Encounters with Otherness in Berlin: Xenophobia, Xenophilia, and Projective Identification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Private Party Packages

PRIVATE PARTY PACKAGES BEVERAGE OPTIONS [3 HOURS] Shots and martinis not included. Drink package prices do not include gratuity. PACKAGE #1 PACKAGE #2 PACKAGE #3 $22/person $27/person $34/person Domestic Bottles Imported, Craft and Imported, Craft and Miller Lite Drafts Domestic Bottles Domestic Bottles INCLUDING PREMIUM IMPORTS All Draft Beers Wine All Draft Beers Wine House Liquors Premium Wine Premium Liquors Top Shelf Liquors CASH BAR HOST BAR Each party guests purchases their Host is charged based on own beverages. Minimums apply. consumption. Minimums apply. FOOD TRAYS Mini Cheeseburgers (20 CT.)...................$40 Flatbreads ..................................... EACH $6 (30 CT.) .................$60 (4 OPTIONS: 1. PROSCIUTTO, MOZZARELLA & TRUFFLE OIL; 2. SMOKED CHICKEN, GUINNESS BBQ SAUCE; 3. MOZZARELLA, BASIL & TOMATO 4.BUFFALO CHICKEN, BUFFALO BLEU SAUCE, Buffalo Chicken Wings (40 CT.) ...............$45 (SIRACHA BBQ, BUFFALO OR GUINNESS BBQ) ROASTED CELERY) Quesadilla (30 PIECES) ...............................$50 Assorted Cheeses, Cracker (STEAK, CHICKEN OR VEGETABLE) and Fruit Tray (SERVES UP TO 20) .....................$60 Bone-in Short Rib Bites (40 CT) ...............$45 Hummus & Vegetable Tray ...............$50 Soft Pretzel Sticks (20 CT.) .......................$40 (SERVES UP TO 20) Wisconsin Cheese Curds (SERVES UP TO 20) ...$45 Mac & Cheese Tray (SERVES UP TO 20) ............$65 Chips & Salsa (SERVES UP TO 20) .....................$30 French Fries/Tator Tots/Sweet Potato with Guacamole ............................$70 -

Nos Formules Sandwichs Nos Formules Paninis Nosformules Salades

Des fri!es Une boisson Une boisson Un sandwich Nos formules sandwichs Un sandwich SANDWICHS + FRITES + BOISSON PANINI+BOISSONNos formules Paninis Sur ½ Baguette, Pain Rond ou en Wrap •HAMBURGER 1 11,90€ •VEGAN BURGER 1 14,90€ •ITALIEN 1.7 7,50€ •POULET 1.7 7,50€ Steak haché frais pur bœuf, oignons rôtis, salade,tomates. Steak de légumes, oignons rôtis, galette PDT, Jambon de parme, mozzarella, basilic, Poulet pané, mozzarella, tomates, huile d’olive. guacamole, salade, tomates. tomates, huile d’olive. •CHEESE BURGER 1.7 12,90€ •THON 1.4.7 7,50€ Steak haché frais pur bœuf, oignons rôtis, •JAMBON FROMAGE 1.7 7,50€ Thon, emmental, tomates, basilic, mayonnaise. cheddar, salade, tomates. •FORESTIER 1.7 15,90€ Jambon, emmental, tomates. Steak haché frais pur bœuf, oignons rôtis, lard, •CHICKEN BURGER 1.7 14,50€ emmental, champignons, crème. Filet de poulet pané, oignons rôtis, cheddar, salade, tomates. •BIFANA 1 11,90€ Escalope de porc mariné, oignons rôtis, salade, tomate. •BACON BURGER 1.7 14,50€ Steak haché frais pur bœuf, oignons rôtis, bacon, Nos boissons (33cl) cheddar, salade, tomates. •BIFANA SPECIAL 1.3.7 14,50€ Saucisse,Nos sauce saucisses au choix. Escalope de porc mariné, oignons rôtis, jambon, bacon, •HOUSE BURGER 1.3.7 16,50€ fromage, œuf, salade, tomates. •METTWURST 1 3,90€ •COCA-COLA (NORMAL, ZÉRO), Steak haché frais pur bœuf, oignons rôtis, bacon, Saucisse, sauce au choix. jambon, œuf, cornichons, cheddar, salade, tomates. •TARTUFO 1.7 17,50€ FANTA, SPRITE, ICE TEA, EAU 3,00€ Steak haché pur bœuf, crème de truffe, oignons rotis, •GRILLWURST 1 3,90€ •GALETTE BURGER 1.7 15,50€ •RED BULL 3,50€ Steak haché frais pur bœuf, oignons rôtis, bacon, comté, salade,tomates. -

Foods with an International Flavor a 4-H Food-Nutrition Project Member Guide

Foods with an International Flavor A 4-H Food-Nutrition Project Member Guide How much do you Contents know about the 2 Mexico DATE. lands that have 4 Queso (Cheese Dip) 4 Guacamole (Avocado Dip) given us so 4 ChampurradoOF (Mexican Hot Chocolate) many of our 5 Carne Molida (Beef Filling for Tacos) 5 Tortillas favorite foods 5 Frijoles Refritos (Refried Beans) and customs? 6 Tamale loaf On the following 6 Share a Custom pages you’ll be OUT8 Germany taking a fascinating 10 Warme Kopsalat (Wilted Lettuce Salad) 10 Sauerbraten (German Pot Roast) tour of four coun-IS 11 Kartoffelklösse (Potato Dumplings) tries—Mexico, Germany, 11 Apfeltorte (Apple net) Italy, and Japan—and 12 Share a Custom 12 Pfefferneusse (Pepper Nut Cookies) Scandinavia, sampling their 12 Lebkuchen (Christmas Honey Cookies) foods and sharing their 13 Berliner Kränze (Berlin Wreaths) traditions. 14 Scandinavia With the helpinformation: of neigh- 16 Smorrebrod (Danish Open-faced bors, friends, and relatives of different nationalities, you Sandwiches) 17 Fisk Med Citronsauce (Fish with Lemon can bring each of these lands right into your meeting Sauce) room. Even if people from a specific country are not avail- 18 Share a Custom able, you can learn a great deal from foreign restaurants, 19 Appelsinfromage (Orange Sponge Pudding) books, magazines, newspapers, radio, television, Internet, 19 Brunede Kartofler (Brown Potatoes) travel folders, and films or slides from airlines or your local 19 Rodkal (Pickled Red Cabbage) schools. Authentic music andcurrent decorations are often easy 19 Gronnebonner i Selleri Salat (Green Bean to come by, if youPUBLICATION ask around. Many supermarkets carry a and Celery Salad) wide choice of foreign foods. -

China in 50 Dishes

C H I N A I N 5 0 D I S H E S CHINA IN 50 DISHES Brought to you by CHINA IN 50 DISHES A 5,000 year-old food culture To declare a love of ‘Chinese food’ is a bit like remarking Chinese food Imported spices are generously used in the western areas you enjoy European cuisine. What does the latter mean? It experts have of Xinjiang and Gansu that sit on China’s ancient trade encompasses the pickle and rye diet of Scandinavia, the identified four routes with Europe, while yak fat and iron-rich offal are sauce-driven indulgences of French cuisine, the pastas of main schools of favoured by the nomadic farmers facing harsh climes on Italy, the pork heavy dishes of Bavaria as well as Irish stew Chinese cooking the Tibetan plains. and Spanish paella. Chinese cuisine is every bit as diverse termed the Four For a more handy simplification, Chinese food experts as the list above. “Great” Cuisines have identified four main schools of Chinese cooking of China – China, with its 1.4 billion people, has a topography as termed the Four “Great” Cuisines of China. They are Shandong, varied as the entire European continent and a comparable delineated by geographical location and comprise Sichuan, Jiangsu geographical scale. Its provinces and other administrative and Cantonese Shandong cuisine or lu cai , to represent northern cooking areas (together totalling more than 30) rival the European styles; Sichuan cuisine or chuan cai for the western Union’s membership in numerical terms. regions; Huaiyang cuisine to represent China’s eastern China’s current ‘continental’ scale was slowly pieced coast; and Cantonese cuisine or yue cai to represent the together through more than 5,000 years of feudal culinary traditions of the south. -

The German Neo-Standard in a Europa Context

Peter Auer The German neo-standard in a Europa context Abstract (Deutsch) In verschiedenen europäischen Ländern ist in letzter Zeit die Frage diskutiert worden, ob sich zwischen der traditionellen Standardsprache und den regionalen bzw. Substandardva- rietäten ein neuer Standard („Neo-Standard“) herausgebildet hat, der sich nicht nur struk- turell vom alten unterscheidet, sondern sich auch durch ein anderes Prestige auszeichnet als dieser: er wirkt (im Vergleich) informeller, subjektiver, moderner, kreativer, etc. Im Bei- trag werden einige wesentliche Eigenschaften solcher Neo-Standards diskutiert und ihre Ent- wicklung als Folge der „Demotisierung“ (Mattheier 1997) der Standardsprache beschrieben. Abstract (English) Sociolinguists from various European countries have recently discussed the question of whether a new standard (“neo-standard“) has established itself between the traditional stand- ard variety of language on the one hand, and regional (dialects, regiolects, regional standards) and sub-standard varieties on the other. These new standards differ not only structurally but also in terms of their prestige: they appear to be informal, subjective, modern, creative, etc. while the traditional standards are based on an opposite set of values such as tradition, formality and closeness to the written word. In this contribution I discuss some key proper- ties of these neo-standards and identify them as one of the consequences of the “demotici- sation” (Mattheier 1997) of the standard variety. 1. Introduction In various European languages, recent decades have seen the establishment of ‘informal‘ standards which are distinct from the traditional standards in terms of structure and attitudes: the new standards are considered to be ‘more relaxed’, ‘more personal’, ‘more subjective’, ‘more creative’, ‘more modern’, etc. -

Social, Political and Cultural Challenges of the Brics Social, Political and Cultural Challenges of the Brics

SOCIAL, POLITICAL AND CULTURAL CHALLENGES OF THE BRICS SOCIAL, POLITICAL AND CULTURAL CHALLENGES OF THE BRICS Gustavo Lins Ribeiro Tom Dwyer Antonádia Borges Eduardo Viola (organizadores) SOCIAL, POLITICAL AND CULTURAL CHALLENGES OF THE BRICS Gustavo Lins Ribeiro Tom Dwyer Antonádia Borges Eduardo Viola (organizadores) Summary PRESENTATION Social, political and cultural challenges of the BRICS: a symposium, a debate, a book 9 Gustavo Lins Ribeiro PART ONE DEVELOPMENT AND PUBLIC POLICIES IN THE BRICSS Social sciences and the BRICS 19 Tom Dwyer Development, social justice and empowerment in contemporary India: a sociological perspective 33 K. L. Sharma India’s public policy: issues and challenges & BRICS 45 P. S. Vivek From the minority points of view: a dimension for China’s national strategy 109 Naran Bilik Liquid modernity, development trilemma and ignoledge governance: a case study of ecological crisis in SW China 121 Zhou Lei 6 • Social, political and cultural challenges of the BRICS The global position of South Africa as BRICS country 167 Freek Cronjé Development public policies, emerging contradictions and prospects in the post-apartheid South Africa 181 Sultan Khan PART TWO ContemporarY Transformations AND RE-ASSIGNMENT OF political AND cultural MEANING IN THE BRICS Political-economic changes and the production of new categories of understanding in the BRICS 207 Antonádia Borges South Africa: hopeful and fearful 217 Francis Nyamnjoh The modern politics of recognition in BRICS’ cultures and societies: a chinese case of superstition -

Serene Island Power Women Barton's Creek Interior

SERENE ISLAND POWER WOMEN BARTON’S CREEK INTERIOR INSPIRATION CAFÉ FLORAL SPRING/SUMMER 2019 RMshop.no “That first spring day lightens my mood” Franklin Park Wing Chair velvet, olive (NOK 1.4990), available in various colours velvet, linen and pellini, RM Beach Club Fillable Votive small (NOK 149)*, Seashell Fillable Votive (NOK 169), Summer Shell Fillable Votive (NOK 229), Best Of Summer Fillable Votive (NOK 149), RM Beach Club Fillable Votive medium (NOK 169)*. * Availble from April 2019. 5 “That first Hello Spring spring day I really hate the cold and although Christmas is my favourite time of This typical country trend has lasted for many years and has made our year, on 27 December I can again be longing for spring and the winter brand big and well-known, far beyond our national borders. And now we could not be over sooner. have given the collections a new touch without losing sight of our DNA. lightens The Netherlands is a real ice skating country. As soon as it freezes for We‘ve prepared our collection for the next step. The new RM should a week, the eleven-city virus re-emerges and everyone talks about the not only be there for the country-style fan, but also appeal to a broader race really happening again: the Elfstedentocht (Eleven Cities Tour). target group. As yet, that‘s worked really well, because we have grown my mood” The romance around the tour of tours in our beautiful Friesland is like mad again over the last years. wonderful, but I am Amsterdam born and when it freezes there is nothing more beautiful for me than the scene of skating people and A nice example of the new RM can be found in this spring magazine, their children on the canals after a few weeks of frost. -

Cultural Identities and National Borders

CULTURAL IDENTITIES AND NATIONAL BORDERS Edited by Mats Andrén Thomas Lindqvist Ingmar Söhrman Katharina Vajta 1 CULTURAL IDENTITIES AND NATIONAL BORDERS Proceedings from the CERGU conference held at the Faculty of Arts. Göteborg University 7-8 June 2007 Eds. Mats Andrén Thomas Linqvist Ingmar Söhrman Katharina Vajta 2 CONTENTS Contributers Opening Addresses Introduction 1. Where, when and what is a language? Ingmar Söhrman 2. Identity as a Cognitive Code: the Northern Irish Paradigm Ailbhe O’Corrain 3. Language and Identity in Modern Spain: Square Pegs in Round Holes? Miquel Strubell 4. Struggling over Luxembourgish Identity Fernand Fehlen 5. Language Landscapes and Static Geographies in the Baltic Sea Area Thomas Lundén 6. The Idea of Europa will be Fullfilled by Muslim Turkey Klas Grinell 7. National identity and the ethnographic museum The Musée du Quai Branly Project: a French answer to multiculturalism? Maud Guichard-Marneuor 8. Främlingsidentitet och mytbildning av den utländske författaren [English summary: Mythmaking of the Foreign Author and a Reflection on the Identity as a Stranger: The Case of the Swedish Author Stig Dagerman in France and Italy] Karin Dahl 9. Den glokale kommissarien: Kurt Wallander på film och TV [English summary: Kurt Wallander on film and TV] Daniel Brodén 10. Staden, staten och medborgarskapet [English summary: Studying “undocumented immigrants” in the city with Lefebvre’s spatial triad as a point of departure] Helena Holgersson 3 11. Digging for Legitimacy: Archeology, Identity and National Projects in Great Britain, Germany and Sweden Per Cornell, Ulf Borelius & Anders Ekelund 12. Recasting Swedish Historical Identity Erik Örjan Emilsson 4 Contributers Mats Andrén is professor in The History of Ideas and Science at Göteborg University from 2005. -

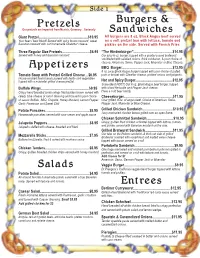

Zh New Menu PAGES 2 & 3 2-23-17

Our pretzels are imported from Munich, Germany…Seriously Giant Pretzel.....................................................$10.95 All burgers are 8 oz. Black Angus beef served Your beers’ best friend! Served with spicy brown mustard, sweet on a soft pretzel bun with lettuce, tomato and Bavarian mustard with our homemade Obatzda* cheese. pickles on the side. Served with French Fries. Three Regular Size Pretzels..............................$6.95 “The Hindenburger”..........................................$14.95 Served with honey and Bavarian mustard Our juicy 8 oz. burger, topped with a quarter pound bratwurst smothered with sautéed onions, thick cut bacon, & your choice of cheese. American, Swiss, Pepper Jack, Muenster or Blue Cheese. BBQ Burger.......................................................$13.95 8 oz. juciy Black Angus burger topped with your choice of pulled Tomato Soup with Pretzel Grilled Cheese ...$6.95 pork or brisket with Cheddar cheese, pickled onions and jalapeňo. House smoked fresh tomato pureed with herbs and vegetables topped with a muenster grilled cheese pretzel. Hot and Spicy Burger........................................$12.95 Some like it HOT!!! Our 8 oz. Black Angus beef burger, topped Buffalo Wings....................................................$9.95 with sliced Andouille and Pepper Jack cheese. Crispy hand breaded jumbo wings fried golden brown served with Have a cold beer handy. celery, blue cheese or ranch dressing and tossed in your choice Cheeseburger.....................................................$11.95 of sauce: Buffalo, BBQ, Chipotle, Honey Mustard, Lemon Pepper, Char grilled, 8 oz. of angus beef. Choice of American, Swiss, Garlic Parmesan and Sweet Chili Pepper Jack, Muenster or Blue Cheese. Potato Pancakes................................................$5.95 Grilled Chicken Sandwich.................................$10.95 Juicy marinated chicken breast grilled over an open flame. Homemade pancakes served with sour cream and apple sauce. -

The Children of San Souci, Dessalines/Toussaint, and Pétion

The Children of San Souci, Dessalines/Toussaint, and Pétion by Paul C. Mocombe [email protected] West Virginia State University The Mocombeian Foundation, Inc. Abstract This work, using a structurationist, structural Marxist understanding of consciousness constitution, i.e., phenomenological structuralism, explores the origins of the contemporary Haitian oppositional protest cry, “the children of Pétion v. the children of Dessalines.” Although viewed within racial terms in regards to the ideological position of Pétion representing the neoliberal views of the mulatto elites, and economic reform and social justice representing the ideological position of Dessalines as articulated by the African masses, this article suggests that the metaphors, contemporarily, have come to represent Marxist categories for class struggle on the island of Haiti within the capitalist world-system under American hegemony at the expense of the African majority, i.e., the Children of Sans Souci. Keywords: African-Americanization, Vodou Ethic and the Spirit of Communism, Religiosity, Black Diaspora, Dialectical, Anti-dialectical, Phenomenological Structuralism Introduction Since 1986 with the topple of the Haitian dictator, Jean-Claude “Baby-Doc” Duvalier (1951-2014), whose family ruled Haiti for almost thirty-years, the rallying cry of Haitian protest movements against dictatorship and American neoliberal policies on the island has been, “the children of Dessalines are fighting or stand against the children of Pétion.” The politically charged moniker is an allusion to the continuous struggles over control of the Haitian nation- state and its ideological apparatuses between the Africans who are deemed the descendants of Jean-Jacques Dessalines, the father of the Haitian nation-state; and the mulatto elites (and more recently the Syrian class) who are deemed heirs of the mulatto first President of the Haitian Republic, Alexandre Pétion. -

P18 Layout 1

THURSDAY, OCTOBER 9, 2014 SPORTS English Premier League explores global expansion LONDON: English clubs’ interest in playing dition of anonymity because the discussions have Arnold told the AP: “That’s still an area that’s under watch, who knows?” Pointing to the crowds at matches abroad has prompted the Premier been in private. Although playing a regular season some development. You’ve seen on the tour the some pre-season friendlies in the United States, League to explore the possibilities of expansion game abroad would appear unlikely in the immedi- engagement we get abroad.” Scudamore said: “You wouldn’t get more even if overseas. ate future, the league is looking into organizing Premier League games are broadcast into 650 there was three points, six points, or even nine The league was forced to scrap plans six years lucrative pre-season friendlies and expanding the million homes in 175 countries, according to points riding on that particular game.” ago to add an extra 39th round of matches at ven- existing Premier League Asia trophy tournament to league statistics. The league has been wary about While clubs like United and Liverpool can secure ues across the world amid opposition domestical- other continents. reviving plans to take a game abroad after the ini- lucrative deals for pre-season games, it would be ly and from FIFA. But league chief executive The international interest in preseason games tial discussion in 2008 angered both domestic fans clubs with smaller global fan bases that could ben- Richard Scudamore recently acknowledged that was highlighted by Manchester United’s friendly and FIFA, with questions also about upsetting the efit from the Premier League helping to organize clubs still back the idea. -

Around the World in 80 Food Trucks 1 Preview

Lobster mac ‘n’ cheese, BOB’s Lobster 26 Buttermilk-fried-chicken biscuit OCEANIA SOUTH AMERICA Newport bowl with tofu, Califarmication 144 Great balls of fire pork & beef meatballs, sandwiches, Humble Pie 56 Detox açai bowl, Açai Corner 82 Peruvian sacha taco, Hit ‘n Run 110 BEC sandwich, Paperboy 146 contents The Bowler 28 Super cheddar burger, Paneer 58 Carolina smoked pulled pork sandwich, The Cajacha burger, Lima Sabrosa 112 The Viet banh mi, Chicago Lunchbox 148 Goat’s cheese, honey & walnut Turkey burger, Street Chefs 60 Sneaky Pickle 84 Yakisoba bowl, Luca China 114 Blue cheese slaw, Banjo's 150 Introduction 5 toasted sandwich, The Cheese Truck 30 Forest pancake, Belki&Uglevody 62 The Bahh lamb souvlaki, Argentine sandwich, El Vagabundo 116 Old-fashioned peach cake, The Peach Truck 152 Jerusalem spiced chicken, Laffa 32 Greek Street Food 86 Uruguayan flan, Merce Daglio Sweet Truck 118 Alabama tailgaters, Fidel Gastro’s 154 EUROPE Fried chicken, Mother Clucker 34 AFRICA & MIDDLE EAST Mr Chicken burger, Mr Burger 88 Tapioca pancake, Tapí Tapioca 120 Nanner s’more, Meggrolls 156 Spicy Killary lamb samosas, Chicken, chilli & miso gyoza, Rainbo 36 South African mqa, 4Roomed eKasi Culture 64 Tuscan beef ragu, Pasta Face 90 Red velvet cookies, Misunderstood Heron 6 Asparagus, ewe’s cheese, mozzarella & Asian bacon burger, Die Wors Rol 66 The Fonz toastie, Toasta 92 NORTH AMERICA Captain Cookie and the Milk Man 158 San Francisco langoustine roll, hazelnut pizza, Well Kneaded 38 Chicken tikka, Hangry Chef 68 Butter paneer masala, Yo India