Döner Kebab and West German Consumer (Multi-)Cultures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Private Party Packages

PRIVATE PARTY PACKAGES BEVERAGE OPTIONS [3 HOURS] Shots and martinis not included. Drink package prices do not include gratuity. PACKAGE #1 PACKAGE #2 PACKAGE #3 $22/person $27/person $34/person Domestic Bottles Imported, Craft and Imported, Craft and Miller Lite Drafts Domestic Bottles Domestic Bottles INCLUDING PREMIUM IMPORTS All Draft Beers Wine All Draft Beers Wine House Liquors Premium Wine Premium Liquors Top Shelf Liquors CASH BAR HOST BAR Each party guests purchases their Host is charged based on own beverages. Minimums apply. consumption. Minimums apply. FOOD TRAYS Mini Cheeseburgers (20 CT.)...................$40 Flatbreads ..................................... EACH $6 (30 CT.) .................$60 (4 OPTIONS: 1. PROSCIUTTO, MOZZARELLA & TRUFFLE OIL; 2. SMOKED CHICKEN, GUINNESS BBQ SAUCE; 3. MOZZARELLA, BASIL & TOMATO 4.BUFFALO CHICKEN, BUFFALO BLEU SAUCE, Buffalo Chicken Wings (40 CT.) ...............$45 (SIRACHA BBQ, BUFFALO OR GUINNESS BBQ) ROASTED CELERY) Quesadilla (30 PIECES) ...............................$50 Assorted Cheeses, Cracker (STEAK, CHICKEN OR VEGETABLE) and Fruit Tray (SERVES UP TO 20) .....................$60 Bone-in Short Rib Bites (40 CT) ...............$45 Hummus & Vegetable Tray ...............$50 Soft Pretzel Sticks (20 CT.) .......................$40 (SERVES UP TO 20) Wisconsin Cheese Curds (SERVES UP TO 20) ...$45 Mac & Cheese Tray (SERVES UP TO 20) ............$65 Chips & Salsa (SERVES UP TO 20) .....................$30 French Fries/Tator Tots/Sweet Potato with Guacamole ............................$70 -

Nos Formules Sandwichs Nos Formules Paninis Nosformules Salades

Des fri!es Une boisson Une boisson Un sandwich Nos formules sandwichs Un sandwich SANDWICHS + FRITES + BOISSON PANINI+BOISSONNos formules Paninis Sur ½ Baguette, Pain Rond ou en Wrap •HAMBURGER 1 11,90€ •VEGAN BURGER 1 14,90€ •ITALIEN 1.7 7,50€ •POULET 1.7 7,50€ Steak haché frais pur bœuf, oignons rôtis, salade,tomates. Steak de légumes, oignons rôtis, galette PDT, Jambon de parme, mozzarella, basilic, Poulet pané, mozzarella, tomates, huile d’olive. guacamole, salade, tomates. tomates, huile d’olive. •CHEESE BURGER 1.7 12,90€ •THON 1.4.7 7,50€ Steak haché frais pur bœuf, oignons rôtis, •JAMBON FROMAGE 1.7 7,50€ Thon, emmental, tomates, basilic, mayonnaise. cheddar, salade, tomates. •FORESTIER 1.7 15,90€ Jambon, emmental, tomates. Steak haché frais pur bœuf, oignons rôtis, lard, •CHICKEN BURGER 1.7 14,50€ emmental, champignons, crème. Filet de poulet pané, oignons rôtis, cheddar, salade, tomates. •BIFANA 1 11,90€ Escalope de porc mariné, oignons rôtis, salade, tomate. •BACON BURGER 1.7 14,50€ Steak haché frais pur bœuf, oignons rôtis, bacon, Nos boissons (33cl) cheddar, salade, tomates. •BIFANA SPECIAL 1.3.7 14,50€ Saucisse,Nos sauce saucisses au choix. Escalope de porc mariné, oignons rôtis, jambon, bacon, •HOUSE BURGER 1.3.7 16,50€ fromage, œuf, salade, tomates. •METTWURST 1 3,90€ •COCA-COLA (NORMAL, ZÉRO), Steak haché frais pur bœuf, oignons rôtis, bacon, Saucisse, sauce au choix. jambon, œuf, cornichons, cheddar, salade, tomates. •TARTUFO 1.7 17,50€ FANTA, SPRITE, ICE TEA, EAU 3,00€ Steak haché pur bœuf, crème de truffe, oignons rotis, •GRILLWURST 1 3,90€ •GALETTE BURGER 1.7 15,50€ •RED BULL 3,50€ Steak haché frais pur bœuf, oignons rôtis, bacon, comté, salade,tomates. -

Donairstory1.Pdf

The donairStreet has become a staple of late-night dining, butTreat what explains the allure of this tightly wound delicacy? The inside story of Calgary’s favourite mystery meat. by Omar Mouallem photography by Marnie Persaud n the summer of 2006 when I moved back to Alberta, an E. coli But in 2006, I wasn’t returning for a lucrative oil job. After two outbreak sent nine people to the hospital. It didn’t take too long years of college in Vancouver, plus another year spent drifting, I was I to nab the culprit: the donair—Canada’s version of Turkey’s döner kebab, Greece’s gyro, the Middle East’s shawarma, Mexico’s tacos al pastor. The delicious and devious meat on a spit that only seems to grill when I was 10. Nobody in High Prairie, the lesser of the Lesser beckon after midnight or on your most stressful days. Slave Lake communities where I grew up, had tried “that Lebanese The Oilers had advanced to the Stanley Cup Final. Fans poured thing” before my dad put it on his menu. But today at least four res- out of bars seeking that insidious food; vendors, unable to meet de- mand, began to shave the loaves too fast and served half-cooked slices since moved to Edmonton and, although I was bummed to have lost of a contaminated batch. This is how I knew I was home. It wasn’t the ensuing hockey riots. Mike Horwich also remembers the summer of 2006 well. He was sit- It was the dish that somehow manages to be both ubiquitous and curi- ting on Health Canada’s implausibly named Federal-provincial-territorial ously regional. -

Alyonka Russian Cuisine Menu

ZAKOOSKI/COLD APPETIZERS Served with your choice of toasted fresh bread or pita bread “Shuba” Layered salad with smoked salmon, shredded potatoes, carrots, beets and with a touch of mayo $12.00 Marinated carrot or Mushroom salad Marinated with a touch of white vinegar and Russian sunflower oil and spices $6.00 Smoked Gouda spread with crackers and pita bread $9.00 Garden Salad Organic spring mix, romaine lettuce, cherry tomatoes, cucumbers, green scallions, parsley, cranberries, pine nuts dressed in olive oil, and balsamic vinegar reduction $10.00. GORIYACHIE ZAKOOSKI/HOT APPETIZERS Chebureki Deep-fried turnover with your choice of meat or vegetable filling $5.00 Blini Russian crepes Four plain with sour cream, salmon caviar and smoked salmon $12.00 Ground beef and mushrooms $9.00 Vegetable filling: onion, carrots, butternut squash, celery, cabbage, parsley $9.00 Baked Pirozhki $4.00 Meat filling (mix of beef, chicken, and rice) Cabbage filling Dry fruit chutney Vegetarian Borscht Traditional Russian soup made of beets and garden vegetables served with sour cream and garlic toast Cup $6.00 Bowl $9.00 Order on-line for pickup or delivery 2870 W State St. | Boise | ID 208.344.8996 | alyonkarussiancuisine.com ENTREES ask your server for daily specials Beef Stroganoff with choice of seasoned rice, egg noodles, or buckwheat $19.95 Pork Shish Kebab with sauce, seasoned rice and marinated carrot salad $16.95 Stuffed Sweet Pepper filled with seasoned rice and ground beef $16.95 Pelmeni Russian style dumplings with meat filling served with sour cream $14.95 -

Form the Five Core Valu

Intr o The original Lebanese Dining Experience in Singapore since 2009 Food | Fun | Fusion | Friends | Family - form the five core values that complete the “Beirut Grill Experience.” At Beirut Grill, we place our customers as the highest priority in line with an alluring dining experience enhanced with serving good and healthy food in a warm and relaxed atmosphere. Your servers, referred to as 'Genies' , work passionately with the motto; “Your wish is Our command”. Lebanese Food is unique in that it combines the sophistication and subtleties of European haute cuisines with exotic ingredients of the orient and yet it is remarkable in its simplicity. Try the crown of Lebanese food - “MEZZA” (starters / antipasti/ tapas) infused with olive oil , herbs, brought in from the finest shops in Beirut. Great for sharing and getting a conversation started, it’s best enjoyed with our freshly baked breads. Your gastronomic journey continues with the mains featuring our award winning “Beirut Lamb Chops” & try our variety of Kebabs with Signature “Mixed Grill latter” and top off your meal with the sweet taste of “Baklava” With open hearts and smiles , we welcome you to Beirut Grill. “Your WISH is Our command” Beirut Grill | 72 Bussorah Street (S)199485 | Tel : +65 63417728 IG : beirutgrill_sg | F : Beirut Grill Fine Middle Eastern Cuisine | www.beirut.com.sg *Price subjected to taxes Star ter s Lentil Soup $7.00 Halloumi Salad Soup of the Day $19.00 $7.00 Mix of fresh vegetables Please ask our genie for mixed with cubes of halloumi today’s special. -

Zh New Menu PAGES 2 & 3 2-23-17

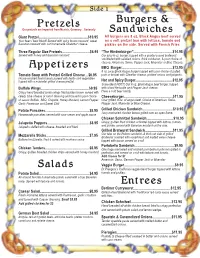

Our pretzels are imported from Munich, Germany…Seriously Giant Pretzel.....................................................$10.95 All burgers are 8 oz. Black Angus beef served Your beers’ best friend! Served with spicy brown mustard, sweet on a soft pretzel bun with lettuce, tomato and Bavarian mustard with our homemade Obatzda* cheese. pickles on the side. Served with French Fries. Three Regular Size Pretzels..............................$6.95 “The Hindenburger”..........................................$14.95 Served with honey and Bavarian mustard Our juicy 8 oz. burger, topped with a quarter pound bratwurst smothered with sautéed onions, thick cut bacon, & your choice of cheese. American, Swiss, Pepper Jack, Muenster or Blue Cheese. BBQ Burger.......................................................$13.95 8 oz. juciy Black Angus burger topped with your choice of pulled Tomato Soup with Pretzel Grilled Cheese ...$6.95 pork or brisket with Cheddar cheese, pickled onions and jalapeňo. House smoked fresh tomato pureed with herbs and vegetables topped with a muenster grilled cheese pretzel. Hot and Spicy Burger........................................$12.95 Some like it HOT!!! Our 8 oz. Black Angus beef burger, topped Buffalo Wings....................................................$9.95 with sliced Andouille and Pepper Jack cheese. Crispy hand breaded jumbo wings fried golden brown served with Have a cold beer handy. celery, blue cheese or ranch dressing and tossed in your choice Cheeseburger.....................................................$11.95 of sauce: Buffalo, BBQ, Chipotle, Honey Mustard, Lemon Pepper, Char grilled, 8 oz. of angus beef. Choice of American, Swiss, Garlic Parmesan and Sweet Chili Pepper Jack, Muenster or Blue Cheese. Potato Pancakes................................................$5.95 Grilled Chicken Sandwich.................................$10.95 Juicy marinated chicken breast grilled over an open flame. Homemade pancakes served with sour cream and apple sauce. -

Order Online

WRAPS & SANDWICHES DESSERTS All wraps/sandwiches are served with pita bread, $ lettuce, tomato, onion and tahini sauce. Kurdish Baklava (2 pieces) | 5.50 Ask for Gluten Free, Vegan and Vegetarian options. Layers of filo dough and pistachios in our home-made syrup Kazandibi (gf) | $5.50 Lamb & Beef Gyros Wrap | $10.95 Milk Pudding baked and caramelized Slow cooked, thin-sliced, marinated lamb & beef Kunefe | $7.50 Chicken Gyros Wrap | $10.95 Sweet shredded filo dough stuffed with salt-less cheese and A family owned and operated business Slow cooked, thin-sliced, pistachios serving delicious authentic flavors from the marinated chicken ORDER Rice Pudding (gf) | $5.00 ORDER Rice, milk, organic sugar, vanilla bean and cinnamon Mediterranean Coast to the Middle East. $ Adana Kebab Wrap | 10.95 ONLINE Decadent Chocolate Cake $7.00 Skewered charcoal grilled minced ONLINE-@ | sfkebab.--------@-------- New York Cheese Cake $7.00 Take Out, Catering lamb with fresh parsley, red onion com | and a touch of hot chili sfkebab.com Ice Cream | $5.50 ORDERORDER & Banquet Room available. Call (415) 255-2262 for Kofta Wrap | $10.95 ONLINEONLINE-@ -------- Minced beef with parsley and sumac onion WEEKEND BRUNCH -@com information. Served until 3PM sfkebab.------- Monday – Friday Salmon Wrap | $12.95 All egg dishes (except Breakfast Wrap) served with rosemary sfkebab.com Skewered charcoal grilled salmon with fresh tomato, roasted red potatoes, fresh fruit and home-made bread 11:00 a.m. to 9:00 p.m. lettuce and onion Mellemen (veg/gf) | $13.95 SF Kebab Mediterranean -

Demi's Dinner Entree

PASTICHIO seasoned ground beef with pasta noodles topped with béchamel and baked 16 ITALIAN MEATBALLS AND LINGUINI with marinara 16 GRILLED SALMON PUTTANESCA country tomato sauce with onions, garlic, PASTA peppers, capers, and olives over penne pasta 20 SUN-DRIED TOMATO, CAPERS & ARTICHOKE HEARTS sautéed with garlic olive oil and linguini 15 GREEK PASTA linguini, caramelized onions & olive oil tossed with imported feta 15 GORGONZOLA AND PEAS penne pasta sauteed with gorgonzola cheese and peas 16 GRILLED SWEET ITALIAN SAUSAGE over linguini with marinara and a dollop of ricotta cheese 16 SERVED OVER RICE PILAF WITH TZATZIKI PORK SOUVLAKI marinated pork tenderloin, onions and peppers 15 CHICKEN SOUVLAKI marinated chicken breast, onions and peppers 15 ADANA KEBAB ground lamb and spices skewered and grilled 15 KABOBS ALL SERVED WITH ONE SIDE OR OVER PASTA PORK MARSALA sautéed pork tenderloin cutlets with mushrooms and marsala wine 18 CHICKEN PICCATA sautéed chicken with lemon garlic caper sauce 18 GRILLED DOUBLE LAMB CHOPS with garlic, tomatoes, lemon, white wine and olive oil. 36 GRILLED SALMON topped with sautéed fresh garlic olive oil lemon and spinach 20 ENTREES SHRIMP SANTORINI sautéed with fresh garlic tomato herbs and feta 22 CALAMARI sautéed with white beans and arugula 20 SAUTÉED SHRIMP AND CHORIZO with white beans 20 GRILLED SALMON with sun-dried tomato caper relish 20 WHOLE FISH mkt RICE PILAF 6 PENNE & MARINARA 8 YAHNI GREEK GREEN BEANS 5 SIDES ROASTED POTATOES 6 ROASTED GARLIC MASHED POTATOES 5 GIGANTES giant greek white beans cooked in tomato sauce 6 SAUTÉED ARTICHOKES & PEAS 6 HOUSE SALAD 6, substitute one side with entrée 4 10 AND UNDER LINGUINI OR PENNE marinara, butter or olive oil 8 KIDS with meatball or chicken 12 KABOB PORK, CHICKEN OR ADANA with rice pilaf 10 Notice: Consuming raw or undercooked meats, poultry, seafood, shellfish, or eggs may increase your risk of foodborne illness. -

Around the World in 80 Food Trucks 1 Preview

Lobster mac ‘n’ cheese, BOB’s Lobster 26 Buttermilk-fried-chicken biscuit OCEANIA SOUTH AMERICA Newport bowl with tofu, Califarmication 144 Great balls of fire pork & beef meatballs, sandwiches, Humble Pie 56 Detox açai bowl, Açai Corner 82 Peruvian sacha taco, Hit ‘n Run 110 BEC sandwich, Paperboy 146 contents The Bowler 28 Super cheddar burger, Paneer 58 Carolina smoked pulled pork sandwich, The Cajacha burger, Lima Sabrosa 112 The Viet banh mi, Chicago Lunchbox 148 Goat’s cheese, honey & walnut Turkey burger, Street Chefs 60 Sneaky Pickle 84 Yakisoba bowl, Luca China 114 Blue cheese slaw, Banjo's 150 Introduction 5 toasted sandwich, The Cheese Truck 30 Forest pancake, Belki&Uglevody 62 The Bahh lamb souvlaki, Argentine sandwich, El Vagabundo 116 Old-fashioned peach cake, The Peach Truck 152 Jerusalem spiced chicken, Laffa 32 Greek Street Food 86 Uruguayan flan, Merce Daglio Sweet Truck 118 Alabama tailgaters, Fidel Gastro’s 154 EUROPE Fried chicken, Mother Clucker 34 AFRICA & MIDDLE EAST Mr Chicken burger, Mr Burger 88 Tapioca pancake, Tapí Tapioca 120 Nanner s’more, Meggrolls 156 Spicy Killary lamb samosas, Chicken, chilli & miso gyoza, Rainbo 36 South African mqa, 4Roomed eKasi Culture 64 Tuscan beef ragu, Pasta Face 90 Red velvet cookies, Misunderstood Heron 6 Asparagus, ewe’s cheese, mozzarella & Asian bacon burger, Die Wors Rol 66 The Fonz toastie, Toasta 92 NORTH AMERICA Captain Cookie and the Milk Man 158 San Francisco langoustine roll, hazelnut pizza, Well Kneaded 38 Chicken tikka, Hangry Chef 68 Butter paneer masala, Yo India -

BKM Latest Issue

SEE A BIGGER PICTURE NEW LEXUS RX SELF-CHARGING HYBRID PER £483 + VAT MONTH* £2,898 + VAT INITIAL RENTAL* LEXUS EDGWARE ROAD The Hyde, Edgware Road NW9 6NW 020 8358 2258 www.lexus.co.uk/edgware-road Model shown is RX F SPORT (£55,205) including solid paint. Exact fuel consumption figures for model shown in mpg (l/100km) combined: 35.7 (7.9) and CO2: 134 g/km. RX model range in mpg (l/100km) official fuel consumption figures: combined 35.3 (8.0) – 35.7 (7.9). Figures are provided for comparative purposes; only compare fuel consumption and2 COfigures with other cars tested to the same technical procedures. These figures may not reflect real life driving results. All mpg figures quoted are full WLTP figures. All2 CO figures quoted are NEDC equivalent. CO2 figures (and hence car tax and recommended ‘on the road’ prices) subject to change for new vehicles registered after 6 April 2020, due to a change in the official method of calculation. Find out more about WLTP at www.lexus.co.uk/WLTP#eco-hero or contact your local Lexus Centre. *Business users only. Initial rental and VAT applies. Available on new leases of RX F SPORT when ordered and proposed for finance between 17th December 2019 and 31st March 2020, registered and financed by 30th June 2020 through Lexus Financial Services on Lexus Contract Hire. Advertised rental is based on a 48 month customer maintained contract at 8,000 miles per annum with an initial rental of £2,898 +VAT. Excess mileage charges apply. -

An Exploratory Study Linking Turkish Regional Food with Cultural Destinations

Academica Turistica Discussions An Exploratory Study Linking Turkish Regional Food with Cultural Destinations Mehmet Ergul San Francisco State University College of Business, Hospitality and Tourism Management Department [email protected] Colin Johnson San Francisco State University College of Business, Hospitality and Tourism Management Department [email protected] Ali Sukru Cetinkaya Selcuk University Vocational School of Silifke Tasucu, Turkey [email protected] Jale Boga Robertson Blue Odyssey Corte Madera, CA [email protected] Abstract Food and tourism may be considered as two interrelated elements that bring people and cultures together on many different occasions. Research indicates that food could be viewed as a peak touristic experience and a major tourist attraction. The main purpose of this paper is to identify and evaluate the significance of food tour- ism for Turkey and to create a number of innovative regional food related itineraries that would be replicable. Four main results emerged from the analysis of the interviews. The major recommendations from the study include developing an action list for the Turkish Ministry of Tourism, developing new food tourism itineraries and creating an official food guide. The findings of the study could be used as a base for further exploring the application of new technologies in food destination sectors. Key words: Food tourism, Turkey, regional cuisines, innovation Academica Turistica, Year 4, No. 2, December 2011 | 101 Academica Turistica_ok.indd 101 2.2.2012 17:56:28 Mehmet Ergul, Colin Johnson, Ali Sukru Cetinkaya, Jale Boga Robertson An Exploratory Study ... Introduction in the economy at the local, regional, national and international levels. Food and tourism may be considered as two inter- Being seen as one of the most important “pull” fac- related elements which bring people and cultures tors in the literature, a destination’s image is known together in many different ways. -

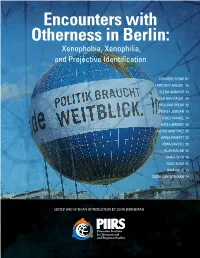

Encounters with Otherness in Berlin: Xenophobia, Xenophilia, and Projective Identification

Encounters with Otherness in Berlin: Xenophobia, Xenophilia, and Projective Identification CONTRIBUTIONS BY ZARTOSHT AHLERS ‘18 ELENA ANAMOS ‘19 LEILA BEN HALIM. ‘20 WILLIAM GREAR ‘20 SYDNEY JORDAN ‘19 EMILY KUNKEL ‘19 NATE LAMBERT ‘20 ALEXIA MARTINEZ ‘20 APRIA PINKETT ‘20 IRMA QAVOLLI ‘20 ALAA RAGAB ‘20 RAINA SEYD ‘19 YANG SHAO ‘20 SAM VALLE ‘19 SADIE VAN VRANKEN ’19 : EDITED AND WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY JOHN BORNEMAN © 2017 Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies With special thanks to the Department of Anthropology, Princeton University. COVER PHOTO: “There was a big hot air balloon that we passed that said “politics needs a worldview” in German. I liked this message. It was a comforting first impression.” - Emily Kunkel TABLE OF CONTENTS PROFESSOR JOHN BORNEMAN APRIA PINKETT ’20 Introduction . 3 German Culture: The Most Exclusive Club . 44 ZARTOSHT AHLERS ’18 German Culture in Three Words: Beer, Currywurst, and Money . 62 Leopoldplatz . 7 Bergmann Burger: There’s No Place Encounter With a Turkish Like Home . 79 Immigrant at Leopoldplatz . 12 Ich Spreche Englisch . 85 Movement . 25 So Loud . 88 IRMA QAVOLLI ’20 ELENA ANAMOS ’19 An Unexpected Conversation . 17 Cultural Belonging: Belonging: Body Language Childbearing and Channel Surfing: in a Conversation on Foreignness . 23 A Reunion with My Family . 40 A Market Conversation . 48 An Encounter Over Ice Cream Food . 69 in Leopoldplatz . 71 The Language Barrier in Hermannplatz . 83 ALAA RAGAB ’20 JOHN BENJAMIN, LANGUAGE INSTRUCTOR Let’s Test You for Explosives Residue! . .19 Arab is Better, Arab is More Fun . 28 Language: Change in Global Seminars . 82 Germans Nice or Nein? .