The Every Student Succeeds Act: States Leading the Way

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Silver Elephant Dinner

SOUTH CAROLINA REPUBLICAN PARTY THE ROAD TO THE WHITE HOUSE 53rd ANNUAL SILVER ELEPHANT PRE-RECEPTION SOUTH CAROLINA REPUBLICAN PARTY THE ROAD TO THE WHITE HOUSE 53rd ANNUAL SILVER ELEPHANT GUEST SOUTH CAROLINA REPUBLICAN PARTY THE ROAD TO THE WHITE HOUSE 53rd ANNUAL SILVER ELEPHANT STAFF SOUTH CAROLINA REPUBLICAN PARTY THE ROAD TO THE WHITE HOUSE 53rd ANNUAL SILVER ELEPHANT PRESS SOUTH CAROLINA REPUBLICAN PARTY THE ROAD TO THE WHITE HOUSE 53RD ANNUAL SILVER ELEPHANT DINNER • 2020 FTS-SC-RepParty-2020-SilverElephantProgram.indd 1 9/8/20 9:50 AM never WELCOME CHAIRMAN DREW MCKISSICK Welcome to the 2020 Silver Elephant Gala! For 53 years, South Carolina Republicans have gathered together each year to forget... celebrate our party’s conservative principles, as well as the donors and activists who help promote those principles in our government. While our Party has enjoyed increasing success in the years since our Elephant Club was formed, we always have to remember that no victories are ever perma- nent. They are dependent on our continuing to be faithful to do the fundamen- tals: communicating a clear conservative message that is relevant to voters, identifying and organizing fellow Republicans, and raising the money to make it all possible. As we gather this evening on the anniversary of the tragic terrorists attacks on our homeland in 2001, we’re reminded about what’s at stake in our elections this year - the protection of our families, our homes, our property, our borders and our fundamental values. This year’s election offers us an incredible opportunity to continue to expand our Party. -

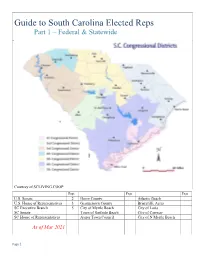

Guide to South Carolina Elected Reps Part 1 – Federal & Statewide

Guide to South Carolina Elected Reps Part 1 – Federal & Statewide Courtesy of SCLIVING.COOP Page Page Page U.S. Senate 2 Horry County Atlantic Beach U.S. House of Representatives 3 Georgetown County Briarcliffe Acres SC Executive Branch 5 City of Myrtle Beach City of Loris SC Senate Town of Surfside Beach City of Conway SC House of Representatives Aynor Town Council City of N Myrtle Beach As of Mar 2021 Page 1 U.S. Senate The Senate is composed of two senators from each state, elected by voters, for six-year terms. U. S. Senate Lindsey Graham [R] South Carolina 4th 6-year ends Jan 2027 290 Russell Senate Office Building Served U.S. Senate since Washington, DC 20510-4001 2003 Phone: (202) 224-5972 Served U.S. House 1995- 2003 McMillan Federal Bldg 401 West Evans St, Suite 111 Committee Assignments: Florence SC 29501 -Appropriations 843-669-1505 -Budget, Ranking Member -Judiciary 530 Johnnie Dodds Blvd, Suite 202 -Environment & Public Mt Pleasant SC 29464 Works 843-849-3887 Website: lgraham.senate.gov Tim Scott [R] U. S. Senate Began Jan 2013; ends Jan 104 Hart Senate Office Building 2023 Washington, DC 20510 South Carolina Served U.S. House 2011- (202) 224-6121 2013 1901 Main St, Suite 1425 Committee Assignments: Columbia, SC 29201 (803) 771-6112x2500 -Finance Committee -Banking, Housing, Urban 2500 City Hall Lane, 3rd Floor Suite Affairs North Charleston, SC 29406 -Health, Education, Labor (843) 727-4525 & Pensions -Small Business & Website: www.scott.senate.gov Entrepreneurship -Special Committee on Aging, Ranking Member Page 2 U.S. -

Journal Senate State of South Carolina

NO. 72 JOURNAL OF THE SENATE OF THE STATE OF SOUTH CAROLINA REGULAR SESSION BEGINNING TUESDAY, JANUARY 8, 2019 _________ MONDAY, MAY 20, 2019 Monday, May 20, 2019 (Statewide Session) Indicates Matter Stricken Indicates New Matter The Senate assembled at 12:00 Noon, the hour to which it stood adjourned, and was called to order by the PRESIDENT. A quorum being present, the proceedings were opened with a devotion by the Chaplain as follows: Psalm 118: 24 “This is the day that the Lord hath made; Let us rejoice and be glad in it.” Let us pray. O Lord, though we now begin an additional session of the Senate, we do so…not with regret, but with praise…for this is the day that You have made for us. Give us a watchful eye and an open mind to Your hand in this hour. May what we say and what we do be in accordance with Your will. Grant, O Lord, that we might look beyond ourselves and make this a special week for the people of South Carolina. In Your holy name we pray, Amen. The PRESIDENT called for Petitions, Memorials, Presentments of Grand Juries and such like papers. Point of Quorum At 12:06 P.M., Senator LEATHERMAN made the point that a quorum was not present. It was ascertained that a quorum was not present. Call of the Senate Senator LEATHERMAN moved that a Call of the Senate be made. The following Senators answered the Call: Bennett Campbell Campsen Cash Climer Corbin Cromer Davis Goldfinch Grooms Hembree Johnson Leatherman Loftis Malloy Martin Massey Matthews, John McElveen Nicholson Peeler Rice Sabb Scott Senn Setzler Shealy Talley Turner Williams [SJ] 1 MONDAY, MAY 20, 2019 Young A quorum being present, the Senate resumed. -

Report of the Education Policy Review and Reform Task Force

Report of the Education Policy Review and Reform Task Force Submitted to the Honorable Jay Lucas Speaker of the House Submitted by the Honorable Rita Allison, Chair January __, 2016 [November 19 Draft] Table of Contents Overview of the Education Policy Review and Reform Task Force p. 2 Description of Task Force Meetings p. 3 Description of Subcommittee Meetings p. 6 Background p. 8 Findings p. 9 Projected Timeline p. 14 Subcommittee Recommendations p. 15 Appendices p. 34 OVERVIEW The Defendants and the Plaintiff Districts must identify the problems facing students in the Plaintiff Districts, and can solve those problems through corporately designing a strategy to address critical concerns and cure the constitutional deficiency evident in this case. Abbeville County School District v. State, 767 S.E. 2d 157, 180 (2014). After the South Carolina Supreme Court issued its long-awaited decision in the case of Abbeville v. South Carolina (Cite), Speaker of the House of Representatives Jay Lucas commissioned the Education Policy Review and Reform Task Force. According to Speaker Lucas,“[e]ffective education reform requires more than just suggestions from administrators; it demands valuable input from our job creators who seek to hire trained and proficient employees. All available avenues should be explored to guarantee our students receive a workforce-ready education that prepares each child for the 21st century.” In order to gain a broad perspective from multiple vantage points, the following individuals were appointed to the Task Force: Representative Merita A. “Rita” Allison (District 36-Spartanburg), Chairwoman of the House Education and Public Works Committee. (Chair of the Task Force) April Allen, Director of State Government Relations, Continental Tire Corporation Wanda L. -

2017 ANNUAL REPORT Improvements Ineducation

Focusing on what matters 2017 ANNUAL REPORT Th e South Carolina Education Oversight Committee (EOC) is an independent, non- partisan group made up of 18 educators, business people, and elected offi cials who have been appointed by the legislature and governor. Th e EOC is charged with encouraging continuous improvement in SC public schools, approving academic content standards and assessments, overseeing the implementation of the state’s educational accountability system, and providing information documenting improvements in education. Providing a Foundation for Learning Report of Publicly funded 4K programs......................................4 Community Block Grant Program..............................................6 Th e Importance of Partnerships in Education Summer Reading Camp Partnership Report...............................8 Martin’s Math Team...................................................................10 Transforming the High School Experience High School Task Force Report ................................................12 A New Day of Education Accountability Accountability System Model Recommendations......................14 contents Dear Friend, I am pleased to once again lead the SC Educa on Oversight Commi ee (EOC) as its chairman, represen ng an agency that is focused on what ma ers in today’s educa on environment – children. The issues the EOC tackles are not easy ones; they are o en controversial and emo onal for many people. Our job is not to please everyone – it is to see to it that an environment exists in our state that promotes high achievement for all students. I am proud to say that the decisions the EOC makes are not made alone; they involve the voices of hundreds of stakeholders. This year alone, the EOC engaged 289 individuals in task forces, focus groups, and commi ees around the state and na on in the accomplishment of its work. -

South Carolina Department of Education 1100 Gervais Street 1429 Senate Street Columbia, SC 29201 Columbia, SC 29201

April 13, 2021 The Honorable Henry McMaster Superintendent Molly Spearman Governor of South Carolina Department of Education 1100 Gervais Street 1429 Senate Street Columbia, SC 29201 Columbia, SC 29201 Dear Governor McMaster and Superintendent Spearman, As President and CEO of the Southern Education Foundation (SEF), a 154-year-old civil rights and education advocacy organization, I am writing to encourage you to use South Carolina’s share of K-12 relief funding under the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) toward the advancement and improvement of public schools in the state. As you know, South Carolina will receive $2.11 billion in the third iteration of the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund (ESSERF III) from the ARPA to directly support and bolster public education in the state.i Out of this amount, at least $1.9 billion must be distributed to local educational agencies (LEAs), and the state can reserve a maximum of $211 million for its own use. As a part of its total ESSERF III allocation, South Carolina is also receiving over $105 million to specifically address lost instructional time, $21 million to institute and bolster summer enrichment programs, and another $21 million for afterschool programs.ii In addition, South Carolina will receive a share of the $7.2 billion for broadband expansion from the ARPA and $3.9 billion of the $360 billioniii in state and local funding in the ARPA. This historic infusion of federal funding provides new opportunities to update school infrastructure in low-wealth rural and urban school districts, recruit and retain a high-quality teacher workforce, and implement the recommendations included in this letter. -

Directory of Elected Officials

Lexington/Richland District Five 476-8000 Richland County Council Richland County Elected Officials 1020 Dutch Fork Road Fax: 732-8017 4 year terms 4 year terms Ballantine, SC 29002 Council Office: 2020 Hampton St. 576-2060 www.lex5.k12.sc.us Mailing address: P.O. Box 192 Fax 576-2136 The District meets on the 2nd & 4th Monday at 7:00 PM . Auditor: Paul Brawley 576-2600 Columbia SC 29202 Clerk of Court: Jeanette McBride 576-1947 Michelle Onley, Clerk of Council Coroner: Naida Rutherford 576-1799 Nikki Gardner (2022) Secretary 673-2462 Probate Judge: Amy McCullouch 576-1961 richlandcountysc.gov/government/county-council Jan Hammond, Chair (2022) 781-2462 Sheriff: Leon Lott 576-3000 Directory Of Elected County Council meets on the 1st and 3rd Tuesday of Solicitor: Byron E. Gipson 576-1800 Rebecca B. Hines [email protected] Treasurer: David Adams 576-2250 Ken Loveless (11/22) 345-0547 every month at 6:00 PM . Officials Catherine Huddle (2024) [email protected] Richland County Ombudsman 929-6000 Matt Hogan (11/24) [email protected] [email protected] District Offices Richland County School Boards City of Columbia Elected Officials 4 years terns #1 Bill Malinowski (2022) 932-7919 City Hall: 1737 Main St 545-3000 [email protected] Richland District One Mailing Address: P.O. Box 147 Stevenson Administration Bldg. 231-7000 Columbia, SC 29217 #2 Derrek Pugh (2024) 977-4339 [email protected] 1616 Richland St.,. Columbia, SC 29201 www.columbiasc.net ***Meets 2nd /4th Tues., 7:00 PM*** www.richlandone.org -

Regional Directory

2015 Regional Directory Central Midlands Council of Governments 236 Stoneridge Drive Columbia, SC 29210 Phone: (803) 376-5390 Fax: (803) 376-5394 www.cmcog.org Last Updated on March 31, 2015 0 The Regional Directory of Fairfield, Lexington, Newberry and Richland Counties is published by Central Midlands Council of Governments (CMCOG). Address: 236 Stoneridge Drive, Columbia SC 29210 Phone: (803) 376-5390 Fax: (803) 576-5394 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cmcog.org The information contained in this publication is not copyrighted and may be reproduced. CMCOG makes every attempt to verify the accuracy of the information prior to publication. Please report any errors, omissions and/or changes to Central Midlands Council of Governments. Updates to the Regional Directory are made continually as we receive new information. 1 Table of Contents CENTRAL MIDLANDS COUNCIL OF GOVERNMENTS ............................................................................................... 8 Central Midlands Board of Directors ..................................................................................................................... 10 CMCOG Officers & Special Committees ................................................................................................................. 11 S.C. CONSTITUTIONAL OFFICERS................................................................................................................................... 14 U.S. CONGRESSIONAL DELEGATION ............................................................................................................................ -

2016 Regional Directory

2016 Regional Directory Central Midlands Council of Governments 236 Stoneridge Drive Columbia, SC 29210 Phone: (803) 376-5390 Fax: (803) 376-5394 www.cmcog.org Last Updated on August 11, 2016 The Regional Directory of Fairfield, Lexington, Newberry and Richland Counties is published by Central Midlands Council of Governments (CMCOG). Address: 236 Stoneridge Drive, Columbia SC 29210 Phone: (803) 376-5390 Fax: (803) 576-5394 Email: [email protected] Website: www.cmcog.org The information contained in this publication is not copyrighted and may be reproduced. CMCOG makes every attempt to verify the accuracy of the information prior to publication. Please report any errors, omissions and/or changes to Central Midlands Council of Governments. Updates to the Regional Directory are made continually as we receive new information. i Table of Contents CENTRAL MIDLANDS COUNCIL OF GOVERNMENTS ............................................................................................... 1 Central Midlands Board of Directors ....................................................................................................................... 3 CMCOG Officers & Special Committees ................................................................................................................... 4 S.C. CONSTITUTIONAL OFFICERS..................................................................................................................................... 7 U.S. CONGRESSIONAL DELEGATION .............................................................................................................................. -

South Carolina Higher Education Advisory Committee

SOUTH CAROLINA HIGHER EDUCATION ADVISORY COMMITTEE Committee Recommendations April 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS 01 Executive Summary 02 List of Committee Recommendations 03 South Carolina Higher Education Advisory Committee Members 04 Preparing Students for Postsecondary Success Recommendations 05 Supporting Postsecondary Completion for All Students Recommendations 06 Strengthening Career Pathways for Tomorrow’s Workforce Recommendations SOUTH CAROLINA HIGHER EDUCATION ADVISORY COMMITTEE COMMITTEE RECOMMENDATIONS | April 2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Leaders from across South Carolina came together in late 2019 and early 2020 to serve as members of the South Carolina Higher Education Advisory Committee (“Committee”). The Committee discussed six foundational topics and identified a series of action steps for each, which are summarized in the next section and discussed in detail throughout this report. These recommendations will be presented to the South Carolina Commission on Higher Education (CHE), who will then use this work to prioritize goals and develop specific next steps. The Committee was designed to support CHE, led by President and Executive Director Dr. Rusty Monhollon, as it works to ensure that all residents of South Carolina have the support they need to access and succeed in higher education. The Committee evaluated the successes and challenges of South Carolina’s current higher education landscape and identified a number of areas for further growth. CHE partnered with The Hunt Institute and the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association (SHEEO) to identify 34 bipartisan leaders from across South Carolina who represent a diverse range of perspectives – including representatives from the governor’s office, the legislature, the business community, leaders of institutions of higher education (IHEs), students, and professors, among other constituencies (see next page for full list of Committee members). -

Blue Ridge 8-20.Indd

BLUE RIDGE Two August milestones AS I’M PREPARING this month’s its program because we recognize report, it’s been 1,785 days that the folks who work here are our since Blue Ridge Electric greatest asset. It’s therefore incumbent Cooperative employees upon us to design the safest possible www.blueridge.coop recorded their most recent environment in which these individuals lost-time accident. By the time can perform their tasks. FOR ALL YOUR CUSTOMER SERVICE this magazine arrives in your Also essential to a successful safety NEEDS AMANDA MACHEN Call Toll-Free (800) 240-3400 mailbox, five full years will program is employee support. In that have passed since that last respect, our safety record speaks for AUTOMATED OUTAGE REPORTING accident occurred. August 4, 2015 was itself. Our workforce has obviously 1-888-BLUERIDGE the exact date. That represents an almost embraced all aspects of our emphasis on PICKENS unbelievable accomplishment! I have to safe job practices. Consequently, they’ve P.O. Box 277 take my hat off to the entire Blue Ridge reached a milestone that’s truly rare in 734 West Main St. workforce for their impressive focus on the world of work. Pickens, SC 29671 working safely. OCONEE 80th anniversary P.O. Box 329 Quality leadership The month also welcomes another 2328 Sandifer Blvd. This kind of safety performance doesn’t milestone that’s of special significance Highway 123 just happen. For one thing, it’s critical to our Blue Ridge organization. This Westminster, SC 29693 to have quality leadership at the helm August 14th, the co-op will be observing MISSION STATEMENT of any job training and safety program. -

2020 General Election Recap

2020 General Election Recap Federal and State Elections Compiled by: This document serves to educate and give individuals & organizations an opportunity to learn about election results throughout South Carolina. All results reflected in this document are South Carolina specific. Federal Election Results The final day of a historic election with record turnout took place on November 3, 2020. While votes are still being counted in the election for US President, South Carolina’s outlook began taking shape shortly after the polls closed. There were significant increases in early voting as compared to 2016, with both Republicans and Democrats showing up early and pushing South Carolina’s voter turnout to 72.10%. Federal Election Results President & Vice President Donald J Trump Joseph R Biden Mike Pence Kamala Harris South Carolina Results While President Trump won the 9 electoral votes from the State of South Carolina, President-elect Joe Biden won the national election. November 3, 2020: Election day & States appointed their electors States must appoint their electors to the electoral college on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November under a federal law passed by Congress in 1845. December 8, 2020: The safe harbor deadline in the electoral college Six days before the electoral colleges convene to vote is the "safe harbor" deadline. While states aren't legally required to certify their results by this date, if they do so, they can avoid Congress getting involved and resolving a potential dispute over which candidate won a particular state's electoral college votes. December 14, 2020: Electors vote On the second Monday after the second Wednesday in December, slates of electors selected by voters convene in all 50 states and the District of Columbia to formally cast their votes for president and vice president.