Initiative on Soaring Food Prices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feasibility Study of Kailash Sacred Landscape

Kailash Sacred Landscape Conservation Initiative Feasability Assessment Report - Nepal Central Department of Botany Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, Nepal June 2010 Contributors, Advisors, Consultants Core group contributors • Chaudhary, Ram P., Professor, Central Department of Botany, Tribhuvan University; National Coordinator, KSLCI-Nepal • Shrestha, Krishna K., Head, Central Department of Botany • Jha, Pramod K., Professor, Central Department of Botany • Bhatta, Kuber P., Consultant, Kailash Sacred Landscape Project, Nepal Contributors • Acharya, M., Department of Forest, Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation (MFSC) • Bajracharya, B., International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) • Basnet, G., Independent Consultant, Environmental Anthropologist • Basnet, T., Tribhuvan University • Belbase, N., Legal expert • Bhatta, S., Department of National Park and Wildlife Conservation • Bhusal, Y. R. Secretary, Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Das, A. N., Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Ghimire, S. K., Tribhuvan University • Joshi, S. P., Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Khanal, S., Independent Contributor • Maharjan, R., Department of Forest • Paudel, K. C., Department of Plant Resources • Rajbhandari, K.R., Expert, Plant Biodiversity • Rimal, S., Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation • Sah, R.N., Department of Forest • Sharma, K., Department of Hydrology • Shrestha, S. M., Department of Forest • Siwakoti, M., Tribhuvan University • Upadhyaya, M.P., National Agricultural Research Council -

Forests and Watershed Profile of Local Level (744) Structure of Nepal

Forests and Watershed Profile of Local Level (744) Structure of Nepal Volumes: Volume I : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 1 Volume II : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 2 Volume III : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 3 Volume IV : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 4 Volume V : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 5 Volume VI : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 6 Volume VII : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 7 Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Department of Forest Research and Survey Kathmandu July 2017 © Department of Forest Research and Survey, 2017 Any reproduction of this publication in full or in part should mention the title and credit DFRS. Citation: DFRS, 2017. Forests and Watershed Profile of Local Level (744) Structure of Nepal. Department of Forest Research and Survey (DFRS). Kathmandu, Nepal Prepared by: Coordinator : Dr. Deepak Kumar Kharal, DG, DFRS Member : Dr. Prem Poudel, Under-secretary, DSCWM Member : Rabindra Maharjan, Under-secretary, DoF Member : Shiva Khanal, Under-secretary, DFRS Member : Raj Kumar Rimal, AFO, DoF Member Secretary : Amul Kumar Acharya, ARO, DFRS Published by: Department of Forest Research and Survey P. O. Box 3339, Babarmahal Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: 977-1-4233510 Fax: 977-1-4220159 Email: [email protected] Web: www.dfrs.gov.np Cover map: Front cover: Map of Forest Cover of Nepal FOREWORD Forest of Nepal has been a long standing key natural resource supporting nation's economy in many ways. Forests resources have significant contribution to ecosystem balance and livelihood of large portion of population in Nepal. Sustainable management of forest resources is essential to support overall development goals. -

Cultural Beliefs and Traditional Rituals About Child Birth Practice in Rural, Nepal

MOJ Public Health Cultural Beliefs and Traditional Rituals about Child Birth Practice in Rural, Nepal Abstract Research Article Background: Volume 5 Issue 1 - 2016 About 98% of newborn deaths occur in developing countries, where most newborns deaths occur at home [1]. In Nepal, approximately, 90% Action Works Nepal, Kathmandu, Nepal of deliveries take place at home [2]. Information about reasons for delivering at home and newborn care practices in rural areas of Nepal is lacking and such *Corresponding author: Sanjaya Bahadur Chand, Health informationObjectives: will be useful for policy makers. Tel: +977 9851202315; Email: The objective of this study is to explore and analyze the cultural Project Officer, Action Works Nepal, Kathmandu, Nepal, beliefsMethods: and traditional rituals about child birth practice in rural, Nepal. A cross-sectional survey was carried out in the Kesharpur primary Received: June 06, 2016 | Published: health care centre of Baitadi district, Far western Nepal during April - May, 2013. November 04, 2016 Self administered questionnaire to the reproductive age (15-49) year’s women whoResults: experienced home delivery during the last year and new pregnant. A total of 100 mothers were interviewed. 13% were deliveries at health institute and 87% were at home deliveries. Only 20% of deliveries had a skilled birth attendant present and 80% mothers gave birth from others support and alone. Only 1% women were live in hospital during postpartum period, 60% lived in home and 39% in cow shed. Only 45% had used a clean home delivery kit and only 66% were use boiled string or threat for cord tie. Maximum women were practice wood for cord cut surface 43%. -

THE GEOGRAPHICAL JOURNAL of NEPAL Volume 8 -9 December 2010-2011 the GEOGRAPHICAL JOURNAL of NEPAL JOURNAL of NEPAL in This Issue

Volume 8-9 December 2010-2011 Volume 8-9 December 2010-2011 THE GEOGRAPHICAL JOURNAL OF NEPAL THE GEOGRAPHICAL THE GEOGRAPHICAL JOURNAL OF NEPAL JOURNAL OF NEPAL In this issue: Seismic Vulnerability Assessment of Buildings in GIS Environment: Dhankuta Municipality, Nepal Basanta Paudel and Pushkar K Pradhan Socio-Economic Status of Dalits of the Western Tarai Villages, Nepal Bhoj Raj Kareriya School Dropout and its Relationship with Quality of Primary Education in Nepal Binay Kumar Kushiyait Community Forests Ensuring Local Governance and Livelihood: A Case Study in Sunwal VDC, A Journal Nawalparasi, Nepal Devi Prasad Paudel on Management and Economics Landholding Size and Educational and Occupational Status in Two Villages of Dang Volume 8 -9 December 2010-2011 8 -9 December Volume Dharani Kumar Sharma Role of Irrigation in Crop Production and Productivity: A Comparative Study of Tube Well and Canal Irrigation in Shreepur VDC of Kanchanpur District Narayan Prasad Paudyal Biodiversity and Livelihood of Pangre Jhalas Wetland, Morang District, Nepal Puspa Lal Pokhrel Persistent Change in Livelihoods in Bhirgaun, Eastern Nepal Shambhu P Khatiwada Hardships in Mountain Livelihood: Findings from Yari Village, Humla District Shiba Prasad Rijal The Activities Undertaken by the Central Department of Geography, Tribhuvan University: 2008-2011 Pushkar K Pradhan Central Department of Geography Central Department of Geography Tribhuvan University, Kirtipur, Kathmandu, Nepal Faculty ofSHANKER Humanities DEV and CAMPUS Social Sciences Tel: 977-01-4330329, Fax: 977-1-4331319 Tribhuvan UniversityUniversity E-mail: [email protected] Kirtipur,Ramshah Kathmandu, Path, Kathmandu Nepal The Geographical Journal of Nepal The Geographical Journal of Nepal is a regular publication of the Central Department of Geography, Tribhuvan University. -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

Pray for Nepal

Pray for Nepal Bajhang Bajura Doti Achham Kailali Seti, Bajhang Greetings in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, Thank-You for committing to join with us to pray for the well-being of every village in our wonderful country. Jesus modeled his love for every village when he was going from one city and village to another with his disciples. Next, Jesus would mentor his disciples to do the same by sending them out to all the villages. Later, he would monitor the work of the disciples and the 70 as they were sent out two-by-two to all the villages. (Luke 8-10) But, how can we pray for the 3,984 VDCs in our Country? In the time of Nehemiah, his brother brought him news that the walls of Jerusalem were torn down. The wall represented protection, safety, blessing, and a future. Nehemiah prayed, fasted, and repented for the sins of the people. God answered Nehemiah’s prayers. The huge task to re-build the walls became possible through God’s blessings, each person building in front of their own houses, and the builders continuing even in the face of great persecution. For us, each village is like a brick in the wall. Let us pray for every village so that there are no holes in the wall. Each person praying for the villages in their respective areas would ensure a systematic approach so that all the villages of the state would be covered in prayer. Some have asked, “How do you eat an Elephant?” (How do you work on a giant project?) Others have answered, “One bite at a time.” (One step at a time - in small pieces). -

Field Bulletin

Issue No.: 01; April 2011 United Nations Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator’s Office FIELD BULLETIN Chaupadi In The Far-West Background Chaupadi is a long held and widespread practice in the Far and Mid Western Regions of Nepal among all castes and groups of Hindus. According to the practice, women are considered ‘impure’ during their menstruation cycle, and are subsequently separated from others in many spheres of normal, daily life. The system is also known as ‘chhue’ or ‘bahirhunu’ in Dadeldhura, Baitadi and Darchula, as ‘chaupadi’ in Achham, and as ‘chaukulla’ or ‘chaukudi’ in Bajhang district. Participants of training on Chaupadi-WCDO Doti Discrimination Against Women During Menstruation According to the Accham Women’s Development Officer (WDO), more Women face various discriminatory practices in the context of than 95% of women are practicing chaupadi. The tradition is that women cannot enter inside houses, chaupadi in the district. Women kitchens and temples. They also can’t touch other persons, cattle, and Child Development Offices in green vegetables and plants, or fruits. Similarly, women practicing Doti and Achham are chaupadi cannot milk buffalos or cows, and are not allowed to drink implementing an ‘Awareness milk or eat milk products. Programme against Chaupadi’. The programme is supported by Save Generally, women stay in a separate hut or cattle shed for 5 days the Children and covers 19 VDCs in during menstruation. However, those experiencing menstruation for Achham and 10 VDCs in Doti.In the the first time should, according to practice, remain in such a shed for VDCs targeted by this program, the at least 14 days. -

Nepal National Association of Rural Municipality Association of District Coordination (Muan) in Nepal (NARMIN) Committees of Nepal (ADCCN)

Study Organized by Municipality Association of Nepal National Association of Rural Municipality Association of District Coordination (MuAN) in Nepal (NARMIN) Committees of Nepal (ADCCN) Supported by Sweden European Sverige Union "This document has been financed by the Swedish "This publication was produced with the financial support of International Development Cooperation Agency, Sida. Sida the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of does not necessarily share the views expressed in this MuAN, NARMIN, ADCCN and UCLG and do not necessarily material. Responsibility for its content rests entirely with the reflect the views of the European Union'; author." Publication Date June 2020 Study Organized by Municipality Association of Nepal (MuAN) National Association of Rural Municipality in Nepal (NARMIN) Association of District Coordination Committees of Nepal (ADCCN) Supported by Sweden Sverige European Union Expert Services Dr. Dileep K. Adhikary Editing service for the publication was contributed by; Mr Kalanidhi Devkota, Executive Director, MuAN Mr Bimal Pokheral, Executive Director, NARMIN Mr Krishna Chandra Neupane, Executive Secretary General, ADCCN Layout Designed and Supported by Edgardo Bilsky, UCLG world Dinesh Shrestha, IT Officer, ADCCN Table of Contents Acronyms ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Forewords ..................................................................................................................................... -

ZSL National Red List of Nepal's Birds Volume 5

The Status of Nepal's Birds: The National Red List Series Volume 5 Published by: The Zoological Society of London, Regent’s Park, London, NW1 4RY, UK Copyright: ©Zoological Society of London and Contributors 2016. All Rights reserved. The use and reproduction of any part of this publication is welcomed for non-commercial purposes only, provided that the source is acknowledged. ISBN: 978-0-900881-75-6 Citation: Inskipp C., Baral H. S., Phuyal S., Bhatt T. R., Khatiwada M., Inskipp, T, Khatiwada A., Gurung S., Singh P. B., Murray L., Poudyal L. and Amin R. (2016) The status of Nepal's Birds: The national red list series. Zoological Society of London, UK. Keywords: Nepal, biodiversity, threatened species, conservation, birds, Red List. Front Cover Back Cover Otus bakkamoena Aceros nipalensis A pair of Collared Scops Owls; owls are A pair of Rufous-necked Hornbills; species highly threatened especially by persecution Hodgson first described for science Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson and sadly now extinct in Nepal. Raj Man Singh / Brian Hodgson The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of participating organizations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of any participating organizations. Notes on front and back cover design: The watercolours reproduced on the covers and within this book are taken from the notebooks of Brian Houghton Hodgson (1800-1894). -

35173-013: Third Small Towns Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Project

Initial Environmental Examination Project Number: 35173-013 Loan Numbers: 3157 and 8304, Grant Number:0405 July 2020 Nepal: Third Small Towns Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Project - Enhancement Towns Project Prepared by the Government of Nepal for the Asian Development Bank This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Updated Initial Environmental Examination July 2020 NEP: Third Small Towns Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Project – Phidim, Khandbari, Duhabi, Belbari, Birtamod DasarathChanda, Mahendranagar, Adarshnagar-Bhasi, Tikapur, Sittalpati, Bijuwar and Waling Enhancement Town Projects Prepared by Small Towns Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Project, Department of Water Supply and Sewerage Management, Ministry of Water Supply, Government of Nepal for the Asian Development Bank. Updated Initial Environmental Examination (IEE) of 12 Enhancement Small Town Projects Government of Nepal Ministry of Water Supply Asian Development Bank Updated Initial Environmental Examination (IEE) Of Phidim, Khandbari, Duhabi, Belbari, Birtamod, DasarathChanda, Mahendranagar, Adarshnagar-Bhasi, Tikapur, Sittalpati, Bijuwar, and Waling Enhancement Town Projects Submitted in July 2020 PROJECT MANAGEMENT OFFICE (PMO) Third Small Town Water Supply and Sanitation Sector Project Department of Water Supply and Sewerage Management Ministry of Water Supply Updated Initial Environmental Examination (IEE) of 12 Enhancement Small Town Projects Table of Contents ABBREVIATIONS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. -

A Poverty Analysis in Baitadi District, Rural Far Western Hills of Nepal: an Inequality Decomposition Analysis

Munich Personal RePEc Archive A Poverty Analysis in Baitadi District, Rural Far Western Hills of Nepal: An Inequality Decomposition Analysis Maharjan, Keshav Lall and Joshi, Niraj Prakash Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation, Hiroshima University July 2007 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/35384/ MPRA Paper No. 35384, posted 13 Dec 2011 16:17 UTC A Poverty Analysis in Baitadi District, Rural Far Western Hills of Nepal: An Inequality Decomposition Analysis Keshav L. MAHARJAN Professor, Graduate School of International Development and Cooperation Hiroshima University, Hiroshima, Japan 739-8529 [email protected] Niraj P. JOSHI Graduate Student, Graduate School of International Development and Cooperation Hiroshima University, Hiroshima, Japan 739-8529 [email protected] Abstract Occupational caste is deprived in terms of education, and landholding. Due to this laboring and agriculture (specially small animals like goats and poultry) remain the prominent source of income for them. Average income from salaried job is the highest followed by remittance and that from laboring is the lowest. This led to the high concentration of Occupational caste under third and fourth income quartile (poorer). A share of income from agriculture in total income is the highest and the share from laboring is the lowest. Relative concentration coefficient (RCC-ci or gi) shows salaried job has both the highest income disequalizing effect (ci = 1.56 or gi = 1.49) as well as the highest factor inequality weight (wici) followed by agriculture. In case of Melauli, however, salaried job followed by remittance has the highest income disequalizing effect. Negative values of Relative Concentration Coefficient and factor inequality weight for laboring indicate that income from it has the income equalizing effect. -

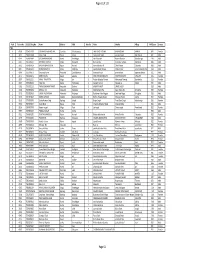

TSLC PMT Result

Page 62 of 132 Rank Token No SLC/SEE Reg No Name District Palika WardNo Father Mother Village PMTScore Gender TSLC 1 42060 7574O15075 SOBHA BOHARA BOHARA Darchula Rithachaupata 3 HARI SINGH BOHARA BIMA BOHARA AMKUR 890.1 Female 2 39231 7569013048 Sanju Singh Bajura Gotree 9 Gyanendra Singh Jansara Singh Manikanda 902.7 Male 3 40574 7559004049 LOGAJAN BHANDARI Humla ShreeNagar 1 Hari Bhandari Amani Bhandari Bhandari gau 907 Male 4 40374 6560016016 DHANRAJ TAMATA Mugu Dhainakot 8 Bali Tamata Puni kala Tamata Dalitbada 908.2 Male 5 36515 7569004014 BHUVAN BAHADUR BK Bajura Martadi 3 Karna bahadur bk Dhauli lawar Chaurata 908.5 Male 6 43877 6960005019 NANDA SINGH B K Mugu Kotdanda 9 Jaya bahadur tiruwa Muga tiruwa Luee kotdanda mugu 910.4 Male 7 40945 7535076072 Saroj raut kurmi Rautahat GarudaBairiya 7 biswanath raut pramila devi pipariya dostiya 911.3 Male 8 42712 7569023079 NISHA BUDHa Bajura Sappata 6 GAN BAHADUR BUDHA AABHARI BUDHA CHUDARI 911.4 Female 9 35970 7260012119 RAMU TAMATATA Mugu Seri 5 Padam Bahadur Tamata Manamata Tamata Bamkanda 912.6 Female 10 36673 7375025003 Akbar Od Baitadi Pancheswor 3 Ganesh ram od Kalawati od Kalauti 915.4 Male 11 40529 7335011133 PRAMOD KUMAR PANDIT Rautahat Dharhari 5 MISHRI PANDIT URMILA DEVI 915.8 Male 12 42683 7525055002 BIMALA RAI Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Man Bahadur Rai Gauri Maya Rai Ghodghad 915.9 Female 13 42758 7525055016 SABIN AALE MAGAR Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Raj Kumar Aale Magqar Devi Aale Magar Ghodghad 915.9 Male 14 42459 7217094014 SOBHA DHAKAL Dolakha GhangSukathokar 2 Bishnu Prasad Dhakal