Finland—Selected Issues and Statistical Appendix

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Methods and Philosophy of Statistical Process Control

5Methods and Philosophy of Statistical Process Control CHAPTER OUTLINE 5.1 INTRODUCTION 5.4 THE REST OF THE MAGNIFICENT 5.2 CHANCE AND ASSIGNABLE CAUSES SEVEN OF QUALITY VARIATION 5.5 IMPLEMENTING SPC IN A 5.3 STATISTICAL BASIS OF THE CONTROL QUALITY IMPROVEMENT CHART PROGRAM 5.3.1 Basic Principles 5.6 AN APPLICATION OF SPC 5.3.2 Choice of Control Limits 5.7 APPLICATIONS OF STATISTICAL PROCESS CONTROL AND QUALITY 5.3.3 Sample Size and Sampling IMPROVEMENT TOOLS IN Frequency TRANSACTIONAL AND SERVICE 5.3.4 Rational Subgroups BUSINESSES 5.3.5 Analysis of Patterns on Control Charts Supplemental Material for Chapter 5 5.3.6 Discussion of Sensitizing S5.1 A SIMPLE ALTERNATIVE TO RUNS Rules for Control Charts RULES ON THEx CHART 5.3.7 Phase I and Phase II Control Chart Application The supplemental material is on the textbook Website www.wiley.com/college/montgomery. CHAPTER OVERVIEW AND LEARNING OBJECTIVES This chapter has three objectives. The first is to present the basic statistical control process (SPC) problem-solving tools, called the magnificent seven, and to illustrate how these tools form a cohesive, practical framework for quality improvement. These tools form an impor- tant basic approach to both reducing variability and monitoring the performance of a process, and are widely used in both the analyze and control steps of DMAIC. The second objective is to describe the statistical basis of the Shewhart control chart. The reader will see how decisions 179 180 Chapter 5 ■ Methods and Philosophy of Statistical Process Control about sample size, sampling interval, and placement of control limits affect the performance of a control chart. -

Using Likelihood Ratios to Compare Run Chart Rules on Simulated Data Series

RESEARCH ARTICLE Diagnostic Value of Run Chart Analysis: Using Likelihood Ratios to Compare Run Chart Rules on Simulated Data Series Jacob Anhøj* Centre of Diagnostic Evaluation, Rigshospitalet, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark * [email protected] Abstract Run charts are widely used in healthcare improvement, but there is little consensus on how to interpret them. The primary aim of this study was to evaluate and compare the diagnostic a11111 properties of different sets of run chart rules. A run chart is a line graph of a quality measure over time. The main purpose of the run chart is to detect process improvement or process degradation, which will turn up as non-random patterns in the distribution of data points around the median. Non-random variation may be identified by simple statistical tests in- cluding the presence of unusually long runs of data points on one side of the median or if the graph crosses the median unusually few times. However, there is no general agreement OPEN ACCESS on what defines “unusually long” or “unusually few”. Other tests of questionable value are Citation: Anhøj J (2015) Diagnostic Value of Run frequently used as well. Three sets of run chart rules (Anhoej, Perla, and Carey rules) have Chart Analysis: Using Likelihood Ratios to Compare been published in peer reviewed healthcare journals, but these sets differ significantly in Run Chart Rules on Simulated Data Series. PLoS their sensitivity and specificity to non-random variation. In this study I investigate the diag- ONE 10(3): e0121349. doi:10.1371/journal. pone.0121349 nostic values expressed by likelihood ratios of three sets of run chart rules for detection of shifts in process performance using random data series. -

Approaches for Detection of Unstable Processes: a Comparative Study Yerriswamy Wooluru J S S Academy of Technical Education, Bangalore, India, [email protected]

Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods Volume 14 | Issue 2 Article 17 11-1-2015 Approaches for Detection of Unstable Processes: A Comparative Study Yerriswamy Wooluru J S S Academy of Technical Education, Bangalore, India, [email protected] D. R. Swamy J S S Academy of Technical Education, Bangalore, India P. Nagesh JSS Centre for Management Studies, Mysore, Indi Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/jmasm Part of the Applied Statistics Commons, Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons, and the Statistical Theory Commons Recommended Citation Wooluru, Yerriswamy; Swamy, D. R.; and Nagesh, P. (2015) "Approaches for Detection of Unstable Processes: A Comparative Study," Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods: Vol. 14 : Iss. 2 , Article 17. DOI: 10.22237/jmasm/1446351360 Available at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/jmasm/vol14/iss2/17 This Regular Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Open Access Journals at DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@WayneState. Approaches for Detection of Unstable Processes: A Comparative Study Cover Page Footnote This work is supported by JSSMVP Mysore. I, sincerely thank to my Guide Dr.Swamy D.R, Professor and Head of the Department, Industrial Engineering &Management, JSSATE Bangalore and Co-Guide Dr P.Nagesh, Professor, Department of Management studies, SJCE, Mysore. This regular article is available in Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/jmasm/vol14/ iss2/17 Journal of Modern Applied Statistical Methods Copyright © 2015 JMASM, Inc. November 2015, Vol. 14 No. -

Run Charts Revisited: a Simulation Study of Run Chart Rules for Detection of Non- Random Variation in Health Care Processes

RESEARCH ARTICLE Run Charts Revisited: A Simulation Study of Run Chart Rules for Detection of Non- Random Variation in Health Care Processes Jacob Anhøj1*, Anne Vingaard Olesen2 1. Rigshospitalet, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2. University of Aalborg, Danish Center for Healthcare Improvements, Department of Business and Management, Aalborg, Denmark *[email protected] Abstract Background: A run chart is a line graph of a measure plotted over time with the median as a horizontal line. The main purpose of the run chart is to identify process improvement or degradation, which may be detected by statistical tests for non- random patterns in the data sequence. Methods: We studied the sensitivity to shifts and linear drifts in simulated processes using the shift, crossings and trend rules for detecting non-random variation in run charts. Results: The shift and crossings rules are effective in detecting shifts and drifts in OPEN ACCESS process centre over time while keeping the false signal rate constant around 5% Citation: Anhøj J, Olesen AV (2014) Run Charts Revisited: A Simulation Study of Run Chart Rules and independent of the number of data points in the chart. The trend rule is virtually for Detection of Non-Random Variation in Health useless for detection of linear drift over time, the purpose it was intended for. Care Processes. PLoS ONE 9(11): e113825. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0113825 Editor: Robert K. Hills, Cardiff University, United Kingdom Received: February 24, 2014 Accepted: November 1, 2014 Introduction Published: November 25, 2014 Plotting measurements over time turns out, in my view, to be one of the most Copyright: ß 2014 Anhøj, Olesen. -

A Guide to Creating and Interpreting Run and Control Charts Turning Data Into Information for Improvement Using This Guide

Institute for Innovation and Improvement A guide to creating and interpreting run and control charts Turning Data into Information for Improvement Using this guide The NHS Institute has developed this guide as a reminder to commissioners how to create and analyse time-series data as part of their improvement work. It should help you ask the right questions and to better assess whether a change has led to an improvement. Contents The importance of time based measurements .........................................4 Run Charts ...............................................6 Control Charts .......................................12 Process Changes ....................................26 Recommended Reading .........................29 The Improving immunisation rates importance Before and after the implementation of a new recall system This example shows yearly figures for immunisation rates of time-based before and after a new system was introduced. The aggregated measurements data seems to indicate the change was a success. 90 Wow! A “significant improvement” from 86% 79% to 86% -up % take 79% 75 Time 1 Time 2 Conclusion - The change was a success! 4 Improving immunisation rates Before and after the implementation of a new recall system However, viewing how the rates have changed within the two periods tells a 100 very different story. Here New system implemented here we see that immunisation rates were actually improving until the new 86% – system was introduced. X They then became worse. 79% – Seeing this more detailed X 75 time based picture prompts a different response. % take-up Now what do you conclude about the impact of the new system? 50 24 Months 5 Run Charts Elements of a run chart A run chart shows a measurement on the y-axis plotted over time (on the x-axis). -

Recent Debates on Monetary Condition and Inflation Pressures on the Mainland Call for an Analysis on the Inflation Dynamics and Their Main Determinants

Research Memorandum 04/2005 March 2005 MONEY AND INFLATION IN CHINA Key points: • Recent debates on monetary condition and inflation pressures on the Mainland call for an analysis on the inflation dynamics and their main determinants. A natural starting point for the econometric analysis of monetary and inflation developments is the notion of monetary equilibrium. • This paper presents an estimate of the long-run demand for money in China. The estimated long-run income elasticity is rather stable over time and consistent with that estimated in earlier studies. • The difference between the estimated demand for money and the actual money stock provides an estimate of monetary disequilibria. These seem to provide leading information about CPI inflation in the sample period. At the current conjuncture, the measure suggests that monetary conditions have tightened since the macroeconomic adjustment started in early 2004. • Additionally, an error-correction model based on the long-run money demand function offers insights into the short-run and long-run inflation dynamics. Specifically: ¾ Over the longer term, inflation is mostly caused by monetary expansion. ¾ The price level responds to monetary shocks with lags and on average it takes about 20 quarters for the impact of a permanent monetary shock to peak. This suggests the need for early policy actions to curb inflation pressure given the long policy operation lag. Prepared by : Stefan Gerlach and Janet Kong Research Department Hong Kong Monetary Authority I. INTRODUCTION Concerns have been raised recently about overheating pressures in the economy of Mainland China (see, for example, Kalish 2004, Bradsher 2004, and Ignatius 2004). -

Stat 3411 Fall 2012 Exam 1

Stat 3411 Fall 2012 Exam 1 The questions will cover material from assignments, classroom examples, posted lecture notes, and the text reading material corresponding to the points covered in class. If there is a concept in the book that is not covered in the posted lecture notes, in class, or on assignments, I won't ask you anything about that topic. The questions will be chosen so that the required arithmetic and other work is minimal in order to fit questions into 55 minutes. Plotting, if any, you are asked to do will be very quick and simple. o See problem 6 on the posted chapter 3 sample exam questions. Make use of information posted on the class web site, http://www.d.umn.edu/~rregal/stat3411.html Stat 3411 Syllabus Notes NIST Engineering Statistics Handbook National Institute of Standards and Technology Assignments Data Sets, Statistics Primer, and Examples Project Exam Information Sample Exam Questions From the Notes link: Chapters 1 and 2 1.1 Engineering Statistics: What and Why 1.2 Basic Terminology 1.3 Measurement: Its Importance and Difficulty 1.4 Mathematical Models, Reality, and Data Analysis 2.1 General Principles in the Collection of Engineering Data 2.2 Sampling in Enunerative Studies 2.3 Principles for Effective Experimentation 2.4 Some Common Experimental Designs 2.5 Collecting Engineering Data Outline Notes Guitar Strings: Use of Experimental Design Sticker Adhesion: Use of Models Testing Golf Clubs Observational and Experimental Studies: Ford Explorer Rollovers Excel: Factorial Randomization Table B1: Random Digits The first two chapters concerned basic ideas that go into designing studies and collecting data. -

How Do We Know That a Change Is an Improvement?

How Do We Know that a Change is an Improvement? Presenters: Farashta Zainal, MBA, PMP Senior Improvement Advisor Joy Dionisio, MPH Improvement Advisor June 30, 2020 Webinar Instructions Figure 1 Figure 2 ***There are two options to Switch Connection to telephone audio. 2 Webinar Instructions • All participants have been muted Figure 1 to eliminate any possible noise/ interference/distraction. • Please take a moment and open your chat box by clicking the chat icon found at the bottom of your screen and as shown in Figure 1. • Be sure to select “All Participants” when sending a message. • If you have any questions, please type your questions into the chat box, and they will be answered throughout the presentation. Conflict of Interest All presenters have signed a conflict of interest form and have declared that there is no conflict of interest and nothing to disclose for this presentation. 4 Learning Objectives 1 2 3 Understand the Learn how to Understand the importance of construct run role of data context to charts using measurement in interpret current special cause improvement and be able to develop data variation a data collection plan and strategies for implementing it 5 Review Session 1 Model for Improvement What are we trying to accomplish? How will we know that a change is an improvement? What changes can we make that will result in improvement? Act Plan Study Do From Associates in Process Improvement. 6 Review Session I – Aim Statement • Aim statements should meet the SMART criteria: • Specific • Measureable • Achievable Ambitious -

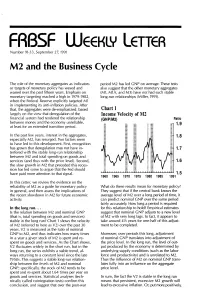

M2 and the Business Cycle

FRBSF WEEKLY LETTER Number 91~33, September 27, 1991 M2 and the Business Cycle The role of the monetary aggregates as indicators period M2 has led GNP on average. These tests or targets of monetary policy has waxed and also suggest that the other monetary aggregates waned over the past fifteen years. Emphasis on (M1, M1A, and M3) have not had such stable monetary targeting reached a high in 1979-1982, long-run relationships (Miller, 1991). when the Federal Reserve explicitly targeted M1 in implementing its anti-inflation policies. After that, the aggregates were de-emphasized, based Chart 1 largely on the view that deregulation of the Income Velocity of M2 financial system had rendered the relationship (GNP/M2) Ratio between money and the economy unreliable, 1.9 at least for an extended transition period. In the past few years, interest in the aggregates, 1.8 especially M2, has resurged. Two factors seem to have led to this development. First, recognition has grown that deregulation may not have in 1.7 terfered with the stable long-run relationship between M2 and total spending on goods and services (and thus with the price level). Second, 1.6 the slow growth in M2 that preceded this reces sion has led some to argue that the Fed should have paid more attention to that signal. 1.5 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1991 In this Letter, we review the evidence on the reliability of M2 as a guide for monetary policy What do these results mean for monetary policy? in general, and then assess the implications of They suggest that if the central bank knows the the recent slowdown in M2 for future economic average level of M2 over a long period of time, it activity. -

Basic Tools for Process Improvement

Basic Tools for Process Improvement Module 9 RUN CHART RUN CHART 1 Basic Tools for Process Improvement What is a Run Chart? A Run Chart is the most basic tool used to display how a process performs over time. It is a line graph of data points plotted in chronological order—that is, the sequence in which process events occurred. These data points represent measurements, counts, or percentages of process output. Run Charts are used to assess and achieve process stability by highlighting signals of special causes of variation (Viewgraph 1). Why should teams use Run Charts? Using Run Charts can help you determine whether your process is stable (free of special causes), consistent, and predictable. Unlike other tools, such as Pareto Charts or Histograms, Run Charts display data in the sequence in which they occurred. This enables you to visualize how your process is performing and helps you to detect signals of special causes of variation. A Run Chart also allows you to present some simple statistics related to the process: Median: The middle value of the data presented. You will use it as the Centerline on your Run Chart. Range: The difference between the largest and smallest values in the data. You will use it in constructing the Y-axis of your Run Chart. You can benefit from using a Run Chart whenever you need a graphical tool to help you (Viewgraph 2) Understand variation in process performance so you can improve it. Analyze data for patterns that are not easily seen in tables or spreadsheets. Monitor process performance over time to detect signals of changes. -

CHAPTER 3: SIMPLE EXTENSIONS of CONTROL CHARTS 1. Introduction

CHAPTER 3: SIMPLE EXTENSIONS OF CONTROL CHARTS 1. Introduction: Counting Data and Other Complications The simple ideas of statistical control, normal distribution, control charts, and data analysis introduced in Chapter 2 give a good start on learning to analyze data -- and hence ultimately to improve quality. But as you try to apply these ideas, you will sometimes encounter challenging complications that you won't quite know how to deal with. In Chapter 3, we consider several common complications and show how slight modifications or extensions of the ideas of Chapter 2 can be helpful in dealing with them. As usual, we shall rely heavily on examples. So long as the data approximately conform to randomness and normality, as in all but one example of Chapter 2, we have a system both for data analysis and quality improvement. To see whether the data do conform, we have these tools: • The run chart gives a quick visual indication of whether or not the process is in statistical control. • The runs count gives a numerical check on the visual impression from the run chart. • If the process is in control, we can check to see whether the histogram appears to be roughly what we would expect from an underlying normal distribution. • If we decide that the process is in control and approximately normally distributed, then a control chart, histogram, and summary statistical measure tell us what we need from the data: • Upper and lower control limits on the range of variation of future observations. • If future observations fall outside those control limits -- are "outliers" -- we can search for possible special causes impacting the process. -

CHAPTER 9 2Nd Edition, Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2019

Source:Lloyd. R. Quality Health Care: A Guide to Developing and Using Indicators CHAPTER 9 2nd Edition, Jones & Bartlett Learning, 2019. Understanding Variation with Shewhart Charts e details related to these dierences are dis- ▸ Run Charts versus cussed in the remaining sections of this chapter. Shewhart Charts For many teams just beginning their quality mea- ▸ What Is a Shewhart surement journey (QMJ) the run chart provides an excellent starting point. It is easy to construct Chart? with paper and pencil, it does not require a so- Like run charts, Shewhart charts are graphic ware package in order to make one, and it can displays of process variation as it lays itself out be used with any type of data (i.e., time, money, over time. FIGURE 91 shows the basic elements of counts of errors, percentages, rates, scores, or days a Shewhart chart and one of the tests to identify between adverse events). Also, the four run chart a special cause (i.e., a data point exceeded the rules are easy to understand and apply. So, why upper control limit [UCL], signaling too much would I want to use a Shewhart chart instead of a variation in the data, which, by the way, you run chart?1 ere are basically three reasons why should recognize as an astronomical data point Shewhart charts are preferable over run charts: on the run chart). A run chart and a Shewhart 1. Shewhart charts are more sensitive chart look similar in that the indicator of interest than run charts. and its values are plotted on the vertical or y 2.