Conscription by Capture in the Wa State of Myanmar: Acquaintances, Anonymity, Patronage, and the Rejection of Mutuality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Q&A on Elections in BURMA

Q&A ON ELECTIONS IN BURMA PHOTOGRapHS BY PLATON Q&A ON ELECTIONS IN BuRma INTRODUCTION PHOTOGRapHS BY PLATON Burma will hold multi-party elections on November 7, 2010, the first in 20 years. Some contend the elections could spark a gradual process of democratization and the opening of civil society space in Burma. Human Rights Watch believes that the elections must be seen in the context of the Burmese military government’s carefully manufactured electoral process over many years that is designed to ensure continued military rule, albeit with a civilian façade. The generals’ “Road Map to Disciplined Democracy” has been a path filled with human rights violations: the brutal crackdown on peaceful protesters in 2007, the doubling of the number of political prisoners in Burma since then to more than 2000, the marginalization of WIN MIN, CIVIL RIGHTS LEADER ethnic minority communities in border areas, a rewritten constitution that A medical student at the time, Win undermines rights and guarantees continued military rule, and carefully Min became a leader of the 1988 constructed electoral laws that subtly bar the main opposition candidates. pro-democracy demonstrations in Burma. After years fighting in the jungle, Win Min has become one of the This political repression takes place in an environment that already sharply restricts most articulate intellectuals in exile. freedom of association, assembly, and expression. Burma’s media is tightly controlled Educated at Harvard University, he is by the authorities, and many media outlets trying to report on the elections have been now one of the driving forces behind an innovative collective called the Vahu (in reduced to reporting on official announcements’ and interviews with party leaders: no Burmese: Plural) Development Institute, public opinion or opposition is permitted. -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

Drug Trafficking in and out of the Golden Triangle

Drug trafficking in and out of the Golden Triangle Pierre-Arnaud Chouvy To cite this version: Pierre-Arnaud Chouvy. Drug trafficking in and out of the Golden Triangle. An Atlas of Trafficking in Southeast Asia. The Illegal Trade in Arms, Drugs, People, Counterfeit Goods and Natural Resources in Mainland, IB Tauris, p. 1-32, 2013. hal-01050968 HAL Id: hal-01050968 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01050968 Submitted on 25 Jul 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Atlas of Trafficking in Mainland Southeast Asia Drug trafficking in and out of the Golden Triangle Pierre-Arnaud Chouvy CNRS-Prodig (Maps 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 25, 31) The Golden Triangle is the name given to the area of mainland Southeast Asia where most of the world‟s illicit opium has originated since the early 1950s and until 1990, before Afghanistan‟s opium production surpassed that of Burma. It is located in the highlands of the fan-shaped relief of the Indochinese peninsula, where the international borders of Burma, Laos, and Thailand, run. However, if opium poppy cultivation has taken place in the border region shared by the three countries ever since the mid-nineteenth century, it has largely receded in the 1990s and is now confined to the Kachin and Shan States of northern and northeastern Burma along the borders of China, Laos, and Thailand. -

ITRI High-Level Assessment on OECD Annex II Risks in Wa Territory In

| High-level assessment on OECD risks in Wa territory | May 2015 ITRI High-level assessment on OECD Annex II risks in Wa territory in Myanmar May 2015 v1.0 | High-level assessment on OECD risks in Wa territory | May 2015 Synergy Global Consulting Ltd United Kingdom office: South Africa office: [email protected] Tel: +44 (0)1865 558811 Tel: +27 (0) 11 403 3077 www.synergy-global.net 1a Walton Crescent, Forum II, 4th Floor, Braampark Registered in England and Wales 3755559 Oxford OX1 2JG 33 Hoofd Street Registered in South Africa 2008/017622/07 United Kingdom Braamfontein, 2001, Johannesburg, South Africa Client: ITRI Ltd Report Title: High-level assessment on OECD Annex II risks in Wa territory in Myanmar Version: Version 1.0 Date Issued: 11 May 2015 Prepared by: Quentin Sirven Benjamin Nénot Approved by: Ed O’Keefe Front Cover: Panorama of Tachileik, Shan State, Myanmar. All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of ITRI Ltd. The report should be reproduced only in full, with no part taken out of context without prior permission. The authors believe the information provided is accurate and reliable, but it is furnished without warranty of any kind. ITRI gives no condition, warranty or representation, express or implied, as to the conclusions and recommendations contained in the report, and potential users shall be responsible for determining the suitability of the information to their own circumstances. -

Nam Ngiep 1 Hydropower Project

NAM NGIEP 1 HYDROPOWER PROJECT FINAL DRAFT REPORT 13 AUGUST 2016 A BIODIVERSITY RECONNAISSANCE OF A CANDIDATE OFFSET AREA FOR THE NAM NGIEP 1 HYDROPOWER PROJECT IN THE NAM MOUANE AREA, BOLIKHAMXAY PROVINCE Prepared by: Chanthavy Vongkhamheng1 and J. W. Duckworth2 1. Biodiversity Assessment Team Leader, and 2. Biodiversity Technical Advisor Presented to: The Nam Ngiep 1 Hydropower Company Limited. Vientiane, Lao PDR. 30 June 2016 0 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.................................................................................................................... 6 CONVENTIONS ................................................................................................................................... 7 NON-STANDARD ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ............................................................... 9 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 10 PRINCIPLES OF ASSESSMENT ........................................................................................................ 10 CONCEPTUAL BASIS FOR SELECTING A BIODIVERSITY OFFSET AREA ............................. 12 THE CANDIDATE OFFSET AREA ................................................................................................... 13 METHODS ........................................................................................................................................... 15 i. Village discussions ......................................................................................................................... -

LAO: Greater Mekong Subregion Corridor Towns Development Project

Initial Environmental Examination July 2012 LAO: Greater Mekong Subregion Corridor Towns Development Project Prepared by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment and Savannakhet Provincial Department of Natural Resources for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 1 August 2012) Currency Unit – kip (KN) KN1.00 = $0.00012 $1.00 = KN8,013 ABBREVIATIONS DBTZA – Dansavanh Border Trade Zone Authority DED – detailed engineering design DoF – Department of Forestry DPRA – Development Project Responsible Agency DPWT – District Public Works and Transport Office DNREO – District Natural Resource and Environment Office EA – environmental assessment EIA – environment impact assessment ECA – Environmental Compliance Audit ECC – Environmental Compliance Certificate ECO – Environmental Control Officer EMP – environment monitoring plan EMMU – Environment Management and Monitoring Unit ESD – Environment and Social Division ESIA – Environment and Social Impact Assessment ESO – environmental site officer EA – executing agency EWEC – East-West Economic Corridor FDI – foreign direct investment FGD – focus group discussion FS – Forest Strategy FYSEDP – Five Year Socio Economic Development Plan GDP – gross domestic product GMS – Greater Mekong Subregion GoL – Government of Lao PDR IA – implementing agency IEE – initial environmental examination IUCN – International Union for Conservation of Nature IWRM – Integrated Water Resource Management Lao PDR – Lao People’s Democratic Republic LFA – Land and Forest Allocation LWU – Lao Women Union -

The Cultural Politics of Lao Literature, 1941-1975

INVOKING THE PAST: THE CULTURAL POLITICS OF LAO LITERATURE, 1941-1975 A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Chairat Polmuk May 2014 © 2014 Chairat Polmuk ABSTRACT This thesis examines the role of Lao literature in the formation of Lao national identity from 1945 to 1975. In the early 1940s, Lao literary modernity emerged within the specific politico-cultural context of the geopolitical conflict between French Laos and Thailand. As a result, Lao literature and culture became increasingly politicized in colonial cultural policy to counter Thai expansionist nationalism that sought to incorporate Laos into Thai territorial and cultural space. I argue that Lao literature, which was institutionalized by Franco-Lao cultural campaigns between 1941 and 1945, became instrumental to the invention of Lao tradition and served as a way to construct a cultural boundary between Laos and Thailand. Precolonial Lao literature was revitalized as part of Lao national culture; its content and form were also instrumentalized to distinguish Lao identity from that of the Thai. Lao literature was distinguished by the uses of the Lao language, poetic forms, and classical conventions rooted in what was defined as Laos’s own literary culture. In addition, Lao prose fiction, which was made possible in Laos with the rise of print capitalism and an emergent literate social class, offered another mode of “invented tradition.” Despite its presumed novelty in terms of form and content, early Lao prose fiction was highly conventional in its representation of idealized traditional society in opposition to a problematic modern one. -

Summary Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Nam Theun 2

SUMMARY ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT NAM THEUN 2 HYDROELECTRIC PROJECT IN THE LAO PEOPLE’S DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC November 2004 CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 14 November 2004) Currency Unit – Kip (KN) KN1.00 = $0.000093 $1.00 = KN10,773 ABBREVIATIONS ADB – Asian Development Bank AFD – Agence Française de Développement CIA – cumulative impact assessment EAMP – Environmental Assessment and Management Plan EDL – Electricité du Laos EGAT – Electricity Generating Authority of Thailand EMO – Environmental Management Office EMU – Environmental Management Unit HCC – head construction contractor HCCEMMP – Head Construction Contractor’s Environmental Management and Monitoring Plan HIV/AIDS – human immunodeficiency virus/acute immunodeficiency syndrome IUCN – International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Lao PDR – Lao People’s Democratic Republic MRC – Mekong River Commission NNT – Nakai Nam Theun NPA – national protected area NTFP – nontimber forest product NTPC – Nam Theun 2 Power Company Limited RMU – resettlement management unit ROW – right of way SDP – Social Development Plan SEMFOP – Social and Environment Management Framework and First Operational Plan SESIA – Summary Environmental and Social Impact Assessment SIA – Strategic Impact Assessment STD – sexually transmitted disease STEA – Science, Technology and Environment Agency WMPA – Watershed Management and Protection Authority WEIGHTS AND MEASURES µg – microgram cm – centimeter El – elevation above sea level in meters ha – hectare kg – kilogram km – kilometer km2 – square kilometer kV – kilovolt l – liter m – meter m3 – cubic meter m3/s – cubic meter per second masl – meters above sea level mg – milligram MW – megawatt ºC – degree Celsius NOTES (i) Throughout this report, the Lao words Nam, Xe, and Houay are used to mean “river” and Ban to mean “village”. -

Sold to Be Soldiers the Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in Burma

October 2007 Volume 19, No. 15(C) Sold to be Soldiers The Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers in Burma Map of Burma........................................................................................................... 1 Terminology and Abbreviations................................................................................2 I. Summary...............................................................................................................5 The Government of Burma’s Armed Forces: The Tatmadaw ..................................6 Government Failure to Address Child Recruitment ...............................................9 Non-state Armed Groups....................................................................................11 The Local and International Response ............................................................... 12 II. Recommendations ............................................................................................. 14 To the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC) ........................................ 14 To All Non-state Armed Groups.......................................................................... 17 To the Governments of Thailand, Laos, Bangladesh, India, and China ............... 18 To the Government of Thailand.......................................................................... 18 To the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)....................... 18 To UNICEF ........................................................................................................ -

Kengtung LETTERS by Matthew Z

MZW-5 SOUTHEAST ASIA Matthew Wheeler, most recently a RAND Corporation security and terrorism researcher, is studying relations ICWA among and between nations along the Mekong River. Shan State of Mind: Kengtung LETTERS By Matthew Z. Wheeler APRIL 28, 2003 KENGTUNG, Burma – Until very recently, Burmas’s Shan State was, for me, terra Since 1925 the Institute of incognita. For a long time, even after having seen its verdant hills from the Thai Current World Affairs (the Crane- side of the border, my mental map of Southeast Asia represented Shan State as Rogers Foundation) has provided wheat-colored mountains and the odd Buddhist chedi (temple). I suppose this was long-term fellowships to enable a way of representing a place I thought of as remote, obscure, and beautiful. Be- outstanding young professionals yond that, I’d read somewhere that Kengtung, the principal town of eastern Shan to live outside the United States State, had many temples. and write about international areas and issues. An exempt My efforts to conjure a more detailed picture of Shan State inevitably called operating foundation endowed by forth images associated with the Golden Triangle; black-and-white photographs the late Charles R. Crane, the of hillsides covered by poppy plants, ragged militias escorting mules laden with Institute is also supported by opium bundled in burlap, barefoot rebels in formation before a bamboo flagpole. contributions from like-minded These are popular images of the tri-border area where Burma, Laos and Thailand individuals and foundations. meet as haven for “warlord kingpins” ruling over “heroin empires.” As one Shan observer laments, such images, perpetuated by the media and the tourism indus- try, have reduced Shan State’s opium problem to a “dramatic backdrop, an ‘exotic unknowable.’”1 TRUSTEES Bryn Barnard Perhaps my abridged mental image of Shan State persisted by default, since Joseph Battat my efforts to “fill in” the map produced so little clarity. -

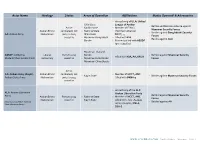

ACLED – Myanmar Conflict Update – Table 1

Actor Name Ideology Status Areas of Operation Affiliations Modus Operandi & Adversaries - Armed wing of ULA: United - Chin State League of Arakan - Battles and Remote violence against Active - Kachin State - Member of FPNCC Myanmar Security Forces Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Rakhine State (Northern Alliance) - Battles against Bangladeshi Security AA: Arakan Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Shan State - NCCT, , , Forces ceasefire - Myanmar-Bangladesh - Allied with KIA - Battles against ALA Border - Formerly allied with ABSDF (pre-ceasefire) - Myanmar-Thailand ABSDF: All Burma Liberal Party to 2015 Border - Battled against Myanmar Security - Allied with KIA, AA, KNLA Students’ Democratic Front democracy ceasefire - Myanmar-India Border Forces - Myanmar-China Border Active AA: Arakan Army (Kayin): Arakan Ethnic combatant; not - Member of NCCT, ANC - Kayin State - Battles against Myanmar Security Forces Arakan State Army Nationalism party to 2015 - Allied with DKBA-5 ceasefire - Armed wing of the ALP: ALA: Arakan Liberation Arakan Liberation Party - Battled against Myanmar Security Army Arakan Ethnic Party to 2015 - Rakhine State - Member of NCCT, ANC Forces Nationalism ceasefire - Kayin State - Allied with AA: Arakan (Also known as RSLP: Rakhine - Battled against AA State Liberation Party) Army (Kayin), KNLA, SSA-S WWW.ACLEDDATA.COM | Conflict Update – Myanmar – Table 1 Rohingya Ethnic Active ARSA: Arakan Rohingya - Rakhine State Nationalism; combatant; not Salvation Army - Myanmar-Bangladesh UNKNOWN - Battles against Myanmar Security -

Sept. 15, 2020 Presentation from the Washington Department of Agriculture

The State of Washington Food & Ag Exports Washington Public Ports Association September 15, 2020 Rianne Perry International Marketing Manager Washington Food & Ag Exports • Pre-COVID Overview: - Top Exports & Markets - Tariff Impacts • US-China Phase I Agreement • COVID-19 Impacts • WSDA Int’l Marketing Program Data Sources: World Trade Atlas/WISER Trade/WA Grain Commission Washington Food & Ag Exports • 2019 WA Food & Ag Exports = $7B • 2019 Total Food & Ag through WA = $15.4B • ~ 30% of all Washington-grown food & ag products are exported • 90% wheat • 60% potatoes • 30% apples • 25% cherries Top WA Food & Ag Exports 2019 Fish & Seafood: $1.1B Top markets: Canada, Japan, China Frozen French Fries: $883M Top markets: Japan, South Korea, Philippines Apples: $732M Image(s) Top markets: Canada, Mexico, Taiwan Wheat: $587M Top markets: Philippines, Japan, South Korea Hay: $518M Top markets: Japan, South Korea, China Top Trading Partners 2019 1) Canada ($1.2B): Seafood, Apples, Cherries 2) Japan ($1B): Wheat, French Fries, Hay 3) China ($462M): Seafood, Hay, French Fries 4) South Korea ($448M): French Fries, Hay, Wheat 5) Mexico ($380M): Apples, Dairy, Pears Tariff Impacts Multiple Retaliatory Tariffs, primarily those imposed by China and India, resulted in trade disruptions for many of Washington’s food and agriculture exporters. Multiple Washington commodities and food products were/remain the targets of retaliatory tariffs beginning in 2018. - Examples: cherries, apples, wine, wheat, hay, dairy, hops - Many targeted multiple times Tariff Impacts Retaliatory Tariffs - Cherries • China was #1 market for WA cherries (2017: $100M) • Original tariff: 10%. • April, 2018: additional 15% • July, 2018: additional 25% • Sept, 2019: additional 5% 2018: exports to China = $67M 2019: exports to China = $60M Tariff Impacts Some China exports have been redirected Exporters had to quickly pivot and expand into other markets.