The Form, Function and Evolution of Irregular Field Systems in Suffolk, C.1300 to C.1550*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baptism Data Available

Suffolk Baptisms - July 2014 Data Available Baptism Register Deanery or Grouping From To Acton, All Saints Sudbury 1754 1900 Akenham, St Mary Claydon 1754 1903 Aldeburgh, St Peter & St Paul Orford 1813 1904 Alderton, St Andrew Wilford 1754 1902 Aldham, St Mary Sudbury 1754 1902 Aldringham cum Thorpe, St Andrew Dunwich 1813 1900 Alpheton, St Peter & St Paul Sudbury 1754 1901 Alpheton, St Peter & St Paul (BTs) Sudbury 1780 1792 Ampton, St Peter Thedwastre 1754 1903 Ashbocking, All Saints Bosmere 1754 1900 Ashby, St Mary Lothingland 1813 1900 Ashfield cum Thorpe, St Mary Claydon 1754 1901 Great Ashfield, All Saints Blackbourn 1765 1901 Aspall, St Mary of Grace Hartismere 1754 1900 Assington, St Edmund Sudbury 1754 1900 Athelington, St Peter Hoxne 1754 1904 Bacton, St Mary Hartismere 1754 1901 Badingham, St John the Baptist Hoxne 1813 1900 Badley, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1902 Badwell Ash, St Mary Blackbourn 1754 1900 Bardwell, St Peter & St Paul Blackbourn 1754 1901 Barham, St Mary Claydon 1754 1901 Barking, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1900 Barnardiston, All Saints Clare 1754 1899 Barnham, St Gregory Blackbourn 1754 1812 Barningham, St Andrew Blackbourn 1754 1901 Barrow, All Saints Thingoe 1754 1900 Barsham, Holy Trinity Wangford 1813 1900 Great Barton, Holy Innocents Thedwastre 1754 1901 Barton Mills, St Mary Fordham 1754 1812 Battisford, St Mary Bosmere 1754 1899 Bawdsey, St Mary the Virgin Wilford 1754 1902 Baylham, St Peter Bosmere 1754 1900 09 July 2014 Copyright © Suffolk Family History Society 2014 Page 1 of 12 Baptism Register Deanery or Grouping -

Responses to Bredfield Neighbourhood Plan

Responses to Bredfield Neighbourhood Plan Further Consultation Publicity period: 22 May to 12 June 2020 Responses to Bredfield Neighbourhood Plan | Further Consultation | Responses Anglian Water ....................................................................................................... 1 B K Cook ............................................................................................................... 2 Clive Coles ............................................................................................................ 4 Environment Agency ............................................................................................. 6 G Gamble and S Manville ...................................................................................... 7 L Marriott ............................................................................................................ 10 M and D Lewis ..................................................................................................... 13 National Grid ....................................................................................................... 15 Natural England ................................................................................................... 18 Suffolk County Council ......................................................................................... 19 Responses to Bredfield Neighbourhood Plan | Further Consultation | What is the purpose of this document? Bredfield Parish Council submitted their Neighbourhood Plan to East Suffolk Council -

Classes and Activities in the Mid Suffolk Area

Classes and activities in the Mid Suffolk area Specific Activities for Cardiac Clients Cardiac Exercise 4 - 6 Professional cardiac and exercise support set up by ex-cardiac patients. Mixture of aerobics, chair exercises and circuits. Education and social. Families and carers welcome. Mid Suffolk Leisure Centre, Stowmarket, IP14 1LH on Monday 2-3pm, Wednesday 2.30pm-3.30pm and Friday 10.45 – 11.45am. Bob Halls 01449 674980 or 07754 522233 Red House (Old Library), Stowmarket, IP14 1BE on Friday 1.30-2.30pm. Maureen Cooling 01787 211822 3 27/02/2017 General Activities Suitable for all Clients Aqua Fit 4-6 A fun and invigorating all over body workout in the water designed to effectively burn calories with minimal impact on the body. Great for those who are new or returning to exercise. Mid Suffolk Leisure Centre, Stowmarket, IP14 1LH on Monday 2-3pm (50+), Tuesday 1-2pm and Thursday 9.10 - 9.55pm. Becky Cruickshank 01449 674980 Stradbroke Leisure Centre, IP21 5JN on Monday 12pm-12.45pm, Tuesday 1.45- 2.30pm, Thursday 11- 11.45 and 6.30-7.30pm. Stuart Murdy 01379384376. Balance Class 3 Help with posture and stability. Red Gables Community Centre, Stowmarket, IP14 1BE on Mondays (1st, 2nd and 4th) at 10.15-11am. Lindsay Bennett 01473 345350 Body Balance 4-6 BODYBALANCE™ is the Yoga, Tai Chi, Pilates workout that builds flexibility and strength and leaves you feeling centred and calm. Controlled breathing, concentration and a carefully structured series of stretches, moves and poses to music create a holistic workout that brings the body into a state of harmony and balance. -

Suffolk Coastal Local Plan

East Suffolk Council – Suffolk Coastal Local Plan Addendum to the Sustainability Appraisal Report Proposed Main Modifications to the Local Plan April 2020 East Suffolk Council – Suffolk Coastal Local Plan Main Modifications to the Local Plan Sustainability Appraisal Addendum April 2020 Contents Non Technical Summary ............................................................................................................ 2 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 5 2. Assessment of Main Modifications ...................................................................................... 10 3. Updates to Sustainability Appraisal Report ....................................................................... 357 4. Conclusion .......................................................................................................................... 423 Page 1 East Suffolk Council – Suffolk Coastal Local Plan Main Modifications to the Local Plan Sustainability Appraisal Addendum April 2020 Non-Technical Summary Sustainability Appraisal (SA) is an iterative process which must be carried out during the preparation of a Local Plan. Its purpose is to promote sustainable development by assessing the extent to which the emerging plan, when considered against alternatives, will help to achieve relevant environmental, economic and social objectives. Section 19 of the Planning and Compulsory Purchase Act 2004 requires a local planning authority to carry -

'From India to Ireland', Marx on the Agrarian Commune: the Internal Dynamics of the Irish Rundale Commune

9 200 The Ecological Dynamics of the September Rundale Agrarian Commune – 51 Eamonn Slater Eoin Flaherty No NIRSA Working Paper Series The Ecological Dynamics of the Rundale Agrarian Commune. Eamonn Slater and Eoin Flaherty∗ Department of Sociology and NIRSA ABSTRACT: In the following account we apply a Marxist ‘mode of production’ framework that attempts to create a better understanding of the complex relationships between society and nature. Most of the discussion of the dualism of nature/society has tended to replicate this divide as reflected in the intellectual division between the natural sciences and the social sciences. We hope to cross this analytic divide and provide an analysis that incorporates both natural and social variables. Marx’s work on ecology and ‘mode of production’ provides us with the theoretical framework for our examination into the essential structures of the Irish rundale agrarian commune. His analysis of modes of production includes not only social relations (people to people) but also relations of material appropriation (people to nature) and therefore allows us to combine the social forces of production with the natural forces of production. The latter relations are conceptualized by Marx as mediated through the process of metabolism, which refers to the material and social exchange between human beings and nature and vice-a-versa. However, what is crucial to Marx is how the natural process of metabolism is embedded in its social form – its particular mode of production. Marx suggested that this unity of the social and the natural was to be located within the labour process of the particular mode of production and he expressed this crucial idea in the concept of socio-ecological metabolism. -

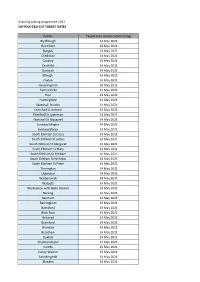

Grass Cutting 2021 Target Dates (SCC Website).Xlsx

Grassing cutting programme 2021 SUFFOLK C&U CUT TARGET DATES Parish: Target date (week commencing) Blythburgh 24 May 2021 Bramfield 24 May 2021 Bungay 24 May 2021 Chediston 24 May 2021 Cookley 24 May 2021 Cratfield 24 May 2021 Dunwich 24 May 2021 Ellough 24 May 2021 Flixton 24 May 2021 Heveningham 24 May 2021 Homersfield 24 May 2021 Hoo 24 May 2021 Huntingfield 24 May 2021 Ilketshall St John 24 May 2021 Ilketshall St Andrew 24 May 2021 Ilketshall St Lawrence 24 May 2021 Ilketshall St Margaret 24 May 2021 Linstead Magna 24 May 2021 Linstead Parva 24 May 2021 South Elmham St Cross 24 May 2021 South Elmham St James 24 May 2021 South Elmham St Margaret 24 May 2021 South Elmham St Mary 24 May 2021 South Elmham St Michael 24 May 2021 South Elmham St Nicholas 24 May 2021 South Elmham St Peter 24 May 2021 Thorington 24 May 2021 Ubbeston 24 May 2021 Walberswick 24 May 2021 Walpole 24 May 2021 Wenhaston with Mells Hamlet 24 May 2021 Barking 24 May 2021 Barnham 24 May 2021 Barningham 24 May 2021 Battisford 24 May 2021 Beck Row 24 May 2021 Belstead 24 May 2021 Bramford 24 May 2021 Brandon 24 May 2021 Brantham 24 May 2021 Buxhall 24 May 2021 Chelmondiston 24 May 2021 Combs 24 May 2021 Coney Weston 24 May 2021 East Bergholt 24 May 2021 Elveden 24 May 2021 Eriswell 24 May 2021 Erwarton 24 May 2021 Euston 24 May 2021 Fakenham Magna 24 May 2021 Flowton 24 May 2021 Freston 24 May 2021 Great Blakenham 24 May 2021 Great Bricett 24 May 2021 Great Finborough 24 May 2021 Harkstead 24 May 2021 Harleston 24 May 2021 Holbrook 24 May 2021 Honington 24 May 2021 Hopton -

St Lawrence's, Brundish & St Mary's, Wilby Parish

St Lawrence’s, Brundish & St Mary’s, Wilby February 2018 March 2018 Parish Magazine Facebook ‘Brunby and friends’ Supported by community donations and advertising revenue LOCAL DIRECTORY RECTOR Rev’d David Burrel 01986 798136 PRIEST Rev’d Ron Orams 01986 798901 OIL SYNDICATE Tim Gillingham 01728 628752 OIL Rix Petroleum 0800 5424924 CINEMA Priscilla Williamson 01379 388034 BRUNDISH HALL HIRE David Holliday 07765 345541 WILBY HALL HIRE Ian Taylor 01379 388112 POLICE Community 01986 385300 BROADBAND Fram Broadband 01728 726507 DEFIBRILLATOR (BRUNDISH) Peter Palmer 01728 628696 DEFIBRILLATOR (WILBY) VETS 01379 844704 DOCTOR Framlingham 01728 726507 DOCTOR Fressingfield 01728 586227 DENTIST Framlingham Dental 01728 723651 VET Framlingham 01728 621666 VET Castle Framlingham 01728 723481 GYM & SWIM Stradbroke Fitness 01379 384376 PRE-SCHOOL Occold 01379 678397 SCHOOL Wilby Primary School 01379 384708 SCHOOL Thomas Mills 01728 723493 SCHOOL Stradbroke 01379 384387 LIBRARY Framlingham 01728 723735 MILK DELIVERY Milk & More 01493 660400 PUB The Crown 01728 628282 TAXI Country Cars 01728 724377 TAXI Warnes 01728 724160 BUS LINK Connecting Communities 01449 614271 LETTER FROM THE EDITOR Dear Reader, Facebook page, ‘Brunby and friends’. We now have over 41 members, it is for all residents in Wilby and Brundish and everyone is welcome. You can remind us of events, update news and information, put photos up (old and new!) and share in your community. There is lots to read about in the magazine. We would like to hear from you for new ideas for the magazine. Our aim is to increase our readership and involve more people. We deliver to about 235 houses and would like to provide something for everyone! Happy New Year! We wish you all the best for 2018. -

1 Neolithic Population Crash in Northwest Europe Associated With

Neolithic population crash in northwest Europe associated with agricultural crisis Sue Colledge1*, James Conolly2, Enrico Crema3 and Stephen Shennan1 [email protected]; [email protected]; Institute of Archaeology, University College London, London WC1H 0PY, UK [email protected]; Department of Anthropology, Trent University, Peterborough, Ontario K9J 7B8, Canada 3 [email protected]; McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 3ER, UK *corresponding author: [email protected]; +44 (0)20 7679 4771 Abstract The focus of this paper is the Neolithic of northwest Europe, where a rapid growth in population between ~5950 and ~5550 cal yr BP, is followed by a decline that lasted until ~4950 cal yr BP. The timing of the increase in population density correlates with the local appearance of farming and is attributed to the advantageous effects of agriculture. However, the subsequent population decline has yet to be satisfactorily explained. One possible explanation is the reduction in yields in Neolithic cereal-based agriculture due to worsening climatic conditions. The suggestion of a correlation between Neolithic climate deterioration, agricultural productivity and a decrease in population requires testing for northwestern Europe. Data for our analyses were collected during the Cultural Evolution of Neolithic Europe project. We assess the correlation between agricultural productivity and population densities in the Neolithic of northwest Europe by examining the changing frequencies of crop and weed taxa before, during and after the population ‘boom and bust’. We show that the period of population decline is coincidental with a decrease in cereal production linked to a shift towards less fertile soils. -

Notice of Poll and Situation of Polling Stations

NOTICE OF POLL AND SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS Suffolk County Council Election of a County Councillor for the Bosmere Division Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of a County Councillor for Bosmere will be held on Thursday 4 May 2017, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. The number of County Councillors to be elected is one. 3. The names, home addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for election and the names of all persons signing the Candidates nomination paper are as follows: Names of Signatories Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Assentors CARTER Danescroft, Ipswich The Green Party Thomas W F Coomber Amy J L Coomber (++) Terence S Road, Needham (+) Ruth Coomber Market, Ipswich, Gregory D E Coomber Dorothy B Granville Suffolk, IP6 8EG Bistra C Carter Geoffrey M Turner Judith C Turner John E Matthissen Nicola B Gouldsmith ELLIOTT 3 Old Rectory Close, Labour Party William J Marsburg (+) Hayley J Marsburg (++) Tony Barham, IP6 0PY Brenda Smith William E Smith Gladys M Hiskey Clive I Hiskey Frances J Brace Kester T Hawkins Emma L Evans Paul J Marsburg PHILLIPS 46 Crowley Road, Liberal Democrat Wendy Marchant (+) Michael G Norris (++) Steve Needham Market, David J Poulson Graham T Berry IP6 8BJ Margaret A Phillips Lynn Gayle Anna L Salisbury Robert A Luff Peggy E Mayhew Peter Thorpe WHYBROW The Old Rectory, The Conservative Party Claire E Welham (+) Roger E Walker (++) Anne Elizabeth Jane Stowmarket Road, Candidate John M Stratton Carole J Stratton Ringshall, Stowmarket, Michael J Brega Claire V Walker Suffolk, IP14 2HZ Julia B Stephens-Row David E Stephens-Row Stuart J Groves David S Whybrow 4. -

The Long Island Historical Journal

THE LONG ISLAND HISTORICAL JOURNAL United States Army Barracks at Camp Upton, Yaphank, New York c. 1917 Fall 2003/ Spring 2004 Volume 16, Nos. 1-2 Starting from fish-shape Paumanok where I was born… Walt Whitman Fall 2003/ Spring 2004 Volume 16, Numbers 1-2 Published by the Department of History and The Center for Regional Policy Studies Stony Brook University Copyright 2004 by the Long Island Historical Journal ISSN 0898-7084 All rights reserved Articles appearing in this journal are abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life The editors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Office of the Provost and of the Dean of Social and Behavioral Science, Stony Brook University (SBU). We thank the Center for Excellence and Innovation in Education, SBU, and the Long Island Studies Council for their generous assistance. We appreciate the unstinting cooperation of Ned C. Landsman, Chair, Department of History, SBU, and of past chairpersons Gary J. Marker, Wilbur R. Miller, and Joel T. Rosenthal. The work and support of Ms. Susan Grumet of the SBU History Department has been indispensable. Beginning this year the Center for Regional Policy Studies at SBU became co-publisher of the Long Island Historical Journal. Continued publication would not have been possible without this support. The editors thank Dr. Lee E. Koppelman, Executive Director, and Ms. Edy Jones, Ms. Jennifer Jones, and Ms. Melissa Jones, of the Center’s staff. Special thanks to former editor Marsha Hamilton for the continuous help and guidance she has provided to the new editor. The Long Island Historical Journal is published annually in the spring. -

MAP BOOKLET Site Allocations and Area Specific Policies

MAP BOOKLET to accompany Issues and Options consultation on Site Allocations and Area Specific Policies Local Plan Document Consultation Period 15th December 2014 - 27th February 2015 Suffolk Coastal…where quality of life counts Woodbridge Housing Market Area Housing Market Settlement/Parish Area Woodbridge Alderton, Bawdsey, Blaxhall, Boulge, Boyton, Bredfield, Bromeswell, Burgh, Butley, Campsea Ashe, Capel St Andrew, Charsfield, Chillesford, Clopton, Cretingham, Dallinghoo, Debach, Eyke, Gedgrave, Great Bealings, Hacheston, Hasketon, Hollesley, Hoo, Iken, Letheringham, Melton, Melton Park, Monewden, Orford, Otley, Pettistree, Ramsholt, Rendlesham, Shottisham, Sudbourne, Sutton, Sutton Heath, Tunstall, Ufford, Wantisden, Wickham Market, Woodbridge Settlements & Parishes with no maps Settlement/Parish No change in settlement due to: Boulge Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Bromeswell No Physical Limits, no defined Area to be Protected from Development (AP28) Burgh Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Capel St Andrew Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Clopton No Physical Limits, no defined Area to be Protected from Development (AP28) Dallinghoo Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Debach Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Gedgrave Settlement in Countryside (as defined in Policy SP19 Settlement Hierarchy) Great Bealings Currently working on a Neighbourhood -

In England, Scotland, and Wales: Texts, Purpose, Context, 1138-1530

Victoria Shirley The Galfridian Tradition(s) in England, Scotland, and Wales: Texts, Purpose, Context, 1138-1530 A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Literature Cardiff University 2017 i Abstract This thesis examines the responses to and rewritings of the Historia regum Britanniae in England, Scotland, and Wales between 1138 and 1530, and argues that the continued production of the text was directly related to the erasure of its author, Geoffrey of Monmouth. In contrast to earlier studies, which focus on single national or linguistic traditions, this thesis analyses different translations and adaptations of the Historia in a comparative methodology that demonstrates the connections, contrasts and continuities between the various national traditions. Chapter One assesses Geoffrey’s reputation and the critical reception of the Historia between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries, arguing that the text came to be regarded as an authoritative account of British history at the same time as its author’s credibility was challenged. Chapter Two analyses how Geoffrey’s genealogical model of British history came to be rewritten as it was resituated within different narratives of English, Scottish, and Welsh history. Chapter Three demonstrates how the Historia’s description of the island Britain was adapted by later writers to construct geographical landscapes that emphasised the disunity of the island and subverted Geoffrey’s vision of insular unity. Chapter Four identifies how the letters between Britain and Rome in the Historia use argumentative rhetoric, myths of descent, and the discourse of freedom to establish the importance of political, national, or geographical independence. Chapter Five analyses how the relationships between the Arthur and his immediate kin group were used to challenge Geoffrey’s narrative of British history and emphasise problems of legitimacy, inheritance, and succession.