Making Work Play at the New American School by Christopher Otter Sims a Dissertation Submitted in Parti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nov 2014 Dummy.Indd

NOVEMBERJULY 20102014 •• TAXITAXI INSIDERINSIDER •• PAGEPAGE 11 INSIDER VOL. 15, NO. 11 “The Voice of the NYC Transportation Industry.” NOVEMBER 2014 Letters Start on Page 3 EDITORIAL • By David Pollack Insider News Page 5 • Taxi Drivers and Ebola Updated Relief Stands Thankfully there is a radio show where you can Taxi Dave (that’s me!) not only had the Chairwoman get fi rst hand information needed to answer any of of the TLC, Meera Joshi discuss fears of the Ebola Page 6 your questions whether industry related or even virus, but I had Dr. Jay Varma, a spokesperson from • health related. the NYC Department of Health answering all ques- Taxi Attorney Before we get into Ebola, TLC Chair- tions that drivers brought to “Taxi Dave’s” By Michael Spevack woman Joshi stated that the TLC will attention. How does Ebola spread? What be sending out warning letters to drivers is the best means of prevention and pro- Page 7 instead of summonses for a red light tection? • camera offense. “Vision Zero is not Chairwoman Joshi stated, “Thank you How I Became A Star about penalties,” she stated. To hear this for reaching out to the Department of By Abe Mittleman and much more, listen to this link: http:// Health. The myth of how Ebola spreads is www.wor710.com/media/podcast-the- spreading incredibly faster than the actual Page 15 taxi-dave-show-TaxiInsider/the-taxi-dave- disease ever could. It is really important to • show-102614-25479519/ separate facts from fi ction and the Depart- Street Talk Folks, if you want fi rst hand infor- ment of Health has been doing an amazing By Erhan Tuncel mation, every Sunday evening at 8:00 job in getting that message out there and PM listen to WOR-710 radio to TAXI DAVE. -

Sky-High Landmark District

BROOKLYN’S REAL NEWSPAPERS Including The Brooklyn Heights Paper, Carroll Gardens-Cobble Hill Paper, DUMBO Paper, Fort Greene-Clinton Hill Paper and Downtown News Published every Saturday — online all the time — by Brooklyn Paper Publications Inc, 55 Washington St, Suite 624, Brooklyn NY 11201. Phone 718-834-9350 • www.BrooklynPapers.com • © 2005 Brooklyn Paper Publications • 16 pages •Vol.28, No. 10 BWN • Saturday, March 5, 2005 • FREE SKY-HIGH BKLYN STATE SENATOR TO CITY: LANDMARK DISTRICT Heights civics seek to protect buildings near Borough Hall By Jess Wisloski buildings or larger complexes The Brooklyn Papers under the Downtown Brooklyn Rezoning Plan approved last With the help of a preserva- summer. tion group, the Brooklyn “These are very distin- Heights Association is pro- guished commercial buildings moting a plan to preserve sev- built by the best architects of eral high-rise office buildings the day,” said Herrera, technical just outside the Brooklyn services director of the Land- Heights Historic District. marks Conservancy. Herrera Calling it the “Borough Hall said the movement came about Skyscraper Historic District,” after St. Francis College began BHA President Nancy Bowe demolition of the McGarry Li- touted the proposal at her brary last year at 180 Remsen group’s annual meeting last St. month. “Some of them have been The compact district would abused and knocked around, “butt up against” the Brooklyn but they could be restored and Heights Historic District, ac- really bought back to their cording to the proposal’s coor- best,” he said, and called the dinator, BHA governor Alex proposed district a “real history Showtime Herrera, who also works for the lesson” on the days when “the New York Landmarks Conser- best architects in New York vancy. -

He Dreams of Giants

From the makers of Lost In La Mancha comes A Tale of Obsession… He Dreams of Giants A film by Keith Fulton and Lou Pepe RUNNING TIME: 84 minutes United Kingdom, 2019, DCP, 5.1 Dolby Digital Surround, Aspect Ratio16:9 PRESS CONTACT: Cinetic Media Ryan Werner and Charlie Olsky 1 SYNOPSIS “Why does anyone create? It’s hard. Life is hard. Art is hard. Doing anything worthwhile is hard.” – Terry Gilliam From the team behind Lost in La Mancha and The Hamster Factor, HE DREAMS OF GIANTS is the culmination of a trilogy of documentaries that have followed film director Terry Gilliam over a twenty-five-year period. Charting Gilliam’s final, beleaguered quest to adapt Don Quixote, this documentary is a potent study of creative obsession. For over thirty years, Terry Gilliam has dreamed of creating a screen adaptation of Cervantes’ masterpiece. When he first attempted the production in 2000, Gilliam already had the reputation of being a bit of a Quixote himself: a filmmaker whose stories of visionary dreamers raging against gigantic forces mirrored his own artistic battles with the Hollywood machine. The collapse of that infamous and ill-fated production – as documented in Lost in La Mancha – only further cemented Gilliam’s reputation as an idealist chasing an impossible dream. HE DREAMS OF GIANTS picks up Gilliam’s story seventeen years later as he finally mounts the production once again and struggles to finish it. Facing him are a host of new obstacles: budget constraints, a history of compromise and heightened expectations, all compounded by self-doubt, the toll of aging, and the nagging existential question: What is left for an artist when he completes the quest that has defined a large part of his career? 2 Combining immersive verité footage of Gilliam’s production with intimate interviews and archival footage from the director’s entire career, HE DREAMS OF GIANTS is a revealing character study of a late-career artist, and a meditation on the value of creativity in the face of mortality. -

Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society

Capri Community Film Society Papers Guide to the Papers of the Capri Community Film Society Auburn University at Montgomery Archives and Special Collections © AUM Library Written By: Rickey Best & Jason Kneip Last Updated: 2/19/2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Content Page # Collection Summary 2 Administrative Information 2 Restrictions 2-3 Index Terms 3 Agency History 3-4 1 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Scope and Content 5 Arrangement 5-10 Inventory 10- Collection Summary Creator: Capri Community Film Society Title: Capri Community Film Society Papers Dates: 1983-present Quantity: 6 boxes; 6.0 cu. Ft. Identification: 92/2 Contact Information: AUM Library Archives & Special Collections P.O. Box 244023 Montgomery, AL 36124-4023 Ph: (334) 244-3213 Email: [email protected] Administrative Information Preferred Citation: Capri Community Film Society Papers, Auburn University Montgomery Library, Archives & Special Collections. Acquisition Information: The collection began with an initial transfer on September 19, 1991. A second donation occurred in February, 1995. Since then, regular donations of papers occur on a yearly basis. Processed By: Jermaine Carstarphen, Student Assistant & Rickey Best, Archivist/Special Collections Librarian (1993); Jason Kneip, Archives/Special Collections Librarian. Samantha McNeilly, Archives/Special Collections Assistant. 2 of 64 Capri Community Film Society Papers Restrictions Restrictions on access: Access to membership files is closed for 25 years from date of donation. Restrictions on usage: Researchers are responsible for addressing copyright issues on materials not in the public domain. Index Terms The material is indexed under the following headings in the Auburn University at Montgomery’s Library catalogs – online and offline. -

Exploring Films About Ethical Leadership: Can Lessons Be Learned?

EXPLORING FILMS ABOUT ETHICAL LEADERSHIP: CAN LESSONS BE LEARNED? By Richard J. Stillman II University of Colorado at Denver and Health Sciences Center Public Administration and Management Volume Eleven, Number 3, pp. 103-305 2006 104 DEDICATED TO THOSE ETHICAL LEADERS WHO LOST THEIR LIVES IN THE 9/11 TERROIST ATTACKS — MAY THEIR HEORISM BE REMEMBERED 105 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 106 Advancing Our Understanding of Ethical Leadership through Films 108 Notes on Selecting Films about Ethical Leadership 142 Index by Subject 301 106 PREFACE In his preface to James M cG regor B urns‘ Pulitzer–prizewinning book, Leadership (1978), the author w rote that ―… an im m ense reservoir of data and analysis and theories have developed,‖ but ―w e have no school of leadership.‖ R ather, ―… scholars have worked in separate disciplines and sub-disciplines in pursuit of different and often related questions and problem s.‖ (p.3) B urns argued that the tim e w as ripe to draw together this vast accumulation of research and analysis from humanities and social sciences in order to arrive at a conceptual synthesis, even an intellectual breakthrough for understanding of this critically important subject. Of course, that was the aim of his magisterial scholarly work, and while unquestionably impressive, his tome turned out to be by no means the last word on the topic. Indeed over the intervening quarter century, quite to the contrary, we witnessed a continuously increasing outpouring of specialized political science, historical, philosophical, psychological, and other disciplinary studies with clearly ―no school of leadership‖with a single unifying theory emerging. -

Quentin Couldn't

The Arts and Entertainment Supplement to the Daily Nexus, for April 13th through April 19th. 1995 Quentin couldn't: make it, but we got the inside scoop» on Destiny- Turns on tJie Ftedio from his co-stars Dylan McDermott and Nancy Travis, along with director Jack Bar an. See pages 4A-5A. 2A Thursday, April 13,1993 Daily Nexus bars of cage / you see scars, much ease — thus “Strug results of my rage.” That’s glin’,” tire soul food, hip- another thing about this hop blues, demi-epic of debut album. In Tricky’s the album. (The “epic” Massive and Unparalleled world, everything is a cage, track would probably be without any hope of re the seven-minute exten prieve. Even love is a sti sion of their first single, T ricky posedly one of 'fricky’s landic woman named any of them out from the fling, repressive activity “Aftermath.”) Amid creak M axinquaye nonsense words, sort of Ragga (again, no last scrapyard beats, hip-hop and sex is the violent ing doors, screeching 4th S t Broadway/I gland based around the name of name) and Alison Gold- breaks, soul slides and means of expressing one’s saxes, cocking rifles and his mother. frapp, who was most re thick, dark atm osphere anger. ambulance wails, Tricky This is almost too dense While we’re on names, cently heard on Orbital’s that just oozes out all over Witness “Abbaon Fat mutters like a junkie com a record for one head to Tricky’s real one is Adrian last album. -

PELLE the CONQUEROR (Pelle Erobreren) Directed by Bille August

presents A 30th Anniversary Restoration PELLE THE CONQUEROR (Pelle erobreren) Directed by Bille August “[T]he film is a towering achievement…an exhilarating experience unlikely to be forgotten.” – Kevin Thomas, Los Angeles Times Denmark, Sweden / 1987 / Drama / Danish and Swedish with English subtitles 157 min / 1.66: 1 / 2K scan from original 35mm negative Film Movement Contacts: Genevieve Villaflor | Press | (212) 941-7744 x215 | [email protected] Clemence Taillandier |Theatrical Booking | (212) 941-7744 x301 | [email protected] Assets: Official Trailer: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wIoZ5OYc9RE Downloadable hi-res images: http://www.filmmovement.com/filmcatalog/index.asp?MerchandiseID=537 SELECT PRESS "The von Sydow performance is in a category by itself. It is another highlight in an already extraordinary career, and quite unlike anything that American audiences have seen him do to date." – Vincent Canby, New York Times “Visually speaking, the film is handsome….Then again, perhaps the real secret to PELLE’s demographic-crossing appeal is the presence of the great von Sydow…” – A.A. Dowd, AV Club “In Bille August's PELLE THE CONQUEROR, Max von Sydow is so astoundingly evocative that he makes your bones ache.” – Hal Hinson, The Washington Post “The film is a richness of events….there is not a bad performance in the movie, and the newcomer, Pelle Hvenegaard, never steps wrong in the title role....It is Pelle, not Lasse, who is really at the center of the movie, which begins when he follows his father’s dream, and ends as he realizes he must follow his own.” – Roger Ebert, RogerEbert.com SYNOPSIS Lasse (Max von Sydow), an elderly and widowed farmer, and his young son Pelle join a boat-load of immigrants to escape from impoverished rural Sweden to Denmark's Baltic island of Bornholm. -

Timeline of Selected Bergman 100 Events

London, 18.09.17 Timeline of selected Bergman 100 events This timeline includes major activities before and during the Bergman year. Please note that there are many more events to be announced both within this timeframe and beyond. A full, regularly updated calendar of performances, retrospectives, exhibitions and other events is available at www.ingmarbergman.se September 2017 • Misc.: Launch of Bergman 100, 18 Sep, London, UK. • On stage: Scenes from a marriage, opening 31 Aug, Det Kgl Teater (The Royal Playhouse), Copenhagen, Denmark. • On stage: Autumn Sonata (opera), opening 8 Sep, Finnish National Opera, Helsinki, Finland. • Book release: Ingmar Bergman A–Ö (in English), Ingmar Bergman Foundation/Norstedts publishing, Sweden. • On stage: The Best Intentions, opening 16 Sep, Aarhus theatre, Aarhus, Denmark. • On stage: After the Rehearsal/Persona, The Barbican, London, UK. • On stage: Scenes From a Marriage, opening 20 Sep, Teatros del Canal, Madrid, Spain. • On stage: Breathe, Bergman-inspired dance performance, opening 28 Sep, Inkonst, Malmö, Sweden. • On stage: The Serpent’s Egg, opening 30 Sep, Cuvilliés-Theater, Munich, Germany. • On stage: Scenes From a Marriage, world tour Sep–Dec, Asia, Europe, South America. October 2017 • On stage: Scenes from a marriage, opening 5 Oct, Ernst-Deutsch-Theater, Hamburg, Germany. • On stage: After the rehearsal, opening 20 Oct, Düsseldorfer Schauspielhaus, Düsseldorf, Germany. • Misc.: The European Film Academy awards Hovs Hallar the title ‘Treasure of European Film Culture’. (A nature reserve in the county of Skåne, Sweden, Hovs Hallar is the location of the chess scene in The Seventh Seal.) • On stage: Scenes From a Marriage, opening 25 Oct, Teatro Tivoli, Barcelona, Spain. -

For Ingmar Bergman, Uppsala Was the Place of Childhood Uppsala Ist Für Ingmar Bergman Ein Ort Der Kindheitserinnerungen

For Ingmar Bergman, Uppsala was the place of childhood Uppsala ist für Ingmar Bergman ein Ort der Kindheitserinnerungen. Akademikvarnen [ 3 ] an dem Flüsschen Fyrisån als Bischofshaus, Steinwurf von der Domkyrkan [ 2 ], dem Schloß [ 6 ] und nicht zuletzt als auch die Wirklichkeit abgewandelt.) Das Uppsala stadshotell lag Bergmans Uppsala ist weniger ein geographischer Ort, sondern Der Epilog des Buches ist eigentlich ein Prolog, da sich das Gespräch, UPPSALA memories. This is where he was born, and although his In Uppsala ist er zur Welt gekommen, und auch als die Familie deren Räumlichkeiten heute vom Museum Upplandsmuseet genutzt dem Kino Slottsbiografen [ 7 ] entfernt. wirklich dort, ist aber inzwischen geschlossen. vielmehr eine Welt aus Kindertagen, die zum Mythos erhoben wird. welches dort stattfindet, bereits vor dem Rest der Handlung zugetragen family moved to Stockholm not long after his birth, he kurz darauf nach Stockholm zog, verbrachte er viel Zeit bei seiner werden. Das rauschende Wasser des Flusses ist ein Leitmotiv, das hat. Anna und ihr Konfirmationspastor Jacob führen dieses Gespräch; Zeit, die verstreicht, Glocken, die schlagen und Uhren, die ticken, Ebenso wenig wie es jemals Märtas Matsalar gegeben hat, ist auch der spent a great deal of time at his maternal grandmother’s in Großmutter in Uppsala. Die Stadt nimmt in Ingmar Bergmans Werk den gesamten Film durchzieht. sie setzen sich auf eine Bank vor der Kirche, über die Jacob folgendes Uppsala är för Ingmar Bergman barndomens och minnenas Uppsala. Appearing in his work as of a sort of Arcadia, a die Bedeutung eines Arkadien, einer verlorenen Welt ein und spielt Die besten Absichten gehören in Bergmans Filmen und Büchern zum Inventar: „Die Kastanien Ort, an dem die Auseinandersetzung zwischen den Rivalinnen Anna zu berichten weiß: „Weißt du, daß die Trefaldighet-Kirche ursrprünglich ort. -

Columbia University Spring 2004 Tentative Syllabus Swedish-Comp

Columbia University Spring 2004 Tentative Syllabus Swedish-Comp. Lit. W3270 Ingmar Bergman and the Development of Scandinavian Film Instructor: Verne Moberg Phone: 212/854-4015 (office) Time: 11:00-3:00 P.M., Fridays Office: 415 Hamilton Hall E-mail: [email protected] Place: 717 Hamilton Hall Office Hours: by appointment Purpose: To explore the growth of the various film traditions in Scandinavia, ranging from the introduction of silent film through the landmark contributions of Ingmar Bergman in Sweden over many decades, with Carl Dreyer and more recent directors in Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. Course Literature Print Texts: Handouts will be available on silent films, the films of Carl Dreyer, and basics about Ingmar Bergman. All students are required to read and study at least one of the following works by Bergman: Images: My Life in Film ( Arcade, NY, 1990); The Magic Lantern, his autobiography (Penguin, NY, 1987); or Sunday’s Children (1993). Also required reading are two of the following works about Bergman: Ingmar Bergman: An Artist’s Journey--on Stage, on Screen, in Print, edited by Roger W. Oliver (Arcade, NY, 1995); Gender and Representation in the Films of Ingmar Bergman by Marilyn Blackwell (Camden House, Columbia, S.C., 1997); Ingmar Bergman: The Art of Confession, by Hubert I. Cohen (Twayne Publishers, NY, 1993); and Between Stage and Screen: Ingmar Bergman Directs by Egil Törnquist (Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 1995). More information about Bergman can be found on the Internet in English and Swedish at <http://www.hem.passagen.se/vogler>. Other required reading includes handouts on later directors and Film in Sweden edited by Francesco Bono and Maaret Koskinen (Swedish Institute, Stockholm, 1997). -

Talks with Gromyko) at the Gerald R

Scanned from the Kissinger Reports on USSR, China, and Middle East Discussions (Box 1 - September 18-21, 1975 - Talks with Gromyko) at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library ~/NODIS/XGDS TALKS WITH GROMYKO September 18-21, 1975 ~/NODIS/XGDS • ! ~/NODIS/XGDS . TALKS WITH FOREIGN MINISTER GROMYKO September 18-21, 1975 DATE, TIME, & PLACE SUBJECTS Tab A G r omyko/President/HAK Tour d' horizon Thursday, Sept. 18, 1975 4: 30 p. m. Oval Office " Tab B. Gromyko/HAK SALT Friday, Sept. 19, 1975 4:00-6:04 p. m. Sta.te Dept., Conference Room Tab C Grotnyko/HAK Cyprus; CT B & Ban Friday, Sept... 19, 19t:5 on New Systems; Korea; 8:15-10:40 p. m. (dinner) MBFR; Middle East State Dept., Monroe-Madison Room Tab D Gromyko/HAK SALT Sunday, Sept•. 21, 1975 9: 30-11: 30 p. m. (dinner) Soviet Mission to UN, New York DEClM8IFH!O E.O. 12&68. SEC. 1.1 NSC MEMO. 11124t98, ITATE ~. OUtDEl~eS BY 1./0 ,HARA, DATE ./.!Jf24g.'j ~INODIS/XGDS SEC RET - XGDS (3) CLASSIFIED BY: HENRY A. KISSINGER ~SENSITIVE MEMORANDUM OF CONVERSATION PARTICIPANTS: USSR: Andrey A~ Gromyko, Minister of Foreign Affairs Mr. Kornienko, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Mr. Sukhodrev US: The President . Henry A. Kissinger, Secretary of State Helmut Sonnenfeldt, Counsellor, State Dept. Walter Stoessel, U.S. Ambassador to the USSR DATE & T~ME: September 18, 1975 - 4:30 p.m. PLACE: Oval Office, White House SUlBJECT:. Foreign Minister Gromyko' s CalIon The President The l're'sident: How is thE' General Secretary? ~ G.n~rnyko:. He is in good he<alth and he had a good vacation. -

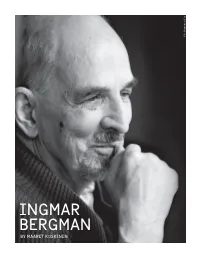

Ingmar Bergman by Maaret-Koskinen English.Pdf

Foto: Bengt Wanselius Foto: INGMAR BERGMAN BY MAARET KOSKINEN Ingmar Bergman by Maaret Koskinen It is now, in the year of 2018, almost twenty years ago that Ingmar Bergman asked me to “take a look at his hellofamess” in his private library at his residence on Fårö, the small island in the Baltic Sea where he shot many of his films from the 1960s on, and where he lived until his death in 2007, at the age of 89. S IT turned out, this question, thrown foremost filmmaker of all time, but is generally re Aout seemingly spontaneously, was highly garded as one of the foremost figures in the entire premeditated on Bergman’s part. I soon came to history of the cinematic arts. In fact, Bergman is understand that his aim was to secure his legacy for among a relatively small, exclusive group of film the future, saving it from being sold off to the highest makers – a Fellini, an Antonioni, a Tarkovsky – whose paying individual or institution abroad. Thankfully, family names rarely need to be accompanied by a Bergman’s question eventually resulted in Bergman given name: “Bergman” is a concept, a kind of “brand donating his archive in its entirety, which in 2007 name” in itself. was added to the UNESCO World Heritage List, and the subsequent formation of the Ingmar Bergman Bergman’s career as a cinematic artist is unique in Foundation (www.ingmarbergman.se). its sheer volume. From his directing debut in Crisis (1946) to Fanny and Alexander (1982), he found time The year of 2018 is also the commemoration of to direct more than 40 films, including some – for Bergman’s birth year of 1918.