Issue 8 Autumn 2008

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drinker Solihull

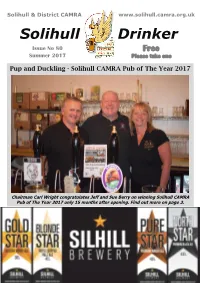

Solihull & District CAMRA www.solihull.camra.org.uk Solihull Drinker Issue No 80 Free Summer 2017 Please take one Pup and Duckling - Solihull CAMRA Pub of The Year 2017 Chairman Carl Wright congratulates Jeff and Sue Berry on winning Solihull CAMRA Pub of The Year 2017 only 15 months after opening. Find out more on page 3. Reserved for SILHILL Advert Page 1 Silhill Banner Advert .pdf THE NAGS HEAD Opening hours: 5 Real Ales at all times Monday—Thursday 12—11pm Friday—Sunday 12—Midnight Henley Music Festival Meals served Friday 25th - Monday 28th August Weekdays 12—3pm & 6pm —9pm Join us for Live Music and more! Saturday 12— 9pm Food available Sunday 12— 7pm Free Entry www.thenagsheadhenley.co.uk Book our beautiful garden for your private event. Wedding or Garden Party 161 High St, Henley-in-Arden The Nags Head B95 5BA Henley In Arden Tel : 01564 793120 2 Solihull CAMRA Pub of The Year Award 2017 On Friday 4th February 2016 at 5.00pm the Pup and Duckling, and wish it, and the first paying customers arrived at the Berry family, success for the rest of the Pup and Duckling, met by an ad- the year and the foreseeable future.” mittedly nervous Jeff Berry. Jeff thanked CAMRA for their support On Wednesday 17th May 2017, after since he opened, and spoke about how around 450 different beers had been things have moved on since that nerv- sold, Solihull CAMRA arrived to present ous opening. Jeff and his family with the 2017 Pub The first year has seen a continual in- of The Year award. -

Outstanding Actions

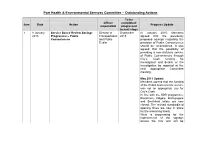

Port Health & Environmental Services Committee – Outstanding Actions To be Officer completed/ Item Date Action Progress Update responsible progressed to next stage 1. 8 January Service Based Review Savings Director of September In January 2015, Members 2013 Programme – Public Transportation 2015 agreed that the previously Conveniences and Public proposed savings regarding the Realm provision of Public Conveniences should be reconsidered. It was agreed that the possibility of providing a non-statutory service of Public Conveniences through City’s Cash funding be investigated and details of the investigation be reported at the next appropriate Committee meeting. May 2015 Update Members agreed that the funding of the Public Convenience service was not an appropriate use for City’s Cash. In line with the SBR programme, Blackfriars, Aldgate, Bishopsgate and Smithfield toilets are now closed. The revised standardised opening times are now in place for the remaining toilets. Work is progressing for the improvement of the signage across the City and will be To be Officer completed/ Item Date Action Progress Update responsible progressed to next stage installed over the next 3-6 months due to the bespoke design of way finders. Progress is being made on the re- location of the APC from Aldermanbury to Smithfield. 2. 20 January Prudent Passage, EC2 Assistant Ongoing Prudence passage is currently 2015 Cleansing swept once a day, it has cigarette Director bins fitted and signage in place, our Street Environment Officers (SEO) patrol the area regularly and speak to smokers to encourage responsible behaviour, SEO’s issue FPNs and request ad hoc sweeps from Amey when the passage is found to heavily soiled. -

The Golden Ratio for Social Marketing

30/ 60/ 10: The Golden Ratio for Social Marketing February 2014 www.rallyverse.com @rallyverse In planning your social media content marketing strategy, what’s the right mix of content? Road Runner Stoneyford Furniture Catsfield P. O & Stores Treanors Solicitors Masterplay Leisure B. G Plating Quality Support Complete Care Services CENTRAL SECURITY Balgay Fee d Blends Bruce G Carrie Bainbridge Methodist Church S L Decorators Gomers Hotel Sue Ellis A Castle Guest House Dales Fitness Centre St. Boniface R. C Primary School Luscious C hinese Take Away Eastern Aids Support Triangle Kristine Glass Kromberg & Schubert Le Club Tricolore A Plus International Express Parcels Miss Vanity Fair Rose Heyworth Club Po lkadotfrog NPA Advertising Cockburn High School The Mosaic Room Broomhill Friery Club Metropolitan Chislehurst Motor Mowers Askrigg V. C School D. C Hunt Engineers Rod Brown E ngineering Hazara Traders Excel Ginger Gardens The Little Oyster Cafe Radio Decoding Centre Conlon Painting & Decorating Connies Coffee Shop Planet Scuba Aps Exterior Cleaning Z Fish Interpretor Czech & Slovak System Minds Morgan & Harding Red Leaf Restaurant Newton & Harrop Build G & T Frozen Foods Council on Tribunals Million Dollar Design A & D Minicoaches M. B Security Alarms & Electrical Iben Fluid Engineering Polly Howell Banco Sabadell Aquarius Water Softeners East Coast Removals Rosica Colin S. G. D Engineering Services Brackley House Aubergine 262 St. Marys College Independent Day School Arrow Vending Services Natural World Products Michael Turner Electrical Himley Cricket Club Pizz a & Kebab Hut Thirsty Work Water Coolers Concord Electrical & Plumbing Drs Lafferty T G, MacPhee W & Mcalindan Erskine Roofing Rusch Manufacturing Highland & Borders Pet Suppl ies Kevin Richens Marlynn Construction High Definition Studio A. -

A Walk from Charing Cross to St Paul's

A walk from Charing Cross to St Paul’s Updated: 24 May 2020 Length: About 2½ miles Duration: Around 2½ hours “In the 1660s London dominated England’s political and economic life and, with a population of 450,000, was the fourth largest city in the world. Early Stuart London was made up of two districts – the City of London, a crowded square mile within the City walls, surrounded by fields and heathland, and to the west the village of Charing Cross and then Westminster.” GETTING HERE The walk can start at either Charing Cross station or Embankment station. If you are arriving by bus or on foot, then I suggest you head for Charing Cross station and turn down Villiers Street, which is on the left side of the station. If you are arriving at Charing Cross tube station, then follow the signs to Charing Cross National Rail station and then take Exit 2, marked Villiers Street and turn to the right down Villiers Street. 1 Walk down Villiers Street and when you reach the end of the row of shops and restaurants on the left-hand side, turn into the narrow gateway and walk down the flight of steps and along the terraced passageway known as Watergate Walk. If you’ve arrived at the Embankment station From Embankment Station leave via the left-hand exit (not the riverside) and walk up Villiers Street. Pass the two sets of gates that lead into the Victoria Gardens. When you reach the little stand-alone snacks and sweets shop turn right through the narrow gate and walk down the steps into Watergate Walk, passing Gordon’s Wine Bar on the left. -

Londra. Guida Visual

lOndra GuIda vIsuaL InfOrmazIOnI pratIChe lOndra GuIda vIsuaL InfOrmazIOnI pratIChe Touring Editore Direttore contenuti turistico-cartografici: Fiorenza Frigoni SOMMARIO Responsabile editoriale: Cristiana Baietta Realizzazione editoriale a cura della Banca Dati Turistica e del settore Cartografico di Touring Editore GUIDA ALLE INFORMAZIONI Hanno collaborato alla realizzazione del volume: PRATICHE pag. 4 Orietta Colombai, per il capitolo “In Viaggio” Alberto Santangelo, per il capitolo “Località” IN VIAGGIO pag. 6 NTL, per la traduzione di “Parole e frasi utili” > Informazioni utili APV Vaccani, per la redazione, l’impaginazione e la fotolito InfoCartoGrafica - Piacenza, per l’esecuzione cartografica > Trasporti > Salute e numeri di emergenza Pagliardini Associati, per il progetto grafico PAROLE E FRASI UTILI pag. 10 Grande cura e massima attenzione sono state poste, nel redigere questa guida, per garantire l’attendibilità e l’accuratezza delle informazioni. Non possiamo tuttavia assumerci GLOSSARIO GASTRONOMICO pag. 14 la responsabilità di cambiamenti d’orario, numeri telefonici, indirizzi, condizioni di accessibilità o altro sopraggiunti, né per danni o gli inconvenienti da chiunque subiti in conseguenza INDIRIZZI UTILI pag. 15 di informazioni contenute nella guida. ATLANTINO DELLA CITTÀ pag. 53 STAZIONI DELLE LINEE METROPOLITANE pag. 74 ©2012 Touring Editore Strada 1, Palazzo F9, 20090 Milanofiori-Assago (MI) www.touringclub.com Codice: H1619A EAN: 9788836562589 Allegato alla Guida Visual Londra Volume non in vendita Touring Club Italiano -

Pub Passport List

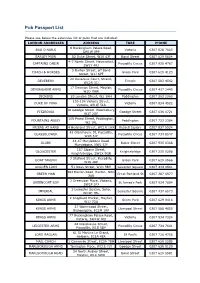

Pub Passport List Please see below the extensive list of pubs that are included: LONDON ADDRESSES ADDRESS TUBE PHONE 6 Buckingham Palace Road, BAG O NAILS Victoria 0207 828 7003 SW1W 0PP BARLEY MOW 82 Duke Street, W1K 6JF Bond Street 0207 629 5604 4-7 Norris Street, Haymarket, CAPTAINS CABIN Piccadilly Circus 0207 930 4767 SW1Y 4RJ 5 Burton Street, off Bond COACH & HORSES Green Park 0207 629 4123 Street, W1J 6PT 20 Devereux Court, Strand, DEVEREUX Temple 0207 583 4562 WC2R 3JJ 17 Denman Street, Mayfair, DEVONSHIRE ARMS Piccadilly Circus 0207 437 2445 W1D 7HW DICKENS 25 London Street, W2 1HH Paddington 0207 262 2365 130-134 Victoria Street, DUKE OF YORK Victoria 0207 834 4522 Victoria, SW1E 5LA 18 Goodge Street, Bloomsbury, FITZROVIA Goodge Street 0207 636 0721 W1T 2QF 109 Praed Street, Paddington, FOUNTAINS ABBEY Paddington 0207 723 2364 W2 1RL FRIEND AT HAND 4 Herbrand Street, WC1N 1HX Russell Square 0207 837 5524 42 Glasshouse St, Piccadilly, GLASSBLOWER Piccadilly Circus 0207 734 8547 W1B 5JY 43-47 Marylebone Road, GLOBE Baker Street 0207 935 6368 Marylebone, NW1 5JY 187 Sloane Street, GLOUCESTER Knightsbridge 0207 235 0298 Knightsbridge, SW1X 9QR 3 Stafford Street, Piccadilly, GOAT TAVERN Green Park 0207 629 0966 W1S 4RP GOLDEN LION 51 Dean Street, W1D 5BH Leicester Square 0207 434 0661 383 Euston Road, Euston, NW1 GREEN MAN Great Portland St 0207 387 6977 3AU 2 Greencoat Place, Victoria, GREENCOAT BOY St James’s Park 0207 834 7894 SW1P 1PJ 5 Leicester Square, Soho, IMPERIAL Leicester Square 0207 437 6573 WC2H 7BL 2 Shepherd Market, -

Woodies, New Malden (See Page 26) Tel: 020 7281 2786

D ON ON L Dec Vol 32 Jan No 6 2011 Woodies, New Malden (see page 26) Tel: 020 7281 2786 Steak & Ale House u We’re now taking bookings for all your Christmas parties and dinners. u Now serving festive ales! u 3 course Christmas meal for £21.00 u We’re open Christmas Day 12-4pm u Book your place at our popular free New Year’s Eve party Christmas ales, Christmas food ...Six Cask Marque and Christmas cheer! accredited real ales We hope to see you soon always on tap and You can follow us on Facebook for all events and updates and on 40+ malt and blended Twitter@north_nineteen whiskies also now on. Membership discounts on ale available, All proper, fresh pub sign up at www.northnineteen.co.uk food. In the main bar: Food is served: Tuesday - Live music and open mic 8pm start Wednesday - Poker Tournament 7.30pm start Tuesday-Friday 5-10pm Dart board and board games always available Saturday 12-10pm Prefer a quiet pint? Sunday 12-7pm Our Ale and Whisky Bar is open daily for food, drinks and conversation. We always have six well Cask Marque Please book your Sunday Roast kept real ales and 40+ top quality whiskies. accredited There are no strangers here, just friends you haven’t met yet Editorial London Drinker is published by Mike Hammersley on behalf of the London Branches of CAMRA, the Campaign for Real NDO Ale Limited, and edited by Geoff O N Strawbridge. L Material for publication should preferably be sent by e-mail to [email protected]. -

Sat. 7 July List of Pubs on Our Route, Either Historic, Famous, Or Just

CAMRA Richmond & Hounslow Branch Sat. 7 July List of pubs on our route, either historic, famous, or just interesting! Note timings given may not be adhered to as it depends what people prefer to do on the day – and then there is the possibility that England may have a World Cup match (if they beat Colombia on Tuesday) from 3.0 to 5.0pm which may interest some. It could be that the ‘West End’ part of the tour might be curtailed, e.g. omitting The Guinea. We’ll just have to see how it goes. Meet up: 12.0 The George 213 Strand WC2R 1AP Historic pub (1898); Greene King beers plus guests. www.whatpub.com/pubs/WLD/16277/george-london 12.30 Temple Brew House 46 Essex St. WC2R 3JF Not a historic pub, but as it’s a brewpub just round the corner from The George, it should be worth having a look and trying an Essex Street Brewery beer. Run by City Pub Co. – like the Rising Sun in (East) Twickenham. www.whatpub.com/pubs/WLD/16799/temple-brew-house-london 1.0 Old Bank of England 194 Fleet St. EC4A 2LT Not historically a pub, but a 1994 Fullers make-over of a famous old building. www.whatpub.com/pubs/ELC/14928/old-bank-of-england-london 1.30 Ye Olde Cock Tavern 22 Fleet St. EC4Y 1AA If you thought The George looked as if it is ‘squashed in’ by adjacent buidlings, you should see this one! Positively ‘squeezed’. A ‘Taylor Walker’ (now Greene King group) pub dating from 1887, although a fire in 1990 caused some restoration work to be done. -

P a Rt 6 P U B S & W in E B A

Nash’s Numbers Useful Information Document Part 6 PUBS & WINE BARS In alphabetical order. Only in the postcodes as follows IE1, E14, EC1, EC2, EC3, EC4, N1, NW1, SE1, SW1, SW3, SW5, SW6;SW7, SW10, W1, W2, W8, W11;WC1, WC2 PUBS & WINE BARS A PUBS & WINE BARS A 19:20,19,Great Sutton St,EC1 Allsop Arms,137,Gloucester Place,NW1 12 Bar Club,26,Denmark St,WC2 Alma,78,Chapel Market,N1 25 Canonbury Lane,25,Canonbury Lane,N1 Alma,59,Newington Green Rd,N1 8a,8a,Artillery Passage,E1 Alwyne Castle,,St.Pauls Rd,N1 A Monaghan,224,Camden High St,NW1 Ambarlounge,18,Kensington Church St,W8 Abbey Tavern,124,Kentish Town Rd,NW1 Anchor & Hope,36,Cut,SE1 Ad Lib,246,Fulham Rd,SW10 Anchor Tap,28,Horselydown Lane,SE1 Adam & Eve,81,Petty France,SW1 Anda Lucia,139,Whitfield St,W1 Ain'T Nothin But,20,Kingly St,W1 Angel,73,City Rd,EC1 Albert,11,Princess Rd,NW1 Angel,14,Crosswall,EC3 Albion,10,Thornhill Rd,N1 Angel,3,Islington High St,N1 Alibi,Hill House,Shoe Lane,EC4 Angel,61,St. Giles High St,WC2 All Bar One,18,Appold St,EC2 Angel & Crown,58,St. Martins Lane,WC2 PUBS & WINE PUBSWINE &BARS All Bar One,16,Byward St,EC3 Angel in the Fields,37,Thayer St,W1 All Bar One,84,Cambridge Circus,WC2 Angelic,57,Liverpool Rd,N1 All Bar One,103,Cannon St,EC4 Anglesea Arms,15,Sellwood Terrace,SW7 All Bar One,93a,Charterhouse St,EC1 Annabella Wine Bar,45,Clerkenwell Rd,EC1 All Bar One,36,Dean St,W1 Antelope Tavern,22,Eaton Terrace,SW1 Part 6 All Bar One,127,Finsbury Pavement,EC2 Apartment Bar,34,Threadneedle St,EC2 All Bar One,19,Henrietta St,WC2 Apollo,28,Paddington St,W1 All Bar -

London, City of Beer LESSER KNOWN BREWERIES! We Have More Than 50 Breweries in Greater London

F R E E Vol 36 Apr/May No 2 2014 The Year of the Horse comes to Battersea (photo Mike Flynn) – see page 22 Editorial London Drinker is published moving in the right direction at long last, on behalf of the perhaps because they have finally woken up London Branches of CAMRA, the to the fact that at present weekly closure Campaign for Real Ale Limited, rates of 28 pubs nationally and two in and edited by Tony Hedger. Greater London, the last pub in England Material for publication should preferably be will shut its doors in 2050. CAMRA sent by e-mail to [email protected]. PUBS AND THE GREATER LONDON continues to lobby national government to Correspondents unable to send letters to the close the planning loopholes and give our editors electronically may post them to ASSEMBLY’S LONDON PLAN Brian Sheridan at 4, Arundel House, Heathfield n early February, despite the hugely pubs sui generis planning use class. Whilst Road, Croydon CR0 1EZ. Isuccessful Battersea Beer Festival being in they claim to be listening, they are not Press releases should be sent by email to full swing and absorbing much of the senior acting. Local authority pub protection [email protected] hands in London Region, our vital policies are weak. In London we see far too Changes to pubs or beers should be reported to campaigning work on planning reform many examples of developers getting London Drinker, continued in earnest. James Watson from around them. Of course supermarkets and 9 Coppice Close, Raynes Park, London SW20 9AS East London & City Branch and Paul betting shops do not even need planning or by e-mail to [email protected]. -

The Dispensary, Aldgate (See Page 23) 1802-42 LD31-2:Layout 1 18/3/09 13:24 Page 2 1802-42 LD31-2:Layout 1 18/3/09 13:24 Page 3

1802-42 LD31-2:Layout 1 18/3/09 13:24 Page 1 D ON ON L April Vol 31 May No 2 2009 The Dispensary, Aldgate (see page 23) 1802-42 LD31-2:Layout 1 18/3/09 13:24 Page 2 1802-42 LD31-2:Layout 1 18/3/09 13:24 Page 3 Editorial London Drinker is published by Mike Hammersley on behalf of the London Branches of CAMRA, the NDON Campaign for Real Ale Limited, and O edited by Geoff Strawbridge. L Material for publication should preferably be sent by e-mail to [email protected]. Press releases should be sent by email to Tony Hedger, [email protected] Changes to pubs or beers should be reported to Capital Pubcheck, 2 Sandtoft Road, London SE7 7LR or by e-mail to [email protected]. For publication in April 2009, please send electronic documents to the Editor Let’s drink to our campaigning! no later than Tuesday 12th May. SUBSCRIPTIONS: £3.00 for mailing s we reach the end of the ahead of a formal launch in the of 6 editions or £6.00 for 12 should be ACAMRA year in London, and coming months ; many branches are sent to Stan Tompkins, 52 Rabbs Mill will be electing a new Regional already championing pubs that House, Chiltern View Road, Uxbridge, Director , it is an opportune time regularly sell cask ale brewed Middlesex, UB8 2PD (cheques payable to CAMRA London). for me to reflect on my time in that locally. ADVERTISING: Peter Tonge: position over the last five years or Our most tangible support for Tel: 020-8300 7693. -

Security Cover

Spirit Issuer plc (incorporated in England and Wales with limited liability under registered number 5266745) £150,000,000 Floating Rate Class A1 Secured Debenture Bonds due 2028 £200,000,000 Floating Rate Class A2 Secured Debenture Bonds due 2031 Issue Price: 100 per cent. Issue Price: 100 per cent. £250,000,000 Fixed/Floating Rate Class A3 Secured Debenture Bonds £350,000,000 Fixed/Floating Rate Class A4 Secured Debenture Bonds due 2021 due 2027 Issue Price: 105 per cent. Issue Price: 105 per cent. £300,000,000 Fixed/Floating Rate Class A5 Secured Debenture Bonds due 2034 Issue Price: 105 per cent. Unconditionally and irrevocably guaranteed in relation to Scheduled Interest and Ultimate Principal of the Class A1 Debenture Bonds, of the Class A3 Debenture Bonds and of the Class A5 Debenture Bonds by Ambac Assurance UK Limited It is expected that the £150,000,000 Floating Rate Class A1 Secured Debenture Bonds due 2028 (the Class A1 Debenture Bonds), the £200,000,000 Floating Rate Class A2 Secured Debenture Bonds due 2031 (the Class A2 Debenture Bonds), the £250,000,000 Fixed/Floating Rate Class A3 Secured Debenture Bonds due 2021 (the Class A3 Debenture Bonds), the £350,000,000 Fixed/Floating Rate Class A4 Secured Debenture Bonds due 2027 (the Class A4 Debenture Bonds) and the £300,000,000 Fixed/ Floating Rate Class A5 Debenture Bonds due 2034 (the Class A5 Debenture Bonds and, together with the Class A1 Debenture Bonds, the Class A2 Debenture Bonds, the Class A3 Debenture Bonds and the Class A4 Debenture Bonds, the Debenture Bonds) will be issued by Spirit Issuer plc (the Issuer) on 25 November, 2004 (the Closing Date).