Five Unpublished Coins of Alexander the Great and His Successors in the Rhodes University Collection1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lara O'sullivan, Fighting with the Gods

The Ancient History Bulletin VOLUME TWENTY-EIGHT: 2014 NUMBERS 3-4 Edited by: Edward Anson ò David Hollander ò Timothy Howe Joseph Roisman ò John Vanderspoel ò Pat Wheatley ò Sabine Müller ISSN 0835-3638 ANCIENT HISTORY BULLETIN Volume 28 (2014) Numbers 3-4 Edited by: Edward Anson, David Hollander, Sabine Müller, Joseph Roisman, John Vanderspoel, Pat Wheatley Senior Editor: Timothy Howe Editorial correspondents Elizabeth Baynham, Hugh Bowden, Franca Landucci Gattinoni, Alexander Meeus, Kurt Raaflaub, P.J. Rhodes, Robert Rollinger, Victor Alonso Troncoso Contents of volume twenty-eight Numbers 3-4 82 Lara O’Sullivan, Fighting with the Gods: Divine Narratives and the Siege of Rhodes 99 Michael Champion, The Siege of Rhodes and the Ethics of War 112 Alexander K. Nefedkin, Once More on the Origin of Scythed Chariot 119 David Lunt, The Thrill of Victory and the Avoidance of Defeat: Alexander as a Sponsor of Athletic Contests NOTES TO CONTRIBUTORS AND SUBSCRIBERS The Ancient History Bulletin was founded in 1987 by Waldemar Heckel, Brian Lavelle, and John Vanderspoel. The board of editorial correspondents consists of Elizabeth Baynham (University of Newcastle), Hugh Bowden (Kings College, London), Franca Landucci Gattinoni (Università Cattolica, Milan), Alexander Meeus (University of Leuven), Kurt Raaflaub (Brown University), P.J. Rhodes (Durham University), Robert Rollinger (Universität Innsbruck), Victor Alonso Troncoso (Universidade da Coruña) AHB is currently edited by: Timothy Howe (Senior Editor: [email protected]), Edward Anson, David Hollander, Sabine Müller, Joseph Roisman, John Vanderspoel and Pat Wheatley. AHB promotes scholarly discussion in Ancient History and ancillary fields (such as epigraphy, papyrology, and numismatics) by publishing articles and notes on any aspect of the ancient world from the Near East to Late Antiquity. -

Marina Gavryushkina UC Berkeley Art History 2013

UC Berkeley Berkeley Undergraduate Journal of Classics Title The Persian Alexander: The Numismatic Portraiture of the Pontic Dynasty Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7xh6g8nn Journal Berkeley Undergraduate Journal of Classics, 2(1) ISSN 2373-7115 Author Gavryushkina, Marina Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Undergraduate eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Gavryushkina 1 The Persian Alexander: The Numismatic Portraiture of the Pontic Dynasty Marina Gavryushkina UC Berkeley Art History 2013 Abstract: Hellenistic coinage is a popular topic in art historical research as it is an invaluable resource of information about the political relationship between Greek rulers and their subjects. However, most scholars have focused on the wealthier and more famous dynasties of the Ptolemies and the Seleucids. Thus, there have been considerably fewer studies done on the artistic styles of the coins of the smaller outlying Hellenistic kingdoms. This paper analyzes the numismatic portraiture of the kings of Pontus, a peripheral kingdom located in northern Anatolia along the shores of the Black Sea. In order to evaluate the degree of similarity or difference in the Pontic kings’ modes of representation in relation to the traditional royal Hellenistic style, their coinage is compared to the numismatic depictions of Alexander the Great of Macedon. A careful art historical analysis reveals that Pontic portrait styles correlate with the individual political motivations and historical circumstances of each king. Pontic rulers actively choose to diverge from or emulate the royal Hellenistic portrait style with the intention of either gaining support from their Anatolian and Persian subjects or being accepted as legitimate Greek sovereigns within the context of international politics. -

Seleucid Coinage and the Legend of the Horned Bucephalas

Seleucid coinage and the legend of the horned Bucephalas Autor(en): Miller, Richard P. / Walters, Kenneth R. Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Schweizerische numismatische Rundschau = Revue suisse de numismatique = Rivista svizzera di numismatica Band (Jahr): 83 (2004) PDF erstellt am: 04.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-175883 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch RICHARD P. MILLER AND KENNETH R.WALTERS SELEUCID COINAGE AND THE LEGEND OF THE HORNED BUCEPHALAS* Plate 8 [21] Balaxian est provincia quedam, gentes cuius Macometi legem observant et per se loquelam habent. Magnum quidem regnum est. Per successionem hereditariam regitur, quae progenies a rege Alexandra descendit et a filia regis Darii Magni Persarum... -

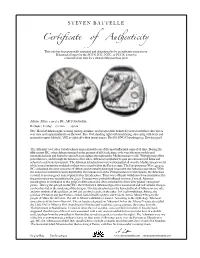

Ceificate of Auenticity

S T E V E N B A T T E L L E Ce!ificate of Au"enticity This coin has been personally inspected and determined to be an authentic ancient coin . If deemed a forgery by the ACCS, IGC, NGC, or PCGS, it may be returned at any time for a refund of the purchase price. Athens, Attica, 449-404 BC, AR Tetradrachm B076961 / U02697 17.1 Gm 25 mm Obv: Head of Athena right, wearing earring, necklace, and crested Attic helmet decorated with three olive leaves over visor and a spiral palmette on the bowl. Rev: Owl standing right with head facing, olive sprig with berry and crescent in upper left field, AOE to right; all within incuse square. Kroll 8; SNG Copenhagen 31; Dewing 1591-8 The Athenian “owl” silver tetradrachm is unquestionably one of the most influential coins of all time. During the fifth century BC, when Athens emerged as the greatest of all Greek cities, owls were the most widely used international coin and helped to spread Greek culture throughout the Mediterranean world. With the help of her powerful navy, and through the taxation of her allies, Athens accomplished to gain pre-eminance in Hellas and achieved a celebrated prosperity. The Athenian tetradrachms were well-accepted all over the Mediterranean world, while several imitations modeled on them were issued within the Persian state. The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) exhausted the silver resources of Athens and eventually destroyed irreparably the Athenian supremacy. With the mines lost and their treasury depleted by the ruinous cost of the Pelloponesian war with Sparta, the Athenians resorted to an emergency issue of plated silver tetradrachms. -

Two Late Fifth Century B.C. Hoards from South Italy

Two late fifth century B.C. Hoards from south Italy Autor(en): Kraay, Colin M. Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Schweizerische numismatische Rundschau = Revue suisse de numismatique = Rivista svizzera di numismatica Band (Jahr): 49 (1970) PDF erstellt am: 08.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-173963 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch COLIN M. KRAAY TWO LATE FIFTH CENTURY B.C. HOARDS FROM SOUTH ITALY Although the first of the hoards here described was found long ago and dispersed immediately after discovery, it still seems possible to extract from the surviving account more detailed information about its contents than has yet been done. -

Ancient Greek Coins

Ancient Greek Coins Notes for teachers • Dolphin shaped coins. Late 6th to 5th century BC. These coins were minted in Olbia on the Black Sea coast of Ukraine. From the 8th century BC Greek cities began establishing colonies around the coast of the Black Sea. The mixture of Greek and native currencies resulted in a curious variety of monetary forms including these bronze dolphin shaped items of currency. • Silver stater. Aegina c 485 – 480 BC This coin shows a turtle symbolising the naval strength of Aegina and a punch mark In Athens a stater was valued at a tetradrachm (4 drachms) • Silver staterAspendus c 380 BC This shows wrestlers on one side and part of a horse and star on the other. The inscription gives the name of a city in Pamphylian. • Small silver half drachm. Heracles wearing a lionskin is shown on the obverse and Zeus seated, holding eagle and sceptre on the reverse. • Silver tetradrachm. Athens 450 – 400 BC. This coin design was very poular and shows the goddess Athena in a helmet and has her sacred bird the Owl and an olive sprig on the reverse. Coin values The Greeks didn’t write a value on their coins. Value was determined by the material the coins were made of and by weight. A gold coin was worth more than a silver coin which was worth more than a bronze one. A heavy coin would buy more than a light one. 12 chalkoi = 1 Obol 6 obols = 1 drachm 100 drachma = 1 mina 60 minas = 1 talent An unskilled worker, like someone who unloaded boats or dug ditches in Athens, would be paid about two obols a day. -

The Coinage of Akragas C

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Studia Numismatica Upsaliensia 6:1 STUDIA NUMISMATICA UPSALIENSIA 6:1 The Coinage of Akragas c. 510–406 BC Text and Plates ULLA WESTERMARK I STUDIA NUMISMATICA UPSALIENSIA Editors: Harald Nilsson, Hendrik Mäkeler and Ragnar Hedlund 1. Uppsala University Coin Cabinet. Anglo-Saxon and later British Coins. By Elsa Lindberger. 2006. 2. Münzkabinett der Universität Uppsala. Deutsche Münzen der Wikingerzeit sowie des hohen und späten Mittelalters. By Peter Berghaus and Hendrik Mäkeler. 2006. 3. Uppsala universitets myntkabinett. Svenska vikingatida och medeltida mynt präglade på fastlandet. By Jonas Rundberg and Kjell Holmberg. 2008. 4. Opus mixtum. Uppsatser kring Uppsala universitets myntkabinett. 2009. 5. ”…achieved nothing worthy of memory”. Coinage and authority in the Roman empire c. AD 260–295. By Ragnar Hedlund. 2008. 6:1–2. The Coinage of Akragas c. 510–406 BC. By Ulla Westermark. 2018 7. Musik på medaljer, mynt och jetonger i Nils Uno Fornanders samling. By Eva Wiséhn. 2015. 8. Erik Wallers samling av medicinhistoriska medaljer. By Harald Nilsson. 2013. © Ulla Westermark, 2018 Database right Uppsala University ISSN 1652-7232 ISBN 978-91-513-0269-0 urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-345876 (http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-345876) Typeset in Times New Roman by Elin Klingstedt and Magnus Wijk, Uppsala Printed in Sweden on acid-free paper by DanagårdLiTHO AB, Ödeshög 2018 Distributor: Uppsala University Library, Box 510, SE-751 20 Uppsala www.uu.se, [email protected] The publication of this volume has been assisted by generous grants from Uppsala University, Uppsala Sven Svenssons stiftelse för numismatik, Stockholm Gunnar Ekströms stiftelse för numismatisk forskning, Stockholm Faith and Fred Sandstrom, Haverford, PA, USA CONTENTS FOREWORDS ......................................................................................... -

The Aurea Aetas and Octavianic/Augustan Coinage

OMNI N°8 – 10/2014 Book cover: volto della statua di Augusto Togato, su consessione del Ministero dei beni e delle attivitá culturali e del turismo – Soprintendenza Speciale per i Beni Archeologici di Roma 1 www.omni.wikimoneda.com OMNI N°8 – 11/2014 OMNI n°8 Director: Cédric LOPEZ, OMNI Numismatic (France) Deputy Director: Carlos ALAJARÍN CASCALES, OMNI Numismatic (Spain) Editorial board: Jean-Albert CHEVILLON, Independent Scientist (France) Eduardo DARGENT CHAMOT, Universidad de San Martín de Porres (Peru) Georges DEPEYROT, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (France) Jean-Marc DOYEN, Laboratoire Halma-Ipel, UMR 8164, Université de Lille 3 (France) Alejandro LASCANO, Independent Scientist (Spain) Serge LE GALL, Independent Scientist (France) Claudio LOVALLO, Tuttonumismatica.com (Italy) David FRANCES VAÑÓ, Independent Scientist (Spain) Ginés GOMARIZ CEREZO, OMNI Numismatic (Spain) Michel LHERMET, Independent Scientist (France) Jean-Louis MIRMAND, Independent Scientist (France) Pere Pau RIPOLLÈS, Universidad de Valencia (Spain) Ramón RODRÍGUEZ PEREZ, Independent Scientist (Spain) Pablo Rueda RODRÍGUEZ-VILa, Independent Scientist (Spain) Scientific Committee: Luis AMELA VALVERDE, Universidad de Barcelona (Spain) Almudena ARIZA ARMADA, New York University (USA/Madrid Center) Ermanno A. ARSLAN, Università Popolare di Milano (Italy) Gilles BRANSBOURG, Universidad de New-York (USA) Pedro CANO, Universidad de Sevilla (Spain) Alberto CANTO GARCÍA, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (Spain) Francisco CEBREIRO ARES, Universidade de Santiago -

The Mysterious World of Celtic Coins

The Mysterious World of Celtic Coins Coins were developed about 650 BC on the western coast of modern Turkey. From there, they quickly spread to the east and the west, and toward the end of the 5th century BC coins reached the Celtic tribes living in central Europe. Initially these tribes did not have much use for the new medium of exchange. They lived self-sufficient and produced everything needed for living themselves. The few things not producible on their homesteads were bartered with itinerant traders. The employ of money, especially of small change, is related to urban culture, where most of the inhabitants earn their living through trade or services. Only people not cultivating their own crop, grapes or flax, but buying bread at the bakery, wine at the tavern and garments at the dressmaker do need money. Because by means of money, work can directly be converted into goods or services. The Celts in central Europe presumably began using money in the course of the 4th century BC, and sometime during the 3rd century BC they started to mint their own coins. In the beginning the Celtic coins were mere imitations of Greek, later also of Roman coins. Soon, however, the Celts started to redesign the original motifs. The initial images were stylized and ornamentalized to such an extent, that the original coins are often hardly recognizable. 1 von 16 www.sunflower.ch Kingdom of Macedon, Alexander III the Great (336-323 BC) in the Name of Philip II, Stater, c. 324 BC, Colophon Denomination: Stater Mint Authority: King Alexander III of Macedon Mint: Colophon Year of Issue: -324 Weight (g): 8.6 Diameter (mm): 19.0 Material: Gold Owner: Sunflower Foundation Through decades of warfare, King Philip II had turned Macedon into the leading power of the Greek world. -

Mildenberg's Dream Collection

Mildenberg's Dream Collection Leo Mildeberg, "From my Dream Collection of Early Greek coins" Some excerpts from a presentation by Leo Mildenberg, Zurich The material stems from auction catalogues and public and private collections. 1 von 57 www.sunflower.ch Leo Mildenberg in his office, May 1999 Dream collection: The collection that I dreamed about is the one I would put together if I were a collector and the prices not so exorbitant. Nevertheless, I can enjoy their beauty by looking at their pictures, be they in black and white or in color." 2 von 57 www.sunflower.ch Sicily, Syracuse, Tetradrachm, c. 410 BC, Arethusa First, a black and white shot by Max Hirmer, Munich. It is an image of Arethusa the Fountain nymph of the city of Syracuse. The die was engraved by Kimon of Syracuse, whose signature is on the hair band on the forehead. Dolphins circle around the head of Arethusa. It is the first great work of art with a facing head, "en face." At the height of Sicilian art between 415 and 400 BC there were only a few artists who could successfully undertake such a challenging task. The coin you see here was made between 406-405 in Syracuse in Sicily under the rule of its powerful King Dionysius I. 3 von 57 www.sunflower.ch Sicily, Syracuse, Tetradrachm, Arethusa The second slide shows the same coin in color, and I like it more, though it is actually a black and white picture that has been colored by hand. Max Hirmer made the photograph during the Second World War for his little book: "Die schönsten Griechenmünzen Siziliens" (The Prettiest Greek Coins of Sicily), which he also wrote. -

Agricultural Practices in Ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman Period

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Hellenic University: IHU Open Access Repository Agricultural practices in ancient Macedonia from the Neolithic to the Roman period Evangelos Kamanatzis SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies January 2018 Thessaloniki – Greece Student Name: Evangelos Kamanatzis SID: 2201150001 Supervisor: Prof. Manolis Manoledakis I hereby declare that the work submitted is mine and that where I have made use of another’s work, I have attributed the source(s) according to the Regulations set in the Student’s Handbook. January 2018 Thessaloniki - Greece Abstract This dissertation was written as part of the MA in Black Sea and Eastern Mediterranean Studies at the International Hellenic University. The aim of this dissertation is to collect as much information as possible on agricultural practices in Macedonia from prehistory to Roman times and examine them within their social and cultural context. Chapter 1 will offer a general introduction to the aims and methodology of this thesis. This chapter will also provide information on the geography, climate and natural resources of ancient Macedonia from prehistoric times. We will them continue with a concise social and cultural history of Macedonia from prehistory to the Roman conquest. This is important in order to achieve a good understanding of all these social and cultural processes that are directly or indirectly related with the exploitation of land and agriculture in Macedonia through time. In chapter 2, we are going to look briefly into the origins of agriculture in Macedonia and then explore the most important types of agricultural products (i.e. -

HOGGARD V. RHODES

Cite as: 594 U. S. ____ (2021) 1 Statement of THOMAS, J. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES ASHLYN HOGGARD v. RON RHODES, ET AL. ON PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT No. 20–1066. Decided July 2, 2021 The petition for a writ of certiorari is denied. Statement of JUSTICE THOMAS respecting the denial of certiorari. As I have noted before, our qualified immunity jurispru- dence stands on shaky ground. Ziglar v. Abbasi, 582 U. S. ___, ___ (2017) (opinion concurring in part and concurring in judgment); Baxter v. Bracey, 590 U. S. ___ (2020) (opinion dissenting from denial of certiorari). Under this Court’s precedent, executive officers who violate federal law are im- mune from money damages suits brought under Rev. Stat. §1979, 42 U. S. C. §1983, unless their conduct violates a “clearly established statutory or constitutional righ[t] of which a reasonable person would have known.” Mullenix v. Luna, 577 U. S. 7, 11 (2015) (per curiam) (internal quota- tion marks omitted). But this test cannot be located in §1983’s text and may have little basis in history. Baxter, 590 U. S., at ___, ___ (slip op., at 2, 4) (opinion of THOMAS, J.). Aside from these problems, the one-size-fits-all doctrine is also an odd fit for many cases because the same test ap- plies to officers who exercise a wide range of responsibilities and functions. Ziglar, 582 U. S., at ___–___ (opinion of THOMAS, J.) (slip op., at 4–5).* This petition illustrates that oddity: Petitioner alleges that university officials violated —————— *Certain Government officials receive heightened immunity, including absolute immunity, based on the common law or their constitutional sta- tus.