Sharing Conservation Decisions: Current Issues and Future Strategies Edited by Alison Heritage & Jennifer Copithorne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Introduction to Odishan Temple Architecture

Odisha Review May - 2012 General introduction to Odishan Temple Architecture Anjaliprava Sahoo INTRODUCTION Sastras recognize three main styles of temple architecture known as the Nagara, the Dravida Temple is a ‘Place of Worship’. It is also called 1 the ‘House of God’. Stella Kramrisch has defined and the Vesara. temple as ‘Monument of Manifestation’ in her NAGARA TEMPLE STYLE book ‘The Hindu Temple’. The temple is one of Nagara types of temples are the typical the prominent and enduring symbols of Indian Northern Indian temples with curvilinear sikhara- culture: it is the most graphic expression of religious spire topped by amlakasila.2 This style was fervour, metaphysical values and aesthetic developed during A.D. 5th century. The Nagara aspiration. style is characterized by a beehive-shaped and The idea of temple originated centuries multi-layered tower, called ‘Sikhara’. The layers ago in the universal ancient conception of God in of this tower are topped by a large round cushion- a human form, which required a habitation, a like element called ‘amlaka’. The plan is based shelter and this requirement resulted in a structural on a square but the walls are sometimes so shrine. India’s temple architecture is developed segmented, that the tower appears circular in from the Sthapati’s and Silpi’s creativity. A small shape. Advancement in the architecture is found Hindu temple consists of an inner sanctum, the in temples belonging to later periods, in which the Garbha Griha or womb chamber; a small square central shaft is surrounded by many smaller room with completely plain walls having a single narrow doorway in the front, inside which the image is housed and other chambers which are varied from region to region according to the needs of the rituals. -

Circumambulation in Indian Pilgrimage: Meaning And

232 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & ENGINEERING RESEARCH, VOLUME 12, ISSUE 1, JANUARY-2021 ISSN 2229-5518 Circumambulation in Indian pilgrimage: Meaning and manifestation Santosh Kumar Abstract— Our ancient literature is full of examples where pilgrimage became an immensely popular way of achieving spiritual aims while walking. In India, many communities have attached spiritual importance to particular places or to the place where people feel a spiritual awakening. Circumambulation (pradakshina) around that sacred place becomes the key point of prayer and offering. All these circumambulation spaces are associated with the shrines or sacred places referring to auspicious symbolism. In Indian tradition, circumambulation has been practice in multiple scales ranging from a deity or tree to sacred hill, river, and city. The spatial character of the path, route, and street, shift from an inside dwelling to outside in nature or city, depending upon the central symbolism. The experience of the space while walking through sacred space remodel people's mental and physical character. As a result, not only the sacred space but their design and physical characteristics can be both meaningful and valuable to the public. This research has been done by exploring in two stage to finalize the conclusion, In which First stage will involve a literature exploration of Hindu and Buddhist scripture to understand the meaning and significance of circumambulation and in second, will investigate the architectural manifestation of various element in circumambulatory which help to attain its meaning and true purpose. Index Terms— Pilgrimage, Circumambulation, Spatial, Sacred, Path, Hinduism, Temple architecture —————————— —————————— 1 Introduction Circumambulation ‘Pradakshinā’, According to Rig Vedic single light source falling upon central symbolism plays a verses1, 'Pra’ used as a prefix to the verb and takes on the vital role. -

Perhaps Do a Series and Take One Particular Subject at a Time

perhaps do a series and take one particular subject at a time. Sadhguru just as I was coming to see you I saw this little piece in one of the newspapers which said that one doesn’t know about India being a super power but when it comes to mysticism, the world looks to Indian gurus as the help button on the menu. You’ve been all over the world and spoken at many international events, what is your take on all the divine gurus traversing the globe these days? India as a culture has invested more time, energy and human resource toward the spiritual development of human beings for a very long time. This can only happen when there is a stable society for long periods without much strife. While all other societies were raked by various types of wars, and revolutions, India remained peaceful for long periods of time. So they invested that time in spiritual development, and it became the day to day ethos of every Indian. The world looking towards India for spiritual help is nothing new. It has always been so in terms of exploring the inner spaces of a human being-how a human being is made, what is his potential, where could he be taken in terms of his experiences. I don’t think any culture has looked into this with as much depth and variety as India has. Mark Twain visited India and after spending three months and visiting all the right places with his guide he paid India the ultimate compliment when he said that anything that can ever be done by man or God has been done in this land. -

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

Art: Authenticity, Restoration, Forgery

UCLA Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press Title Art: Authenticity, Restoration, Forgery Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5xf6b5zd ISBN 978-1-938770-08-1 Author Scott, David A. Publication Date 2016-12-01 Data Availability The data associated with this publication are within the manuscript. Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOADS Art: Art: Authenticity, Restoration, ForgeryRestoration, Authenticity, Art: Forgery Authenticity, Restoration, Forgery David A. Scott his book presents a detailed account of authenticity in the visual arts from the Palaeolithic to the postmodern. The restoration of works Tof art can alter the perception of authenticity, and may result in the creation of fakes and forgeries. These interactions set the stage for the subject of this book, which initially examines the conservation perspective, then continues with a detailed discussion of what “authenticity” means, and the philosophical background. Included are several case studies that discuss conceptual, aesthetic, and material authenticity of ancient and modern art in the context of restoration and forgery. • Scott Above: An artwork created by the author as a conceptual appropriation of the original Egyptian faience objects. Do these copies possess the same intangible authenticity as the originals? Photograph by David A. Scott On front cover: Cast of author’s hand with Roman mask. Photograph by David A. Scott MLKRJBKQ> AO@E>BLILDF@> 35 MLKRJBKQ> AO@E>BLILDF@> 35 CLQPBK IKPQFQRQB LC AO@E>BLILDV POBPP CLQPBK IKPQFQRQB LC AO@E>BLILDV POBPP CIoA Press READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOADS Art: Authenticity, Restoration, Forgery READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOADS READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOADS Art: Authenticity, Restoration, Forgery David A. -

Redalyc.The Universalization of the Bhakti Yoga of Chaytania

VIBRANT - Vibrant Virtual Brazilian Anthropology E-ISSN: 1809-4341 [email protected] Associação Brasileira de Antropologia Brasil Silva da Silveira, Marcos The Universalization of the Bhakti Yoga of Chaytania Mahaprabhu. Ethnographic and Historic Considerations VIBRANT - Vibrant Virtual Brazilian Anthropology, vol. 11, núm. 2, diciembre, 2014, pp. 371-405 Associação Brasileira de Antropologia Brasília, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=406941918013 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative The Universalization of the Bhakti Yoga of Chaytania Mahaprabhu Ethnographic and Historic Considerations Marcos Silva da Silveira Abstract Inspired by Victor Turner’s concepts of structure and communitas, this article commences with an analysis of the Gaudiya Vaishnavas – worshipers of Radha, and Krishna Chaitanya Mahaprabhu followers. Secondly, we present data from ethnographic research conducted with South American devotees on pilgrimage to the ceremonial center ISCKON in Mayapur, West Bengal, during the year 1996, for a resumption of those initial considerations. The article seeks to demonstrate that the ritual injunction characteristic of Hindu sects, only makes sense from the individual experience of each devotee. Keywords: religion, Hinduism, New Age, Hare Krishna, ritual process Resumo Este artigo trata de revisitar o conceito consagrado de Victor Turner Estrutura – Communitas , tendo, como ponto de partida, uma análise de seus estudos de caso do Leste da Índia , em particular, entre os Gaudiya Vaishnavas – adoradores de Radha e Krishna, seguidores de Chaitanya Mahaprabhu. -

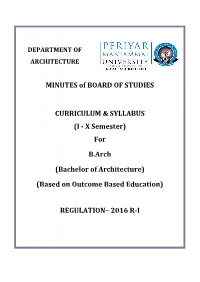

FOR B.ARCH - BACHELOR of ARCHITECTURE (FIVE YEAR - FULL TIME) REGULATION – 2016 -I (Applicable to the Students Admitted from the Academic Year 2015 -2016)

DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE MINUTES of BOARD OF STUDIES CURRICULUM & SYLLABUS (I - X Semester) For B.Arch (Bachelor of Architecture) (Based on Outcome Based Education) REGULATION– 2016 R-I REGULATIONS – 2015 (Revision 1) TABLE OF CONTENTS S.No Contents P.No 1. Institute Vision and Mission 1 2. Department Vision and Mission 2 3. Members of Board of studies 3 4. Department Vision and Mission Definition Process 5 5. Programme Educational Objectives (PEO) 6 6. PEO Process Establishment 7 7. Mapping of Institute Mission to PEO 8 8. Mapping of Department Mission to PEO 9 9. Programme Outcome (PO) 10 10. PO Process Establishment 11 11 Correlation between the POs and the PEOs 12 12 Curriculum development process 13 13. Faculty allotted for course development 14 14 Pre-requisite Course Chart 18 15 B. Arch – Curriculum 19 16 B. Arch – Syllabus 27 17 Overall course mapping with POS 145 Ninth Board Of Studies ii Dated:07/04/2016 PERIYAR MANIAMMAI UNIVERSITY Our University is committed to the following Vision, Mission and core values, which guide us in carrying out our Architecture Department mission and realizing our vision: INSTITUTION VISION To be a University of global dynamism with excellence in knowledge and innovation ensuring social responsibility for creating an egalitarian society. INSTITUTION MISSION UM1 Offering well balanced programmes with scholarly faculty and state-of-art facilities to impart high level of knowledge. UM2 Providing student - centered education and foster their growth in critical thinking, creativity, entrepreneurship, problem solving and collaborative work. UM3 Involving progressive and meaningful research with concern for sustainable development. -

(Korra): Holy Mt Kailash and Mansarovar Lake

27 - A/C, GANDHI NAGAR, JAMMU - 180004 (J&K) INDIA. Tele:- +91-191-2430662, 2452309, 2456656. Fax:- +91-191-2456656. Website: - www.mastertoursindia.com. Email: - [email protected] / [email protected] / [email protected] **OM NAMAH SHIVAYA** Holy Mt. KAILASH YATRA WITH NANDI & INNER PARIKRAMA (KORRA): HOLY MT KAILASH AND MANSAROVAR LAKE- AN INTRODUCTION: Holy Mt Kailash and Mansarowar Lake, center of creation & the Universe are as old as the creation. Thousands of Sages, Ordinary Mortals, Philosophers and even Gods had submerged in the blissful trance at the very sight of this divine grandeur. It is the MERU, SUMERU, SUSHUMNA, HEMADRI (Golden Mountain), RATNASANU (Jewel Peak), KARNIKACHALA (Lotus Mountain), AMARADRI, DEVA PARVATHA (Summit of Gods), GANAPARVATHA, AJATADRI (Silver Mountain). Regarded as SWAYAMBHU, the self-created one, everythingis said to emanate from here and finally returns here. Mind is the knot tying consciousness and matter-that is set free here. Famously known to be an abode of LORD SHIVA and his divine consort PARVATI, Mt. Kailash expounds the philosophy of PURUSHA and PRAKRITI-SHIVA and SHAKTI. The radiant SILVERLY summit is the throne of TRUTH, WISDOM and BLISS-SACHIDANANDAM. The primordial sound AUM (NADABINDU) from the tinkling anklets of LALITA PRAKRITI created the visible patterns of the universe and the vibrations (DVANI) from the feet of Lord Shiva (NATARAJA) weaved the essence of ATMAN, the ultimate truth. Mt. Kailash is considered to be the centre of Hindu philosophy and civilization. Kalpa Viruksha tree is supposed to adorn the slopes. South face is described as Sapphire, east as crystal, west as Ruby and north as Gold. -

Parikrama Booklet 2020

All glories to Çré Guru and Gauräìga Çré Navadvépa Maëòala Parikrama Gauräbda 534 (2020) 30th anniversary celebration Itinerary & General Information ISKCON International Society for Kåñëa Consciousness Sri Mayapur Chandrodaya Mandir Founder-Äcärya: His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedänta Swämi Prabhupäda 2 śrī-rādhāyāḥ praṇaya-mahimā kīdṛśo vānayaivā- svādyo yenādbhuta-madhurimā kīdṛśo vā madīyaḥ saukhyaṁ cāsyā mad-anubhavataḥ kīdṛśaṁ veti lobhāt tad-bhāvāḍhyaḥ samajani śacī-garbha-sindhau harīnduḥ Desiring to understand the glory of Rādhārāṇī’s love, the wonderful qualities in Him that She alone relishes through Her love, and the happiness She feels when She realizes the sweetness of His love, the Supreme Lord Hari, richly endowed with Her emotions, appeared from the womb of Śrīmatī Śacī-devī, as the moon appeared from the ocean. Sri Caitanya Caritamrta, 1.1.6 by Krsnadasa Kaviraj Goswami WELCOME TO SRI NAVADVIPA MANDALA PARIKRAMA 2020! 30TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION FESTIVAL HARE KRSNA! JAY GAUR! JAY NITAI! ALL GLORIES TO SRILA PRABHUPADA AND HIS FOLLOWERS! DEAR DEVOTEES, WELCOME HOME! ALL THE MAYAPUR DEVOTEES ARE VERY HAPPY TO SERVE YOU IN THIS WONDERFUL CELEBRATION OF 30 YEARS OF JOY, WHERE WE DO WHAT WE LOVE, JUST WALKING IN THE HOLY DHAM, IN THE ASSOCIATION OF LOVELY PEOPLE, CHANTING HARE KRSNA AND HAVING BHAGAVAT PRASADA! JAY HO! IN THE YEAR 1990 A VERY IMPORTANT CHANGE HAPPENED TO THE PARIKRAMA. ALL THE PILGRIMS HAD THE OPPORTUNITY TO STAY OVERNIGHT INSTEAD OF COMING BACK TO ISKCON MAYAPUR COM- PLEX IN THE END OF THE DAY. IT MAKES -

Common Elements of Dravidian Temple Architecture–A Study

IMPACT: International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Literature (IMPACT: IJRHAL) ISSN (P): 2347–4564; ISSN (E): 2321–8878 Vol. 7, Issue 2, Feb 2019, 583–588 © Impact Journals COMMON ELEMENTS OF DRAVIDIAN TEMPLE ARCHITECTURE–A STUDY D. Gandhimathi & K. Arul Mary Research Scholar, Department of History, PSGR Krishnammal College for Women, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India Research Scholar, Department of History, PSGR Krishnammal College for Women, Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, India Received: 17 Feb 2019 Accepted: 21 Feb2019 Published: 28 Feb 2019 ABSTRACT The South Indian temple architecture is known as Dravidian architecture. The South Indian temple has many architectural features. This article will explain the common elements of the Shivan temples in Tamilnadu. KEYWORDS: South Indian Temple, Dravidian Architecture, Architecture, Kongu Region INTRODUCTION Hindu temple architecture as the fundamental type of Hindu architecture has numerous assortments of style, however the fundamental idea of the Hindu sanctuary continues as before, with the basic element an internal sanctum, the garbha griha or belly chamber, where the essential Murti or the picture of a god is housed in a straightforward uncovered cell. On the outside, the garbhagriha is delegated by a pinnacle like shikhara, additionally called the vimana in the south. The place of worship assembling frequently incorporates a walking for parikrama (circumambulation), a mandapa gathering lobby, and at times an antarala waiting room and yard among garbhagriha and mandapa. There may promote mandapas or different structures, associated or disconnected, in enormous sanctuaries, together with other little sanctuaries in the compound. These terminologies are common across all temples built in Dravidian architecture and not specific to Shiva temples in Tamil Nadu. -

Socio-Cultural Influence in Built Forms of Kerala

International Journal for Social Studies Volume 01 Issue 01 Available at November 2015 http://edupediapublications.org/journals/index.php/IJSS Socio‐Cultural Influence in Built Forms of Kerala Akshay S Kumar Research Scholar, NIT Calicut, Kerala ABSTRACT kinds of influences, including Brahmanism, contributed to the cultural diffusion and Similarities in climate, it is natural that the architectural tradition. More homogeneous environmental characteristics of Kerala are artistic development may have rigorously more comparable with those of Southeast occurred around the 8th century as a result of Asia than with the rest of the Indian large-scale colonization by the Vedic subcontinent. Premodern architecture in (Sea Brahmans, which caused the decline of of Bengal) must have shared common Jainism and Buddhism. traditions with Southeast Asian architecture, which is wet tropical architecture. Because the Western Ghats isolated Kerala INTRODUCTION from the rest of the subcontinent, the infusion of Aryan culture into Kerala. It came only Kerala architecture is a kind of after Kerala had already developed an architectural style that is mostly found in independent culture, which can be as early as Indian state of Kerala and all the 1000 B.C. (Logan 1887). The Aryan architectural wonders of kerala stands out to immigration is believed to have started be ultimate testmonials for the ancient towards the end of the first millennium. vishwakarma sthapathis of kerala. Kerala's Christianity reached Kerala around 52 A.D. style of architecture is unique in India, in its through the apostle Thomas. The Jews in striking contrast to Dravidian architecture Kerala were once an affluent trading which is normally practiced in other parts of community on the Malabar. -

Forensics and Microscopy in Authenticating Works of Art Peter Paul Biro

Forensics and Microscopy in Authenticating Works of Art Peter Paul Biro 4 ISSUE 1 MARCH 2006 Fingerprints have been used around the world for identifying individuals since 1908. The availability of such evidence on works of art has been overlooked until the authentication of a Turner canvas in 1985. Since that case, a new methodology has been developed and the new discipline of forensic authentication was born. More recently, the concept of fingerprinting encompasses not only the marks left behind by our fingers but also the materials and working methods, widening the available ways to identify an artist. This innovative forensic approach has helped resolve equivocation and identify numerous important works of art as well as opening up a new field of research in art. bout 20 years ago, a client hang it as a demonstration. We gave walked into our Montreal in and a deal was struck. Some Aconservation laboratory with months later, a small area of the a large canvas he wanted cleaned and painting was tested to see how it restored. On first glance the painting behaved. After removing a small area seemed heavily overpainted and of overpainting on the sky we were recently so. The client shook his awestruck at the beauty of the head at the estimate for cleaning it, original surface coming to light. and said that it was not worth the Excitement grew and considerable cost as it was a wreck anyway. He effort was put into removing the asked whether our company would heavy coat of paint hiding the original buy the painting - to which he was surface.