Jimmy Cliff by ROB BOWMAN ^■ J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

M.Sc. RESEARCH THESIS LARGE-SCALE MUSIC

LARGE-SCALE MUSIC CLASSIFICATION USING AN APPROXIMATE k-NN CLASSIFIER Haukur Pálmason Master of Science Computer Science January 2011 School of Computer Science Reykjavík University M.Sc. RESEARCH THESIS ISSN 1670-8539 Large-Scale Music Classification using an Approximate k-NN Classifier by Haukur Pálmason Research thesis submitted to the School of Computer Science at Reykjavík University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Computer Science January 2011 Research Thesis Committee: Dr. Björn Þór Jónsson, Supervisor Associate Professor, Reykjavík University, Iceland Dr. Laurent Amsaleg Research Scientist, IRISA-CNRS, France Dr. Yngvi Björnsson Associate Professor, Reykjavík University, Iceland Copyright Haukur Pálmason January 2011 Large-Scale Music Classification using an Approximate k-NN Classifier Haukur Pálmason January 2011 Abstract Content based music classification typically uses low-level feature vectors of high-dimensionality to represent each song. Since most classification meth- ods used in the literature do not scale well, the number of such feature vec- tors is usually reduced in order to save computational time. Approximate k-NN classification, on the other hand, is very efficient and copes better with scale than other methods. It can therefore be applied to more feature vec- tors within a given time limit, potentially resulting in better quality. In this thesis, we first demonstrate the effectiveness and efficiency of approximate k-NN classification through a traditional genre classification task, achieving very respectable accuracy in a matter of minutes. We then apply the approx- imate k-NN classifier to a large-scale collection of more than thirty thousand songs. We show that, through an iterative process, the classification con- verges relatively quickly to a stable state. -

Music: Music and Me (Part 1) Hi Everyone! We Are Going to Be Exploring Our Identity Through Music

Music: Music and Me (Part 1) Hi everyone! We are going to be exploring our identity through music. Our identity is made up of all the different things that make us who we are. Each one of us is completely unique with our own experiences, feelings, family background and dreams. Music is a brilliant way of exploring and expressing our identity. It gives up confidence, power and purpose. Our gender is also a really important part of our identity. For different reasons, there haven’t been enough women working in the music industry. This is completely unjust, and meant that many women weren’t given a fair chance. People all around the world have been working really hard to change this, and we’re starting to see the results. We are going to look at 4 talented female musicians who are exploring their own musical and cultural identity. You will hear how they got to where they are, and see how you can do the same. You can be part of the change. How exciting! We will invite you to try out some different ways of making your own music and to explore some of the most inspirational and influential women in music from the last 100 years. Now don’t worry if you’ve never created your own music before; just enjoy the experience, and have fun! For today’s music lesson, let’s meet the 4 artists. When you listen to each song, write down your personal answers to the following questions (the more detailed your answers, the better): 1. -

100 Amazing Facts About the Negro

The USCA4Truth Behind Appeal: '40 Acres 18-4794and a Mule' | African Doc: American 50-1 History Blog Filed: | The African03/23/2020 Americans: Many Pg: Rivers 1 of to 13 Cross This website is no longer actively maintained Some material and features may be unavailable HOME VIDEO HISTORY YOUR STORIES CLASSROOM PARTNER CONTENT ABOUT SHOP CONNECT WITH PROF. GATES! 100 Amazing Facts About the Negro The Truth Behind ’40 Acres and a Mule’ by Henry Louis Gates, Jr. | Originally posted on The Root We’ve all heard the story of the “40 acres and a mule” promise to former slaves. It’s a staple of black history lessons, and it’s the name of Spike Lee’s film company. The promise was the first systematic attempt to provide a form of reparations to newly freed slaves, and it wasNo. astonishingly 18-4794, radical viewedfor its time, 3/04/2020 proto-socialist in its implications. In fact, such a policy would be radical in any country today: the federal government’s massive confiscation of private property — some 400,000 acres — formerly owned by Confederate land owners, and its methodical redistribution to former black slaves. What most of us haven’t heard is that the idea really was generated by black leaders themselves. It is difficult to stress adequately how revolutionary this idea was: As the historian Eric Foner puts it in his book, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863- 1877, “Here in coastal South Carolina and Georgia, the prospect beckoned of a transformation of Southern society more radical even than the end of slavery.” Try -

Wavelength (December 1981)

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 12-1981 Wavelength (December 1981) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (December 1981) 14 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/14 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ML I .~jq Lc. Coli. Easy Christmas Shopping Send a year's worth of New Orleans music. to your friends. Send $10 for each subscription to Wavelength, P.O. Box 15667, New Orleans, LA 10115 ·--------------------------------------------------r-----------------------------------------------------· Name ___ Name Address Address City, State, Zip ___ City, State, Zip ---- Gift From Gift From ISSUE NO. 14 • DECEMBER 1981 SONYA JBL "I'm not sure, but I'm almost positive, that all music came from New Orleans. " meets West to bring you the Ernie K-Doe, 1979 East best in high-fideUty reproduction. Features What's Old? What's New ..... 12 Vinyl Junkie . ............... 13 Inflation In Music Business ..... 14 Reggae .............. .. ...... 15 New New Orleans Releases ..... 17 Jed Palmer .................. 2 3 A Night At Jed's ............. 25 Mr. Google Eyes . ............. 26 Toots . ..................... 35 AFO ....................... 37 Wavelength Band Guide . ...... 39 Columns Letters ............. ....... .. 7 Top20 ....................... 9 December ................ ... 11 Books ...................... 47 Rare Record ........... ...... 48 Jazz ....... .... ............. 49 Reviews ..................... 51 Classifieds ................... 61 Last Page ................... 62 Cover illustration by Skip Bolen. Publlsller, Patrick Berry. Editor, Connie Atkinson. -

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs

Rolling Stone Magazine's Top 500 Songs No. Interpret Title Year of release 1. Bob Dylan Like a Rolling Stone 1961 2. The Rolling Stones Satisfaction 1965 3. John Lennon Imagine 1971 4. Marvin Gaye What’s Going on 1971 5. Aretha Franklin Respect 1967 6. The Beach Boys Good Vibrations 1966 7. Chuck Berry Johnny B. Goode 1958 8. The Beatles Hey Jude 1968 9. Nirvana Smells Like Teen Spirit 1991 10. Ray Charles What'd I Say (part 1&2) 1959 11. The Who My Generation 1965 12. Sam Cooke A Change is Gonna Come 1964 13. The Beatles Yesterday 1965 14. Bob Dylan Blowin' in the Wind 1963 15. The Clash London Calling 1980 16. The Beatles I Want zo Hold Your Hand 1963 17. Jimmy Hendrix Purple Haze 1967 18. Chuck Berry Maybellene 1955 19. Elvis Presley Hound Dog 1956 20. The Beatles Let It Be 1970 21. Bruce Springsteen Born to Run 1975 22. The Ronettes Be My Baby 1963 23. The Beatles In my Life 1965 24. The Impressions People Get Ready 1965 25. The Beach Boys God Only Knows 1966 26. The Beatles A day in a life 1967 27. Derek and the Dominos Layla 1970 28. Otis Redding Sitting on the Dock of the Bay 1968 29. The Beatles Help 1965 30. Johnny Cash I Walk the Line 1956 31. Led Zeppelin Stairway to Heaven 1971 32. The Rolling Stones Sympathy for the Devil 1968 33. Tina Turner River Deep - Mountain High 1966 34. The Righteous Brothers You've Lost that Lovin' Feelin' 1964 35. -

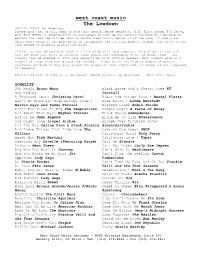

The Lowdown Songlist

west coast music The Lowdown SPECIAL DANCES for Weddings: Please note that we will need to have your special dance requests, (I.E. First Dance, F/D Dance, etc) FOUR WEEKS in advance prior to your event so that we can confirm the band will be able to perform the song and will be able to locate sheet music, mp3 or CD of the song. If some cases where sheet music is not printed or an arrangement for the full band is needed, this gives us the time needed to properly prepare the music. Clients are not obligated to send in a list of general song requests. Many of our clients ask that the band just react to whatever their guests are responding to on the dance floor. Our clients that do provide us with song requests do so in varying degrees. Most clients give us a handful of songs they want played and avoided. If you desire the highest degree of control (allowing the band to only play within the margin of songs requested), we would ask for a minimum 80 requests. Please feel free to call us at the office should you have any questions. – West Coast Music SONGLIST: 24K Magic Bruno Mars Black Horse And A Cherry Tree KT 90s Medley Tunstall A Thousand Years Christina Perri Bless the Broken Road – Rascal Flatts Ain’t No Mountain High Enough (Duet) Blue Bayou – Linda Ronstadt Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Ain’t Too Proud To Beg The Temptations Boogie Oogie A Taste Of Honey All About That Bass Meghan Trainor Brick House Commodores All Of Me John Legend Bring Me To Life Evanescence All Night Long Lionel Richie Bridge Over Troubled -

Sly & Robbie – Primary Wave Music

SLY & ROBBIE facebook.com/slyandrobbieofficial Imageyoutube.com/channel/UC81I2_8IDUqgCfvizIVLsUA not found or type unknown en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sly_and_Robbie open.spotify.com/artist/6jJG408jz8VayohX86nuTt Sly Dunbar (Lowell Charles Dunbar, 10 May 1952, Kingston, Jamaica, West Indies; drums) and Robbie Shakespeare (b. 27 September 1953, Kingston, Jamaica, West Indies; bass) have probably played on more reggae records than the rest of Jamaica’s many session musicians put together. The pair began working together as a team in 1975 and they quickly became Jamaica’s leading, and most distinctive, rhythm section. They have played on numerous releases, including recordings by U- Roy, Peter Tosh, Bunny Wailer, Culture and Black Uhuru, while Dunbar also made several solo albums, all of which featured Shakespeare. They have constantly sought to push back the boundaries surrounding the music with their consistently inventive work. Dunbar, nicknamed ‘Sly’ in honour of his fondness for Sly And The Family Stone, was an established figure in Skin Flesh And Bones when he met Shakespeare. Dunbar drummed his first session for Lee Perry as one of the Upsetters; the resulting ‘Night Doctor’ was a big hit both in Jamaica and the UK. He next moved to Skin Flesh And Bones, whose variations on the reggae-meets-disco/soul sound brought them a great deal of session work and a residency at Kingston’s Tit For Tat club. Sly was still searching for more, however, and he moved on to another session group in the mid-70s, the Revolutionaries. This move changed the course of reggae music through the group’s work at Joseph ‘Joe Joe’ Hookim’s Channel One Studio and their pioneering rockers sound. -

Heather Augustyn 2610 Dogleg Drive * Chesterton, in 46304 * (219) 926-9729 * (219) 331-8090 Cell * [email protected]

Heather Augustyn 2610 Dogleg Drive * Chesterton, IN 46304 * (219) 926-9729 * (219) 331-8090 cell * [email protected] BOOKS Women in Jamaican Music McFarland, Spring 2020 Operation Jump Up: Jamaica’s Campaign for a National Sound, Half Pint Press, 2018 Alpha Boys School: Cradle of Jamaican Music, Half Pint Press, 2017 Songbirds: Pioneering Women in Jamaican Music, Half Pint Press, 2014 Don Drummond: The Genius and Tragedy of the World’s Greatest Trombonist, McFarland, 2013 Ska: The Rhythm of Liberation, Rowman & Littlefield, 2013 Ska: An Oral History, McFarland, 2010 Reggae from Yaad: Traditional and Emerging Themes in Jamaican Popular Music, ed. Donna P. Hope, “Freedom Sound: Music of Jamaica’s Independence,” Ian Randle Publishers, 2015 Kurt Vonnegut: The Last Interview and Other Conversations, Melville House, 2011 PUBLICATIONS “Rhumba Queens: Sirens of Jamaican Music,” Jamaica Journal, vol. 37. No. 3, Winter, 2019 “Getting Ahead of the Beat,” Downbeat, February 2019 “Derrick Morgan celebrates 60th anniversary as the conqueror of ska,” Wax Poetics, July 2017 Exhibition catalogue for “Jamaica Jamaica!” Philharmonie de Paris Music Museum, April 2017 “The Sons of Empire,” Deambulation Picturale Autour Du Lien, J. Molineris, Villa Tamaris centre d’art 2015 “Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry’s Super Ape,” Wax Poetics, November, 2015 “Don Drummond,” Heart and Soul Paintings, J. Molineris, Villa Tamaris centre d’art, 2012 “Spinning Wheels: The Circular Evolution of Jive, Toasting, and Rap,” Caribbean Quarterly, Spring 2015 “Lonesome No More! Kurt Vonnegut’s -

Outsiders' Music: Progressive Country, Reggae

CHAPTER TWELVE: OUTSIDERS’ MUSIC: PROGRESSIVE COUNTRY, REGGAE, SALSA, PUNK, FUNK, AND RAP, 1970s Chapter Outline I. The Outlaws: Progressive Country Music A. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, mainstream country music was dominated by: 1. the slick Nashville sound, 2. hardcore country (Merle Haggard), and 3. blends of country and pop promoted on AM radio. B. A new generation of country artists was embracing music and attitudes that grew out of the 1960s counterculture; this movement was called progressive country. 1. Inspired by honky-tonk and rockabilly mix of Bakersfield country music, singer-songwriters (Bob Dylan), and country rock (Gram Parsons) 2. Progressive country performers wrote songs that were more intellectual and liberal in outlook than their contemporaries’ songs. 3. Artists were more concerned with testing the limits of the country music tradition than with scoring hits. 4. The movement’s key artists included CHAPTER TWELVE: OUTSIDERS’ MUSIC: PROGRESSIVE COUNTRY, REGGAE, SALSA, PUNK, FUNK, AND RAP, 1970s a) Willie Nelson, b) Kris Kristopherson, c) Tom T. Hall, and d) Townes Van Zandt. 5. These artists were not polished singers by conventional standards, but they wrote distinctive, individualist songs and had compelling voices. 6. They developed a cult following, and progressive country began to inch its way into the mainstream (usually in the form of cover versions). a) “Harper Valley PTA” (1) Original by Tom T. Hall (2) Cover version by Jeannie C. Riley; Number One pop and country (1968) b) “Help Me Make It through the Night” (1) Original by Kris Kristofferson (2) Cover version by Sammi Smith (1971) C. -

Mother and Child Ebook Free Download

MOTHER AND CHILD PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Annie Murray | 400 pages | 17 Oct 2019 | Pan MacMillan | 9781509895403 | English | London, United Kingdom Mother and Child PDF Book Had mother or child just passed away, rejoining the other as death brought them together in the afterlife? Please don't be sad, and please don't cry. At this time, however, toddlers are beginning to realise that they are their own individuals and now have the mobility to test the boundaries that their mothers have set for them. Pat Re: Sibling Rivalry in Children I have two kids, 6 and 2, both of them seem to have a very strange attachement to me, they smell my skin and as they do it they… 3 April Judy's Comet. A face that always smiled. Congratulations 4. Mother and Children , by P. His depiction of Mother Teresa is an ode to the universal motherhood that she embodied and the kindness she bestowed on everyone. If your grandniece or grandnephew has their own children, they would be the first cousins twice removed of your kids. Annette Bening. As a multimedia artist, Eva Rocha has worked in sculpture, performance art, set design and video work, so she considers her materials to be whatever is available to her. More From Ask. My Wife in Art a series of sketches , by M. Grandniece or Grandnephew. In her experience, only a person who goes to see art can know why they seek it out. Those parents are the grandparents of your nieces, nephews, sons and daughters. He received his training from the renowned J. -

Bob Marley Poems

Bob marley poems Continue Adult - Christian - Death - Family - Friendship - Haiku - Hope - Sense of Humor - Love - Nature - Pain - Sad - Spiritual - Teen - Wedding - Marley's Birthday redirects here. For other purposes, see Marley (disambiguation). Jamaican singer-songwriter The HonourableBob MarleyOMMarley performs in 1980BornRobert Nesta Marley (1945- 02-06)February 6, 1945Nine Mile, Mile St. Ann Parish, Colony jamaicaDied11 May 1981 (1981-05-11) (age 36)Miami, Florida, USA Cause of deathMamanoma (skin cancer)Other names Donald Marley Taff Gong Profession Singer Wife (s) Rita Anderson (m. After 1966) Partner (s) Cindy Breakspeare (1977-1978)Children 11 SharonSeddaDavid Siggy StephenRobertRohan Karen StephanieJulianKy-ManiDamian Parent (s) Norval Marley Sedella Booker Relatives Skip Marley (grandson) Nico Marley (grandson) Musical careerGenres Reggae rock Music Instruments Vocals Guitar Drums Years active1962-1981Labels Beverly Studio One JAD Wail'n Soul'm Upsetter Taff Gong Island Associated ActsBob Marley and WailersWebsitebobmarley.com Robert Nesta Marley, OM (February 6, 1945 - May 11, 1981) was Jamaican singer, songwriter and musician. Considered one of the pioneers of reggae, his musical career was marked by a fusion of elements of reggae, ska, and rocksteady, as well as his distinctive vocal and songwriting style. Marley's contribution to music has increased the visibility of Jamaican music around the world and has made him a global figure in popular culture for more than a decade. During his career, Marley became known as the Rastafari icon, and he imbued his music with a sense of spirituality. He is also considered a global symbol of Jamaican music and culture and identity, and has been controversial in his outspoken support for marijuana legalization, while he has also advocated for pan-African. -

Sam Moore BIO for Years Sam Moore Was Best Known for His Work With

Sam Moore BIO For years Sam Moore was best known for his work with the historic soul duo Sam & Dave. The rapid-fire style, built on the call and response of gospel, was fashioned and pioneered by Sam and became the trademark of the duo. Songs like Hold On I’m Coming, I Thank You, When Something Is Wrong With My Baby, Soul Sister, Brown Sugar, Wrap It Up and his monster hit Soul Man catapulted them up both the Pop and R & B Charts. Sam & Dave sold more than 10 million records worldwide. The music and sound of Sam & Dave became so popular that the duo served as the inspiration for The Blues Brothers parody by Dan Aykroyd and John Belushi. Though he has tremendous love and respect for the music he created as “the voice” of the duo, Sam, who has been called “the blast furnace of soul,” has maintained his appeal and his stardom as a solo artist and continues to tour scoring critical acclaim for his work. He recorded Rainy Night In Georgia, as a duet with Conway Twitty, which earned them a platinum record as well as two Country Music Association Awards nominations. This was Twitty’s last recording. The Grammy Award winner has countless television appearances globally including The Leno Show, Late Night With David Letterman, Later With Jools, The Today Show, Entertainment Tonight, The Grammys and many others. Sam has also appeared in several major movies including One Trick Pony, Tapeheads, Blues Brothers 2000 and Night of The Golden Eagle. A documentary filmed by the legendary D.A.