Waste Recycling Investigative Committee Minutes 27/02/01

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SYD SOC NEWS 2010 Autumn

SYDENHAM SOCIETY NEWS Autumn 2010 SAVE SYDENHAM LIBRARY! Sydenham Library is under threat of closure following a proposal by Lewisham Council officers to close five of the Borough’s twelve libraries in an attempt to save £830,000. As well as Sydenham, New Cross, Crofton Park, Blackheath and Grove Park libraries also face the axe. The proposals were announced in early August and the Council is conducting a public consultation before mayor Sir Steve Bullock makes a decision on the issue on 17 November 17. Unsurprisingly, a vociferous campaign against the proposed The Save Sydenham Library Campaign has launched closure is under way. The Save Sydenham Library campaign an online and paper petition and is asking people to write was launched after a public consultation on 19 August. to the Mayor to show the depth of public feeling against the Campaigners point out that Sydenham Library is more than proposed closure. The issue has dominated the Sydenham and just Library; it is a much loved and well-used community asset Perry Vale Assemblies and that of Bellingham on 20 October, and hosts a number of activities apart from lending books. whose residents are also served the 106 year- old Library. As well as reading groups for seniors and people for whom In the relatively short space of time since the Save English is a second language, it is also used by four local Sydenham Library campaign was launched it has gathered primary schools, which will not be able to avail themselves of momentum and garnered widespread support. The people of alternative libraries in Forest Hill or Lewisham. -

Lewisham May 2018

Traffic noise maps of public parks in Lewisham May 2018 This document shows traffic noise maps for parks in the borough. The noise maps are taken from http://www.extrium.co.uk/noiseviewer.html. Occasionally, google earth or google map images are included to help the reader identify where the park is located. Similar documents are available for all London Boroughs. These were created as part of research into the impact of traffic noise in London’s parks. They should be read in conjunction with the main report and data analysis which are available at http://www.cprelondon.org.uk/resources/item/2390-noiseinparks. The key to the traffic noise maps is shown here to the right. Orange denotes noise of 55 decibels (dB). Louder noises are denoted by reds and blues with dark blue showing the loudest. Where the maps appear with no colour and are just grey, this means there is no traffic noise of 55dB or above. London Borough of Lewisham 1 1. Pepys Park 2. Deptford park 3. Sayes Court Park 2 4. Folkestone Gardens 5. Bridgehouse Meadows 6. Evelyn Green 3 7. Foredham Park 8. Margaret McMillan Park 9. Sue Godfrey Local Nature Reserve, St Paul’s Church Yard 4 10. Telegraph Hill Park (Upper, Lower) 11. Friendly Gardens 12. Broadway Fields, Brookmill Park 5 13. Hilly Fields Park 14. Ladywell Fields 15. Lewisham Park 6 16. Manor Park 17. Manor House Gardens 18. Mountsfield Park 7 19. Northbrook Park 20. Forster Memorial Park 21. Downham Playing Fields, Shaftesbury Park 8 22. Downham Fields 23. -

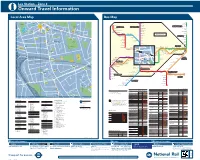

Local Area Map Bus Map

Lee Station – Zone 3 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map 200 War 2 Café 1 Old Tennis WEIGALL ROAD D Courts Memorial 15 A Tigers R O B15 E A D 315 P M Ichthus LEE GREEN Head E A D Blackheath M 394 M O W 202 L A A R S Playground BRIDGE 1 I L L Bexleyheath Christian 167 M D Royal Standard ST. PETERS CT Fellowship 2 Sozo Community A Shopping Centre Lee Green O R Manor House 418 Outreach Centre Sports Ground Fire Station E Leee GreenGreen L Gardens B 14 Sports Ground A R Lee Bible D M I E 116 G L 15 Y A Study Centre H Quaggy River T N Vanbrugh Park N Lewisham Tesco T 273 H N Bexleyheath O F U R I A 5 S E 2 Sainsbury’s M R AV E N S W Beaconsfield Road L L ANE BRIGHTFIELD ROAD AY 32 D 7 Blackheath Wanderers BEXLEYHEATH R R COURTLANDS AVENUE O O 72 W S Sports Club BLACKHEATH A M E D E Y A L HAMLEA CLOSE LEWISHAM D G D H E R AV E N S WAY 35 5 Lewisham Dorcis Avenue 59 The Leegate Prince Charles Road Shopping Centre Maze Hill R AV E N S WAY 35 Hail & Ride TAUNTON ROAD Footbridge HEDGLEY STREET 18 1 R AV E N S WAY 4 section FALMOUTH CLOSE Lewisham Leybridge 1 62 Clock Tower for Lewisham Centre r St. Peter’s Prince Charles Road e 34 LEYLAND ROAD Riverston 15 62 v Manor House FA Holmesdale Road i A D Estate Church I R B Y R Playing Fields Clarendon Hotel R Trinity R O School O A D Gardens N y C of E T O g U N 50 261 Lee High Road g TA a School 54 T u R Belmont Hill 20 U Q Abbey Manor College O ELTHAM ROAD C 137 15 Elsa Road E Lee High Road Blackheath Village CHALCROFT ROAD Footbridge 29 Broadoak Campus D G The yellow tinted area includes every 127 I BURNT ASH ROAD B R Lee High Road 53 Y R E E D C L O S E Belmont Park Royal Parade M 37 E OODVILLE 23 L W SE 20 WANTAGE ROAD CLO S O U T H B O U R N E G A R D E N S Brandram Road bus stop up to one-and-a-half miles 1 CAMBRIDGE DRIVE A A D 23 173 COURTLANDS AVENUE R O 43 1 from Lee Station and Horn Park. -

The Anchor and the Stitch

THE ANCHOR AND THE STITCH MSc Building and Urban Design in Development TRANSOFRMING LOCAL AREAS: TERM 2: URBAN INTERVENTION REPORT Tutor: Hannah R. Visser, Jonah Rudlin, Hazem Raad, Kaixin Lin, Yijin Wang, Lanqing Hou 1 CONTENTS Executive summary 4 List of figures 5 INTRODUCTION 6 CONTEXT + METHODOLOGY 8 URBAN ANALYSIS 10 VISION 14 AN ACTION PLAN 17 INTERVENTION 1: THE STITCH 18 INTERVENTION II: THE ANCHOR 24 CONCLUSION 32 BIBLIOGRAPHY 34 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY LIST OF FIGURES his design report is the result of a research project carried out in Lewisham, London during the Figure 1 Lee in London Context 6 second term. The work derives from an urban analysis, of which the purpose was exploring urban Figure 2 Urban Design Process: Carmona’s Place-Shaping Continuum. 7 landmarks and Lee’s urban fabric. T Source: Allison Anderson, Lisa Law, Journal of Urban Design 2015, 20, 545-562 It postulates a critical design intervention on the basis of a thorough investigation of Lewisham’s municipal and Figure 3 Sense of Place. 9 more local dynamics; the economic and cultural forces Lee is subjected to; and above all, the spatial powers raging through the outer zones of an increasingly unaffordable global city. The report provides a schematic Source: Carmona, M., Tiesdell, S., Heath, T., and Oc, T., 2003. P.122 reflection upon the potentialities and points of improvements of Lee. Doing so, different lenses and various Figure 4 Synthesis of 6 Lens in the Four Dimensional Contex 9 scales have been deployed in order to reach a vision. Figure 5 SWOT Framework 11 In formulating a design response we have strived to uphold a creative attitude, at all times respecting that Figure 6 Mental Map and Key Intervention 13 knowledge about urban interventions is not only professional. -

Parks Management Review’

Parks management scrutiny review – parks visit - 8 August 2019 Overview On Thursday 8 August Councillors from the Sustainable Development Select Committee carried out a visit to gather evidence for the Committee’s ‘Parks management in-depth review’. Attendees Councillor Patrick Codd Councillor Mark Ingleby (until noon) Councillor Louise Krupski Timothy Andrew (Scrutiny Manager) Vince Buchanan (Service Group Manager, Green Scene) Nick Pond (Ecological Regeneration and Open Space Policy Manager) Nigel Tyrell (Director of Environment) (until noon) Locations visited Manor House Gardens Hither Green Crematorium Blackheath Deptford Park/Deptford Park Community Orchard Brookmill nature reserve Luxmore Gardens Questions arising from the Committee’s key lines of enquiry At its meeting in June 2019 the Committee discussed a scoping report for a ‘parks management review’. The Committee agreed a number of ‘key lines of enquiry’ to focus its evidence gathering. Principally, as regards parks management the Committee seeks to understand: What good practice should Lewisham seek to retain and which areas could be strengthened further? Further to the agreement of the scope of the review (and in advance of the visit) the Committee a discussed key issues it wished to raise about the management of parks. Members on the visit also put forward suggestions for key questions, as follows: What are the differences between management of big/small parks/pocket parks? How businesses/cafes are managed in parks? Is there a process for creating links/routes/signage -

Lockdown Flyer

Lewisham Community Toilets Map Open during Tier 3 & 4 Disabled Access BELLINGHAM 5 1. Forster Park Whitefoot Ln BR1 5SQ Baby Change 6DEPTFORD Mon-Sun: 10am-4pm Gender Neutral NEW CROSS 21 BROCKLEY & CROFTON PARK 20 2. Café Cro1on Park 397 Brockley Rd TELEGRAPH SE4 2PH Mon-Sat: 7am-4pm 24 HILL 3. Hilly Fields Park Adelaide Av SE14 1LE 19 BLACKHEATH Mon-Sun: 9am-4pm BROCKLEY LEWISHAM CENTRE CATFORD CROFTON 4. Tesco Ca<ord 16-21 Winsdale Way SE6 PARK 3 14 17 4JU Mon-Fri: 7am-8pm| Sat: 7am-7pm | 16 LEE 18 LADYWELL Sun: 10am-4pm 2 HITHER 13 GREEN 15 HONOR 4 DEPTFORD OAK 5. Dep<ord Park Evelyn St SE8 5DD Mon-Sun: 11am-5pm 9 CATFORD 6. Festa Sul Prato 222 FOREST HILL Trundleys Rd SE8 5JE GROVE PARK12 BELLINGHAM Mon-Fri: 6am-10pm | SYDENHAM 1 11 Sat-Sun: 7am-6pm 23 22 DOWNHAM 10 w Le i 7 o in sh DOWNHAM 8 o a L m e 7. Beckenham Place Park Stable Lodge h g t Beckenham Hill Rd BR3 1SY n i t t Mon-Sun: 9.30am-4pm u P 8. Café Treat 461 Bromley Rd BR1 4PH Mon-Sat: 8am-7pm | Sun: 9am-5pm LEE 17. Manor House Gardens 34 Old Rd SE13 5SY FOREST HILL & HONOR OAK Mon-Sun: 9am-4pm 9. Sainsbury’s Forest Hill 34-48 London Rd SE23 18. Sainsbury’s Lee 14 Burnt Ash Rd SE12 8PZ 3HF Mon-Sat: 7am-10pm | Sun: 12pm-6pm Mon-Sat: 7am-10pm | Sun: 11am-5pm LEWISHAM GROVE PARK 19. -

Green Spirit -Glendale's Spring 2011 Newsletter.Pub

Issue 5 The Previous 10-Year Partnership by Molly Hingston Summer 2011 Glendale’s partnership with the London Borough of Lewisham has attracted national recognition for putting parks and open spaces at the heart of local communities. A unique combination of proven green expertise, investment, innovation and accountability successfully met the challenge to revitalise Lewisham’s green spaces. The following highlights some of the achievements and successes of the previous 10-year partnership; 2000 In the year 2000, the partnership between the Borough of Lewisham and Glendale began by a unique private finance initiative investment scheme. Over a three-year period Lewisham received a £1.5m investment from Glendale to finance improvements to parks and green spaces. One of the projects included a £340,000 investment at Chinbrook Meadows to develop the sports pavilion, playground and cricket pitch. 2001 The following year, 2001, Lewisham was awarded the ‘London in Bloom’ award for the ‘Most improved Borough’. The first ever catering facility in the parks opened at Manor House Gardens. Investments were also made in other parks across the Borough; from footpaths to fencing, park signs to toilets and bridges ‘Pistachios in the Park ‘at Manor House Gardens to paddling pools. 2002 A section of the River Quaggy was returned to its natural state in 2002 as part of a £1.2m regeneration project of Chinbrook Meadows. The scheme was the culmination of an innovative partnership between Groundwork, London Borough of Lewisham, Environment Agency and Glendale. A bedding memorial was created in Deptford Park to celebrate the Queen’s Jubilee. 2003 2003 saw the first Lewisham Walking Festival and the first Farmers’ Market which was held in Manor House Gardens. -

Note Book on the Parks, Gardens, Recreation Grounds, and Open

ou c i f Jonbon gour d! g n . —0 N O T E BO O K O N T H E PARK GARDEN S, S, RECREATION AND OPEN SPACE GROUNDS, S D N OF LON O . under the direction o L ieutmnt-C olonel S aab f y, C hief Oficor of the P arks D epartment . JA N U A R Y , 1 902. !T HI R D E mu ox .) m“. and S on Print ers S ufiolk Lane Jan. T ra , , , P R E F A C E . T h e P arks C ommittee h aving considered it desirable to pro vide in a c onci se formfor t h e info rmation of mm rs nd art ic ulars of , e be a oth ers, p t h e various ar s ardens recreation rounds and t h er o en s ac es p k , g , g , o p p under t h eir control a eneral d s ri ti n is h i v of h of suc h , g e c p o ere g en eac l l d p ac es. I t h as a so been eemed desirable to devot e spec ial ch apters t o t h e following subjcots Hoc key 58 Hurli ng 58 Lac rosse 58 Lawn-tennis 58 Q uoits 59 By-laws S h int y 59 i l S atin 59 C h aracterist cs, genera k g C it y C o rporation parks T ambourello 60 L d Pon 5 1 C onvenienc es . -

Conservation Management Plans Relating to Historic Designed Landscapes, September 2016

Conservation Management Plans relating to Historic Designed Landscapes, September 2016 Site name Site location County Country Historic Author Date Title Status Commissioned by Purpose Reference England Register Grade Abberley Hall Worcestershire England II Askew Nelson 2013, May Abberley Hall Parkland Plan Final Higher Level Stewardship (Awaiting details) Abbey Gardens and Bury St Edmunds Suffolk England II St Edmundsbury 2009, Abbey Gardens St Edmundsbury BC Ongoing maintenance Available on the St Edmundsbury Borough Council Precincts Borough Council December Management Plan website: http://www.stedmundsbury.gov.uk/leisure- and-tourism/parks/abbey-gardens/ Abbey Park, Leicester Leicester Leicestershire England II Historic Land 1996 Abbey Park Landscape Leicester CC (Awaiting details) Management Management Plan Abbotsbury Dorset England I Poore, Andy 1996 Abbotsbury Heritage Inheritance tax exempt estate management plan Natural England, Management Plan [email protected] (SWS HMRC - Shared Workspace Restricted Access (scan/pdf) Abbotsford Estate, Melrose Fife Scotland On Peter McGowan 2010 Scottish Borders Council Available as pdf from Peter McGowan Associates Melrose Inventor Associates y of Gardens and Designed Scott’s Paths – Sir Walter Landscap Scott’s Abbotsford Estate, es in strategy for assess and Scotland interpretation Aberdare Park Rhondda Cynon Taff Wales (Awaiting details) 1997 Restoration Plan (Awaiting Rhondda Cynon Taff CBorough Council (Awaiting details) details) Aberdare Park Rhondda Cynon Taff -

Lee Manor Conservation Area Character Appraisal

Lee Manor conservation area character appraisal Lee Manor conservation area Summary of Special Interest Lee Manor represents a planned suburb built in the late 19th and early 20th centuries on land owned by the Baring Family. The northern part of the conservation area includes the old main road from Lewisham to Eltham with the 17th and 18th century buildings of Pentland Place and The Manor, which was built in 1772 and later bought by the Baring family. It is now a public library and the surroundings a well maintained and attractive public park. The Old Road was bypassed in the early 19th century by a more northerly route and is now a quiet, leafy backstreet. The opening of Lee Railway Station in 1856 provided an impetus for development of suburban housing for city workers. Early planned housing is located in the north east and comprises terraces of small artisan dwellings. Slightly later areas of small, medium and large town houses are located in the south. These were built within planned streets on a grid pattern, in regularly sized plots. Their construction in batches created groups, which posses repeated scale, form, style and motifs. A number of public buildings, including a church and a school building were included in the planned layout along with small rows of shops and a public house, giving the area the sense of a self-contained community. The buildings have retained original features, including decorative mouldings, traditional timber framed windows, suspended porches and tiled garden paths. Despite variations in style there is also highly consistent use of materials, with a number of areas standing out as a result of uniformalised use of alternatives. -

Draft Lewisham Parks and Open Space Strategy 2020-2025

“To be the heart and lungs for Lewisham, connecting active, healthy and vibrant local communities” Parks and Open Spaces Strategy 2020-2025 QUOTES 2 Introduction & forward by Councillor Sophie McGeevor, Cabinet Member for Environment and Transport Our Baseline This Parks and Open Space strategy has been developed as tool to identify, communicate, map out and monitor a 47 Parks, 18 Nature Reserves, 6 course of actions to reflect the shared vision: “to be the heart and lungs for Lewisham, connecting active, healthy, designated Local Nature Reserves, 5 and vibrant local communities.” Churchyards, 37 Allotments The network, number, size and quality of parks and open spaces provides an essential ecosystem service that help 15 Green Flag Parks and 3 protect and regulate our immediate environment. Community Green Flag Award Spaces They give clean air, regulate temperature and provide flood storage. They are an important home for wildlife and biodiversity, and have direct social value providing health and wellbeing for local residents. They do this by 1st Place “Good Parks for London” encouraging recreational opportunities and supporting active lifestyles. benchmarking in 2017, 2018 & 3rd in 2019 They can connect and shape an area and improve the visual attractiveness of where we live and work. Our parks and open spaces define the character of our neighbourhoods and their unique identity. They improve the Support 25 formalised park user economic performance of the borough by supporting town centres, retaining employment, attracting new ‘Friends’ groups businesses and skills, and by increasing the value of domestic and commercial properties. The benefit from this green infrastructure has been calculated to a value of up to £2.1 billion. -

Guide £375,000 - £385,000

HITHER GREEN LANE, HITHER GREEN, LONDON SE13 6TS GARDEN FLAT FOR SALE GUIDE £375,000 - £385,000. www.markbeaumont.com [email protected] 020 8852 5000 Property Summary AVAILABLE NOW. VACANT POSESSION. Garden flat. Share of Freehold. Off Street Parking. Two Bedrooms. Beautiful Building. No chain. Available now. Buy in time to beat the stamp duty deadline. We hold keys to show you around. Property Features PRIVATE GARDEN SHARE OF FREEHOLD 2 BEDROOMS GROUND FLOOR FLAT CELLAR NO CHAIN BUY BEFORE STAMP DUTY HOLIDAY ENDS OFF STREET PARKING GOOD CONDITON 0.4 MILE HITHER GREEN STATION DESCRIPTION Garden flat. Share of Freehold. Off Street Parking. Two Bedrooms. As vendors sole agent we are pleased to be selling this ground floor garden flat. This property has direct access to a private rear garden of 30' x 19'. Located in Hither Green just 0.4 mile from Hither Green Station. Inside there is a decent sized living room, two bedrooms and a modern kitchen and modern bathroom. There is a cellar for storage too. This flat is vacant and ready to move into which you could do if you are quick before the end of the stamp duty holiday. We hold keys to show you around immediately. #AskBeaumont #Since 1999. COMMUNAL ENTRANCE ENTRANCE HALL CELLAR 15' 9" x 5' 6" (4.8m x 1.68m) LIVING ROOM 14' 5" x 11' 0" (4.39m x 3.35m) KITCHEN 9' 7" x 6' 10" (2.92m x 2.08m ) BEDROOM ONE 12' 2" x 11' 2" (3.71m x 3.4m) BEDROOM TWO 10' 7" x 9' 1" (3.23m x 2.77m ) PRIVATE GARDEN 30' x 18' 11" (9.14m x 5.77m) OFF STREET PARKING DISTANCES Distances are taken from googlemaps.co.uk.