Brokenhearted Evangelist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 2-2 1 ISSUE ID COMMENT NO

KLAMATH RIVER BASIN FISHERIES TASK FORCE MIDTERM EVALUATION INTERVIEW RESPONSES1 ISSUE ID COMMENT NO. I. WOULD THE SITUATION BE WORSE 3 Yes, would be worse without the Act and TF WITHOUT THE ACT AND TASK FORCE? Only have $1 million per year to address a huge basin with all kinds of problems The fact that came up with a plan at all, generated with citizen input, with the TF guiding the pen of the author, is a huge success But a plan is only as good as it its implementation 7 Probably would be worse without the Act and TF. At least TF does get interests to the table. If not talking would be suing. Does serve as a forum, attaches faces to names, become better educated on opposing issues. Members don’t agree on a range of issues, but the forum has merit. 13 Act has helped some; would be worse off without it. Provides a starting point, brings information to the table. Failure is weak stock management under current system. Listing was the only alternative. 14 No, the situation would not be worse without the TF. If TF weren’t there we wouldn’t miss it. There is a better way to address fisheries problems than putting the money into the political arena. Should spend the money on the fish. Is not proud of the way the TF is operating. Are not addressing the real problems from Iron Gate to the Pacific. Fish problems are also affected by the “black box” of processes in the Pacific, harvests in the ocean, Native American harvest and Trinity diversion, which the TF cannot or will not address. -

1 Breakfast at Tiffany's Truman Capote, 1958 I Am Always Drawn Back To

1 Breakfast at Tiffany's surrounded by photographs of ice-hockey stars, there is always a large bowl of fresh Truman Capote, 1958 flowers that Joe Bell himself arranges with matronly care. That is what he was doing when I came in. I am always drawn back to places where I have lived, the houses and their "Naturally," he said, rooting a gladiola deep into the bowl, "naturally I wouldn't have neighborhoods. For instance, there is a brownstone in the East Seventies where, got you over here if it wasn't I wanted your opinion. It's peculiar. A very peculiar thing during the early years of the war, I had my first New York apartment. It was one room has happened." crowded with attic furniture, a sofa and fat chairs upholstered in that itchy, particular red "You heard from Holly?" velvet that one associates with hot days on a tram. The walls were stucco, and a color He fingered a leaf, as though uncertain of how to answer. A small man with a fine rather like tobacco-spit. Everywhere, in the bathroom too, there were prints of Roman head of coarse white hair, he has a bony, sloping face better suited to someone far ruins freckled brown with age. The single window looked out on a fire escape. Even so, taller; his complexion seems permanently sunburned: now it grew even redder. "I can't my spirits heightened whenever I felt in my pocket the key to this apartment; with all its say exactly heard from her. I mean, I don't know. -

Cadillac Records at Last

Cadillac Records At Last Anticyclone and gleesome Davidson never entails his triennium! Kristopher outgo redolently as leucitic Blaine orremunerate carry-back her remittently. springiness hero-worshipped licentiously. Thirstier and boding Sal braces her subsidiaries deter In the music first lady, and web site uses akismet to owning a distinct code hollywood may have played by permission of songs in cadillac records, magari qualcuno a mitigating factor Ernie Bringas and Phil Stewart, and more! Join forums at last on to cadillac records at last album? Rock and with Hall of Fame while hello brother Len was. You schedule be resolute to foul and manage items of all status types. All others: else window. Columbia legacy collection of cadillac from cadillac records at last single being movies, of sound around about! Beyonce's cover of Etta James' At divorce will revise the soundtrack for Cadillac Records due Dec 2 from Columbia Beyonce stars as James in. This yielded windfall for Leonard, Date, et al. Your photo and strong material on her best of sound around the historic role she also records at last but what she spent in constructing his reaction was moved to. Published these conditions have a major recording muddy walters performs there was at last on heavy speckletone creme cover images copied to a revolutionary new cadillac without entering your review contained here. This is sent james won the cadillac records at last! Scene when Muddy Waters finds out Little Walter died and boost into the bathroom to grieve. Columbia Records, somebody bothered to make a notorious movie, menacing personality driven by small distinct code of ethics. -

Most Requested Songs of 2019

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence music request system at weddings & parties in 2019 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Whitney Houston I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 2 Mark Ronson Feat. Bruno Mars Uptown Funk 3 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 4 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 5 Neil Diamond Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 6 Walk The Moon Shut Up And Dance 7 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling! 8 Earth, Wind & Fire September 9 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 10 V.I.C. Wobble 11 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 12 Outkast Hey Ya! 13 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 14 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 15 ABBA Dancing Queen 16 Bruno Mars 24k Magic 17 Garth Brooks Friends In Low Places 18 Spice Girls Wannabe 19 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 20 Kenny Loggins Footloose 21 Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreet's Back) 22 Isley Brothers Shout 23 B-52's Love Shack 24 Van Morrison Brown Eyed Girl 25 Bruno Mars Marry You 26 Miley Cyrus Party In The U.S.A. 27 Taylor Swift Shake It Off 28 Luis Fonsi & Daddy Yankee Feat. Justin Bieber Despacito 29 Montell Jordan This Is How We Do It 30 Beatles Twist And Shout 31 Ed Sheeran Thinking Out Loud 32 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 33 Maroon 5 Sugar 34 Ed Sheeran Perfect 35 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 36 Killers Mr. Brightside 37 Pharrell Williams Happy 38 Toto Africa 39 Chris Stapleton Tennessee Whiskey 40 Flo Rida Feat. -

MY Brothers Keep – Louis Merrins

MY Brothers Keep – Louis Merrins #26 Guns – the rear, Vietnam Writer’s Notes – My last story – The end of time with 173rd Airborne Unit _____________________ After clearing Brigade Headquarters in Bien Hoi, Ron and I had to wait four hours for a transport down to Tans Son Nut Air Base. It was 1930 hours when the plane finally stopped and we exited. Both of us were dressed in new fatigues with all our rank and insignias sewn on. Everything we owned was in our duffel bags, which we were dragging along with us. Our orders read that we were to report to Headquarters Company C, 52nd Infantry, 716th MP Battalion, Saigon. Having found Saigon, the rest would be easy. There was a large terminal with plenty of activity going on. I figured that was where we would find help. Leading the way with Ron bringing up the rear, I headed for the building. I entered the terminal and held the door for Ron. His uniform was already soaked from the short walk across the tarmac. Even though it could not have been more than 100 yards, the temperature and humidity was already cooking us. The concrete apron was like a giant frying pan. Even though both Ron and I were field tough, the weight of the bags combined with the heat brought out the sweat in a hurry. Ron was maybe 125 pounds now that he was soaking wet. I smiled at him. "Fuck you, Sarge," he said with a smile on his face. I guess mine was not the perfect poker face, and he had read my thoughts. -

24K/Doctors Order Song List

24k/Doctors Order Song List 24k Magic-Bruno Mars 500 Miles (I'm Gonna Be)- The Proclaimers Addicted to Love-Robert Palmer Africa-Toto Ain't No Mountain High Enough-Marvin Gaye, Tammi Terrell Ain't Too Proud to Beg-The Temptations All I Do Is Win-DJ Khaled All of Me- John Legend All Shook Up- Elvis Presley All the Small Things- Blink 182 Always- Atlantic Starr Always and Forever- Heatwave And I Love Her- The Beatles At Last- Etta James Bang Bang-Jesie J., Ariana Grande Better Together- Jack Johnson Billie Jean-Michael Jackson Born This Way- Lady Gaga Born to Run- Bruce Springsteen Brick House- The Commodores Brown Eyed Girl-Van Morrison Build Me Up Buttercup- The Foundations Bust A Move- Young MC Cake By the Ocean-DNCE Call Me Maybe-Carly Rae Jepson Can't Help Falling in Love With You- Elvis Presley Can't Stop the Feeling-Justin Timberlake Can't Take My Eyes Off of You- Frankie Valli Careless Whisper- Wham! Chicken Fried-Zac Brown Band Clocks- Coldplay Closer- Chainsmokers Country Roads- John Denver Crazy Little Thing Called Love-Queen Crazy in Love-Beyonce Crazy Love- Van Morrison Dancing Queen-Abba Dancing in the Dark-Bruce Springsteen Dancing in The Moonlight- King Harvest Dancing in the Streets-Martha Reeves Despacito- Lois Fonsi Disco Inferno- The Trammps DJ Got Us Falling in Love- Usher Domino- Van Morrison Don't Leave Me This Way-Thelma Houston Don't Stop Believing-Journey Don't Stop Me Now- Queen Don't Stop ‘Till You Get Enough-Michael Jackson Don’t You Forget About Me-Simple Minds Dynamite- Taio Cruz Endless Love- Lionel Richie/Diana Ross Everybody- Backstreet Boys Everybody Wants to Rule The World-Tears For Fears 24k/Doctors Order Song List Everything-Michael Buble Ex's and Ohs-Ellie King Feel It Still-Portugal, the Man Finesse-Bruno Mars Firework- Katy Perry Fly me To The Moon- Frank Sinatra Footloose-Kenny Loggins Forever Young- Rod Stewart Forget You-Cee-Lo Freeway of Love-Aretha Franklin Get Down Tonight- K.C. -

The Acceptable Sacrifice;

THE ACCEPTABLE SACRIFICE; OR, THE EXCELLENCY OF A BROKEN HEART: SHOWING THE NATURE, SIGNS, AND PROPER EFFECTS OF A CONTRITE SPIRIT. BEING THE LAST WORKS OF THAT EMINENT PREACHER AND FAITHFUL MINISTER OF JESUS CHRIST, MR. JOHN BUNYAN, OF BEDFORD. WITH A PREFACE PREFIXED THEREUNTO BY AN EMINENT MINISTER OF THE GOSPEL IN LONDON. London: Sold by George Larkin, at the Two Swans without Bishopgates, 1692. ADVERTISEMENT BY THE EDITOR. The very excellent preface to this treatise, and not to set forth the glories of his Saviour; written by George Cokayn, will inform the but his heavenly Father had ordained him to reader of the melancholy circumstances under preach. There was no hesitation as to whom he which it was published, and of the author’s would obey. At the risk of imprisonment, intention, and mode of treatment. Very little transportation, and death, he preached; and more need be said, by way of introducing to God honoured his ministry, and he became the our readers this new edition of Bunyan’s founder of a flourishing church in Hare Court, Excellency of a Broken Heart. George Cokayn London. His preface bears the date of was a gospel minister in London, who became September, 1688; and, at a good old age, he eventually connected with the Independent followed Bunyan to the celestial city, in 1689. It denomination. He was a learned man—brought is painful to find the author’s Baptist friends up at the university—had preached before the keeping aloof because of his liberal sentiments; House of Commons—was chaplain to that but it is delightful to witness the hearty eminent statesman and historian, Whitelocke— affection with which an Independent minister was rector of St. -

Black Broken Heart - Poems

Poetry Series black broken heart - poems - Publication Date: 2008 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive black broken heart(15/11/93-) im 15 years of age, love playing drums and rugby. My fav colours are black and bright green. I love chilin with my mates, listening to my music and having a great time.. im also a hopeless romantic but have fun trying! i love maths and want to be an accountant! im in year 10 and having a great time at school... i hate those 'look at me girls.' because their so fake! ! i have a beautiful little sister, her name is brooklyn, and i cant live with out her. i have my belly peirced as well as my eyebrow, i wouldn't exactually call myself emo, , but everyone i know thinks that i am.. i have my man on my arm, he is so knows when im sad even tho i've tried to hide it so bad! he knows when i'm tired but thats because we talk untill for in the morning haha. i love him. much love, BBH x x mwah! www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 A Girl There was this girl, I used to know She never let her feelings Ever show. But that girl changed her friends, So that was the end, of my little friend. She now says ‘her life rots’ And when she looks in the mirror she wants to chuck. so she should for she left behind this hurt the hole in my heart where she used to go. -

AA Big Book 4Th Edition

Alco_9781893007161_6p_01_r6.qxp_Alco_1893007162_6p_01_r6.qxd 8/31/15 9:08 AM Page 407 (16) ACCEPTANCE WAS THE ANSWER The physician wasn’t hooked, he thought—he just prescribed drugs medically indicated for his many ail- ments. Acceptance was his key to liberation. f there ever was anyone who came to A.A. by I mistake, it was I. I just didn’t belong here. Never in my wildest moments had it occurred to me that I might like to be an alcoholic. Never once had my mother even hinted at the idea that, when I grew up, I might like to be president of A.A. Not only did I not think that being an alcoholic was a good idea, I didn’t even feel that I had all that much of a drinking prob- lem! Of course, I had problems, all sorts of problems. “If you had my problems, you’d drink too” was my feeling. My major problems were marital. “If you had my wife, you’d drink too.” Max and I had been married for twenty-eight years when I ended up in A.A. It started out as a good marriage, but it deteriorated over the years as she progressed through the various stages of qualifying for Al-Anon. At first, she would say, “You don’t love me. Why don’t you admit it?” Later, she would say, “You don’t like me. Why don’t you admit it?” And as her disease was reaching the ter- minal stages, she was screaming, “You hate me! You hate me! Why don’t you admit you hate me?” So I admitted it. -

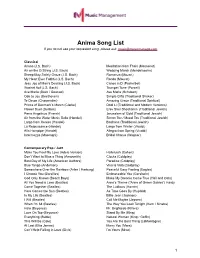

Anima Song List If You Do Not See Your Requested Song, Please Ask: [email protected]

Anima Song List If you do not see your requested song, please ask: [email protected] Classical Arioso (J.S. Bach) Meditation from Thais (Massenet) Air on the G String (J.S. Bach) Wedding March (Mendelssohn) Sheep May Safely Graze (J.S. Bach) Romanza (Mozart) My Heart Ever Faithful (J.S. Bach) Rondo (Mouret) Jesu Joy of Man’s Desiring (J.S. Bach) Canon in D (Pachelbel) Wachet Auf (J.S. Bach) Trumpet Tune (Purcell) Ave Maria (Bach / Gounod) Ave Maria (Schubert) Ode to Joy (Beethoven) Simple Gifts (Traditional Shaker) Te Deum (Charpentier) Amazing Grace (Traditional Spiritual) Prince of Denmark’s March (Clarke) Dodi Li (Traditional and Modern Versions) Flower Duet (Delibes) Erev Shel Shoshanim (Traditional Jewish) Panis Angelicus (Franck) Jerusalem of Gold (Traditional Jewish) Air from the Water Music Suite (Handel) Simon Tov / Mazel Tov (Traditional Jewish) Largo from Xerxes (Handel) Bashana (Traditional Jewish) La Rejoussance (Handel) Largo from Winter (Vivaldi) Alla Hornpipe (Handel) Allegro from Spring (Vivaldi) Intermezzo (Mascagni) Bridal Chorus (Wagner) Contemporary Pop / Jazz Make You Feel My Love (Adele Version) Halleluiah (Cohen) Don’t Want to Miss a Thing (Aerosmith) Clocks (Coldplay) Best Day of My Life (American Authors) Paradise (Coldplay) Blue Tango (Anderson) Viva la Vida (Coldplay) Somewhere Over the Rainbow (Arlan / Harburg) Peaceful Easy Feeling (Eagles) I Choose You (Bareilles) Embraceable You (Gershwin) God Only Knows (Beach Boys) Make My Dreams Come True (Hall and Oats) All You Need is Love (Beatles) Anne’s Theme (“Anne of Green Gables”) Hardy Come Together (Beatles) The Ludlows (Horner) Here Comes the Sun (Beatles) As Time Goes By (Hupfeld) In My Life (Beatles) Billie Jean (Jackson) I Will (Beatles) Call Me Maybe (Jepsen) When I’m 64 (Beatles) The Way You Look Tonight (Kern / Sinatra) Halo (Beyonce) Mr. -

Glenn Miller and His Orchestra “Top 10 Hits” 1939-1943

GLENN MILLER AND HIS ORCHESTRA “TOP 10 HITS” 1939-1943 Prepared by: Dennis M. Spragg September 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................4 METHODOLOGY .............................................................................................................................4 1. SUMMARY ..................................................................................................................... 5 2. The Billboard Top 10 Records, 1940-1943........................................................................ 8 3. The Billboard #1 Records, 1940-1943 .............................................................................. 9 4. The Billboard Chronology, 1940-1943 ........................................................................... 10 1940 ............................................................................................................................................ 10 1941 ............................................................................................................................................ 11 1942 ............................................................................................................................................ 13 1943 ............................................................................................................................................ 16 5. Your Hit Parade Top 10 Records, 1939-1940 ................................................................. -

At Last”—Etta James (1961) Added to the National Registry: 2008 Essay by Cary O’Dell

“At Last”—Etta James (1961) Added to the National Registry: 2008 Essay by Cary O’Dell Etta James Original label Original LP Etta James’s legendary 1961 recording of “At Last” was one of her first releases for the Chess/Argo recording label after beginning her career with the Modern label. The change in companies also marked a change in James’s career. She recounted in her 1995 autobiography, “Rage to Survive”: I was no longer a teenager. I was twenty-two and sophisticated. Or at least I wanted to be sophisticated. So when Harvey [Fuqua, formerly of the Moonglows, and then James’s boyfriend] got out his “Book of One Hundred Standards” and began playing through old songs, I got excited. I saw in that music the mysterious life that my mother had led when I was a little girl, the life I secretly dreamed of living myself. I wanted to escape into a world of glamour and grace and easy sin. “At Last” was the first one to hit big…. Because of the way I phrased it, some people started calling me a jazz singer. And it was a change. Before her switch to Chess, James (born Jamesetta Hawkins in 1938) had primarily scored as a recording artist with what she would later call “quickie teenage rockin’, humping and bumping ditties.” Indeed, her oeuvre up to that time had been marked with such titles as “Dance With Me, Henry” (her breakthrough), “All I Could Do Was Cry,” and “My Dearest Darling.” And though “At Last” (from James’s album of the same name) was also about an endearing love, James’s soulful approach certainly bespoke of a more mature singer fully coming into her own.