1 the Case for Body Positivity on Social Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Role of Body Fat and Body Shape on Judgment of Female Health and Attractiveness: an Evolutionary Perspective

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Psychological Topics 15 (2006), 2, 331-350 Original Scientific Article – UDC 159.9.015.7.072 572.51-055.2 Role of Body Fat and Body Shape on Judgment of Female Health and Attractiveness: An Evolutionary Perspective Devendra Singh University of Texas at Austin Department of Psychology Dorian Singh Oxford University Department of Social Policy and Social Work Abstract The main aim of this paper is to present an evolutionary perspective for why women’s attractiveness is assigned a great importance in practically all human societies. We present the data that the woman’s body shape, or hourglass figure as defined by the size of waist-to-hip-ratio (WHR), reliably conveys information about a woman’s age, fertility, and health and that systematic variation in women’s WHR invokes systematic changes in attractiveness judgment by participants both in Western and non-Western societies. We also present evidence that attractiveness judgments based on the size of WHR are not artifact of body weight reduction. Then we present cross-cultural and historical data which attest to the universal appeal of WHR. We conclude that the current trend of describing attractiveness solely on the basis of body weight presents an incomplete, and perhaps inaccurate, picture of women’s attractiveness. “... the buttocks are full but her waist is narrow ... the one for who[m] the sun shines ...” (From the tomb of Nefertari, the favorite wife of Ramses II, second millennium B.C.E.) “... By her magic powers she assumed the form of a beautiful woman .. -

How Can Storytelling Facilitate Body Positivity in Young Women

Lesley University DigitalCommons@Lesley Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences Expressive Therapies Capstone Theses (GSASS) Spring 5-18-2019 How can Storytelling Facilitate Body Positivity in Young Women Struggling with their Bodies?: Literature Review Natalie Slaughter Lesley University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/expressive_theses Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Slaughter, Natalie, "How can Storytelling Facilitate Body Positivity in Young Women Struggling with their Bodies?: Literature Review" (2019). Expressive Therapies Capstone Theses. 119. https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/expressive_theses/119 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School of Arts and Social Sciences (GSASS) at DigitalCommons@Lesley. It has been accepted for inclusion in Expressive Therapies Capstone Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Lesley. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RUNNING HEAD: STORYTELLING AND BODY POSITIVITY How can Storytelling Facilitate Body Positivity in Young Women Struggling with their Bodies?: Literature Review Capstone Thesis Lesley University April 10 2019 Natalie Slaughter Drama Therapy Christine Mayor 1 RUNNING HEAD: STORYTELLING AND BODY POSITIVITY Abstract In a society that promotes a “thin ideal”, it can be difficult for women to accept their bodies. Body positivity is a combination of positive body image, self-confidence, and body acceptance regardless of size, shape, or weight of the body (Caldeira & Ridder, 2017; Dalley & Vidal, 2013; Halliwell, 2015; Wood-Barcalow, Tylka, & Augustus-Horvath, 2010). This literature review presents an overview of the research conducted on body positivity and storytelling, finding that there are limited interventions currently being used to promote body positivity. -

The Effect of Priming a Thin Ideal on the Subsequent Perception of Conceptually Related Body Image Words

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Psychology Faculty Publications Psychology Department 1-1-2011 The Effect of Priming a Thin Ideal on the Subsequent Perception of Conceptually Related Body Image Words Conor T. McLennan Cleveland State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/clpsych_facpub Part of the Cognition and Perception Commons, and the Health Psychology Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Publisher's Statement (c) 2011 Elsevier Recommended Citation Teresa A. Markis, Conor T. McLennan, The effect of priming a thin ideal on the subsequent perception of conceptually related body image words, Body Image, Volume 8, Issue 4, September 2011, Pages 423-426, ISSN 1740-1445, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.05.001. (http://www.sciencedirect.com/ science/article/pii/S174014451100057X) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Psychology Department at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Psychology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Brief research report The effect of priming a thin ideal on the subsequent perception of conceptually related body image words ∗ Teresa A. Markis , Conor T. McLennan Department of Psychology, Cleveland State University, Cleveland, OH, United States Introduction ideal media could become a vicious cycle if after the development of an initial dissatisfaction, patients with an eating disorder paid Contemporary media promote a thin ideal standard that leads extra attention to exactly the types of stimuli that led to the dissat- many females to feel badly about their weight and shape. -

Disordered Eating As a Consequence of Thin-Ideal Television: an Investigation of Internalization and Self-Monitoring As Potential Vulnerability Factors Arielle S

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2011 Disordered Eating as a Consequence of Thin-Ideal Television: An Investigation of Internalization and Self-Monitoring as Potential Vulnerability Factors Arielle S. Gartenburg Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Psychiatry and Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Gartenburg, Arielle S., "Disordered Eating as a Consequence of Thin-Ideal Television: An Investigation of Internalization and Self- Monitoring as Potential Vulnerability Factors" (2011). Honors Theses. 980. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/980 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running Title: Disordered Eating & Moderating Factors Disordered Eating as a Consequence of Thin-Ideal Television: An Investigation of Internalization and Self-Monitoring as Potential Vulnerability Factors By Arielle S. Gartenberg ********* Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Psychology UNION COLLEGE, June, 2011 Disordered Eating & Vulnerability Factors ii ABSTRACT GARTENBERG, ARIELLE Disordered eating as a consequence of the thin- ideal: An investigation of internalization and self-monitoring as potential moderating factors. Department of Psychology, June 2011. ADVISOR: Linda Stanhope, Ph.D. This study investigated the association between television exposure and disordered eating, with an emphasis on the potential moderating effects of self- monitoring and thin-ideal internalization. Minimal research has explored the relationship between self-monitoring and eating disorders, and no previous studies have examined the correlation between self-monitoring and the thin-ideal. -

Understanding 7 Understanding Body Composition

PowerPoint ® Lecture Outlines 7 Understanding Body Composition Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Objectives • Define body composition . • Explain why the assessment of body size, shape, and composition is useful. • Explain how to perform assessments of body size, shape, and composition. • Evaluate your personal body weight, size, shape, and composition. • Set goals for a healthy body fat percentage. • Plan for regular monitoring of your body weight, size, shape, and composition. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Body Composition Concepts • Body Composition The relative amounts of lean tissue and fat tissue in your body. • Lean Body Mass Your body’s total amount of lean/fat-free tissue (muscles, bones, skin, organs, body fluids). • Fat Mass Body mass made up of fat tissue. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Body Composition Concepts • Percent Body Fat The percentage of your total weight that is fat tissue (weight of fat divided by total body weight). • Essential Fat Fat necessary for normal body functioning (including in the brain, muscles, nerves, lungs, heart, and digestive and reproductive systems). • Storage Fat Nonessential fat stored in tissue near the body’s surface. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Why Body Size, Shape, and Composition Matter Knowing body composition can help assess health risks. • More people are now overweight or obese. • Estimates of body composition provide useful information for determining disease risks. Evaluating body size and shape can motivate healthy behavior change. • Changes in body size and shape can be more useful measures of progress than body weight. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. Body Composition for Men and Women Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. -

Relationship Between Body Image and Body Weight Control in Overweight ≥55-Year-Old Adults: a Systematic Review

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Review Relationship between Body Image and Body Weight Control in Overweight ≥55-Year-Old Adults: A Systematic Review Cristina Bouzas , Maria del Mar Bibiloni and Josep A. Tur * Research Group on Community Nutrition and Oxidative Stress, University of the Balearic Islands & CIBEROBN (Physiopathology of Obesity and Nutrition CB12/03/30038), E-07122 Palma de Mallorca, Spain; [email protected] (C.B.); [email protected] (M.d.M.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-971-1731; Fax: +34-971-173184 Received: 21 March 2019; Accepted: 7 May 2019; Published: 9 May 2019 Abstract: Objective: To assess the scientific evidence on the relationship between body image and body weight control in overweight 55-year-old adults. Methods: The literature search was conducted ≥ on MEDLINE database via PubMed, using terms related to body image, weight control and body composition. Inclusion criteria were scientific papers, written in English or Spanish, made on older adults. Exclusion criteria were eating and psychological disorders, low sample size, cancer, severe diseases, physiological disorders other than metabolic syndrome, and bariatric surgery. Results: Fifty-seven studies were included. Only thirteen were conducted exclusively among 55-year-old ≥ adults or performed analysis adjusted by age. Overweight perception was related to spontaneous weight management, which usually concerned dieting and exercising. More men than women showed over-perception of body image. Ethnics showed different satisfaction level with body weight. As age increases, conformism with body shape, as well as expectations concerning body weight decrease. Misperception and dissatisfaction with body weight are risk factors for participating in an unhealthy lifestyle and make it harder to follow a healthier lifestyle. -

The Moderating Role of Thin Ideal Internalization on Advertising Effectiveness

Atlantic Marketing Journal Volume 4 Number 1 Volume 4 Number 1: Winter 2015 Article 1 May 2015 Does Thin Always Sell? The Moderating Role of Thin Ideal Internalization on Advertising Effectiveness James A. Roberts Baylor University, [email protected] Chloe' A. Roberts University of Alabama, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/amj Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, Applied Behavior Analysis Commons, Experimental Analysis of Behavior Commons, and the Marketing Commons Recommended Citation Roberts, James A. and Roberts, Chloe' A. (2015) "Does Thin Always Sell? The Moderating Role of Thin Ideal Internalization on Advertising Effectiveness," Atlantic Marketing Journal: Vol. 4 : No. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.kennesaw.edu/amj/vol4/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Atlantic Marketing Journal by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Kennesaw State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Does Thin Always Sell? The Moderating Role of Thin Ideal Internalization on Advertising Effectiveness James A. Roberts, Baylor University [email protected] Chloe’ Roberts, University of Alabama [email protected] Abstract - Much of the current focus on the use of ultra-thin models in fashion magazines can be attributed to Madison Avenue which still operates under a “Thin Sells” ethos. Research to date, however, has provided equivocal evidence of the efficacy of thin models in advertising (Yu, 2014). The present study’s two related objectives include: (1) determining whether model size has an impact on advertising effectiveness, and (2) if internalization of the thin ideal moderates this relationship. -

Refining the Abdominoplasty for Better Patient Outcomes

Refining the Abdominoplasty for Better Patient Outcomes Karol A Gutowski, MD, FACS Private Practice University of Illinois & University of Chicago Refinements • 360o assessment & treatment • Expanded BMI inclusion • Lipo-abdominoplasty • Low scar • Long scar • Monsplasty • No “dog ears” • No drains • Repurpose the fat • Rapid recovery protocols (ERAS) What I Do and Don’t Do • “Standard” Abdominoplasty is (almost) dead – Does not treat the entire trunk – Fat not properly addressed – Problems with lateral trunk contouring – Do it 1% of cases • Solution: 360o Lipo-Abdominoplasty – Addresses entire trunk and flanks – No Drains & Rapid Recovery Techniques Patient Happy, I’m Not The Problem: Too Many Dog Ears! Thanks RealSelf! Take the Dog (Ear) Out! Patients Are Telling Us What To Do Not enough fat removed Not enough skin removed Patient Concerns • “Ideal candidate” by BMI • Pain • Downtime • Scar – Too high – Too visible – Too long • Unnatural result – Dog ears – Mons aesthetics Solutions • “Ideal candidate” by BMI Extend BMI range • Pain ERAS protocols + NDTT • Downtime ERAS protocols + NDTT • Scar Scar planning – Too high Incision markings – Too visible Scar care – Too long Explain the need • Unnatural result Technique modifications – Dog ears Lipo-abdominoplasty – Mons aesthetics Mons lift Frequent Cause for Reoperation • Lateral trunk fullness – Skin (dog ear), fat, or both • Not addressed with anterior flank liposuction alone – need posterior approach • Need a 360o approach with extended skin excision (Extended Abdominoplasty) • Patient -

Exposure to Thin-Ideal Media Affect Most, but Not All, Women: Results

Body Image 23 (2017) 188–205 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Body Image journa l homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/bodyimage Exposure to thin-ideal media affect most, but not all, women: Results from the Perceived Effects of Media Exposure Scale and open-ended responses a,∗ b a c David A. Frederick , Elizabeth A. Daniels , Morgan E. Bates , Tracy L. Tylka a Crean College of Health and Behavioral Sciences, Chapman University, Orange, USA b Department of Psychology, University of Colorado at Colorado Springs, USA c Department of Psychology, Ohio State University, Columbus, USA a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Findings conflict as to whether thin-ideal media affect women’s body satisfaction. Meta-analyses of Received 22 November 2016 experimental studies reveal small or null effects, but many women endorse appearance-related media Received in revised form 15 October 2017 pressure in surveys. Using a novel approach, two samples of women (Ns = 656, 770) were exposed to bikini Accepted 16 October 2017 models, fashion models, or control conditions and reported the effects of the images their body image. Many women reported the fashion/bikini models made them feel worse about their stomachs (57%, 64%), Keywords: weight (50%, 56%), waist (50%, 56%), overall appearance (50%, 56%), muscle tone (46%, 52%), legs (45%, Thin-ideal media 48%), thighs (40%, 49%), buttocks (40%, 43%), and hips (40%, 46%). In contrast, few women (1-6%) reported Body image negative effects of control images. In open-ended responses, approximately one-third of women explic- Sociocultural theory itly described negative media effects on their body image. -

Body Positivity “I Could Have Never Imagined How Much It Would Cost Me to Attempt to Reach the Standard of Today’S Beauty

Body Positivity “I could have never imagined how much it would cost me to attempt to reach the standard of today’s beauty. —Sadie Roberston, “I Woke Up Like This” Beyoncé Was Right: When It Comes to Beauty, “It’s the Soul That Needs the Surgery” Katrina (not her real name) struggled through middle school and high school. It was a difficult time for her, not simply because she was socially awkward, but also because of how she looked. She rarely felt pretty: She struggled on and off with acne, had braces for a while, and had no idea what to do with her crazy hair. To add insult to injury, she didn’t know how to dress stylishly and would often feel embarrassed about her clothes. Our society puts a heavy burden on people, women in particular, to measure up to certain standards of physical beauty. The body positivity movement has arisen in response to these unattainable ideals. It attempts to redefine beauty and human worth and has made its way from social media platforms like Instagram and Twitter into our mainstream marketing. But is it the answer that all teenagers who struggle to accept themselves desperately long for? Despite the necessity of this movement, or at least something like it, body positivity is complicated and nuanced—and very worth talking about with your teens. How do teens feel about their bodies? In her book, Unashamed: Healing Our Brokenness and Finding Freedom from Shame, Heather Davis Nelson writes, “Shame commonly masquerades as embarrassment, or the nagging sense of ‘not quite good enough.’” This is how Katrina felt, and it’s a feeling that many teens can relate to, especially when it comes to their bodies. -

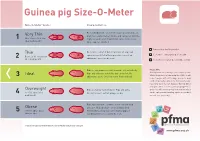

Guinea Pig Size-O-Meter Will 3 Abdominal Curve

Guinea pig Size-O- Meter Size-O-Meter Score: Characteristics: Each individual rib can be felt easily, hips and spine are Very Thin prominent and extremely visible and can be felt with the 1 More than 20% below slightest touch. Under abdominal curve can be seen. ideal body weight Spine appears hunched. Your pet is a healthy weight Thin Each rib is easily felt but not prominent. Hips and spine are easily felt with no pressure. Less of an Seek advice about your pet’s weight Between 10-20% below 2 abdominal curve can be seen. ideal body weight Seek advice as your pet could be at risk Ribs are not prominent and cannot be felt individually. Please note Hips and spine are not visible but can be felt. No Getting hands on is the key to this simple system. Ideal Whilst the pictures in Guinea pig Size-O-Meter will 3 abdominal curve. Chest narrower then hind end. help, it may be difficult to judge your pet’s body condition purely by sight alone. Some guinea pigs have long coats that can disguise ribs, hip bones and spine, while a short coat may highlight these Overweight Ribs are harder to distinguish. Hips and spine areas. You will need to gently feel your pet which 4 10 -15% above ideal difficult to feel. Feet not always visible. can be a pleasurable bonding experience for both body weight you and your guinea pig. Ribs, hips and spine cannot be felt or can with mild Obese pressure. No body shape can be distinguished. -

Running Head: BODY MASS INDEX and MEDIA IMAGES 1

Running head: BODY MASS INDEX AND MEDIA IMAGES 1 Body Dissatisfaction: The Effects of Body Mass Index on Reactions to Media Images A Senior Honors Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for graduation with research distinction in Psychology in the undergraduate colleges of The Ohio State University By Lyndsee Cooper The Ohio State University at Mansfield May 2011 Project Advisor: Dr. Philip Mazzocco, Department of Psychology Running head: BODY MASS INDEX AND MEDIA IMAGES 2 Abstract Media images have been shown to affect the way women perceive their selves. The effect body mass index (BMI) has on body dissatisfaction when viewing media images has not been determined. This study used 121 female college students. Participants reported their height and weight before being assigned to one of three image-exposure conditions: moderately-thin female models, ultra-thin female models, or neutral media images. After viewing the images, they then reported their body dissatisfaction. Results indicated increased body dissatisfaction only when participants with moderate BMI viewed thin or ultra-thin models. These findings have implications for advertisement, media literacy programs, and eating disorder preventions. Running head: BODY MASS INDEX AND MEDIA IMAGES 3 Body Dissatisfaction: The Effects of Body Mass Index on Reactions to Media Images Social comparisons are an important part of daily life, and in the age of media, this may be particularly true for women. Myers and Crowther (2009) found that women compare themselves to thin media images just as frequently as they compare themselves to peers who are more relevant. Body satisfaction is an important aspect of the way people live their lives.