A Guide for Teachers November 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

He's Britain's Most Successful Jazz Artist Ever, Is Married to Sophie

C OOKIN’ WITH JAZZ He’s Britain’s most successful jazz artist ever, is married to Sophie Dahl and puts on electric stage shows complete with exploding pianos. Is there no stopping Jamie Cullum, asks Christopher Silvester Photographs by Olaf Wipperfürth Styled by Gianluca Longo 2 2 ES MAGAZINE standard.co.uk/lifestyle Jamie wears suit jacket, £935, Prada (020 7647 5000). Shirt, £99.99, Hugo Boss (020 7554 5700). Jeans, £19.99, Uniqlo (020 7290 8090). Chiffre Rouge A05 watch, £2,500, Christian Dior (020 7172 0172) standard.co.uk/lifestyle ES MAGAZINE 2 3 t is 6.30pm and Jamie Cullum is home and I was trying to learn it, and my mum brother and I would make drum kits out of eating his first meal of the day, said it was an Elton John song. I didn’t believe bins, saucepan lids, cardboard boxes and stuff. a chicken croque monsieur. Even her. That’s when she dug out Tumbleweed And we’d record them. I think when I got to the so, he urges me to take a couple Connection and those early Elton John records. piano, because I hadn’t had years of being told of mouthfuls. So this is the It opened up a whole new world.’ how to do it properly, when I started messing musician’s diet that keeps him so Jamie’s mother is Anglo-Burmese, although around with it, it just seemed like a natural svelte while on tour, away from there is some French blood on her side of the thing to do. -

Les Gremlins Et La RAF…

LES GREMLINS DANS LES ARMEES DE L'AIR Etude réalisée par Michel Coste ----- Depuis la nuit des temps, les peuples ont cru à l'existence d'êtres qui peuplaient leur imaginaire. Dénommés Elfes, Lutins, Trolls, Fées, Sylphes, Gnomes, tous sont nés de l'imagination populaire. Dès le Moyen-Age apparaissent les premières attestations de croyance envers ces créatures. À la Renaissance ces créations perdurent. Au XXeme siècle on continue d'y croire. On aurait pu penser de telles croyances en régression ou oubliées, dans ce monde moderne où le rationnel prime sur l’irrationnel. Les Gremlins et la RAF… Comment aurions-nous pu concevoir, qu'au sein de la RAF, l'imagination de ses membres les plus sensés ait pu donner naissance à l'existence d'un petit être espiègle parfois malveillant, ''le Gremlin'', et, de plus, accréditer son existence. La première notion de ''Gremlin'' (ce terme n'est pas encore employé) apparaît parmi les aviateurs au début du XXeme siècle. Le premier article se référant à ces êtres parut dans le journal ''The Spectator'' qui écrivait '' L'ancien Royal Naval Air Service en 1917 et la toute nouvelle Royal Air Force en 1918 apparaissent avoir détecté l'existence d'une horde d'Elfes mystérieux et malveillants dont le but entier était de …..'' Ainsi, dans cet écrit, était mis en exergue la cause (''les Gremlins'') et permettait de trouver une explication à des incidents inexplicables survenant en vol et se multipliant selon l'étrange loi des séries. Le 10 avril 1929 un poème, écrit par des aviateurs en service au Moyen Orient, paru à Malte dans le journal ''Aeroplane'' fait allusion aux Gremlins. -

Love These Films from the 2018 Providence Children's Film Festival?

Love these films from the 2018 Providence Children’s Film Festival? Check out related books recommended by Youth Services Staff at Providence Community Library: If you loved Abulele, try: Love Sugar Magic: A Dash of Trouble by Anna Meriano The Iron Giant by Ted Hughes The Witch Boy by Molly Knox Ostertag Hattie and Hudson by Chris Van Dusen A Monster Calls by Patrick Ness (12+ years old) If you loved Revolting Rhymes, try: Golem by David Wisniewski *Based on Roald Dahl’s Revolting Rhymes by Roald Dahl The True Story of the 3 Little Pigs by Jon Scieszka If you loved Bird Dog, try: Whatever After (series) by Sarah Mlynowski My Side of the Mountain by Jean Craighead George Dorothy Must Die (series) by Danielle Paige The Swiss Family Robinson by Johann Wyss A Tale Dark & Grimm (series) by Adam Gidwitz The School for Good and Evil by Soman Chainani If you loved Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, try: *Based on Chitty Chitty Bang Bang by Ian Fleming If you loved Room 213, try: Chitty Chitty Bang Bang Flies Again by Frank Cottrell Boyce LumberJanes by Noelle Stevenson; Grace Ellis; Shannon Watters; Kat The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster Leyh; Faith Erin Hicks Deep and Dark and Dangerous: A Ghost Story by Mary Downing Hahn If you loved, Hero Steps, try: GFFs: Ghost Friends Forever by Monica Gallagher; art by Kata Kane Emmanuel's Dream: The True Story of Emmanuel Ofosu Yeboah by Laurie Ann Thompson If you loved Step, try: Tangerine by Edward Bloor (12+ years old) Pieces of Why by K. -

Boggis and Bunce Love Food, So

Teacher’s Notes Pearson EnglishTeacher’s Kids Readers Notes Pearson English Kids Readers Level 4 Suitable for: young learners who have completed up to 200 hours of study in English Type of English: British Headwords: 800 Key words: 15 (see pages 2 and 7 of these Teacher’s Notes) Key grammar: irregular past simple verbs, relative pronouns, could for past ability and possibility, must for obligation Summary of the story drink from the farmers’ storehouses. Little do the Farmers Boggis, Bunce and Bean each have a farm. three farmers know all this as they sit outside, They are rich men, but mean. Mr Fox lives under a next to Mr Fox’s hole, waiting in vain for him to tree on a hill above the farms and feeds his family come out. with chickens from Boggis’s farm, ducks from Bunce’s farm and turkeys from Bean’s farm. Bean Background information also grows apples and makes cider from them. Roald Dahl’s popular story Fantastic Mr Fox was first published in 1970. A later edition included the The angry farmers are not happy that Mr Fox is illustrations by Quentin Blake that are also used in always taking their animals, and they decide to the Reader. kill the thief. They shoot at him when he leaves his hole one day, but they only take off his tail. So In 2009, the book was made into a film, with they decide to dig him out, first by hand and then the voices of George Clooney as Mr Fox and with diggers, but the foxes just dig deeper into the Meryl Streep as Mrs Fox. -

Heroes Hall Veterans Museum and Education Center

Heroes Hall Veterans Museum and Education Center Instructional Guide for Middle Schools OC Fair & Event Center 32nd District Agricultural Association State of California | Costa Mesa CA Heroes Hall Veterans Museum and Education Center: Instructional Guide for Middle Schools was developed by the OC Fair & Event Center. The publication was written by Beth Williams and designed by Lisa Lerma. It was published by the OC Fair & Event Center, 32nd District Agricultural Association, State of California, 88 Fair Drive, Costa Mesa, CA 92626. © 2018 OC Fair & Event Center. All rights reserved Reproduction of this document for resale, in whole or in part, is not authorized. For information about this instructional guide, or to schedule a classroom tour of Heroes Hall, please visit https://ocfair.com/heroes-hall/ or call (714) 708-1976. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Graphic Organizers for Visit 103 Pre-Visit Nonfiction Lessons 2 Heroes Hall Graphic Organizer (Blank) 104 Aerospace in California During World War II 3 Heroes Hall Exhibits Graphic Organizer 106 Attacks on the United States Mainland Heroes Hall: Soldiers and Veterans During World War II 7 Graphic Organizer 110 Santa Ana Army Air Base History 12 Post-Visit Activities 112 Joe DiMaggio: A Soldier 19 Writing Assignment: Informal Letter - Thank a Soldier/Thank a Veteran 113 “Gremlins” of World War II 23 Creative Writing Assignment: The Women Who Served 28 Informal Letter 115 Native American Code Talkers 33 Creative Writing Assignment: Formal Letter 117 Tuskegee Squadron Formation Essay -

The Top Five Films You Did Not Know Were Based on Roald Dahl Stories

The top five films you didn’t know were based on Roald Dahl stories Many Roald Dahl stories have been turned into family film favourites that we know and love, but did you know there’s more than just the books? Roald Dahl is responsible for a number of classic screenplays and storylines that we wouldn’t normally associate him with. Here’s five of our favourites, which you can enjoy once again on the big screen as part of Roald Dahl on Film: 1. Chitty Chitty Bang Bang Roald Dahl was responsible for the screenplay of this truly magical, musical film. In fact, it was Roald Dahl that added in the Child Catcher as an extra character – so he’s responsible for giving us all those nightmares when we were small! 2. 36 hours This war movie released in 1965 was based on the short story ‘Beware of the Dog’ by Roald Dahl, which was first published in Harper’s Magazine in 1946. The story was also said to have influenced television series, The Prisoner. 3. You Only Live Twice The screenplay of this James Bond classic was another of Roald Dahl’s after he was approached by James Bond producers, Harry Saltzman and Albert Broccoli. The screenplay was the first to stray from Ian Fleming’s original story, as Roald Dahl famously said that the original wasn’t Fleming’s best work. 4. Gremlins The 1984 Steven Spielberg film Gremlins features characters developed from one of Roald Dahl’s earliest books, The Gremlins. In fact, there’s every chance that it was Roald Dahl’s first ever book for children! It impressed his bosses at the British Embassy so much that they sent it to Walt Disney to make into a feature film. -

Book Talk Page 1

Last Kids on Earth Max Brallier The Last Kids on Earth Level 4.1 / 3 points The Zombie Parade Level 4.0 / 4 points The Nightmare King Level 4.3 / 4 points The Cosmic Beyond Level 3.9 / 4 points The Midnight Blade Level 4.3 / 4 points The Skeleton Road Level 4.4 / 5 points Last Kids on Earth Survival Guide June's Wild Flight Level 4.1 / 4 points Dog and Puppy series W. Bruce Cameron A Dog's Purpose Level 5.6 / 13 points A Dog's Journey Level 4.6 / 13 points A Dog's Promise Level 4.5 / 15 points Bella's Story Level 4.2 / 6 points Ellie's Story Level 4.2 / 6 points Bailey's Story Level 4.5 / 5 points Molly's Story Level 3.9 / 5 points Max's Story Level 4.4 / 5 points Toby's Story Level 4.0 / 5 points Lily's Story Level 4.2 / 5 points A Dog's Way Home Level 4.9 / 13 points Shelby's Story Level 4.3 / 5 points Lily to the Rescue Level 4.0 / 2 points Two Little Piggies Level 4.5 / 2 points The Not-So-Stinky Skunk Cooper’s Story (2021) Dog Dog Goose (2021) Lost Little Leopard (2021) The Misfit Donkey (2021) Foxes in a Fix (2021) The Three Bears (2021) A Dog's Courage (2021) February 2021 book talk Page 1 Hunger Games Suzanne Collins In a future North America, where rulers of Panem maintain control through an annual survival competition, 16-year-old Katniss's skills are tested when she voluntarily takes her sister's place. -

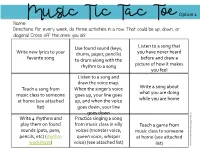

Week Activity — Music Tic Tac

Option 1 Use found sound (keys, Listen to a song that Write new lyrics to your drums, paper, pencils) you have never heard favorite song to drum along with the before and draw a rhythm to a song picture of how it makes you feel Listen to a song and draw the voice map. Teach a song from When the singer’s voice Write a song about music class to someone goes up, your line goes what you are doing at home (see attached up, and when the voice while you are home list) goes down, your line goes down Write 4 rhythms and Practice singing a song play them on found from music class in silly Teach a game from sounds (pots, pans, voices (monster voice, music class to someone pencils, etc) (rhythm queen voice, whisper at home (see attached worksheet) voice) (see attached list) list) Option 2 Watch a musical (a Play “The Young Compose your own movie with lots of Person’s Guide to the song at singing in it!) (see Orchestra” classicsforkids.com attached list) Learn about women Play “Isle of Tune” on a Download the Rhythm who composed music computer Cat app (for free!) to Listen to an episode practice your rhythms Do a worksheet Download the Watch some ukulele Pick some percussion Ningenius app (for free!) videos instruments and watch and try the rhythm (or watch these and play a Play-Along video (see game along with them!) attached instrument list) “Good Morning, Good Morning” “Buenos Dias, Como Estas?” “Snot” “Boa Constrictor” Music “Naughty Kitty Cat” Class “I Am A Pizza” (by Charlotte Diamond) Song “Little Bunny Foo Foo” List “Impossible to -

The Ten Scariest Roald Dahl Characters on Film

The ten scariest Roald Dahl characters on film Roald Dahl’s stories have delighted generations with their imagination and adventure. But every good story needs a baddie – and Roald Dahl’s were some of the scariest! Now fans of all ages can relive their fears as Roald Dahl’s films return, with 165 confirmed screenings and special events as part of the Roald Dahl on Film season. Here are ten characters that kept us up at night: 1. The Grand High Witch If the description in The Witches book wasn’t enough to give you nightmares, the image of Anjelica Huston as the Grand High Witch peeling off her mask to reveal her true face in the 1990 film adaptation was sure to do the trick. Huston spent eight hours in make-up before filming to transform into her character! 2. The Child Catcher Many aren’t aware, but the character of the Child Catcher in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang was added into Ian Fleming’s original story by Roald Dahl; a truly terrifying addition that still has us freaked out to this day. The role was played by Robert Helpmann, who used to take out his top set of false teeth during filming to make himself look more gaunt; this also created the hissed tones in his voice that used to fill our nightmares. 3. Miss Trunchbull We’re not sure what scares us more, being swung around the playground by our pigtails or enduring a spell in the ‘chokey’ for doing absolutely nothing wrong. Either way, we wouldn’t want to get on the wrong side of Matilda’s Miss Trunchbull! Watching Pam Ferris snort and charge like a bull in the 1996 film is enough to put any child off misbehaving; apparently she used to stay in character on set to scare all the children and make sure their fear was genuine when the camera was rolling! 4. -

Over to You: Ten Stories of Flyers and Flying PDF Book

OVER TO YOU: TEN STORIES OF FLYERS AND FLYING PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Roald Dahl | 160 pages | 28 Jan 2010 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780141189659 | English | London, United Kingdom Over to You: Ten Stories of Flyers and Flying PDF Book Also, I know women are supposedly preferred 'fat' as a show of class, Dahl even mentions it, but did this topic really need to be covered? What is it with Roald Dahl just killing animals every so often? Only This is the anxious wait of a mother for her son - a bomber crewman to come back from his raid. Price Mansfield, United Kingdom. I am thankful someone asked him to write this - it gave me a glimpse into his This early collection of Roald Dahl works was dark. Expedited UK Delivery Available. More information about this seller Contact this seller 5. All relating to pilots during war. Community Reviews. The book has been entirely dedicated to pilots engaged in the World War, their flying experiences, their ordeals, their pleasures and their spirits. Also another Roald Dahl short story collection will be in my bag shortly. The companionship, the exhilaration, the fear, the grief, the brutal reali Roald Dahl was a fighter pilot during WWII, flying missions over Africa and Greece, shooting down enough enemy planes to be considered an ace and once crashing so badly that he was temporarily blinded. In Africa he learnt to speak Swahili, drove from diamond mines to gold mines, and survived a bout of malaria where his temperature reached A Piece of Cake. Add to Basket Used Softcover. -

By Dr.Seuss) Brad Peterson, Publicity & Promotions Coordinator

Our Fav, ourite Childrens Books! To celebrate World Book Day 2018, we asked a few members of the Jolly Team about their favourite children’s books... Fantastic Mr Fox (by Roald Dahl) Jonathan Partington, Sales Director “Easy winner; Fantastic Mr Fox. I know you don’t need to know why as it is so obviously the best kids book ever written, by the best children’s author to have ever lived, illustrated (eventually) by a genius with coloured pens, but in case anyone has had the misfortune to miss the Fantastic Mr Fox... The book has it all, a hero, evil villains, teamwork and adventure. Mr Fox is as his name suggests, fantastic. He is the perfect hero, he has his faults but his daring, charm and skills shine through so he can save the day. Which, as luck would have it is exactly what he does. Having put his whole community at risk by being just a little too good at being a fox, he gets his gang together and leads them all to a famous, fantastic victory, while the baddies are left sitting out in the cold!” Oh, the Places Youll, Go! (by Dr.Seuss) Brad Peterson, Publicity & Promotions Coordinator “You have brains in your head, you have feet in your shoes. You can steer yourself in any direction you choose.” “I didn’t actually discover this book until I was an adult, but it’s easily my favourite. Aside from Dr. Seuss’ lyrical genius - entertaining yet incredibly easy to read - the message is really powerful, even for adults. -

'Fantastic Mr Fox' – Roald Dahl

Year 4 Home Learning w.c. 04.05.20 Topic ‘Fantastic Mr Fox’ – Roald Dahl Science: Living Things If you are able to read the book ‘Fantastic Mr. Fox’, we highly recommend it! There are lots of different animals in the book. Your science task is to Investigate which animals like to live underground and move around by digging. Which animals live above ground? Which animals only live in water? Can you sort these animals into groups? You can use the internet to research but also have a look in either the garden or the park if you are out for some exercise. DT: Puppets Can you make your own puppets of the characters in the story? You can use any resources you have at home. Watch this video which gives more information about the puppets in the film adaptation: https://youtu.be/Q5pQvytHIEE Art: Drawing Your challenge is to draw the seating arrangement for the feast scene. Which animals and family members came along? Where did they sit? PE: Dance Plan, choreograph and perform a dance for Mr Fox to perform when he arrives at Boggis's Chicken House Number One. Have a look on the Just Dance YouTube page for inspiration: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UChIjW4BWKLqpojTrS_tX0mg. There is a wide range of songs for you to dance to on the page. Topic: Geography Look on a local map to find the location of farms and woods in your area. Can you write a description of our local area? What kind of an area is it: rural or urban? How do you know this? English ‘Matilda’ – Roald Dahl This week, we will be focussing on the book ‘Matilda’.