May, 20062006

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digital and Analog Television Interference with VHF Systems This Product Operates Between 72-87 MHZ and 170-234 Mhz

Digital and Analog Television interference with VHF systems This product operates between 72-87 MHZ and 170-234 MHz TV CH Freq MHz VHF Frequency Channel None ----- 72.300 MHz BB None ----- 72.500 MHz CC None ----- 72.700 MHz DD None ----- 72.900 MHz EE None ----- 75.500 MHz FF None ----- 75.700 MHz GG None ----- 75.900 MHz HH None ----- 81.350 MHz MB1 6 82-88 83.880 MHz MB2 6 82-88 85.275 MHz MB3 6 82-88 87.375 MHz MB4 None ----- 170.245 MHz G1 None ----- 171.905 MHz A None ----- 173.800 MHz E4 None ----- 174.100 MHz E5 7 174-180 174.500 MHz E6 7 174-180 175.000 MHz E3 7 174-180 175.550 MHz CE6 7 174-180 176.400 MHz CE7 7 174-180 176.900 MHz A14 8 180-186 183.570 MHz CE9 8 180-186 185.150 MHz B 8 180-186 185.250 MHz CE1 9 186-192 191.300 MHz H 10 192-198 195.250 MHz CE2 10 192-198 197.150 MHz N 11 198-204 202.100 MHz A1 11 198-204 203.250 MHz CE3 11 198-204 203.400 MHz F 12 204-210 206.350 MHz P 12 204-210 209.150 MHz D 13 210-216 212.100 MHz R 13 210-216 215.200 MHz E None ----- 219.200 MHz K None ----- 226.225 MHz M None ----- 231.650 MHz J2 None ----- 232.800 MHz CE5 None ----- 234.100 MHz J4 169.445, 170.245, 171.905, None ----- AT2 171.045 MHz 170.245, 171.905, 172.650, None ----- AT 170.850 MHz 182.800, 184.450, 185.150, 8 180-186 A8 183.300 MHz 182.800, 184.450, 185.150, 8 180-186 AE8 183.570 MHz 188.800, 190.450, 191.300, 9 186-192 A9 189.300 MHz 194.800, 196.450, 197.150, 10 192-198 A10 195.250 MHz Potential problems with local interference As of 10/11/04 Station Types, TV = Full Service TV, DT = Digital TV, CA = Class A, TX = Low Power TV and Translator, TB = Booster TV, TS = Auxiliary Back Up Call State CITY TV Ch. -

Agenda Regular Meeting of the Board of Commissioners Humboldt Bay Harbor, Recreation and Conservation District

AGENDA REGULAR MEETING OF THE BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS HUMBOLDT BAY HARBOR, RECREATION AND CONSERVATION DISTRICT DATE: February 11, 2021 TIME: Closed Session – 5:00 P.M. Regular Session – 6:00 P.M. PLACE: Join Zoom Meeting https://us02web.zoom.us/j/3432860852 Meeting ID: 343 286 0852 One tap mobile (669) 900-9128, 343 286 0852# US 1. Call to Order Closed Session at 5:00 P.M. 2. Public Comment Note: This portion of the Agenda allows the public to speak to the Board on the closed session items. Each speaker is limited to speak for a period of three (3) minutes regarding each item on the Closed Session Agenda. The three (3) minute time limit may not be transferred to other speakers. The three (3) minute time limit for each speaker may be extended by the President of the Board of Commissioners or the Presiding Member of the Board of Commissioners. 3. Move to Closed Session a) CONFERENCE WITH LABOR NEGOTIATORS. Agency designated representatives: Larry Oetker, Executive Director. Employee organization: Management Employees. b) CONFERENCE WITH REAL PROPERTY NEGOTIATORS. Terms of potential lease and sublease of District’s lease interest by District under lease between the District and Mario’s Marina LLC dated April 1, 2016 for the real property commonly known as Mario’s Marina in Shelter Cove (APN: 108-171-023-000), Humboldt County, California pursuant to California Government Code § 54956.8. District negotiators: Larry Oetker, Executive Director and Ryan Plotz, District Counsel. Negotiating party: Mario’s Marina and Shelter Cove Fisherman’s Preservation, Inc. Under negotiation: price and payment terms. -

Curriculum Vitae

Curriculum Vitae Daniel E. Macallair, MPA Co-Founder and Executive Director Practitioner-in-Residence Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice (CJCJ) Department of Criminal Justice Studies 40 Boardman Place San Francisco State University San Francisco, CA 94103 1600 Holloway Ave 415-621-5661 San Francisco CA 94132 415-405-4129 Selected Program Development and Management Experience Juvenile Community Reentry Partnership (2010 – present). The project is a national demonstration project funded by the United State Department of Justice to pilot model reentry services for youth offenders from San Francisco returning to the community from residential or institutional placement. The project is a partnership with the San Francisco Juvenile Probation Department and Superior Court. Community Options for Youth (2007-present). The project is a first of a kind wraparound program targeting the highest risk youths in the San Francisco juvenile justice system. It combines mental health and foster care funding to reduce the number of youth in out-of-home placement and institutional care. Sheriff’s Nova Reentry Project. (October 2006 – present). Pilot reentry project that provides case management services to inmates releases from the State prison or the San Francico County Jail. The project operates under contract with the San Francisco Sheriff’s Dept. New Options Initiative (January 2000 – present). The project provides technical assistance to selected counties on the development of innovative interventions and funding strategies for special needs youth in the juvenile justice system. Oakland Pathways to Change Project (2002 – 2004). Provides advocacy and intensive case management services for high risk Oakland youth who would otherwise be detained in the Alameda County Juvenile Hall. -

©2009 Hammett & Edison, Inc. TV Station KAEF • Analog Channel 23

TV Station KAEF • Analog Channel 23, DTV Channel 22 • Arcata, CA Expected Operation on June 13: Licensed Digital License (solid): 45.0 kW ERP at 550 m HAAT, Network: ABC vs. Analog (dashed): 141 kW ERP at 510 m HAAT, Network: ABC Market: Eureka, CA OR-4 NORTH Del Norte Crescent City Siskiyou CA-2 Etna Arcata A23 D22 Trinity Rio Dell Humboldt Shasta CA-1 Tehama Mendocino Glenn 2009 Hammett & Edison, Inc. Lake 10MI 0 10 20 30 40 50 100 80 60 40 20 0 KM 20 Coverage gained after DTV transition Analog service 91,108 persons Digital service 107,680 No symbol = no change in coverage Analog loss 80 Coverage lost after DTV transition Digital gain 16,652 Net gain 16,572 BLCDT-20071012ASQ Map set 1 KAEF Digital License TV Station KAEF • Analog Channel 23, DTV Channel 22 • Arcata, CA Approved Post-Transition Operation: Licensed Digital License (solid): 45.0 kW ERP at 550 m HAAT, Network: ABC vs. Analog (dashed): 141 kW ERP at 510 m HAAT, Network: ABC Market: Eureka, CA OR-4 NORTH Del Norte Crescent City Siskiyou CA-2 Etna Arcata A23 D22 Trinity Rio Dell Humboldt Shasta CA-1 Tehama Mendocino Glenn 2009 Hammett & Edison, Inc. Lake 10MI 0 10 20 30 40 50 100 80 60 40 20 0 KM 20 Coverage gained after DTV transition Analog service 91,108 persons Digital service 107,680 No symbol = no change in coverage Analog loss 80 Coverage lost after DTV transition Digital gain 16,652 Net gain 16,572 BLCDT-20071012ASQ Map set 2 KAEF Digital License TV Station KBVU • Analog Channel 29, DTV Channel 28 • Eureka, CA Expected Operation on June 13: Granted Construction Permit Digital CP (solid): 50.0 kW ERP at 513 m HAAT, Network: Fox vs. -

Presenting Station PBS Socal Los Angeles, CA February 21, 2021 @ 1:30Pm

Presenting Station PBS SoCal Los Angeles, CA February 21, 2021 @ 1:30pm Check all dates and times with your local provider, as schedules can change. Stations organized alphabetically by state. State California KPJK San Francisco, CA November 14 @ 8pm KQED San Francisco, CA November 20 @ 8pm November 21 @ 2am KQED-2 San Francisco, CA November 20 @ 8pm November 21 @ 2am November 26 @ 3pm KQET Monterey, CA November 21 @ 2am KPBS San Diego, CA November 23 @ 10pm KQET-2 Monterey, CA November 26 @ 3pm KQEH San Francisco, CA November 26 @ 3pm KEET Eureka, CA December 7 @ 1pm KCET Los Angeles, CA December 20 @ 4pm February 9 @ 2pm PBS SoCal Los Angeles, CA February 2 @ 9pm Connecticut WEDH Hartford, CT November 21 @ 11pm November 26 @ 5am WEDY-3 Hartford, CT November 21 @ 11pm November 26 @ 5am Florida WEFS Orlando, FL November 19 @ 8pm November 20 @ 12am WPBT Miami, FL December 28 @ 11pm December 30 @ 4am Georgia WPBA Atlanta, GA November 17 @ 11pm November 18 @ 4am Idaho WMAW Meridian, ID December 1 @ 3pm Indiana WUSI Terre Haute, IN December 20 @ 10am Iowa WQPT Davenport, IA December 13 @ 8pm December 14 @ 1am December 15 @ 11pm December 16 @ 4am Kansas KTWU-3 Topeka, KS November 22 @ 5am Kentucky WSIU Paducah, KY December 20 @ 10am Minnesota WSDE-2 Duluth, MN November 22 @ 9pm WRPT-2 Duluth, MN November 22 @ 9pm WDSE Duluth, MN December 11 @ 12am WRPT Duluth, MN December 11 @ 12am KTCA Minneapolis, MN December 13 @ 3pm December 18 @ 11pm December 19 @ 5am KSMQ Rochester, MN December 16 @ 8pm December 18 @ 12pm KTCI-3 Minneapolis, MN December -

Pedone, Ronald J. Status,Report on Public Broadcasting, 1973. Advanc

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 104 365 95 /R 001 757 AUTHOR Lee, S. Young; Pedone, Ronald J. TITLE Status,Report on Public Broadcasting, 1973. Advance Edition. Educational Technology Series. INSTITUTION Corporation for Public Broadcasting, Washington, D.C.; Nationil Cener for Education Statistics (DREW), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE Dec 74 NOTE 128p. EDRS PRICE MF-S0.76HC-66.97 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Annual Reports; Audiences; *Broadcast Industry; *Educational Radio; Educational Television; Employment Statistics; Financial Support; Media Research; Minority Groups; Programing (Broadcast); *Public Television; Statistical Studies; Tables (Data) IDENTIFIERS *Corporation for Public Broadcasting; CPB; PBS; Public Broadcasting Service ABSTRACT I statistical report on public broadcasting describes the status of the industry for 1973. Six major subject areas are covered: development of public broadcasting, finance, employment, broadcast and production, national interconnection services, and audiences of public broadcasting. Appendixes include supplementary tables showing facilities, income by source and state, percent distribution of broadcait hours, in-school broadcast hodrs, and listings of public radio and public television stations on the air as of June 30, 1973. There are 14 figures and 25 summary tables. (SK) A EDUCATIONAL TECHNOLOGY k STATUS REPORT ON I :I . PUBLIC BROADCASTING 1973 US DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH EDUCATION &WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO OUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM 14E PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGIN -

Federal Register/Vol. 86, No. 91/Thursday, May 13, 2021/Proposed Rules

26262 Federal Register / Vol. 86, No. 91 / Thursday, May 13, 2021 / Proposed Rules FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS BCPI, Inc., 45 L Street NE, Washington, shown or given to Commission staff COMMISSION DC 20554. Customers may contact BCPI, during ex parte meetings are deemed to Inc. via their website, http:// be written ex parte presentations and 47 CFR Part 1 www.bcpi.com, or call 1–800–378–3160. must be filed consistent with section [MD Docket Nos. 20–105; MD Docket Nos. This document is available in 1.1206(b) of the Commission’s rules. In 21–190; FCC 21–49; FRS 26021] alternative formats (computer diskette, proceedings governed by section 1.49(f) large print, audio record, and braille). of the Commission’s rules or for which Assessment and Collection of Persons with disabilities who need the Commission has made available a Regulatory Fees for Fiscal Year 2021 documents in these formats may contact method of electronic filing, written ex the FCC by email: [email protected] or parte presentations and memoranda AGENCY: Federal Communications phone: 202–418–0530 or TTY: 202–418– summarizing oral ex parte Commission. 0432. Effective March 19, 2020, and presentations, and all attachments ACTION: Notice of proposed rulemaking. until further notice, the Commission no thereto, must be filed through the longer accepts any hand or messenger electronic comment filing system SUMMARY: In this document, the Federal delivered filings. This is a temporary available for that proceeding, and must Communications Commission measure taken to help protect the health be filed in their native format (e.g., .doc, (Commission) seeks comment on and safety of individuals, and to .xml, .ppt, searchable .pdf). -

Humboldt State University System

HUMBOLDTHUMBOLDT STATESTATE UNIVERSITYUNIVERSITY 2007 LUMBERJACKS - FOOTBALL FOOTBALL SOFTBALL H HSU had a memorable 2006 Junior Lizzy Prescott and soph- season, recording a 9-1 record, omore Marissa Slattery and 2 the best mark since 1998. Senior Natalie Galletly were all named U DB Kyle Killingworth earned first All-Americans as the squad com- team All-American honors while piled a 55-6 overall record and a senior QB Blake Moorman be- 29-3 CCAA mark. The Lumber- 0 came HSU’s new career leader jacks claimed their eighth straight M in passing yardage. Also, senior conference title and 17th all-time DL Todd Eagle was selected to West Region appearance. 0 B the ESPN The Magazine Aca- demic All-America first team. 6 MEN’S CROSS COUNTRY WOMEN’S CROSS COUNTRY O Jimmy Elam and Omar Lion fin- HSU’s top five finished with an ished 9th and 12th, respectively, 18-second spread, leading to at the CCAA Championships, a fifth place team finish at the - L helping the Jacks to a 5th place CCAA women’s champion- team finish. Humboldt State’s ships. Leading the Lumberjacks team placed 11th overall in the was freshman Megan Rolland, 0 D men’s division at the NCAA Divi- who placed 18th place in a time sion II West Region Champion- of 24:03 on the 6-kilometer ships. Limon earned the Jacks’ course. HSU later finished 12th top individual place, finishing overall in the field of 18 at the DII 7 T 22nd. West Region Championships. MEN’S SOCCER WOMEN’S SOCCER Continuing to make huge strides HSU’s eight seniors led the way forward, the Lumberjacks turned in 2006, helping the Jacks to a in an 11-6-3 overall record and school record-tying 12 victories S a 7-6-3 CCAA mark. -

Information Ecosystem Assessment

EUREKA, CALIFORNIA, MAY-JULY 2019 INFORMATION ECOSYSTEM ASSESSMENT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY WHAT AM I READING? What follows is an assessment of the information ecosystem – the dynamic of information creation, distribution, and consumption – of Eureka, California. Eureka, (population 26,998) is the country seat and largest city of Humboldt County (population 136,373) located along California’s remote and rural northern coast. Humboldt is the home of Access Humboldt, a local non-profit, public access media network, and Internews, a global non-profit supporting healthy information worldwide. The purpose of this project is to inform Access Humboldt’s new strategic plan for 2020-2025, and to help Access Humboldt better serve the information needs of their evolving community. We will also provide a version of this report for the general public, particularly journalists, philanthropists, government officials, and the civil society and activist community for consideration in pursuit of their civic and policy goals. KEY FINDINGS For its size and level of wealth, Eureka has a diverse array of information sources. Eureka is one of the smallest media markets in the country (#195 of 205). Despite this, it enjoys a local newspaper of record, an alternative weekly, two network affiliates with local news broadcasts, a PBS affiliate, two commercial local news sources, and a host of commer- cial and community radio stations. With the notable exception of the sudden closure of KHSU, the local NPR affiliate hosted by Humboldt State University, Eureka’s market has remained remarkably stable. Eurekans generally have access to an information source they trust. The vast majority of the people we talked to,- both in and outside the media industry, agreed there were multiple trustworthy news opera tions. -

37 Annual NORTHERN CALIFORNIA AREA EMMY® AWARDS PRESENTED

th 37 Annual NORTHERN CALIFORNIA AREA EMMY® AWARDS PRESENTED th th The 37 Annual Northern California Area EMMY® Awards were presented Saturday evening, May 10 at the Palace of Fine Arts in San Francisco. The Emmy® Award honors excellence in all fields of television production. Hawaii took top honors with Station Excellence going to KGMB 9 and News Excellence to KHNL 8. Community Service had two winners: KQED 9 Public Broadcasting, San Francisco and KSTS Telemundo 48, San Jose. The Large Market Newscast recipients were “CBS 5 Eyewitness News at 11PM,” KPIX CBS 5, San Francisco and “NBC11's The Bay Area Today at 11AM,” KNTV NBC 11, San Jose. Medium Market Newscasts went to “KGMB 9 News at 10PM,” KGMB 9 Honolulu and “Action News AM Live,” KFSN ABC 30, Fresno. KTVN 2 Reno took both Smaller Market Newscasts: “Channel 2 News at 6:30PM,” and “Channel 2 News This Morning.” KUVS Unvision 19 took received 13 awards followed by KPIX CBS 5 and KNTV NBC 11 with eleven each. The most honored individual was Santiago Lucero, Reporter KUVS Univison19, Sacramento, who took home five statuettes. Closely followed by Investigative Reporter, Anna Werner, KPIX CBS 5, San Francisco and Albert Garcia, Photographer, KUVS Univision 19, Sacramento with four each. The total of 227 statues went to 184 individuals this year. KUVS Univision 19 in Sacramento was the top station winner with 13 awards followed by a tie with 11 awards each for KPIX CBS 5, San Francisco and KNTV NBC 11, San Jose. The Emmy® is awarded for outstanding achievement in Television by The National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences. -

530 CIAO BRAMPTON on ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb

frequency callsign city format identification slogan latitude longitude last change in listing kHz d m s d m s (yy-mmm) 530 CIAO BRAMPTON ON ETHNIC AM 530 N43 35 20 W079 52 54 09-Feb 540 CBKO COAL HARBOUR BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N50 36 4 W127 34 23 09-May 540 CBXQ # UCLUELET BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 56 44 W125 33 7 16-Oct 540 CBYW WELLS BC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N53 6 25 W121 32 46 09-May 540 CBT GRAND FALLS NL VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 57 3 W055 37 34 00-Jul 540 CBMM # SENNETERRE QC VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N48 22 42 W077 13 28 18-Feb 540 CBK REGINA SK VARIETY CBC RADIO ONE N51 40 48 W105 26 49 00-Jul 540 WASG DAPHNE AL BLK GSPL/RELIGION N30 44 44 W088 5 40 17-Sep 540 KRXA CARMEL VALLEY CA SPANISH RELIGION EL SEMBRADOR RADIO N36 39 36 W121 32 29 14-Aug 540 KVIP REDDING CA RELIGION SRN VERY INSPIRING N40 37 25 W122 16 49 09-Dec 540 WFLF PINE HILLS FL TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 93.1 N28 22 52 W081 47 31 18-Oct 540 WDAK COLUMBUS GA NEWS/TALK FOX NEWSRADIO 540 N32 25 58 W084 57 2 13-Dec 540 KWMT FORT DODGE IA C&W FOX TRUE COUNTRY N42 29 45 W094 12 27 13-Dec 540 KMLB MONROE LA NEWS/TALK/SPORTS ABC NEWSTALK 105.7&540 N32 32 36 W092 10 45 19-Jan 540 WGOP POCOMOKE CITY MD EZL/OLDIES N38 3 11 W075 34 11 18-Oct 540 WXYG SAUK RAPIDS MN CLASSIC ROCK THE GOAT N45 36 18 W094 8 21 17-May 540 KNMX LAS VEGAS NM SPANISH VARIETY NBC K NEW MEXICO N35 34 25 W105 10 17 13-Nov 540 WBWD ISLIP NY SOUTH ASIAN BOLLY 540 N40 45 4 W073 12 52 18-Dec 540 WRGC SYLVA NC VARIETY NBC THE RIVER N35 23 35 W083 11 38 18-Jun 540 WETC # WENDELL-ZEBULON NC RELIGION EWTN DEVINE MERCY R. -

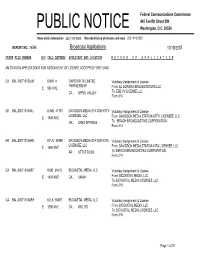

Broadcast Applications 10/19/2007

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 26595 Broadcast Applications 10/19/2007 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING CA BAL-20071015AJW KIXW 4 CAPSTAR TX LIMITED Voluntary Assignment of License PARTNERSHIP E 960 KHZ From: EL DORADO BROADCASTERS LLC CA , APPLE VALLEY To: EDB VV LICENSE LLC Form 316 OK BAL-20071015AKJ KJMU 47101 DAVIDSON MEDIA STATION KTFX Voluntary Assignment of License LICENSEE, LLC E 1340 KHZ From: DAVIDSON MEDIA STATION KTFX LICENSEE, LLC OK , SAND SPRINGS To: BIRACH BROADCASTING CORPORATION Form 314 AR BAL-20071015AKK KTUV 34988 DAVIDSON MEDIA STATION KITA Voluntary Assignment of License LICENSEE, LLC E 1440 KHZ From: DAVIDSON MEDIA STATION KITA LICENSEE, LLC AR , LITTLE ROCK To: BIRACH BROADCASTING CORPORATION Form 314 CA BAL-20071016ABF KUKI 31619 BICOASTAL MEDIA, LLC Voluntary Assignment of License E 1400 KHZ CA , UKIAH From: BICOASTAL MEDIA, LLC To: BICOASTAL MEDIA LICENSES, LLC Form 316 CA BAL-20071016ABH KLLK 65697 BICOASTAL MEDIA, LLC Voluntary Assignment of License E 1250 KHZ CA , WILLITS From: BICOASTAL MEDIA, LLC To: BICOASTAL MEDIA LICENSES, LLC Form 316 Page 1 of 21 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO.