11. Representative Judiciary in India an Argument for Gender Diversity In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CIJL Bulletin-7-1981-Eng

CIJL BULLETIN N°7 CONTENTS CASE REPORTS India 1 Paraguay 19 Pakistan 8 Guatemala 24 Malta 13 El Salvador 25 Haiti 17 ACTIVITIES OF LAWYERS ASSOCIATIONS Geneva Meeting on the Independence of Lawyers 27 The Inter-American Bar Association 32 Declaration of All-India Lawyers Conference 35 ARTICLE The Difficult Relationship of the Judiciary with the Executive and Legislative Branches in France by Louis Joinet 37 APPENDIX CIJL Communication to Inter-American Commission on Human Rights Concerning Attacks on Judges and Lawyers in Guatemala 45 CENTRE FOR THE INDEPENDENCE OF JUDGES AND LAWYERS April 1981 Editor: Daniel O'Donnell THE CENTRE FOR THE INDEPENDENCE OF JUDGES AND LAWYERS (CIJL) The Centre for the Independence of Judges and Lawyers was created by the In ternational Commission of Jurists in 1978 to promote the independence of the judiciary and the legal profession. It is supported by contributions from lawyers' organisations and private foundations. The Danish, Netherlands, Norwegian and Swedish bar associations, the Netherlands Association of Jurists and the Association of Arab Jurists have all made contributions of $1,000 or more for the current year, which is greatly appreciated. The work of the Centre during its first two years has been supported by generous grants from the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, but its future will be dependent upon increased funding from the legal profession. A grant from the Ford Foundation has helped to meet the cost of publishing the Bulletin in english, french and spanish. There remains a substantial deficit to be met. We hope that bar associations and other lawyers' organisations concerned with the fate of their colleagues around the world will decide to provide the financial support essential to the survival of the Centre. -

(CIVIL) NO. 558 of 2012 Kalpana Mehta and Ot

1 REPORTABLE IN THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA CIVIL ORIGINAL JURISDICTION WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 558 OF 2012 Kalpana Mehta and others …Petitioner(s) Versus Union of India and others …Respondent(s) WITH WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 921 OF 2013 J U D G M E N T Dipak Misra, CJI. [For himself and A.M. Khanwilkar, J.] I N D E X S. No. Heading Page No. A. Introduction 3 B. The factual background 4 B.1 The Reference 6 C. Contentions of the petitioners 8 D. Contentions of the respondents 12 E. Supremacy of the Constitution 14 F. Constitutional limitations upon the 17 legislature 2 G. Doctrine of separation of powers 21 H. Power of judicial review 28 I. Interpretation of the Constitution – The 34 nature of duty cast upon this Court I.1 Interpretation of fundamental rights 40 I.2 Interpretation of other 42 constitutional provisions J. A perspective on the role of Parliamentary 48 Committees K. International position of Parliamentary 54 Committees K.1 Parliamentary Committees in 54 England K.2 Parliamentary Committees in United 55 States of America K.3 Parliamentary Committees in 58 Canada K.4 Parliamentary Committees in 59 Australia L. Parliamentary Committees in India 60 L.1 Rules of Procedure and Conduct of 65 Business in Lok Sabha M. Parliamentary privilege 71 M.1 Parliamentary privilege under the 72 Indian Constitution M.2 Judicial review of parliamentary 81 proceedings and its privilege N. Reliance on parliamentary proceedings as 91 external aids O. Section 57(4) of the Indian Evidence Act 101 P. -

Judicial Review: a Study in Reference to Contemporary Judicial System in India

[Tripathi *, Vol.4 (Iss.5): May, 2016] ISSN- 2350-0530(O) ISSN- 2394-3629(P) Impact Factor: 2.532 (I2OR) DOI: 10.29121/granthaalayah.v4.i5.2016.2673 Social JUDICIAL REVIEW: A STUDY IN REFERENCE TO CONTEMPORARY JUDICIAL SYSTEM IN INDIA Dr. Rahul Tripathi *1 *1 Assistant Professor, Amity University, Jaipur (Rajasthan), INDIA ABSTRACT Judicial review is the process by which the Courts determine whether or not an administrative decision-maker has acted within the power conferred upon him or her by Parliament. That places the question of statutory construction at the heart of the enquiry. The Supreme Court enjoys a position which entrusts it with the power of reviewing the legislative enactments both of Parliament and the State Legislatures. This grants the court a powerful instrument of judicial review under the constitution. Research reveals that the Supreme Court has taken in hand the task of rewriting the Constitution, which is an important aspect in present scenario. Keywords: Judicial Review, Activism, Writ, Article. Cite This Article: Dr. Rahul Tripathi, “JUDICIAL REVIEW: A STUDY IN REFERENCE TO CONTEMPORARY JUDICIAL SYSTEM IN INDIA” International Journal of Research – Granthaalayah, Vol. 4, No. 5 (2016): 51-55. 1. INTRODUCTION "EQUAL JUSTICE UNDER LAW"-These words reflect the ultimate responsibility of the Judiciary of India. In India, the Supreme Court is the highest tribunal in the Nation for all cases and controversies arising under the Constitution or the laws. As the final arbiter of the law, the Court is charged with ensuring the of Indian people the promise of equal justice under law and, Judicial Review and Judicial Activism: Administrative Perspective & Writs. -

Judiciary of India

Judiciary of India There are various levels of judiciary in India – different types of courts, each with varying powers depending on the tier and jurisdiction bestowed upon them. They form a strict hierarchy of importance, in line with the order of the courts in which they sit, with the Supreme Court of India at the top, followed by High Courts of respective states with district judges sitting in District Courts and Magistrates of Second Class and Civil Judge (Junior Division) at the bottom. Courts hear criminal and civil cases, including disputes between individuals and the government. The Indian judiciary is independent of the executive and legislative branches of government according to the Constitution. Courts- Supreme Court of India On 26 January 1950, the day India’s constitution came into force, the Supreme Court of India was formed in Delhi. The original Constitution of 1950 envisaged a Supreme Court with a Chief Justice and 7 puisne Judges – leaving it to Parliament to increase this number. In the early years, all the Judges of the Supreme Court sit together to hear the cases presented before them. As the work of the Court increased and arrears of cases began to accumulate, Parliament increased the number of Judges from 8 in 1950 to 11 in 1956, 14 in 1960, 18 in 1978 and 26 in 1986. As the number of the Judges has increased, they sit in smaller Benches of two and three – coming together in larger Benches of 5 and more only when required to do so or to settle a difference of opinion or controversy. -

A Constructive Critique of India's Fast-Track Courts

Peterson: Speeding up Sexual Assault Trials: A Constructive Critique of Ind Article Speeding Up Sexual Assault Trials: A Constructive Critique of India's Fast-Track Courts Vandana Petersont India has a strong tradition of judicial activism for social change and comprehensive laws designed to combat sexual violence against women. Yet such crime has significantly escalated. In December 2012, a widely publicized assault occurred in Delhi. The victim's death triggered a frantic response from many quarters including legal scholars, religious leaders, global media, and government officials. The central government undertook a comprehensive review of existing mechanisms to deter future crimes against women. Its findings led to the creation or designation of "fast- track" courts to adjudicatecases involving sexual crime against women. This Article posits that designating "special" courts to hear cases of sexual crime can significantly deter such crime, and implicitly address the social norms which typically motivate such crime. However, the fast-track courts that have been established by the central and state governments of India, with minimal logistical or legislative backing, fall short of making any lasting or normative progress. To that end, this Article suggests best practices from specialized courts in other jurisdictions including specialized domestic violence courts in the United States. Parts I and II describe the contemporary challenges faced by Indian society in the area of sexual violence against women. Parts III and IV describe the history and evolution of fast-track courts and identify areas for improvement. Part V suggests incorporating elements borrowed from t The author is a graduate of Smith College and the University of Michigan Law School. -

Monthly Emagazine "Advocacy"

ADVOCACY TMV's Lokmanya Tilak Law College's MONTHLY eMAGAZINE Volume I Issue 3 (May 2021) CONTENTS 1. Indian Judiciary – Evolution. 2. India’s “Justice League”- Torchbearers of Justice for Modern India. 3. Virtual Courtroom System- Future of India’s Judicial System. 4. Medical Jurisprudence- A Connection between Law and Medicine. 5. Hospital Fires - Laws for Prevention, Protection and Fire Fighting Installations (As per the National Building Code, 2005). Student Editor Faculty In-Charge Purvanshi Prajapat Asst. Prof.Vidhya Shetty BA.LL.B 4th Year Articles invited for the next issue, interested candidates can mail your articles on [email protected] ADVOCACY Volume 1 issue 3 (MAY 2021) FOREWORD World Press Freedom Day I am delighted to share the third issue of our eMagazine known as "ADVOCACY" with all of you, which will provide insights on various legal aspects. In December 1993 the United Nations General Assembly proclaimed that every year worldwide 3rd May would be celebrated as World Press Freedom Day also known as World Press Day. This was done on the recommendations of the UNESCO’s (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cul- tural Organization) General Conference and to mark the anniversary of Windhoek Declaration held in Windhoek, Namibia, from 29 April to 3 May 1991. Every year to mark the significance of this day a Global Conference is organised by UNESCO since 1993 in order to provide an opportunity to the journalists, national authorities, academicians and the general public to discuss about the various changing and challenging aspects of “Freedom of Press.” Also to suggest safety measures to protect the life of the journalists and to work together to identify solutions to the emerging problems or challenges in this arena. -

Ravi Shankar Prasad Hon’Ble Minister for Law & Justice and Electronics and IT Government of India

Lakshman Kadirgamar Memorial Lecture 2017 The Evolution of India’s Constitutional and Democratic Polity by Ravi Shankar Prasad Hon’ble Minister for Law & Justice and Electronics and IT Government of India at Lakshman Kadirgamar Institute of International Relations & Strategic Studies, Colombo, Sri Lanka 15 January 2018 The Evolution of India’s Constitutional and Democratic Polity I am singularly honored today for having been invited to deliver the prestigious Lakshman Kadirgamar Memorial Lecture, held every year in the memory of one of the most outstanding intellectual, jurist and influential diplomat of our times. He was not only a towering figure in Sri Lankan polity but a true south Asian giant. 2. He used his legal training to full effect in his role as Sri Lanka’s per-eminent diplomat, serving twice as the Foreign Minister, when he forged a global consensus against terrorism and violence. He was respected across the globe and had friends all over. 3. Lakshman Kadirgamar was a true friend of India. He believed that a strong India- Sri Lanka relationship, which he described as irreversible excellence, was in the mutual interest of both countries. He enjoyed excellent rapport and confidence of several prominent Indian leaders cutting across party lines, including our former Prime Minister, Shri Atal Bihari Vajpayee. 4. My warm personal regards to Mrs. Suganthie Kadirgamar who was gracious enough to come to New Delhi to personally invite me. I am deeply touched by her extraordinary gesture. II 5. I have consciously chosen the evolution of India’s Democratic and Constitutional Polity as the topic for this memorial lecture today. -

Reform in Indian Judicial System

International Journal of Research in Social Sciences Vol. 7 Issue 8, August 2017, ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Journal Homepage: http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] Double-Blind Peer Reviewed Refereed Open Access International Journal - Included in the International Serial Directories Indexed & Listed at: Ulrich's Periodicals Directory ©, U.S.A., Open J-Gage as well as in Cabell‟s Directories of Publishing Opportunities, U.S.A REFORM IN INDIAN JUDICIAL SYSTEM JP DHANYASREE* INTRODUCTION „JUSTICE DELAYED ID JUSTICE DENIED‟ William Ewart Gladstone It is one of the most quoted lines in the context of Indian Judicial System. The Judiciary of India is an independent body. The judiciary system of India is stratified into various levels. It takes care of maintenance of law and order in the country along with solving problems related to civil and criminal offences. But day by day, due its delayed process losing faith of people to whom it is obliged to provide justice. With increase in rate of pending cases and declination of pronouncement of justice, society considers Justice delayed is Justice denied. This phrase implies that if justice is not carried out really justice because there was a period of time when there was a lack of justice. OBJECTIVES To study about the Indian Judiciary To know the problems faced by the Indian judicial system To suggest reformation of Indian Judicial system RESEARCH METHODOLOGY This research is descriptive and analytical in nature. Secondary and electronic resources have been largely used to gather information and data about the topic. Books, Case laws, Websites and * BA LLB (HONS) SAVEETHA SCHOOL OF LAW, CHENNAI 578 International Journal of Research in Social Sciences http://www.ijmra.us, Email: [email protected] ISSN: 2249-2496 Impact Factor: 7.081 Articles have also been referred. -

F.Y.B.A. Political Paper

31 F.Y.B.A. POLITICALPAPER - I INDIAN POLITICAL SYSTEM © UNIVERSITY OF MUMBAI Dr. Suhas Pednekar Vice-Chancellor University of Mumbai, Mumbai Dr. Kavita Laghate Anil R Bankar Professor cum Director, Associate Prof. of History & Asst. Director & Institure of Distance & Open Learning, Incharge Study Material Section, University of Mumbai, Mumbai IDOL, University of Mumbai Programme Co-ordinator : Anil R. Bankar Associate Prof. of History & Asst. Director IDOL, University of Mumbai, Mumbai-400 098 Course Co-ordinator : Mr. Bhushan R. Thakare Assistant Prof. IDOL, University of Mumbai, Mumbai-400 098 Course Writer : Dr.Ravi Rameshchandra Shukla (Editor) Asst. Prof. & Head, Dept. of Political Science R.D. and S.H. National College and S.W.A. Science College , Bandra (W), Mumbai : Vishakha Patil Asst. Prof. Kelkar Education Trust's V.G.Vaze College of Arts, Science and Commerce, Mithagar Road, Mulund (W), Mumbai : Mr. Roshan Maya Verma Asst. Prof. Habib Educational and Welfare Society's M.S. College of Law : Mr.Aniket Mahendra Rajani Salvi Asst. Prof. Department of Political Science Bhavans College,Andheri (W), Mumbai November 2019, F.Y.B.APOLITICALPAPER - I, Indian Political System Published by : Director Incharge Institute of Distance and Open Learning , University of Mumbai, Vidyanagari, Mumbai - 400 098. DTP Composed : Ashwini Arts Gurukripa Chawl, M.C. Chagla Marg, Bamanwada, Vile Parle (E), Mumbai - 400 099. Printed by : CONTENTS Unit No. Title Page No. 1 Constitution of India 1 2. Citizens and the Constitution 10 3. The Legislature and Judiciary 22 4. The Executive 50 5. Indian FederalSystem 70 6. Partyand PartyPolitics in India 85 7. Social Dynamics 90 8. -

Sociolegally Yours!

SocioLegally Yours ! SocioLegally Yours! Vol. 1, Issue 1 April 2017 Quarterly Magazine Published by Page 1 of 54 Editor-in-Chief’s Note Dear Friends, Greetings from ProBono India ! It gives me immense pleasure to present first issue of SocioLegally Yours !, a quarterly magazine published by ProBono India. Magazine will cover activities of ProBono India, ProBono legal initiatives around the world, articles, case study, important judgements, interview, book review, unknown law, socio-legal photo, cartoon. Other innovative, thought provoking segments are welcome and may be included in upcoming issues. We would be happy to hear from you. Do send your comments/suggestions/views to [email protected] SocioLegally Yours ! Dr. Kalpeshkumar L Gupta Editor in Chief – SocioLegally Yours ! Page 2 of 54 Preface About ProBono India Society and Law both are interlinked area of study. We cannot imagine a society without law/rules/regulations. There are various problems in the society and to handle those situations effectively we need proper laws. Law plays very crucial role in social transformation in any country. Looking at various problems in the society, many laws have been enacted to cope up with the variety of situations. There are various laws but many are not aware about those. To address this situation we need legal awareness activities in the society. On the other side there are some marginalised people who cannot afford to hire a lawyer for legal advice or filing a case. Legal Aid service is needed to serve these kind of people. Many institutions/organizations have been set up which are engaged in various legal aid/awareness activities, some of these activities are highlighted in different way through different mediums but some don’t come into the limelight. -

UGC Research Award in Law 2014.Pdf

National Law University, Delhi Submitted by Sector - 14, Dwarka, New Delhi - 110 078, India Phone : +91 11 2809 4992, Fax : +91 11 2803 4254 Dr Jeet Singh Mann www.nludelhi.ac.in Associate Professor of Law, National Law University Delhi Final Report of the Research Project Under The University Grants Commission Research Award 2012-14 on Impact Analysis of the Legal Aid Services Provided By the Empaneled Legal Practitioners on the Legal Aid System in City of Delhi Submitted by: Dr Jeet Singh Mann Associate Professor of Law, National Law University Delhi Ref. No.: F-30-1/2013 (SA-II) RA-2012-14-GE-DEL-1376 Dated: 17 March 2017 Preface The Right to legal aid services, across the globe, have been recognised an integral part of human rights and fundamental rights. The international instruments and municipal statutory instruments have shaped the Apparatus of legal aid service. The Judiciary have been in the forfront in promoting free legal aid services to poor people, who cannot afford to engage a legal practitioner to protect this interests in courts. Providing right to access to speedy and economical justice for the downtrodden strata of the society is one of the main mandates of such legal aid services. The question that is haunting each one of us is “How far have the services of legal aid efficiently been provided by the legal aid counsels empaneled and whether the beneficiaries of the legal aid services are really satisfied form the quality of services provided by the Legal Aid Counsels (LACs)? The present empirical research on legal aid services delivered by the LACs has been carried out under the University Grants Commission Research Award 201-14. -

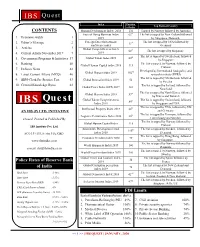

Quest-January-2020

IBS Quest Index Position Top Ranked Country of India CONTENTS Human Development Index -2018 130 Topped by Norway followed by Australia Ease of Doing Business Index 63th The list is topped by New Zealand followed 1. Economic watch 1 2019 by Singapore, Denmark. Foreign Direct Investment The list is topped by USA followed by 2. Editor’s Message 2 11th confidence index Germany 3. Articles 3 Global Competitiveness Index 68th The list is topped by Singapore. 4. Current Affairs November 2019 7 2019 The list is topped by Switzerland, followed Global Talent Index 2019 80th 5. Government Programs & Initiatives 37 by Singapore 6. Ranking 40 The list is topped by Norway, followed by Global Human Capital index 2018 115 Finland 7. Defence News 42 Developed by International food policy and Global Hunger Index 2019 102th 8. Latest Current Affairs (MCQ) 46 research institute (IFPRI) The list is topped by Switzerland, followed 9. IBPS-Clerk Pre Practice Test 53 Global Innovation Index 2019 52 by Sweden 10. General Knowledge Bytes 64 The list is topped by Iceland, followed by Global Peace Index (GPI) 2019 141 Newzland The list is topped by North Korea, followed Global Slavery Index 2018 53th by Eritrea and Burundi Global Talent Competitiveness The list is topped by Switzerland, followed Quest 80th IBS Index 2018 by Singapore and USA The list is topped by USA, followed by UK Intellectual Property Index 2018 44th AN IBS (P) LTD. INITIATIVE and Germany. The list is topped by Germany, followed by Logistics Performance Index 2018 36th Owned, Printed & Published By Luxembourg and Sweden.