Stories from Design and Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tarrington Tatler

Tarrington Tatler Measuring up the churchyard Churchyard to get a facelift. Pg 10 Village Quiz. Pg 6 Heartfelt thanks. Pg 14 Will you join the club? Pg 17 Didn’t you do well! Pg 23 Deadline for submission for the next issue: Sunday 21st May Hello fellow Tarringtonians, I hope you are enjoying all the spring bulbs - the churchyard has excelled as it always does, and everything in the garden is bursting into growth. There are plenty of garden related activities to take note of, including new plans for the churchyard… The BBC is coming to Hereford Cathedral for Songs of Praise and there are some great Easter services and activities in our own Hop Churches. I always welcome contributions from anyone in the Parish, but please have the courage to put your name to it. I won’t publish anything that is anonymous. I hope you enjoy Easter and the two May bank holidays coming up. Have lots of Hot Cross Buns, but don’t eat too many Easter eggs! Judi Did You Know? It has been suggested by some people - David Lack for one in his excellent book “Robin Redbreast” in 1950 - that although the sexes are very sim- ilar, the brown fore- head is “U” shaped in male robins and “V” shaped in females. Blowed if I can tell! 2 Dates for your diary & Forthcoming Attractions Further Date Event Info 30 March Propagation Talk. Radway Bridge Garden Centre Pg 15 7 April Village Quiz Pg 6 10 Apil WI Cookery demonstration. Contact Margaret Townsend 890221 16 April Hereford Cathedral’s Easter Day Eucharist live on BBC1 Pg 25 17 April Songs of Praise at Hereford Cathedral Pg 25 19 April Leed’s Clothworkers Consort Choir. -

Teachers' Guide

Teachers’ Guide FOREWORD Try out these riddles and see if you can answer them. 1. A woman shoots her husband. Then she holds him under water for over five minutes. Finally, she hangs him. Five minutes later, they both go out for a meal together. How can this be? 2. Children aged between 4 and 6 can solve this problem in 5 minutes. 95% of adults can’t. Can you? 8898=7 4566=2 1203=1 2313=0 4566=2 7774=0 1003=2 4500=? The answers to both riddles are at the back of this book on page 314. I must confess. I didn’t get either of them. Was it because I think in a certain way without seeing other possibilities? Is it because I don’t spend enough time problem solving with riddles and brain teasers? It could well be. I would feel confident after seeing the answers that I would not be caught out with these types of riddles again. The question is; do the students in our care deserve the same platform of thinking? They have been born on the cusp of a century that has seen three technological leaps. These are: 1. Long distance communication: a faster postal service, the telephone and the mobile phone. 2. Transport: the car, the engine-powered ship and the airplane. 3. The storing of knowledge on computers; the modern phones are more powerful than the best computer available to George Bush Sr. They are going to have to work in a century which will see nine or more. -

Airwaves (1984-02 And

AIRWAVES A S.rvlc• of Continuing Education & Ext8nslon Unlv.rslty of Minnesota Duluth VolulM 5 NumlMr 1 F.bruary-March .1984 Eddie Williams stars in Northland Hoedown Concert, · Tuesday, March 27, 8 p.m., Orpheum Cafe kumd 103.3 fm Station Manager • Tom Livingston Program Director • John Ziegler Public Affairs Directot • Paul Schmitz Producer/ Outreach • Jean Johnson Engineer • Kirk Kersten Re orf to the Listener Volunteer Staff Bill Agnew, Kath Anderson, Mark Anderson, Bob Andresen, Leo Babeu, By Tom Livingston, Station Manager Chris Baker, Kent Barnard, Jim Boeder, Dave Brygger, Jan Cohen, Christopher WXPR Qualitied for Funding by CPB able to add two more channels, when we their impressions of the event at press Devaney, Bruce Eckland, Pat Eller, Phil installed our own dish. This increased time. Enke, Doug Fifield, Susanna Frenkel, Congratulations to Pete Nordgren and the number of programs available to us (rewritten from "Don Ness Blows His . Matt Fust, Bev Garberg, Stan Goltz, the crew at the WXPR for their (Jazz Alive and NPR Playhouse), but Cool," a chapter of the upcoming Doug Greenwood, Jim Gruba, Bill qualification by CPB. Nordgren, a still left us unable to use channels which blockbuster "The Memories of Don Hansen, Paul Hanson, Gordon Harris, former student at UWS and stat.ion carry independent product.ions, which Ness" on Ness records and tapes) Dean Hauge, Gerry Henkel, Lew manager of KBSB in Bemidji, has been have included live jazz, blues, bluegrass Hudson, Tim Jenkins, Dave Johnson, working for some three years to establish and folk music concerts, ·radio dramas, Comings and Goings Bob King, Andy Livingston, Dean the station, which went on the air last and public affairs programs. -

Country Goes Cable California Retailers Weather Storms New Trends in Store Fixtures Salute to Meltillis

NEWSPAPER $3.00 BOOSTING SALES WITH GRAMMY AWARDS COUNTRY GOES CABLE CALIFORNIA RETAILERS WEATHER STORMS NEW TRENDS IN STORE FIXTURES SALUTE TO MELTILLIS \ s I I Mel Tlllls A ZSifi ^nniud Convention April 10-14, 1983 Fontainebleau Hilton Hotel Miami Beach, Florida 9. 10. THE CONVENTION CROSSWORD PUZZLE ACROSS 1. The trade association for marketing music Industry unveiled at NARM "Spotlight" speakers 13. Luncheon honoring NARM officers 14. NARM Markets 1 7. Performers at luncheons and dinners 19. Exhibit area highlights 20. Inform via broadcast and print media 23. Host of spectacular luncheon show 24. Merchandiser of the Year Award 25. More about this promotion alternative 26. Super industry marketing campaign 27. Convention climax 29. Outstanding new opportunity 30. Mid-day Convention showtime 32. What happens at NARM 33. Convention meeting place " 34. In Ireland, "Gift 28. DOWN31. 2. NARM Music 3. Convention eye-openers 4. New participants 5. What NARM members do best 6. Honored at NARM Awards Banquet 7. NARM's newest market expansion program 8. Special interest Convention schedule 11. Tennis, golf and running on Miami Beach 12. Product line getting first-time Convention program 15. Key to retailer's success 16. Relax here after Convention business day 18. Awarded at Foundation Dinner 21. Hot topic of Convention program 22. "Class" topic fora Convention program Profound packaging opportunity Software and games NARM MARKETS MUSIC” CONVENTION THEME "NARM Markets Music" encompasses in a short but dising of specialty product (children's and classical). An very meaningful phrase, the focus of the program for exciting new dimension is added to the Convention the 1983 NARM Convention. -

Com ,S Oftate

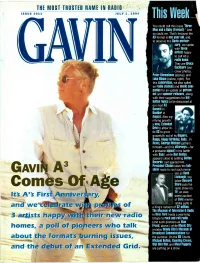

THE MOST TRUSTED NAME IN RADIO ISSUE 2011 JULY 1, 1994 This Week You could call this issue 'Three Men and a Baby (Format)." And so could we. That's because the A3 format is one year old, and, to observe this Gavin anniver- sary, we spoke with three artists happy to call A3 a radio home. They are Bruce Cockburn (our cover photo), Peter Himmelman (above), and Luka Bloom (below, right). For this celebration, we also called on radio stations and music com- panies for an update on person- nel and summer releases, along with their suggestions for hot - button topics to be discussed at our next A3 Summit in Boulder in August. Also sig- nifying growth: a new, Extended Grid to allow lit- tle A3 to grow gracefully out of its diapers. Happy, happy birthday, baby...In News, George Michael gathers himself-and his attorneys-for a probable appeal in his battle with Sony, while Don Henley appears close to settling Geffen Records' suit against him. President Clinton takes the talk - show route to rout such neme- GAVI A3 ses as Rush Limbaugh; top talker Howard ,s Stern puts his Com OftAte radio show on TV; an awe- It's A3'sFirsiAnniverAary, some auction of Elvis memo- rabilia pulls in and we a King's ransom of S2 million. The Museum of Television & Radio in New York hosts a year -long 3 artists hap tribute to rock and roll radio (and such pioneers as Alan homes, a pI of plo eers who talk Freed, above ) while Music City invades Windy City's Museum of Broadcast Communications for about the foat's4wItaing issues, the summer. -

Downbeat.Com January 2016 U.K. £3.50

JANUARY 2016 U.K. £3.50 DOWNBEAT.COM DOWNBEAT LIZZ WRIGHT • CHARLES LLOYD • KIRK KNUFFKE • BEST ALBUMS OF 2015 • JAZZ SCHOOL JANUARY 2016 january 2016 VOLUME 83 / NUMBER 1 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer ŽanetaÎuntová Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens Editorial Assistant Baxter Barrowcliff ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sam Horn 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: -

Jay Newland Discography

JDManagement.com 914.777.7677 Jay Newland - Discography updated 09.01.13 P=Produce / ED=Edit / M=Mix / E=Engineer / MA=Mastering / RM=Remastering / SM=Surround Mix GRAMMYS (8) MOVIE STUDIO / RECORD LABEL / ARTIST / COMPOSER / PROGRAM FILM SCORE / ALBUM / TV SHOW CREDIT NETWORK Charlie Haden Land Of The Sun E/M Verve Best Latin Jazz Album Charlie Haden Nocture E/M Verve Best Latin Jazz Album Michael Brecker Quindectet Wide Angles E/M Verve Best Large Jazz Ensemble Album Norah Jones "Don't Know Why" P/E/M Blue Note Record of the Year Norah Jones Come Away With Me P/E/M Blue Note Album of the Year Norah Jones Come Away With Me P/E/M Blue Note Best Pop Vocal Album Norah Jones Come Away With Me P/E/M Blue Note Best Engineered Album, Non-Classical Herbie Hancock, Michael Brecker & Roy Hargrove Directions In Music: Live At Massey Hall E/M Verve Best Jazz Instrumental Album, Indiv. Or Group ARTIST SINGLE/ALBUM CREDIT LABEL 2013 Ayo 2013 release P/E/M Mercury Ayo "Fire" single feat. Youssoupha P/E/M Mercury Gregory Porter Liquid Spirit E/M Blue Note Jane Monheit The Heart of the Matter M Emarcy/Decca/Universal Records Juliette Greco Jacques Brel Tribute M Universal France Randy Weston Project 2013 release E/M Universal France Christian Escoude Saint Germain Des Pres The Music of John Lewis E/M Universal France Terez Montcalm 2013 release P/E/M Universal France The Dixie Hummingbirds Music In the Air: All Star Tribute E Entertainment One 2012 Melody Gardot The Absence E Decca/Verve Etta James The Complete Private Music Blues, Rock 'n' Soul Albums Collection E/M Sony Charlie Haden/Hank Jones. -

100 Kiued by Tornadoes

IIIani^rBtnr Evraftts $mO> BATURDAT, APRIL' 4.188*. AVraAOE DAILY dBCITLATIOM THE WBATHEB for the Month of Maroh, 1986 Forecast of U. S. Weatbei BarsMi. Flowers and Plants Hartford for all oocaaiona. EYES EXAMINED A FREE Delivered anywhere I WATKINS BROS., - 5 , 8 4 8 Bain this afternoon and possibly The private duty nurwe of Man Sale of Food and FILMS INCURPOBATBO BCeaber a< the Aodit c h e s te r wlin meet a t the clinic DEVEMtPEU ANU eau-ly tonight; colder tonight; Tues Small Weekly Payments. BorcM of Otroolatiana. day fair and colder. \M lding on Haynes street Monday PKIATED ENLARGEMENT ROBERT K. ANDERSON “emoon' ht 6 o'clock. Ail are re- Hot Cross Buns^ 24-HOUH SERVICE WITH EVERY ROLL OF FILM Foneral Director MANCHESTER — A (ITY OF VILLAGE (HARM ^^tteated to attend. Prescriptions Filled. > Classes Repaired. DEVELOPED AND PRINTED Thursday, April 9, 2 :30 P. M. VOL. LV„ NO. 160. (ClaaalBed Adverttslng on Pago 10.) Film Deposit Box At Ail work done on premises. Wm. 3. Bergeron, Optometrist Funeral service in home MANCHESTER, CONN., MONDAY, APRIL 6, 1936. (TWELVE PACES) PRICE THREE CENtS ■ Hale’s Store Basement We do irmeral machine and *> Store Entrance. 40e like surroundings. ttperimeniai work, also make Group 9, Center Church Women. apeclal machines. Jigs, tools. RICHARD STONE, Optician TM£ TLOR/ST 142 EAST CENTER ST. Delirious Home Made Buns with 17 Oak Street Fruit, 25c a do*. Order by Mon Elite Studio Telephone: Fred H. Norton day night Dial S57S or 6905. KEMP'S 739 Main St., State Theater Building, Tel. -

Beck Reverend Horton Heat Mc 900 Ft

GPO BECK One Foot In The Grave •K REVEREND HORTON HEAT Liquor In The Front • Sub Pop-lnterscope MC 900 FT JESUS One Step Ahead Of The Spider •american FIFTH COLUMN 36C •K VMJ! SOUNDGARDEN SURE THING! aRnivu CX LIGPT RIDE SPONTANEOUS COMBUSTION Your shirt will stink for weeks Recorded Live At CBGB 12-19-1993 Glamorous • Deaf As A Bat • Sea Sick • Bloody Mary • Mistletoe • Nub Elegy • Killer McHann • Dancing Naked Ladies • Fly On The Wall Boilermaker • Puss • Gladiator • Wheelchair Epidemic • Monkey Trick Fifteen tracks of teeth-loosening madness. CD. Cassette. Limited Edition Vinyl. gtdllt pace 3... Johnn Rebel Redeemed ash First of all, what everyone wants to know about a long-dis- tance interview with Johnny Cash: No, he didn't answer the phone and say "Hello—I'm Johnny Cash." Still, it is a little disconcerting at first, hearing that low ominous voice over the telephone, speaking from his Tennessee cabin, discussing the weather or reading off the address for his House Of Cash management office. "This is on album I've always wanted to do," he says of American Recordings. "I even had a name 25 years ago for this album, it was going to be called Johnny Cash Alone. Years later Ithought about it again and wanted to do an album like this, and call it Johnny Cash Up Close. But this same concept has been in my mind since the early '70s." About his first meeting with producer/label head Rick Rubin, Cash recalls, "I liked the way he talked. Because right off he said, 'I'm familiar with most of your work, and you know what you do best. -

Horace Tapscott Papers PASC-M.0237

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt187019m6 No online items Finding Aid for the Horace Tapscott Papers PASC-M.0237 Finding aid prepared by UCLA Library Special Collections staff UCLA Library Special Collections Online finding aid last updated 2021 January 21. Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 [email protected] URL: https://www.library.ucla.edu/special-collections Finding Aid for the Horace PASC-M.0237 1 Tapscott Papers PASC-M.0237 Contributing Institution: UCLA Library Special Collections Title: Horace Tapscott papers Creator: Tapscott, Horace Identifier/Call Number: PASC-M.0237 Physical Description: 37.5 Linear Feet(75 boxes) Date (inclusive): 1960-2002 Abstract: The collection consists of sound recordings, musical compositions and arrangements of Horace Tapscott and other composers, and the performances of the Pan Afrikan Peoples Arkestra and the Union of God's Musicians and Artists Ascension. The collection is in the midst of being processed, and updates will be made to this finding aid periodically. Stored off-site. All requests to access special collections material must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Language of Material: Materials are in English. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. All requests to access special collections materials must be made in advance using the request button located on this page. Physical Characteristics and Technical Requirements CONTAINS AUDIOVISUAL MATERIALS: This collection contains both processed and unprocessed audiovisual materials. For information about the access status of the material that you are looking for, refer to the Physical Characteristics and Technical Requirements note at the series and file levels. -

Title Format Released (Jerry Bergonzi/Bobby Watson/Victor Lewis) Together Again for the First Time CD 1997 ???? ????? CD 1990 4

Title Format Released (Jerry Bergonzi/Bobby Watson/Victor Lewis) Together Again For The First Time CD 1997 ???? ????? CD 1990 4 Giants Of Swing 4 Giants Of Swing CD 1977 Abate, Greg It'S Christmastime CD 1995 Monsters In The Night CD 2005 Evolution CD 2002 Straight Ahead CD 2006 Bop City: Live At Birdland CD 2006 Abate, Greg Quintet Horace Is Here CD 2004 Bop Lives CD 1996 Adams, George & Don Pullen Don't Lose Control CD 1979 Adams, Greg Midnight Morning CD 2002 Adams, Pepper 10 to 4 at the 5-Spot CD 1958 Adderley, Cannonball The Poll Winners: Volume 4 CD 1960 The Cannonball Adderley Quintet In San Francisco [Live] [Bonus Track] CD 1959 Adderley, Cannonball With Bill Evans Know What I Mean? CD 1961 Adderley, Nat Work Song CD 1990 Ade & His African Beats, King Sunny Juju Music CD 1982 Aggregation, The Groove’s Mood CD 2008 Akiyoshi, Toshiko Desert Lady/Fantasy CD 1993 Live at Maybeck Recital Hall: Volume 36 CD 1994 Finesse CD 1978 Alaadeen and the deans of swing Aladeen And The Deans Of Swing Plays Blues For RC And Josephine, Too CD 1995 Alaadeen, Ahmad New Africa Suite CD 2005 Time Through The Ages CD 1987 Page 1 of 79 Title Format Released Albany, Joe The Right Combination CD 1957 Alden, Howard & Jack Lesberg No Amps Allowed CD 1988 Alexander, Eric Solid CD 1998 Alexander, Monty Goin' Yard CD 2001 Jamboree CD 1998 Ray Brown Trio - Ray Brown Monty Alexander Russell Malone (Disc 2-2) CD 2002 Reunion in Europe CD 1984 Ray Brown Monty Alexander Russell Malone (Disc 1) CD 2002 My America CD 2002 Monty Meets Sly And Robbie CD 2000 Stir It -

Little Seal-Skin

Little Seal−skin Eliza Keary Little Seal−skin Table of Contents Little Seal−skin..........................................................................................................................................................1 Eliza Keary.....................................................................................................................................................2 LITTLE SEAL−SKIN....................................................................................................................................4 THE LEGEND OF THORA..........................................................................................................................9 SUNBEAMS IN THE SEA.........................................................................................................................11 THE GOOSE−GIRL....................................................................................................................................12 ASDISA.......................................................................................................................................................15 THE MILL STREAM..................................................................................................................................18 * * * * *........................................................................................................................................................20 DISENCHANTED.......................................................................................................................................21