ellen Glasgow Jean Outland Chrysler Meta Glass Patsy Cline Thelma Young Gordon Matty L.