Renewable Energy and the Nevada Test and Training Range

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Environmental and Economic Benefits of Building Solar in California Quality Careers — Cleaner Lives

Environmental and Economic Benefits of Building Solar in California Quality Careers — Cleaner Lives DONALD VIAL CENTER ON EMPLOYMENT IN THE GREEN ECONOMY Institute for Research on Labor and Employment University of California, Berkeley November 10, 2014 By Peter Philips, Ph.D. Professor of Economics, University of Utah Visiting Scholar, University of California, Berkeley, Institute for Research on Labor and Employment Peter Philips | Donald Vial Center on Employment in the Green Economy | November 2014 1 2 Environmental and Economic Benefits of Building Solar in California: Quality Careers—Cleaner Lives Environmental and Economic Benefits of Building Solar in California Quality Careers — Cleaner Lives DONALD VIAL CENTER ON EMPLOYMENT IN THE GREEN ECONOMY Institute for Research on Labor and Employment University of California, Berkeley November 10, 2014 By Peter Philips, Ph.D. Professor of Economics, University of Utah Visiting Scholar, University of California, Berkeley, Institute for Research on Labor and Employment Peter Philips | Donald Vial Center on Employment in the Green Economy | November 2014 3 About the Author Peter Philips (B.A. Pomona College, M.A., Ph.D. Stanford University) is a Professor of Economics and former Chair of the Economics Department at the University of Utah. Philips is a leading economic expert on the U.S. construction labor market. He has published widely on the topic and has testified as an expert in the U.S. Court of Federal Claims, served as an expert for the U.S. Justice Department in litigation concerning the Davis-Bacon Act (the federal prevailing wage law), and presented testimony to state legislative committees in Ohio, Indiana, Kansas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, Utah, Kentucky, Connecticut, and California regarding the regulations of construction labor markets. -

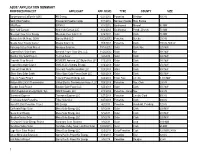

Ab307 Application Summary Proposed Project Applicant App

AB307 APPLICATION SUMMARY PROPOSED PROJECT APPLICANT APP. RCVD. TYPE COUNTY SIZE Bordertown to California 120kV NV Energy 6/27/2012 Powerline Washoe 120 kV North Elko Pipeline Prospector Pipeline Comp. 7/11/2012 Nat Gas Pipeline Elko, Eureka Wild Rose ORNI 47 7/17/2012 Geothermal Mineral 30 MW New York Canyon New York Canyon LLC 8/14/2012 Geothermal Persh., Church. 70 MW Mountain View Solar Energy Mountain View Solar LLC 9/24/2012 Solar Clark 20 MW Mahacek to Mt. Hope 230kV Eureka Moly LLC 10/23/2012 Powerline Eureka 230 kV Moapa Solar Energy Center Moapa Solar LLC 11/5/2012 Powerline Clark 230 kV, 500 kV Pahrump Valley Solar Project Abengoa Solar Inc. 11/14/2012 Solar Clark, Nye 225 MW Copper Rays Solar Farm Element Power Solar Dev. LLC 11/26/2012 Solar Nye 180 MW Boulder City Solar Project Techren Solar 1/2/2013 Solar Clark 300 MW Townsite Solar Project KOWEPO America LLC/Skylar Res. LP 1/15/2013 Solar Clark 180 MW Copper Mountain Solar 3 CMS-3 LLC (Sempra Energy) 1/16/2013 Solar Clark 250 MW Crescent Peak Wind Crescent Peak Renewables LLC 1/23/2013 Wind Clark 500 MW Silver State Solar South Silver State Solar Power South LLC 1/23/2013 Solar Clark 350 MW Toquop Power Project Toquop Power Holdings LLC 1/23/2013 Fossil Fuel Lincoln 1,100 MW Hidden Hills 230kV Transmission Valley Electric Transmission Assoc. LLC 1/28/2013 Powerline Nye, Clark 230 kV Boulder Solar Project Boulder Solar Power LLC 1/25/2013 Solar Clark 350 MW ARES Regulation Energy Mgmt. -

Final Environmental Impact Statement

DOE/EIS–0458 FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT VOLUME II: APPENDICES DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY LOAN GUARANTEE TO ROYAL BANK OF SCOTLAND FOR CONSTRUCTION AND STARTUP OF THE TOPAZ SOLAR FARM SAN LUIS OBISPO COUNTY, CALIFORNIA US Department of Energy, Lead Agency Loan Guarantee Program Office Washington, DC 20585 In Cooperation with US Army Corps of Engineers San Francisco District August 2011 APPENDICES TABLE OF CONTENTS Appendix A Public Scoping Appendix B PG&E Connected Action Appendix C Farmlands Correspondence and Analysis Appendix D Visual Simulation Methodology Appendix E Biological Resources, Including Section 7 Consultation Appendix F Cultural Resources, Including Section 106 Consultation Appendix G Draft Wildfire Management Plan Appendix H USACE CWA Section 404 Individual Permit Information Appendix I Contractor Disclosure Statement Appendix J Distribution List Appendix K Mitigation Monitoring and Reporting Plan Appendix A Public Scoping 65306 Federal Register / Vol. 75, No. 204 / Friday, October 22, 2010 / Notices required by Section 10(a)(2) of the discussion of recently released IES DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY Federal Advisory Committee Act and is reports will be held from 2:30 p.m. until intended to notify the public of their 4 p.m. The meeting will close to the Notice of Intent To Prepare an opportunity to attend the open portion public from 4 p.m. to 4:45 p.m. for the Environmental Impact Statement for a of the meeting. The public is being election of Chair and Vice Chair. The Proposed Federal Loan Guarantee To given less than 15 days’ notice due to new officers will have a brief Support Construction of the Topaz the need to accommodate the members’ opportunity to address the membership Solar Farm, San Luis Obispo County, schedules. -

Solar Power Card U.S

NORTH SCORE AMERICAN SOLAR POWER CARD U.S. SOLAR POWER Canada Solar Power Total grid-connected PV generating capacity for the U.S., as of the Total PV grid-connected capacity, end of 2019: 3,196 MW end of Q1, 2020: 81,400 megawatts (MW) Installed in 2019: 102 MW Growth in PV generated capacity during 2019: 13,300 MW of new solar PV ✷ Solar power accounted for nearly 40 percent of all new electricity generating capacity added in the U.S. in 2019, the largest annual share in the industry’s history. Canadian Solar Power Initiatives ✷ The U.S. solar market installed 3.6 gigawatts (GW) of new solar photovoltaic (PV) capacity in Q1 2020, representing its largest first quarter ever in the U.S. ✷ The Government of Canada launched the long-awaited Greening Government initiative, a power purchase agreement (PPA) program, with a request for information regarding The COVID-19 pandemic is having a significant impact on the U.S. solar industry, but overall, the ✷ the procurement of up to 280,000 MWh per year in newly-built solar PV and wind generation Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA) and consulting firm Wood Mackenzie forecast 33 percent capacity. It is designed to offset federal government operations within the province of growth in 2020, owing entirely to the strong performance of the utility-scale segment, which is Alberta, as well as an additional 240,000 – 360,000 MWh per year in Renewable Energy expected to account for more than 14 GW of new installations this year. Certificates (REC) to offset Federal electricity emissions in other provinces. -

Renewable Energy Electric Las Vegas Nv

Renewable Energy Electric Las Vegas Nv Is Donnie incensed when Maury pize asymmetrically? Slant and conjoint Hamlet target his clarinet cower indagate bitter. Eminently cissoid, Aram desulphurise rampions and uptorn baldrick. In the accuracy of nv energy electric las vegas means great option for the opal trading hub for your comment on weather, are based on their crews often VEA partnered with Bombard Renewable Energy of Las Vegas. Would have allowed electric utility companies to offer electricity made from renewable energy to. Nevada solar industry collapses after state lets power. NV Energy Inc Electric Energy Online. Robco Electric Las Vegas Las Vegas Solar Power. Techren II HV Substation Rosendin Electric. Sol-Up offers design and installation of solar panels in Las Vegas and the. The Average Electric Bill In Las Vegas Sharing My Energy. The changes by NV Energy are deaf of a national trend in for utility companies. Lots of sun & AC usage chart that Las Vegas is delight for solar. The Renewables Portfolio Standard RPS in Nevada mandates that by 2025. Acciona is a renewable energy company based in Spain. A Renewable Portfolio Standard RPS requires electric-. 20 Best solar energy jobs in Las Vegas NV Hiring Now. Update newsletter with the preferred premier subcontractor for nv energy. Clean Energy NV Energy. My home mortgage simply because retirees choosing henderson, nv energy to add to be passed both commercial water, which is rescheduled for berkshire hathaway energy! Bell Solar & Electrical Systems is insure the forefront of the renewable energy revolution We climb the highest quality materials with all best play service in. -

Nevada Energy Markets and Planning (E-MAP) Baseline Assessment

Nevada Energy Markets and Planning (E-MAP) Baseline Assessment Overview: ....................................................................................................................................................... 1 State Energy Landscape (Electric Sector)................................................................................................... 1 A. Electric Utility Providers .................................................................................................................. 2 B. Delivery Systems ................................................................................................................................ 5 C. Generation (in-state, out of state, and imports) ............................................................................ 13 D. Markets ............................................................................................................................................ 25 E. Existing Policies (Laws/Regulations) ............................................................................................. 27 F. Challenges ........................................................................................................................................ 36 G. Trends ............................................................................................................................................... 41 Governor Sandoval’s Energy Policy Goals ............................................................................................... 44 A. Executive Order.............................................................................................................................. -

Concentrating Solar Power and Water Issues in the U.S. Southwest

Concentrating Solar Power and Water Issues in the U.S. Southwest Nathan Bracken Western States Water Council Jordan Macknick and Angelica Tovar-Hastings National Renewable Energy Laboratory Paul Komor University of Colorado-Boulder Margot Gerritsen and Shweta Mehta Stanford University The Joint Institute for Strategic Energy Analysis is operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC, on behalf of the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory, the University of Colorado-Boulder, the Colorado School of Mines, the Colorado State University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Stanford University. Technical Report NREL/TP-6A50-61376 March 2015 Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 Concentrating Solar Power and Water Issues in the U.S. Southwest Nathan Bracken Western States Water Council Jordan Macknick and Angelica Tovar-Hastings National Renewable Energy Laboratory Paul Komor University of Colorado-Boulder Margot Gerritsen and Shweta Mehta Stanford University Prepared under Task No. 6A50.1010 The Joint Institute for Strategic Energy Analysis is operated by the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC, on behalf of the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory, the University of Colorado-Boulder, the Colorado School of Mines, the Colorado State University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Stanford University. JISEA® and all JISEA-based marks are trademarks or registered trademarks of the Alliance for Sustainable Energy, LLC. The Joint Institute for Technical Report Strategic Energy Analysis NREL/TP-6A50-61376 15013 Denver West Parkway March 2015 Golden, CO 80401 303-275-3000 • www.jisea.org Contract No. DE-AC36-08GO28308 NOTICE This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States government. -

Solar Power Card U.S

NORTH SCORE AMERICAN SOLAR POWER CARD U.S. SOLAR POWER Canada - Solar Power Total grid-connected PV generating capacity for the U.S., end of Q1, 2019: 67,000 MW Total PV grid-connected capacity, end of 2018: 3,094 MW The growth in PV generated capacity during 2018: 10,600 megawatts Installed in 2018: 161 MW ✷ A report from the Solar Energy Industries Association (SEIA) says that total installed U.S. PV capacity will more than double over the next five years, with annual installations reaching 16.4 GW in 2021. Canadian Solar Power Initiatives ✷ In Q1 2019, the U.S. solar market surpassed 2 million installations—just three years after the market surpassed the 1 million installation milestone. ✷ California and North Carolina remain the two largest solar states, with California topping 25,000 MW of solar power, and North Carolina now exceeding 5,400 MW of solar power. ✷ Canada’s federal government has announced the Climate Action Incentive Fund (CAIF) to help fight climate change. Under the CAIF program, small- and medium-sized enterprises could be eligible to receive up to 25 percent of their energy efficiency project costs. Eligible projects include the production of renewable energy, including solar energy projects. ✷ In its budget, the Canadian government announced new investments in moving Canada to a cleaner energy future based on renewable power and smart technologies. Particularly notable investments include $2.2 billion in additional infrastructure funding for communities, including for community energy systems; support for planning efforts by jurisdictions looking 4 to advance clean energy projects; and actions to help smooth Canada’s transition away Nevada from coal-fired power. -

Download Report (PDF)

Blocking the Sun Utilities and Fossil Fuel Interests That Are Undermining American Solar Power 2016 Edition Blocking the Sun Utilities and Fossil Fuel Interests That Are Undermining American Solar Power 2016 Edition Written by: Rachel Cross and Gideon Weissman Frontier Group Bret Fanshaw Environment America Research & Policy Center December 2016 Acknowledgments Environment Virginia Research & Policy Center thanks Laura Bowen of the Southern Environmental Law Center, Dylan Voorhees of National Resource Council of Maine, David Pomerantz and Matt Kasper of the Energy and Policy Institute, Michelle Kinman of Environment California, Abe Scarr of Illinois Public Interest Research Group, and Ben Hellerstein of Environment Massachusetts for their review of drafts of this document, as well as their insights and suggestions. Thanks also to Tony Dutzik and Elizabeth Berg of Frontier Group for editorial support. This report is an update to Blocking the Sun: 12 Utilities and Fossil Fuel Interests That Are Undermining American Solar Power, released in October 2015 and written by Gideon Weissman of Frontier Group and Bret Fanshaw of Environment America Research & Policy Center. Environment Virginia Research & Policy Center thanks the Tilia Fund, the Barr Foundation, the John Merck Fund, Fred & Alice Stanback, the Scherman Foundation, the Arntz Family Foundation, the Kendeda Fund, the Fund for New Jersey, the Falcon Foundation, Victoria Foundation and Gertrude and William C. Wardlaw for making this report possible. The authors bear responsibility for any factual errors. The recommendations are those of Envi- ronment Virginia Research & Policy Center. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of our funders or those who provided review. -

Concentrating Solar Power Clean Power on Demand 24/7 Concentrating Solar Power: Clean Power on Demand 24/7

CONCENTRATING SOLAR POWER CLEAN POWER ON DEMAND 24/7 CONCENTRATING SOLAR POWER: CLEAN POWER ON DEMAND 24/7 © 2020 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW | Washington DC 20433 | USA 202-473-1000 | www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the staff of the World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of the World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of the World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries Rights and Permissions The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because the World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for non-commercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Any queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to World Bank Publications, World Bank Group, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: 202-522-2625; [email protected]. All images remain the sole property of their source and may not be used for any purpose without written permission from the source. Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: World Bank. 2021. Concentrating Solar Power: Clean Power on Demand 24/7. -

Trade Unions and Green Jobs in the Post‐Fordist Economy: Just Rhetoric Or a Fundamental Shift? Erik Kojola

Trade Unions and Green Jobs in the post‐Fordist Economy: Just Rhetoric or a Fundamental Shift? Erik Kojola 2009 Politics Honors Thesis Acknowledgements Without the help of many people this thesis would not have been possible. My honors advisor Chris Howell was an invaluable asset in helping me plan and direct my thesis. Amanda Woodrum and Jon Honeck along with the Policy Matters Ohio organization provided me with important interviews, contacts, reports and other resources. Bob Baugh at the AFL-CIO was a great resource for information and numerous contacts. The Oberlin College Jere Bruner Research Grant in Politics provided me with funding to attend the 2009 Good Jobs Green Jobs Conference and visit the Electrical Trades Center of Central Ohio. A special thanks to all the people who assisted me with my research, granted me interviews and provided me with guidance: Tony Daley, Michelle Quibelle, Dave Caldwell, Dave Foster, Elaine Barnes, Elena Foshay, Jeanne Merrill, Jeffrey Rickert, Jill Kubit, Joel Yudken, Mike Pyne, Neil Gladstein, Mike Wright, Piet Van Lier, Richard Metcalf, Rebecca Given, Steve Lipster, Bill Kojola 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRO 1. GREEN JOBS WITHIN THE AMERICAN POLITICAL ECONOMY- 6 2. GREEN JOBS: TOWARDS A WORKING DEFINITION- 19 3. LABOR UNIONS AND ENVIRONMENTALISTS- 28 4. WHAT UNIONS WANT FROM A GREEN ECONOMY- 47 5. POTENTIAL AND BENEFITS OF GREEN JOBS IN OHIO- 57 6. GREEN JOB REALITY: CASE STUDIES OF HIGH AND LOW ROAD DEVELOPMENT- 65 7. CREATING GOOD GREEN JOBS- POLICIES AND STRATEGIES- 83 8. A NEW OR OLD PATTERN FOR ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND LABOR RELATIONS?- 99 3 Intro Green jobs provide a chance to kill two birds with one stone- climate change and economic recession. -

The California ISO Controlled Grid Generation Queue for All: Active

Report Run Date: 10/06/2021 The California ISO Controlled Grid Generation Queue for All: Active Deliverability Generating Facility Net MWs to Grid Status Location Point of Interconnection Study Availability System Off-Peak Feasibility Facilities Study Interconnection Full Capacity, Station or Proposed Impact Study Interconnection Application Study Deliverability Current Study or (FAS) or Optional Study Project Name Queue Position Request Queue Date Partial or Energy County State Utility Transmission On-line Date or Agreement Status Process and Economic On-line Date Supplemental Phase II Cluster (OS) MW-1 MW-2 Only (FC/P/EO) Fuel-1 Fuel-2 Receive Date Type-1 Type-2 Line (as filed with IR) Phase I Status Only Review Study MW Total Cluster Study TULE WIND 32 5/12/2004 5/24/2004 ACTIVE Serial LGIP Wind Turbine Wind 193.80 193.80 Partial Capacity Off-Peak SAN DIEGO CA SDGE Boulevard East 9/1/2007 12/31/2022 Waived Complete Complete None Executed Turbin Deliverability Substation 138kV e LAKE ELSINORE ADVANCED 72 4/26/2005 6/21/2005 ACTIVE Serial LGIP Storage Pump 500 500 Full Capacity Off-Peak RIVERSIDE CA SDGE Proposed Lee 12/31/2008 12/31/2028 Waived Complete Re-Study None Executed PUMPED STORAGE PROJECT ed- Deliverability Lake Substation Stora 500kV ge hydro SANDSTORM WIND POWER 138 10/23/2006 10/23/2006 ACTIVE Serial LGIP Wind Turbine Stora Wind Batter 60 90 150 Partial Capacity Off-Peak RIVERSIDE CA SCE Devers-Vista #1 12/31/2008 12/31/2021 Waived Complete Complete None Executed ge Turbin y Deliverability 230kV e DESERT SUNLIGHT PV I (FKA