What Is Operant Conditioning and How Does It Work?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Influence of Behavioural Psychology on Consumer Psychology and Marketing

This is a repository copy of The influence of behavioural psychology on consumer psychology and marketing. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/94148/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Wells, V.K. (2014) The influence of behavioural psychology on consumer psychology and marketing. Journal of Marketing Management, 30 (11-12). pp. 1119-1158. ISSN 0267-257X https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2014.929161 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Behavioural psychology, marketing and consumer behaviour: A literature review and future research agenda Victoria K. Wells Durham University Business School, Durham University, UK Contact Details: Dr Victoria Wells, Senior Lecturer in Marketing, Durham University Business School, Wolfson Building, Queens Campus, University Boulevard, Thornaby, Stockton on Tees, TS17 6BH t: +44 (0) 191 3345099, e: [email protected] Biography: Victoria Wells is Senior Lecturer in Marketing at Durham University Business School and Mid-Career Fellow at the Durham Energy Institute (DEI). -

Rule-Based Reinforcement Learning Augmented by External Knowledge

Rule-based Reinforcement Learning augmented by External Knowledge Nicolas Bougie12, Ryutaro Ichise1 1 National Institute of Informatics 2 The Graduate University for Advanced Studies Sokendai [email protected], [email protected] Abstract Learning from scratch and lack of interpretability impose some problems on deep reinforcement learning methods. Reinforcement learning has achieved several suc- Randomly initializing the weights of a neural network is in- cesses in sequential decision problems. However, efficient. Furthermore, this is likely intractable to train the these methods require a large number of training model in many domains due to a large amount of required iterations in complex environments. A standard data. Additionally, most RL algorithms cannot introduce ex- paradigm to tackle this challenge is to extend rein- ternal knowledge limiting their performance. Moreover, the forcement learning to handle function approxima- impossibility to explain and understand the reason for a de- tion with deep learning. Lack of interpretability cision restricts their use to non-safety critical domains, ex- and impossibility to introduce background knowl- cluding for example medicine or law. An approach to tackle edge limits their usability in many safety-critical these problems is to combine simple reinforcement learning real-world scenarios. In this paper, we study how techniques and external knowledge. to combine reinforcement learning and external A powerful recent idea to address the problem of computa- knowledge. We derive a rule-based variant ver- tional expenses is to modularize the model into an ensemble sion of the Sarsa(λ) algorithm, which we call Sarsa- of experts [Lample and Chaplot, 2017], [Bougie and Ichise, rb(λ), that augments data with complex knowledge 2017]. -

Personality and Individual Differences 128 (2018) 162–169

Personality and Individual Differences 128 (2018) 162–169 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Personality and Individual Differences journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/paid Risk as reward: Reinforcement sensitivity theory and psychopathic T personality perspectives on everyday risk-taking ⁎ Liam P. Satchella, , Alison M. Baconb, Jennifer L. Firthc, Philip J. Corrd a School of Law and Criminology, University of West London, United Kingdom b School of Psychology, Plymouth University, United Kingdom c Department of Psychology, Nottingham Trent University, United Kingdom d Department of Psychology, City, University of London, United Kingdom ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: This study updates and synthesises research on the extent to which impulsive and antisocial disposition predicts Personality everyday pro- and antisocial risk-taking behaviour. We use the Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory (RST) of Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory personality to measure approach, avoidance, and inhibition dispositions, as well as measures of Callous- Psychopathy Unemotional and psychopathic personalities. In an international sample of 454 respondents, results showed that Callous-unemotional traits RST, psychopathic personality, and callous-unemotional measures accounted for different aspects of risk-taking Risk-taking behaviour. Specifically, traits associated with ‘fearlessness’ related more to ‘prosocial’ (recreational and social) risk-taking, whilst traits associated with ‘impulsivity’ related more to ‘antisocial’ (ethical and health) risk-taking. Further, we demonstrate that psychopathic personality may be demonstrated by combining the RST and callous- unemotional traits (high impulsivity, callousness, and low fear). Overall this study showed how impulsive, fearless and antisocial traits can be used in combination to identify pro- and anti-social risk-taking behaviours; suggestions for future research are indicated. 1. -

Tactics of Impression Management: Relative Success on Workplace Relationship Dr Rajeshwari Gwal1 ABSTRACT

The International Journal of Indian Psychology ISSN 2348-5396 (e) | ISSN: 2349-3429 (p) Volume 2, Issue 2, Paper ID: B00362V2I22015 http://www.ijip.in | January to March 2015 Tactics of Impression Management: Relative Success on Workplace Relationship Dr Rajeshwari Gwal1 ABSTRACT: Impression Management, the process by which people control the impressions others form of them, plays an important role in inter-personal behavior. All kinds of organizations consist of individuals with variety of personal characteristics; therefore those are important to manage them effectively. Identifying the behavior manner of each of these personal characteristics, interactions among them and interpersonal relations are on the basis of the impressions given and taken. Understanding one of the important determinants of individual’s social relations helps to get a broader insight of human beings. Employees try to sculpture their relationships in organizational settings as well. Impression management turns out to be a continuous activity among newcomers, used in order to be accepted by the organization, and among those who have matured with the organization, used in order to be influential (Demir, 2002). Keywords: Impression Management, Self Promotion, Ingratiation, Exemplification, Intimidation, Supplication INTRODUCTION: When two individuals or parties meet, both form a judgment about each other. Impression Management theorists believe that it is a primary human motive; both inside and outside the organization (Provis,2010) to avoid being evaluated negatively (Jain,2012). Goffman (1959) initially started with the study of impression management by introducing a framework describing the way one presents them and how others might perceive that presentation (Cole, Rozelle, 2011). The first party consciously chooses a behavior to present to the second party in anticipation of a desired effect. -

Action to End Child Sexual Abuse and Exploitation

ACTION TO END CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE AND EXPLOITATION Published by UNICEF Child Protection Section Programme Division 3 United Nations Plaza New York, NY 10017 Email: [email protected] Website: www.unicef.org © United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) December 2020. Permission is required to reproduce any part of this publication. Permission will be freely granted to educational or non-profit organizations. For more information on usage rights, please contact: [email protected] Cover photo: © UNICEF/UNI303881/Zaidi Design and layout by Big Yellow Taxi, Inc. Suggested citation: United Nations Children’s Fund (2020) Action to end child sexual abuse and exploitation, UNICEF, New York This publication has been produced with financial support from the End Violence Fund. However, the opinions, findings, conclusions, and recommendations expressed herein do not necessarily reflect those of the End Violence Fund. Click on section bars to navigate publication CONTENTS 1. Introduction ............................................3 6. Service delivery ...................................21 2. A Global Problem...................................5 7. Social & behavioural change ................27 3. Building on the evidence .................... 11 8. Gaps & challenges ...............................31 4. A Theory of Change ............................13 Endnotes .................................................32 5. Enabling National Environments ..........15 1 Ending Child Sexual Abuse and Exploitation: A Review of the Evidence ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS -

Fact Sheet - Reinforcement

FACT SHEET - REINFORCEMENT Positive Reinforcement Because many children with autism have difficulty with communication, play skills, and socialization, it is often difficult to motivate them to engage in activities that incorporate these skills. Positive reinforcement can provide additional motivation to help shape and increase developmentally approriate behaviors. A positive reinforcer is anything that is added following a behavior that increases the likelihood of the behavior occuring again in the future. Rewards are often given to children when they engage in desirable behaviors, but if the reward does Contact Information not cause those behaviors to increase in the future, then the reward is not actually a Website: positive reinforcer. www.coe.fau.edu/card/ Various Forms of Reinforcement Boca Raton Campus 777 Glades Road Natural Reinforcement: A child’s positive behaviors and social interactions Boca Raton, FL. 33431 are reinforced naturally. The natural consequences of positive behaviors become reinforcing themselves. Successful interactions become motivating to the child. Main Line: 561/ 297-2023 Toll Free: 1-888-632-6395 Examples: Fax: 561/297-2507 ♦ There is a ball out of reach for a child. The child says, “Ball,” and an adult Port St Lucie Campus hands the ball to the child. Access to the ball is reinforcing and increases the likelihood of the child requesting “ball” in the future. 500 NW California Blvd. ♦ A child is struggling with a difficult puzzle. The child says, “Help,” and an Port St Lucie, FL. 34986 adult helps the child. Completion of the puzzle is reinforcing. This successful interaction increases the likelihood of the child attempting puzzles Main Line: 561/ 297-2023 in the future and requesting help when needed. -

What's Wrong with the Sociology of Punishment?1

1 What’s Wrong with the Sociology of Punishment?1 John Braithwaite Australian National University Abstract The sociology of punishment is seen through the work of David Garland, as contributing useful insights, but less than it might because of its focus on societal choices of whether and how to punish instead of on choices of whether to regulate by punishment or by a range of other important strategies. A problem in Garland’s genealogical method is that branches of the genealogy are sawn off – the branches where the chosen instruments of regulation decentre punishment. This blinds us to the hybridity of predominantly punitive regulation of crime in the streets that is reshaped by more risk- preventive and restorative technologies of regulation for crime in the suites, and vice versa. Such hybridity is illustrated by contrasting the regulation of pharmaceuticals with that of “narcotics” and by juxtaposing the approaches to a variety of business regulatory challenges. A four-act drama of Rudoph Guiliani’s career as a law enforcer - Wall Street prosecutor (I), “zero-tolerance” mayor (II), Mafia enforcement in New York (III), and Rudi the Rock of America’s stand against terrorism (IV) - is used to illustrate the significance of the hybridity we could be more open to seeing. Guiliani takes criminal enforcement models into business regulation and business regulatory models to street crime. The weakness of a genealogical approach to punishment can be covered by the strengths of a history of regulation that is methodologically committed to synoptically surveying all the important techniques of regulation deployed to control a specific problem (like drug abuse). -

Punishment on Trial √ Feel Guilty When You Punish Your Child for Some Misbehavior, but Have Ennio Been Told That Such Is Bad Parenting?

PunishmentPunishment onon TrialTrial Cipani PunishmentPunishment onon TrialTrial Do you: √ believe that extreme child misbehaviors necessitate physical punishment? √ equate spanking with punishment? √ believe punishment does not work for your child? √ hear from professionals that punishing children for misbehavior is abusive and doesn’t even work? Punishment on Trial Punishment on √ feel guilty when you punish your child for some misbehavior, but have Ennio been told that such is bad parenting? If you answered “yes” to one or more of the above questions, this book may Cipani be just the definitive resource you need. Punishment is a controversial topic that parents face daily: To use or not to use? Professionals, parents, and teachers need answers that are based on factual information. This book, Punishment on Trial, provides that source. Effective punishment can take many forms, most of which do not involve physical punishment. This book brings a blend of science, clinical experience, and logic to a discussion of the efficacy of punishment for child behavior problems. Dr. Cipani is a licensed psychologist with over 25 years of experience working with children and adults. He is the author of numerous books on child behavior, and is a full professor in clinical psychology at Alliant International University in Fresno, California. 52495 Context Press $24.95 9 781878 978516 1-878978-51-9 A Resource Guide to Child Discipline i Punishment on Trial ii iii Punishment on Trial Ennio Cipani Alliant International University CONTEXT PRESS Reno, Nevada iv ________________________________________________________________________ Punishment on Trial Paperback pp. 137 Distributed by New Harbinger Publications, Inc. ________________________________________________________________________ Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Cipani, Ennio. -

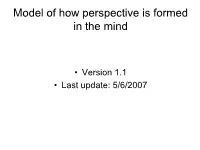

Model of How Perspective Is Formed in the Mind

Model of how perspective is formed in the mind • Version 1.1 • Last update: 5/6/2007 Simple model of information processing, perception generation, and behavior Feedback can distort data from input Information channels Data Emotional Filter Cognitive Filter Input Constructed External Impact Analysis Channels Perspective information “How do I feel about it?” “What do I think about it? ” “How will it affect Sight Perceived Reality i.e. news, ETL Process ETL Process me?” Hearing environment, Take what feels good, Take what seems good, Touch Word View etc. reject the rest or flag reject the rest or flag Smell as undesirable. as undesirable. Taste Modeling of Results Action possible behaviors Motivation Impact on Behavior “What might I do?” Anticipation of Gain world around Or you “I do something” Options are constrained Fear of loss by emotional and cognitive filters i.e bounded by belief system Behavior Perspective feedback feedback World View Conditioning feedback Knowledge Emotional Response Information Information Experience Experience Filtered by perspective and emotional response conditioning which creates “perception” Data Data Data Data Data Data Data Data Data Newspapers Television Movies Radio Computers Inter-person conversations Educational and interactions Magazines Books Data sources system Internet Data comes from personal experience, and “information” sources. Note that media is designed to feed preconceived “information” directly into the consciousness of the populace. This bypasses most of the processing, gathering, manipulating and organizing of data and hijacks the knowledge of the receiver. In other words, the data is taken out of context or in a pre selected context. If the individual is not aware of this model and does not understand the process of gathering, manipulating and organizing data in a way that adds to the knowledge of the receiver, then the “information” upon which their “knowledge” is based can enter their consciousness without the individual being aware of it or what impact it has on their ability to think. -

Definitions of Child Abuse and Neglect

STATE STATUTES Current Through March 2019 WHAT’S INSIDE Defining child abuse or Definitions of Child neglect in State law Abuse and Neglect Standards for reporting Child abuse and neglect are defined by Federal Persons responsible for the child and State laws. At the State level, child abuse and neglect may be defined in both civil and criminal Exceptions statutes. This publication presents civil definitions that determine the grounds for intervention by Summaries of State laws State child protective agencies.1 At the Federal level, the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment To find statute information for a Act (CAPTA) has defined child abuse and neglect particular State, as "any recent act or failure to act on the part go to of a parent or caregiver that results in death, https://www.childwelfare. serious physical or emotional harm, sexual abuse, gov/topics/systemwide/ or exploitation, or an act or failure to act that laws-policies/state/. presents an imminent risk of serious harm."2 1 States also may define child abuse and neglect in criminal statutes. These definitions provide the grounds for the arrest and prosecution of the offenders. 2 CAPTA Reauthorization Act of 2010 (P.L. 111-320), 42 U.S.C. § 5101, Note (§ 3). Children’s Bureau/ACYF/ACF/HHS 800.394.3366 | Email: [email protected] | https://www.childwelfare.gov Definitions of Child Abuse and Neglect https://www.childwelfare.gov CAPTA defines sexual abuse as follows: and neglect in statute.5 States recognize the different types of abuse in their definitions, including physical abuse, The employment, use, persuasion, inducement, neglect, sexual abuse, and emotional abuse. -

The Building Blocks of Treatment in Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy

Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci Vol 46 No. 4 (2009) 245–250 The Building Blocks of Treatment in Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Jonathan D. Huppert, PhD Department of Psychology, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel Abstract: Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a set of treatments that focus on altering thoughts, sensations, emo- tions and behaviors by addressing identified maintenance mechanisms such as distorted thinking or avoidance. The current article describes the history of CBT and provides a description of many of the basic techniques used in CBT. These include: psychoeducation, self-monitoring, cognitive restructuring, in vivo exposure, imaginal exposure, and homework assignments. Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is probably progress has been made in understanding the psy- better called cognitive and behavioral therapies, chological mechanisms involved in treatment (e.g., given that there are many treatments and traditions 10), though there is still much to understand. that fall under the rubric of CBT. These therapies The basic tenets of CBT theory of mental illness have different emphases on theory (e.g., cognitive is that psychopathology is comprised of maladap- versus behavioral) and application (e.g., practical tive associations among thoughts, behaviors and vs. theoretical). Historically, behavior therapy de- emotions that are maintained by cognitive (at- veloped out of learning theory traditions of Pavlov tention, interpretation, memory) and behavioral (1) and Skinner (2), both of whom considered processes (avoidance, reinforcement, etc.). Within learning’s implications for psychopathology. More CBT theories, there are different emphases on direct clinical applications of behavioral prin- aspects of the characteristics of psychopathology ciples were developed by Mowrer (3), Watson and and their maintenance mechanisms (e.g., 11–14). -

Throwing More Light on the Dark Side of Personality: a Re-Examination of Reinforcement

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Broerman, R. L., Ross, S. & Corr, P. J. (2014). Throwing more light on the dark side of psychopathy: An extension of previous findings for the revised Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory. Personality and Individual Differences, 68, pp. 165-169. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.04.024 This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/16257/ Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.04.024 Copyright and reuse: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] Throwing More Light on the Dark Side of Personality: A Re-examination of Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory in Primary and Secondary Psychopathy Scales Broerman, R. L. Ross, S. R. Corr, P. J. Introduction Due to researchers’ differing opinions regarding the construct of psychopathy, the distinction between primary and secondary psychopathy, though it has long been recognized to exist, has yet to be fully understood. This distinction, originally proposed by Karpman (1941, 1948), suggests two separate etiologies leading to psychopathy. Whereas primary psychopathy stems from genetic influences resulting in emotional deficits, secondary psychopathy is associated with environmental factors such as abuse (Lee & Salekin, 2010). Additionally, primary psychopathy is characterized by lack of fear/anxiety, secondary psychopathy is thought more to represent a vulnerability to experience higher levels of negative affect in general (Vassileva, Kosson, Abramowitz, & Conrad, 2005).